CARINA VENTER & STEPHANIE VOS

Africa Synthesized: Editorial Note

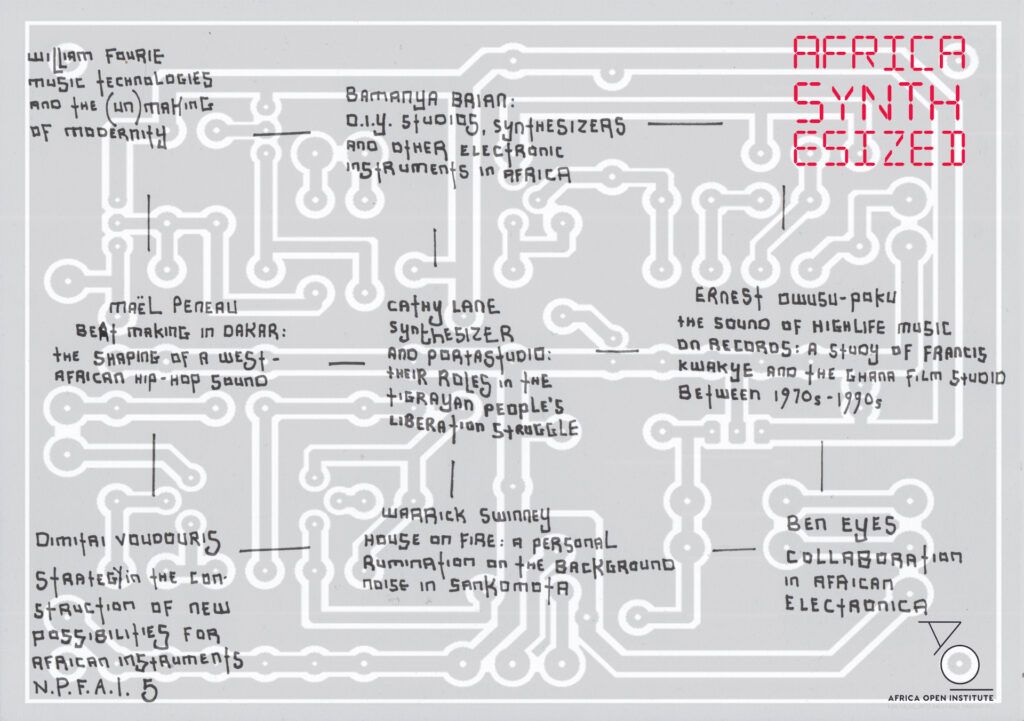

Africa Synthesized is the product of collective curiosity, combined with the imperatives of historical and documentary redress. Collective curiosity, because we knew of pluriverses of instrument builders and recording studios, radio stations and academic sound laboratories, dancefloors, artists, composers and producers, all linked by the sonorities of electronic music and Africa. Historical redress and dissemination because, as conventionally trained academics in the field of music (with conventional here problematically designating ‘Western’), we became aware of institutionalized misrepresentations of histories of electronic music, in which Africa either does not feature at all, is mixed in as an exotic other to energise seemingly Western and American innovations, or is simply displaced by Europe as in the case of the standard narrative of musique concrète. Africa Synthesized is by no means the first to undertake this type of work. Nor does it claim to present anything approaching a systematic survey of electronic music pre-MP3 in/about Africa. Our aims are more modest: to contribute to an existing body of work that document, explore and reimagine electronic music practices in/of Africa.

In the contributions brought together here, Africa figures as a particular geography, marking points of origin for creators, producers, recordings and instruments. But more significantly, Africa names a generative locus of experimental practices, rather than a static object packaging coloniality and control as exoticism fantasised by and for the West. Electronic music is evoked in the broadest possible sense to refer to any type of music or sound that make use of electronic instruments or equipment. The advent of electronic music, not a single moment but a geographically and temporally scattered assemblage of practices, indexes something of the simultaneous and meshed unfoldings of modernity, postmodernity, globalization and political independence.

‘Pre-MP3’ functions as both an historical marker and a designated means of production, meaning that contributions brought together here are not concerned so much with contemporary practices of electronic music than they are with the documentation and reconstruction of historical narratives. The story of electronic music in Africa is invariably also a story of power relations, of the dynamics of creation and self-fashioning, and of formations of new sonic, social and political complexities and solidarities. The MP3 augured a veritable democratization of sound, with the means of sound production and recording and dissemination cheaper and more accessible than before. From the vantage of a post-MP3 world, the economic and logistical barriers to access instruments, sound recording equipment, studios and other means of sound production are easily forgotten.

