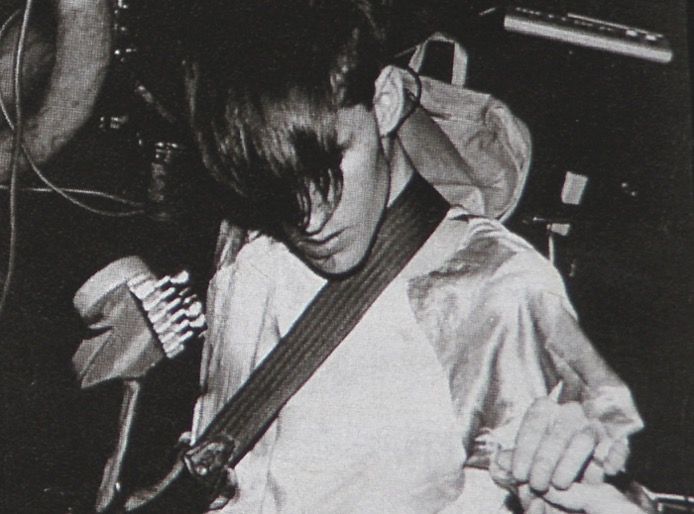

The name Live Jimi Presley, basically derived from two dead icons, comes to the band in a blinding flash as we ponder: how do we get people to come to our gigs? Nobody knows us. Everyone knows about Elvis and Hendrix, even if they’re long departed. Adding ‘Live’ before their names is my idea. Our first gigs are at The Harbour Cafe in Yeoville, the Golden Banana in Berea, Jameson’s and The Doors, which at that stage was in the CBD. We’re still a glam-rock act, with a bit of punk and the odd clang of springs thrown in. We haven’t found our identity yet.

After practice and after gigs, and basically whenever we can, we go out drinking, three or four times a week, mostly in Yeoville, but also in Hillbrow, Braamfontein, Berea and in the central parts of Joburg itself. Rockey Street in Yeoville is open late most nights, and it’s full of people of every colour and creed, mingling freely. To me, this is the new South Africa. You can eat and drink and buy drugs, all friggin’ night. You can even smoke dope while on the jol at The Harbour Cafe, in the courtyard, or up on the roof. There’s bands and plays and flea markets and buskers. And women.

I usually go out with enough money for one beer. After that I cadge drinks off whoever I meet, especially girls. One night I meet a pretty ‘girl’ who I find out later is actually a guy dressed up in drag. ‘She’ is quite attractive, but wants me to buy the drinks. I’m incensed: rock stars don’t buy girls drinks!

The song Kinky Afro epitomises that time for me.

I only went with your mum cos she’s dirty …

To make money, Marc and I, and occasionally Kenny, get ‘extra’ jobs on movies. It’s quite fun at first, and the locations are sometimes odd and interesting. We make R50 a day. Lots of poor and homeless folk are extras, and there’s a kind of bohemian flavour to the work. On top of the 50 bucks, you get a hot meal or two. The worst is if you start smoking in a scene, and it has to be reshot. You have to keep smoking, over and over, for ‘continuity’. It gets nauseating if there are several takes.

There’s a director who asks his crew, ‘Is this artistic? Is this artistic?’ We find this hilarious. The movie crowd believe that they’re all artists, when mostly, they’re just technicians. They do work fucking hard though, and for long hours. They never seem to stop eating: the catering is the most central part of every shoot.

Marc and I get a job fixing guitars. The company that hires us makes such crap guitars that the necks snap, or the bodies split, when customers tighten the strings to tune them up. We have two clamps and some bricks; we buy some horse glue that stinks when it’s heated, stick it hot onto the guitars, put a brick on top till the glue dries. R50 for each fixed guitar: we can do several per day.

I have a brief affair with a buttons addict. Hanging out with Lou and her small circle of fellow addicts is downright weird. They score buttons, smoke them, and promptly pass out. When they awake – which can happen at any time of day or night – they rush around frantically, scrambling to raise cash and score again. This cycle is repeated ad infinitum.

Lou later graduates to spiking pinks[1]Welcanol, a synthetic form of heroin. Users crush up the pink tablets, mix them with water and inject them: their veins became clogged and dies of an overdose. Her mates find her in a toilet, try revive her, give her mouth-to-mouth, to no avail. It’s a fate many in my circle will, in time, come to share.