A tacit theme that runs through contributions drawn together here is the multiplicity of ways that practitioners negotiated these barriers of access. Whereas several practitioners could access radio stations’ and universities’ well-equipped sound laboratories (Halim El-Dabh, Hans Roosenschoon and Jürgen Bräuninger), David Marks was gifted the Woodstock sound system that amplified many multiracial concerts in apartheid South Africa (as well as those of cultural boycott breakers – Editor), and Brian Bamanya and Aragorn Eloff sought out alternative pathways to electronic sound production by building their own instruments.

Several contributions centre around one figure, Halim El-Dabh, mostly (and reductively) remembered for his pioneering tape composition Ta’bir el-Zar (which predates Pierre Schaeffers musique concrète compositions by at least four years). Michael Khoury traces El-Dabh’s life from his roots and early years as an agricultural engineer in Egypt to the United States, where his relationship with the European and North-American avant-garde was a complex one. Kamila Metwaly’s Sonic Letter to el-Dabh quilts together materials from interviews, archives and recordings of his music. Through it, we encounter not only the composer, but a more intimate portrait of personhood. Metwaly offers a trenchant critique of constructions of El-Dabh as originator and ‘father figure of African electronic music’, and challenges the way he is selectively remembered for Ta’bir el-Zar at the expense of his other creative work.

El-Dabh figures in several other contributions. Neo Muyanga cites him as part of an argument that ‘Africa has always been in and of the world in terms of its participation in electronic music’ although its contributions have been obscured by ‘a systematic impulse to exceptionalise western innovation as though… self-generating and self-propelled.’ Muyanga recentres Pan African contributions to electronic music with reference to sample manipulation in hip-hop and the ways synthesizers ‘turned Africa electric’ in the hands of musicians such as Francis Bebey and William Onyeabor. In his reflections on the Unyazi Electronic Music Symposium and Festival of 2005, George E. Lewis remembers El-Dabh who delivered the keynote lecture at this event. Lewis offers a personal patchwork of memory that ventures beyond his recollections of just the festival to friends and networks of connection between South Africa and the United States.

In similarly autobiographical vein, Niklas Zimmer and Cathy Lane offer reflections of their encounters with electronic music in particular contexts: Lane, as a cultural activist assisting the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front to set up portastudios; Zimmer, remembering his encounters with electronic music in particular social, political and personally formative spaces that shaped his own creative practice.

The contributions of Aragorn Eloff, Sazi Dlamini, Lizabé Lambrechts, Warrick Swinney, Maël Péneau and Michael Bhatch all trace particular historical trajectories. Eloff reads and listens through one strain of 20th century electronic music, foregrounding emergence and dynamic possibility (rather than static form captured in sound). With recourse to Deleuze’s idea of the synthesizer as generative of unlimited connections and possibilities, he glosses his own artistic processes as modular synthesizer builder and composer. Remembering his colleague Jürgen Bräuninger, Sazi Dlamini chronicles their collaborations over three decades, sketching a vibrant context and interactions with South African musical practices that informed much of their work at the University of KwaZulu Natal (formerly the University of Natal). Lambrechts uses David Marks’ archive (supplemented with interviews) to follow one sound system as it arrives in apartheid South Africa in the 1970s, and subsequently amplifies and documents fringe spaces of multiracial and commercially unviable music making. Two contributions focus particularly on album productions. Warrick Swinney revisits his collaboration as a newcomer to the Shifty Studio on the recording of Sankomota’s eponymous album, its political context and reception with an attention to the technicalities of production only available to an insider. Maël Péneau’s contribution reconstructs the history of hip hop in Senegal, highlighting that access to means of production and technology shapes the music’s aesthetics. DJ and selector Michael Bhatch’s ‘Sonic Essay’, a playlist of tracks that features synthesizers and other electronic means of production, is drawn from his own record collection, and sets out to ‘engag[e] electronic music in Africa, how it interacts with human bodies on the dance floor, and how these human interactions with electro-sonic experiments, in turn, influence street culture and counter-culture.’ Featuring tracks that do not circulate in the musical mainstream, it both documents marginalised histories and showcases electronic practices.

The ways that electronic technologies are harnessed in artistic practices come to the fore in several creative contributions. Inspired by the techniques used in El Dabh’s early tape music, Shane Cooper’s Tape Collage harnesses (vintage) analogue instruments and recording technologies. In his response to Cooper’s piece, Adam Harper opens a modality of intimate, corporeal listening. Hans Roosenschoon’s Cataclysm (composed in 1980) features even more extensive tape looping techniques with the aid of the technologies of the South African Broadcasting Commission’s studios, where Roosenschoon worked at the time. Stephanus Muller situates Cataclysm inside a South African art music practice that operated within a colonial/apartheid matrix of power and privilege, putting a different spin on what Muyanga notes in his essay ‘Afrotechnolomagic’: that ‘the tools one collects give slant and colour to what a collector is likely to produce, and also transmit an etheric affect and valency that represent the mythos of the collector’s chosen universe as materialised in the performance of a series of “power” actions while in possession of those very tools.’ In creating those very tools for himself, instrument-builder Brian Bamanya shifts this discourse from power to empowerment through his ingenious and inventive DIY approach to instrument building under the alias Afrorack.

Africa Synthesized started out as a physical gathering (conference) scheduled to take place in Stellenbosch on 25-6 June 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic compelled us to find an online means to proceed with the conference, and herri provided an attractive solution: an experimental open access platform unbound by the restrictions of medium and register typical of conventional academic journals. The most obvious gains of this necessitated shift from in-person event to online publication were wider participation and the depositing of a more permanent trace than that left by a physical conference. herri became a conference and proceedings rolled into one. Particularly productive of the online route taken here is the intertextual density enabled by an environment that accommodates hyperlinks and audiovisual materials, and — specific to herri — visual design as curatorial intervention. These all augment the contributions, situating them as nodal points in a network of sounds and narratives.

What would have been orally presented papers or performances, have now largely been rendered in written form (with the exceptions of Maël Péneau, who presents something emblematic of our time – the video of the presentation of a conference paper; Warrick Swinney’s documentary-style video and the sonic reflections contributed by Kamila Metwaly and Cathy Lane). The effect is that conference papers, themselves ‘open’ texts (as Umberto Eco would put it), are here forced into a final product in published form, forfeiting something of the openness of thoughts in progress typical of a conference paper. The decision to migrate to an online journal also created the opportunity to commission a number of contributions in addition to those submitted for the initial conference. The resultant section of herri thus comprises a semi-curated body of work that combines contributions received on the basis of the thematic openness of a call for papers with commissioned contributions.

One of the casualties of the switch from conference to online journal, was the loss of opportunity for real-time interaction. In response to the strange new virtually-mediated world we were plunged in due to COVID-19, and also to somewhat address the loss of real-time interaction, we decided to host a Zoom event on 26 June 2020. The online gathering consisted of two panels – a roundtable on vinyl reissues in Africa, and another for electronic instrument builders to showcase their practices – conceived as conversation starters to stimulate discussion and interaction. Traces of the roundtable on vinyl reissues in Africa appear in Zara Julius’ contribution included here. Julius offers a different account of the Zoom event and takes the discourse further, informed by a critical, decolonial perspective. Her response is an example of the best outcome that a conversation, aimed at opening up discussion with the corollary of diffusion of a central focus, and hamstrung by time limitations with its attendant ramifications for the depth of the conversation, could hope for. The Zoom event concluded with the opinion, shared by the panelists, that we had barely scratched the surface and that important issues were raised for further critical engagement. Julius’ piece crucially addresses this call for further discussion and rigorous critique.

A collection of contributions such as that assembled here necessarily amplifies the gaps and the silences of histories and practices not represented, the voices (particularly of women) not heard, and the work that remains to be done. We are acutely aware of these gaps, and can only hope that Africa Synthesized will provide impetus for continued engagement and documentation.

In drawing this editorial note to a close, we wish to extend thanks to several enablers of Africa Synthesized. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation provided funding under the auspices of the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation, and Stephanus Muller provided advice, support and critical energy in equal measure. Aryan Kaganof was instrumental in procuring and conceptualizing several of the commissioned pieces, and his prompts and prods ensured that we more than kept to deadlines. Willemien Froneman was the conceptual driver of much of this project. Without her intellectual acuity and comradery throughout, Africa Synthesized would never have been.