At our favourite club The Junction I meet a hot girl while snorting coke off a flight of black-and-white chequered stairs. The dude with the coke, I discover, happens to be a wealthy relative of mine. He gives us a lift back to the band house, but the bare, ramshackle house is not to his liking, and he leaves soon after with her in tow. Then I hear a knock; she’s come back. I open the door, and we’re naked in bed soon after. Chica is a stripper. She’s still in her teens, and, I find out, has a toddler whom she supports with her work. Her turntable plays just one or two records, chief among them being the soundtrack to Paris, Texas. We hire a hotel room in Berea, just for kicks, where we have crazy sex; then she insists that I punch her. I’m not into this shit, but eventually, after she keeps insisting, I relent and give her a soft tap in the eye. It’s a move I come to regret: apparently she walks around proudly displaying her shiner, telling the band: ‘Look, Derek hit me!’

She’s seeking a steady relationship, a father for her boy, but I tell her I’m just into having kicks at this stage of my life. Marc offers her his shoulder to cry on, and they end up together soon afterwards, for several years. He’d been having a scene with Tabs, and I strike up one with her, so, in a sense, we ‘swap’ girlfriends. It just happens: none of it is deliberate. Tabs is between homes, and comes to live with the band for a bit, and we end up in bed.

Live Jimi Presley. We’re small-town lads, cocky as hell, and soon brush up against the underbelly of the city, not knowing where danger lurks. A group of us is trying to score buttons when the cops suddenly drive up the street and ask what we’re doing there. Graeme backchats them. A huge cop punches Graeme so hard that he literally leaves the ground and flies for metres. It’s not even a fast punch: there’s just so much weight behind it. In those days, the pigs were pretty paraat[2]the literal translation means ‘ready’, but it really meant they were serious about doing their job properly; these days you can just give them R20 and they fuck off.

One New Year’s eve, the Presleys play a gig at the Black Sun in Yeoville. After the gig I pass out in the car outside. Some band members wake me up in the early hours of morning to pack up our music equipment. I stumble upstairs to fetch my drumkit, totally unaware of what’s happening around me. We find out later that somebody was busy selling coke on the premises, which infuriated the local mafia. They place some heavies at the door and proceed to trash everyone inside.

As I come down the stairs with some drums, one of the mafia dudes rips a tom drum out of my hands and hits me on the head with it. I fall down the stairs, he throws the drum after me, then runs downstairs and leaps onto my face. There’s a clear imprint of the sole of his takkie on my cheek afterwards. A couple of them then proceed to kick the shit out of me. Tabs drags me to safety.

Cash’s eardrum is damaged in the attack, and he decides to sue the mafia for damages. It turns out the guy he’s pressing charges against has about a zillion assault charges against him, so they offer us all bribes to keep our mouths shut. Not wanting to invoke their ire, we agree, and collect the cash from them – in the passage of the magistrates’ court – and we’re able to cover our rent that month.

We’re never certain if the mafia organized the strange assault that follows a few weeks later. I’m busy sleeping at the time (I usually pass out early) when a group of people walk past our house and break the aerial off St Germain’s car. Some of us are sitting on the stoep, and see this open provocation. St Germain runs out with a broken baseball bat to challenge them. They take exception to this, and enter our house in a fury. I awake to shouts, thuds, thundering footsteps and the shattering of glass – pretty terrifying, as I have no idea of what’s going on. I run to the band room and lock myself in it, before whoever is attacking us can get in there and destroy our music equipment. They find a broomstick in the kitchen and break it over St Germain’s head repeatedly, until it’s in tiny pieces. The next day, his head covered in stitches, he goes to buy a gun.

Not long after this, I have an argument with a woman at our favourite club The Junction, deep in the CBD, and decide to walk home, something I often do at the time. In my considerably pissed state, I take a shortcut through a narrow, dimly lit alley, at 3am.

i notice a dude running towards me in a threatening manner, so i turn towards him and put up my fists. but he’s only meant to distract me, and three or four teenage guys leap on me from behind. they drag me into a dark corner, hold my arms, and one begins repeatedly hitting me in the face, while another stabs me in the back with a knife. fortunately I’m wearing a leather jacket and the stabs are shallow – probably intended to make me shut up – but I keep shouting and struggling.

then they get me down on the ground and start putting in the boot, and that’s when I realize that I might not make it out of this alive. somehow I get to my feet and with superhuman strength drag them back towards the street I came off. one of them is grabbing my watch, another has my jacket half off, but i manage to retain both and head towards a couple leaving the club, at which stage my assailants flee. they get nothing from me in the end, but the left side of my face, which I turned into the punches aimed at my nose, looks like a raw burger patty for days.

I manage to track down a friend who works at Radio Pulpit, and we organise to do a recording. It’s a religious station, so we travel to Pretoria late at night, sneaking in a clandestine session. One of the four songs we record comes out particularly well – the only song I did all the lyrics for and composed myself, Assumptions. I wrote it at Rhodes when I found a list of arbitrary words on a piece of paper in the Journ department.

The Presleys are very much a punk, DIY outfit: we design and silkscreen our own posters, then drive around town putting them up ourselves. We buy our steel instruments from scrapyards, cutting them to the right size and sound. Nothing is more anathema than to copy a guitar lick from another band or a known genre; everything we do has to be 100% original. We even have a policy of not practising on our own instruments, in case we fall into known habits: instead, we practise together, almost every night.

Beers and spliffs – or pipes – are obligatory before practice (and gigs), no matter how poor we are. This is supposed to fuel innovation. A classically trained friend tries to jam with us on violin, but is unable to do so without written music. Man, does this reinforce our ethos of not following established formats! When we do write a song, it’s pretty much like nothing anyone else has done, but it does take us ages to write new ones.

One day I’m practising on my own in our band room. I’m standing and jamming on an electric guitar when I place my bare foot on a guitar string that somehow got stuck in a plug. Electricity rushes through my body, cleaves me to the guitar. I open my mouth to scream, but nothing comes out. I know I’m going to die. Luckily I fall over, and off the string.

We’re still pretty much a conventional setup in 1990, with the standard drum kit, bass, guitar and vocals, plus a bit of keyboard and the odd spring here and there. In 1991 we start gradually changing to a more electronic format, incorporating drum machines, synths and samplers, which over the years becomes the distinctive Presley sound. We also change our look from pretty-boy rock band to menacing masks, angle grinders, uniforms and a host of stage props.

For the technically-minded, we start using a Roland TR 505 drum machine, a Korg M1 synthesiser, an Ensoniq TS-10 sequencer, and an Ensoniq ASR-10 sampler. These are linked through the Orchestrator programme on a desktop that runs on Dos 3.1. Everything is connected by and written in MIDI (with no audio). All the instruments are loaded with stiffies, which take about seven minutes to boot. If the system crashes at a gig, we have to leave the stage till it gets back up to speed.

One of our most popular songs, 69 at Half-past 10, derives its name from the settings on our drum machine. The pattern is number 69, and the tempo dial’s set at what would be 10.30 on a clock. The chorus is about the first Bush invasion in the Middle East, in 1991.

We change our lineup. Chris leaves for the UK to pursue a career in sound. He’s replaced by Jimmy, a guy we befriend in a pool hall, who can play guitar properly. Cash gets the axe, a duty that falls upon me: I’m always the axeman. Marc goes back to guitar; Kenny and I share bass duty. At one stage we have a female bassist, a platinum blonde called Serena, but she doesn’t last long.

On a band holiday an octopus attacks Serena while she’s wading in a Mazeppa Bay tidal pool. Our car’s broken, we’re stuck in Mazeppa till it gets repaired, our food supplies were low … so we pounce upon the unfortunate creature, boil and devour it. It’s tough as all hell, despite us beating the flesh with a hammer for ages. Serena and Chica steal gas from the local hotel, roll the cylinder to our house. We scrounge mussels off the rocks at low tide to fill our hungry bellies.

Back in Jozi, we hear that you can get picked up by sugar-daddies and mommies at a certain restaurant in Rosebank, so Serena and I head out there, filled with both hope and trepidation. We find the place, sit down at a table, order a glass of water each. Alas, we’re too poor to even buy tea, and the waiter kicks us out before any rich patrons manage to spot us.

Marc and I try getting into the porn industry. The audition consists of stripping naked, climbing onto the back of a chair and opening your crotch to the camera. I think the object is to see how well-hung you are, how much of an exhibitionist. My knob gets stage fright and shrinks to minimal size. When the porn dudes tell us, ‘we’ll call you’, it doesn’t sound very convincing.

The band, however, is gaining some notoriety. Deon Maas and a mate of his from Tusk Music come and watch us practice. There’s so little space in our rehearsal room that they have to sit on top of the built-in cupboards. They make noises about promoting us, but nothing ever comes of their promises.

Cap’n Spillage opens The 40-Watt Club in the CBD, where he starts hosting raves. It’s pretty cool to take the new drug E and dance out to heavy rave beats. Raves are about dancing all night: there’s no bands. We start to alter the Presley music accordingly, adding more oomph to the drums and bass, making our music more danceable.

One night we go clubbing and notice several of the 40-Watt patrons have blood flowing from their foreheads. We soon find out why: Spillage is handing out balloons filled with laughing gas. You get a lekker rush and kaleidoscope fractal vision … but then pass straight out, and if you’re standing, fall smack on your forehead onto the concrete floor. When I fall over, my beer empties itself in a long trail across the dance-floor. It’s the first thing I see when I wake up.

This smiley mask is really creepy, particularly when used in Our Little Secret, a song about pedophilia

A pretty girl in a pillbox hat picks me at the 40-Watt Club, takes me back to her Yeoville home.

‘You’re probably one of those guys who likes a finger up his arse?’

‘Ooh! Ja …’

A few weeks later she catches me wearing a belt I stole out her cupboard. When she breaks up with me I’m so angry that I throw beer bottles against a wall in her backyard.

I neglect my health while living in Rosettenville: we live on pretty crap food. In conjunction with cigarettes, dagga and acid, my poor eating and sleeping patterns result in several visits to the nearby South Rand Hospital. The band brings me a joint to smoke in hospital, one of the worst highs I ever experience: complete paranoia. Tabs visits me frequently, but I feel quite abandoned by my band mates. It’s a fucking dismal place: all the rejects of society are gathered to die here. A nurse tells me that she wishes motorcyclists didn’t have to wear helmets, shows me a ward full of paralysed men. She says they would be better off if they were dead.

i awake one morning in an incredible amount of pain, in particular, in my face and my hand. i’m also covered in blood. the scariest part is, I have absolutely no recollection of what’s happened, how I came to be in this state. i go to the bathroom to look in the mirror. it’s been shattered at the lower right hand corner. examining my damaged right hand, the cuts appear to match the blow the mirror has been dealt. i conclude it’s me that hit it. the kitchen is a blizzard of destruction. almost every breakable object is shattered, others lay strewn across the floor. the members of my commune slink past and won’t talk to me. eventually Tabs, whose nose is severely swollen, fills me in. we’d been out jolling and had got back late, and the party continued in our kitchen. at some point i’d gotten into an argument, refused to back down, then begun to trash the place. apparently i took a broom to the kitchen crockery. when my friends tried to restrain me, i attempted to trash them too. finally, they had to knock me out.

Whatever the cause, this episode freaks me out: I decide I have to watch my drug consumption, find some work, get a grip on things. It’s a definite turning point. When I feel myself getting drunk at jols, I walk home, sobering up as I go. I get to see a lot of Joburg dawns. Walking becomes a meditation that restores my sanity.

I write to the SADF, tell them that if they call me up for camps, I’ll destroy everything in sight. The call-up letters dry up. My tactic seems to work: I reason that the army is focusing on suckers who toe the line, not the ous who are gonna give them grief. Soon after this conscription and camps end, as South Africa approaches its first democratic election, and the huge, ever-present anxiety of having to evade camps finally lifts from my mind.

I’m still able to cadge money out of my folks when my meagre earnings are insufficient to support me. Addict recovery groups call this enabling. I learn to tug the heartstrings of my mom, especially, and when her heart hardens, my dad. I alternate pushing on their guilt pedals. It works.

When our fridge breaks, I phone a rich relative’s father and plead poverty. He gives me a hundred bucks, and asks me: ‘Do you really think this band thing is going to be forever? What happens when you meet someone, have kids?’ I tell him that I’m 100% sure the band’s going to succeed … but somewhere in the back of my mind, he manages to plant some seeds of doubt.

The Presleys are arrogance personified. There are a couple of bands we play gigs with, like Band of Gypsies and Urban Assault, but we don’t see them as colleagues, or even competition. When Barney Simon lands us a gig at a venue in the CBD and takes too long introducing us, we just start playing over him. Aside from the odd guest artist, we never bother to establish community with anyone else in the music business. Live Jimi Presley was busy creating its own bubble, and we couldn’t see outside of its reflective surface, or we chose not to. But, if you want to be a bunch of artists creating your own unique niche or genre, you have to work damn hard at it, hone your skills to razor sharpness. In retrospect, these first few years in Jozi were possibly the most hectic of my entire life: I was lucky to not end up dead or in an institution.

One day St Germain comes home and tells us he’d found us a new home. It’s a mansion that’s due to be knocked down, but the best part is that it’s in Houghton, where the larneys live. It’s fantastic news: by comparison, the Rosettenville house is a shithole. Our new Houghton home has a massive garden and pool, lots of big rooms, and a double garage in which we can practise to our hearts’ content. Two huge palm trees flank the entrance. Our new home overlooks the M1 highway, but the traffic creates a sort of white noise that hides the racket the band creates on most nights. It’s close to Yeoville and town. We’ve arrived.

Knowing the house is condemned means we can trash it without worrying: we throw shirokens and darts into the doors, scatter tiles when climbing onto the crumbly, leaking roof to fire our guns at dawn (we have a couple by then), allow the carpets to become squelchy-gross. Smashed windows are left broken; unused sections of the garden become overgrown jungle. A massive dagga tree flourishes at the bottom of the plot, which actually survives winter, and produces more heads the following summer.

The Presley mansion quickly earns a reputation as a wild party venue, where bowls of punch are laced with acid and Ecstasy. We buy a pile of beer as tall as us for one party, and vow to return what’s left over to the bottle store, but of course we never do. Quart bottles line the passage from house to studio.

Over the years, a procession of oddballs come to live with us, in any spare space they can find. Rigby, a cyclist dressed in a permanent moonbag and latex shorts, who sometimes sets up discos in our lounge, somehow finds space to live in the cupboard under the stairs. Chica’s parents come to stay. They make amazing vegetarian food, but, when they steal our dope once too often, they get thrown out (literally). An old guy called Jurgen who lives by busking on a flute in Rosebank steals our empties to buy himself wine.

Dawn in Houghton is quite often disrupted by the steely thump of cars smashing into street poles and steel barriers – there’s a corner on the adjacent offramp that drunk drivers just cannot negotiate. If we’re still awake from the previous night’s jol, we investigate the wrecks. South Africans: they know they shouldn’t drive drunk, but they do. A couple of times we see the driver climb out and stagger off, before the cops arrive and test their blood. We filch what’s useful to us from the mangled car remains.

Cash’s wedding is a calamitous affair. Spillage (who’s just cut off a finger for a dare, and thrown it out the window) arrives with a silver Magnum protruding from his waistcoat, dishes out powerful acid to our whole table. One of our mates tries to get into the bride’s mom, then, when the father objects, throws him a punch. We toss our food around the fancy room. I wake up next morning in a gutter at the top of Houghton Hill.

When a festival begins at Rustler’s Valley – a hippie hangout of note – It was famously visited by psychonaut Terence McKenna – and they invite us to play, we leap at the chance. We drive down to the Free State determined to kick ass, but we haven’t counted on one thing: the weather. Just before we’re due to play on the main stage, the heavens open. Dejected, we elect to drop some acid to cheer ourselves up.

Then a move begins to set up a stage in a tent down by the river. The monitors are hauled off the main stage and set up. We’re were invited to play, but the tent is filled with straw, not good for our fire show, and besides, we’re tripping balls by then. So, instead of playing, we get to watch one of the best shows I’ve ever seen, with Gary Herselman’s band Archipelago, Mac Mackenzie’s The Genuines (and Tim Parr’s The Zap Dragons.

Mac steals the show with his Goema energy and speed, hammering on notes with one hand upon the bass guitar’s neck while gesturing with the other. I’ve never seen anything like it. Mac tells Marc before the gig he’s going ‘fuck us up’. He’s right: his band is streets ahead of ours.

Live Jimi Presley’s fame and reputation is growing. Our sound is getting harder, more mechanical; we’re starting to incorporate more angle grinders and fire into the show, we wear black uniforms and masks, fill the stage with dummies and props, creating a unique live show. In the double garage we can actually rehearse with this extra stuff. Things get decidedly industrial.

There’s also a gimp, an idea we steal from Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. Volunteers are stripped naked, cling-wrapped, bound in chains and barbed wire to the stage. Sometimes people in the audience punch and kick the gimp, thinking it’s part of the show; the band fires blanks and grinds sparks into his face. We inject the gimp with ‘gimp juice’ before shows. They have no idea what we’re putting into their veins. (It’s harmless Vitamin B)

The gimp, a literal representation of victim consciousness, adds flavour to the bizarre Presley performances

Strangely, there is never a shortage of folk who want to be abused. We advertise for gimps before shows, then pick the most outrageous-looking character. Fans are proud to be the gimp. Bowie is, over time, our most consistent, reliable gimp; he gets to participate in quite a few shows and accompanies us on several tours. We start doing a lot of tours, and, within a few years, build up a sizeable following in Durban and Cape Town. Our first gig in Durban is the Archiball, where some lout throws a full beer can into Marc’s forehead. Spillage retaliates by throwing steel spring sticks into the audience; we end up running for the door.

We also play at The Playhouse in Durbs, a gig that Lloyd Ross from Shifty Records records; he hands us the cassette as we leave the gig. It’s a midday gig; the audience – many of them aged – are seated, and watch us snarl and spit through songs like Nick Cave’s Junkyard. Years later a fan comments that he’ll never forget us concluding our show by sawing the head off a dummy and drop-kicking it into the dumbstruck crowd.

Within a few years we’re packing out The Purple Turtle in Cape Town and The Station in Durbs, and start demanding R5 000 per gig: a lot of money in those days. We also want additional sweeteners: crates of beer, food, drugs and decent accommodation. It’s the closest I’ve come to being a rock star.

We drive round the Cape peninsula at dawn, firing guns at street signs, terrifying cyclists: wtf were they doing up so early, in such ridiculous attire?

Angle-grinders and scrap metal create a factory ambience onstage

Live performances are planned down to the last detail. We don’t just practise songs: we rehearse the entire set. If I’m playing bass in one song and then going to hit some scrap metal in the next, I need to plan my route, so I don’t collide with another band member who’s also changing instruments. There’s a lot of fire-breathing and petrol on stage, smoke, strobes, sparks flying: if we aren’t precise in our movements it can result in serious injury.

In one song, I get to drop all instruments and just dance around beside Marc, singing backing vocals. I wear a massive Rasta wig, toss the dreadlocks around wildly while I jive.

It’s incredibly liberating to perform behind a mask,

or under a dense wig. I lose all my inhibitions. Oscar Wilde said: ‘Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth.’ He was right.

The Presleys do a collaboration with Vusi Mahlasela and Lesego Rampolokeng, called The Moscow Circus, at the Grahamstown Festival. At that stage we have a manager, who’s managing all three acts, so we cobble together a musical review that combines punk/industrial, acoustic ballads and protest poetry. Chica does magical tricks between songs; the powerful blonde Angel wrestles with an angle grinder. Lesego’s music came from another collaboration that he did, with Warrick Sony, so I end up doing (Warrick’s) great basslines from the album End Beginnings.

After a few weeks of intense practise, we drive down to Grahamstown for the festival. The Moscow Circus nearly sets the venue alight one night. The windows and doors of the Power Station – our massive, rustic, isolated venue – are stuffed with hessian to keep in warmth, and this ignites. The audience panics, rushes for the doors. Just in time, the blaze and audience are narrowly brought under control.

A busload of kids arrives one night from way across the country to see the ‘circus’ and have to be turned away. Adults only. One of our songs is about paedophilia; there’s some graphic onstage stuff in this song, where Lesego stuffs a blonde doll’s face into his crotch, while Marc wanks the long nose of his plastic mask.

This will be … our little secret … our little secret …

One of our crew almost loses a hand to a firework. Angel catches her long hair in the angle grinder and rips out a big chunk of hair and scalp. I ruin my favourite boots by warming my feet too close to a fire.

Playing with these guys is a big leap forward. Vusi has this angelic voice that raises the hair on your neck; Lesego raps his visceral, scatalogical poetry; we do our usual hard rock/industrial/punk stuff. Chica and Angel lend theatrical power to our review. Somehow the combination works. It’s hot shit. Lloyd Ross gets some of it down on video. The audience doesn’t quite know how to react: some people tell us it’s the best thing they’ve ever seen, others get up and leave after the first song.

For 10 consecutive shows, the line-up at the Power Station is Jennifer Ferguson, The Moscow Circus, James Phillips’ band The Lurchers and then Lloyd DJ-ing world music, which is pretty much unknown in the early 90s.

Each night, Ferguson goes over her time limit, sparking off disgusting, unrepeatable labels among us for her arrogance and unprofessionalism. Then we play. After our set, the band climbs up into the roof and sits with Rodge the Dodge and Boogie – the guys doing lights – and smoke spliffs and drink beer while looking down on the Lurchers, who are playing complex, hard-hitting jazzy rock. When they finish, we go downstairs and dance to world music.

James is calling the shots. While most people have high hopes about the ‘new’ South Africa, he’s seeing past the hype.

Just when we thought it’s over, we found it’s only just begun

Just when we thought it’s over, we’re still dying like flies underneath the sun

It’s still going crazy just like it’s always done

He dies a couple of years after that festival, and we play at his memorial concert. The line-up is a who’s who of the top bands of the era. Live Jimi Presley is the last act to take the stage. We cover East Rand Blues, a chaotic song off James’ seminal album Wie is Bernoldus Niemand?

We manage to get some recordings done in the next few years, one with Lloyd Ross, and two with Peter Pearlson, probably the top engineers in the country. They’re rushed affairs that last only a night or two. Given the short time frames, the quality is pretty good. We send a couple of our songs in to Radio 5, then keep phoning the station, asking them to play them, which pushes us up the ratings – once up to Number 1. The Presleys get offers from record companies, but the contracts they ask to sign involve us getting a measly 5% of any profits made, which we feel is just totally immoral. What kind of slut signs a contract like that? Thus the band, while it exists has no album, only live shows. It becomes an urban myth.

In 1993/94 the band undergoes more line-up changes. Jimmy leaves and is replaced by Benjamin, who brings in extra skills: welding steel and moaning/howling on didjeridoo. I soon acquire the art of circular breathing, which proves useful when he, too, departs. I purchase a piece of plumbing pipe for R10, cut it to pitch, paint some rings on it: the sound is better than that of most expensive wooden didjs, and the mouthpiece is easier to blow into. It’s a hippie thing to play didj, but we incorporate it into Presley gigs by building tension at the beginning of a song.

One night Martin and I speed down Munroe Drive, a steep, twisting road between Yeoville and Houghton. We’ve been drinking shots, and I egg him on till he loses control and ploughs his BM straight into a stone wall. I hadn’t even put on a safety belt, and hurtle into the dashboard, which crumples. Luckily we’re so drunk that we don’t hurt ourselves; we get out the car, laugh, have a smoke, walk home.

A week or two later he’s encouraged to smash his new BMW into the same spot by the rest of the band, and promptly does so. In both instances, the cars are complete write-offs. When he leaves for the UK his hand is a mess from holding a firework that ignited in it, plus he’s got stitches from a couple of knife wounds, courtesy of our singer.

Tabs and I are hungover. We’re in the East Rand, visiting her folks. A lit cigarette falls to the floor of our moving car. We both stoop to retrieve it, then, when we look up, a taxi’s stopped in front of us. ‘Oh shit!’ is all we have time to say, then Wham! There’s no serious injuries, but a racial incident almost occurs; a group of aggressive Afrikaners pull up when they see two whites facing down a large group of blacks.

Ooh, there’s a new drug in town! A Goth with long black hair is selling it. He comes to Houghton to show us how to smoke crystal meth (nowadays it’s called tik): you put some powder in a light bulb and heat it up, suck on the end where the metal part used to be. A nice rush, followed by days without sleep. What do you do with yourself when you cannot sleep? You buy some more, of course!

Kenny’s an authentic Goth; perhaps he’s part vampire? He sits through the night while we go out jolling, assembling songs on the sequencer and adding samples. It’s a thankless task, but one that becomes increasingly important for the Presleys as we move from acoustic to electronic.

Sparky works in a pizza restaurant in Brixton called Ciro’s. After his waiting shifts, we sometimes go jolling at gay clubs, which are another universe completely. The barmen are often naked; on your way to the loo are darkened rooms where men fuck men they can’t see and have likely never met before. St Germain once wonders by accident into one of these darkrooms, comes out wide-eyed, pretty quickly.

We do a gig with Pops Mohamed, who plays traditional African instruments, at a place called Carfax; a cool combo of ancient and modern. A guy who works at Carfax makes us black, matching uniforms, adding to our quasi-military appearance. Marc wears a smiley-face badge on his upper arm, with blood dripping from it. We play all over Joburg, at parties, universities, clubs and art exhibitions. We even play in the larney suburb Rosebank, where the audience eats food off a naked woman, though to our irritation, they seemed far more interested in her than us …

As the mid-90s approach, certain members of the band start taking really hard drugs – crack and heroin. I still jol with the band quite a lot, and one night, after a gig, a guy we meet on Rockey Street takes us to his flat in Berea to cook up some coke, a process known as freebasing. Smoking freebase, the purest form of crack, results in the most amazing, intense rush – if you can ‘get’ it – the paradox of smoking crack is that often you don’t, which leaves you hanging for a better ‘hit’. Most of the time you’re disappointed, but once you’ve had that rush, you’ll keep trying to get it back. I have no idea how much this drug will fuck my life up, but I do get a foretaste from my very first flirtation with it. When we get back to the Houghton mansion, I upend a basket of keys where’ve I’d carefully stashed my own, but can’t find them. I start ranting and raving, which irritates the band.

‘Yes Derek, someone’s hidden your keys,’ jeers Marc. I throw over the large communal fridge, he rushes towards me. I deck him with a perfect jab; next thing, St Germain has us both on the ground, holding us with one arm each. Marc still has one arm free, however, and hits me repeatedly in the face across St Germain’s chest. Both my arms are immobile and I cannot defend myself. The next day we discover that Kenny had, for reasons unknown, actually taken my keys from the basket.

Live Jimi Presley is hitting a low ceiling. We’re one of the top-earning ‘alternative’ outfits around, but there’s only so many times you can play the same tiny club circuit. Without an album, we’re hamstrung, as major festivals won’t even consider putting you on their bill without one. Many SA acts at this juncture go overseas; if you succeed in making a name in Europe or the USA, you’re taken seriously back home.

But despite all our media coverage, we’re definitely not a commercial act. And if the money ain’t coming in, no matter how good or united a band is, it’s well-nigh impossible to keep going. As Lloyd Ross says in Michael Cross’s brilliant documentary on James Phillips, The Fun’s Not Over: ‘South Africans are famous for murdering bands.’

Journalists who want to interview or photograph us are told to bring a case of Black Label beer, or not bother. We love to pretend that we’re rock stars; perhaps we even believe it ourselves. We get onto a couple of TV shows; on one shoot at a scrap yard, I cut myself with an angle-grinder, spray blood onto the set; the production company pays the doctor’s bill. Our fans dig our TV appearances, but we never get a call from a big booking agent.

Life with very little work, a band that’s going nowhere and a baby with a mom I fight with is tough. I start to get hooked on smack and crack. A young guy films the Presleys, starts hanging out and playing music with us. Leon has great rhythm and tons of infectious energy and ideas; we make videos with him, he gets us gigs, organizes a recording session. I think to myself: this guy, he’s my ideal replacement.

On my last Durban tour, Marc gives me some of the door takings and a couple of band members visit the brothel beneath our hotel rooms. One of the black hookers fancies me, grabs me and hauls me off to her dingy room. Gradually the consumption of crack, which puts you ‘up’ and heroin, which takes you back ‘down’ begin to take its toll certain key members of the band, particularly Marc. Financially, it’s exactly what we don’t need: every cent we earn seems to find its way into the pockets of the Nigies. I’m starting to become a junkie myself. It feels to me that the band isn’t writing any new songs, that Marc has lost his edge, that our format is becoming clichéd. It’s time, I decide, to quit.

It’s real crap to leave the Presleys. I’ve built my life around the band for the last five or six years, and have few alternative career prospects. I tell the band I’m calling it a day, which doesn’t go down well with Marc at all – he won’t speak to me for years. I sell my bass amp and buy a sax. Perhaps there’s another band or job waiting for me up there on the coast. It’s a long shot, but I have to try something. My life feels incredibly stuck.

| 1. | ↑ | Welcanol, a synthetic form of heroin. Users crush up the pink tablets, mix them with water and inject them: their veins became clogged |

| 2. | ↑ | the literal translation means ‘ready’, but it really meant they were serious about doing their job properly |