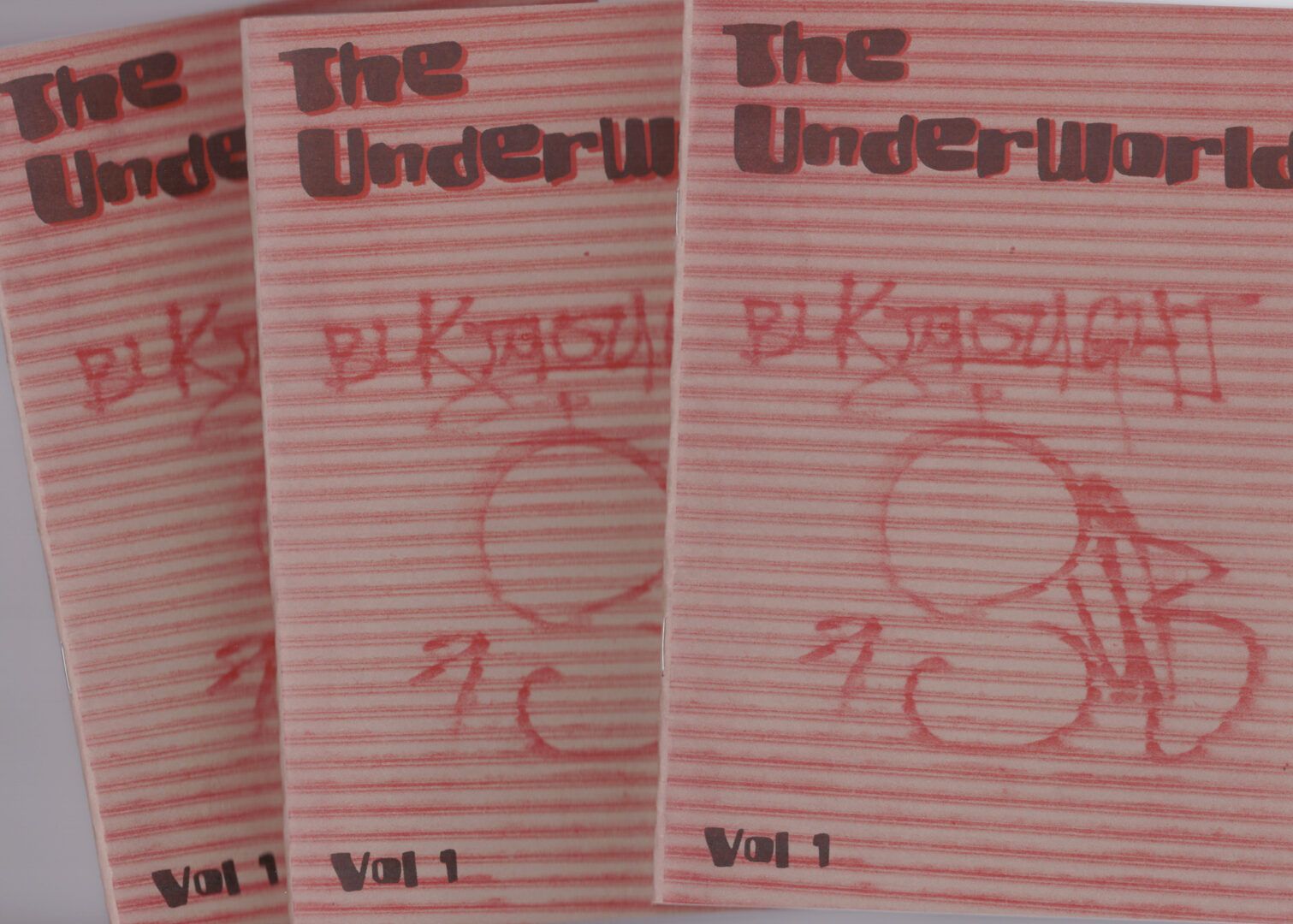

Sometimes readers are attracted or invited to books or other reads for their physical attributes. It might be due to size, the art cover, how the words lay on the pages or the title of the book silently screaming the reader’s name for a pick. The UnderWorld first invited me with its model, a book layered out and printed on a soft cover A5 exercise book like. This, awakening a memory – taking one to the days of being a learner in a township school. In an overcrowded classroom, hearing the loud chattering of myself and other fellow learners suddenly go off. Someone’s exercise book flying from teacher’s desk to the back of the classroom. When the book lands open on the unswept dusty floor to join pieces of paper and Zimba chips plastic packets, the teacher’s voice follows in a tone that refuses to be challenged

“I do not mark naked books”.

The idea of nudity as a result of lack, the book lacking cover, the learner, confronted with the lack of funds to buy the cover. In this case, in order for the book to be assessed by the teacher it needs to dress up, to cover up. Until then the learner cannot participate in the process of knowing how they are progressing with the lessons. Much like the characters in the five stories of Blk Thought Symposium’s literature project: The UnderWorld captures the nucleus that underpins a world where black people exist. In order to be seen, heard or become fair participants in a designed world that does not welcome blackness in its naked form – the characters, are in constant motion, seeking, pleading, finding and settling in alternative ways of survival – of covering up.

Editors, Sive Mqikela and Gabe Morokoe Letshwalo’s pre-text declares that “one concern is common in all these stories, it is the terror of breathing (the clean air of the Almighty God) under pressure, the terror of breathing underworld. And the common response is: I must live, by all means available to me.”

The UnderWorld is birthed by an art collective Blk Thought Symposium. The collective’s beginnings date from seven years ago when students at Wits University gathered outside a lecture hall every Friday afternoon “forming a universe in and outside Wits University, a university beyond redemption” writes its members in an article Imbamba, our kind of song. They read “this or that in Law, History, Literature, Sociology, Musicology and Philosophy, all driven by the need to dialogue, searching for things, for modes and methods of speaking”. The collective continues to speak in song (via their band Blk Thought Music) and in 2018 released volume 1 of The UnderWorld comprising of stories by Isaac Ntuli, Spinach Green and Pitja Thabo.

Each story adds to the project’s accumulated result of revealing what lies in the world under, or underneath the ‘new South Africa’ that is so desperate to convince us of its ‘free-ness and fair-ness’. The stories are occupied with the paintings of existing binaries in South Africa: the black/white, light/dark, us/them, rich/poor, the visible/invisible and those that sit below/above.

The collection opens with the story, The Known Identity Unknown by Isaac Ntuli. The story’s power is in its ability to lend the reader the eyes, ears, feelings, skin and voice of a hobo living in the streets of Johannesburg. The invitation to embody this figure allows one to see themselves in and out of them. That they are not body frames roaming and begging in the city, they are people.

We learn the realities of living in the street and what it means and feels when the rain falls – “sometimes the raindrops are as thick as soya beans” writes Ntuli. The writer’s images are vivid, Ntuli grabs us by the hand and places us at the robots where the man begs for money every day. We see the university bus that passes by, we see “the ladies with clean hands kneading their gears”.

As the story moves, we are reminded that we all have names, engaging with the reader, the character says, “I know you are waiting for my name” as the story concludes he leaves us with a sentence missing his name “my name is…” and this can be easily filled with the reader’s name. Ultimately, at the end we learn that this member of The UnderWorld wants to be seen, for a reasonable person to say “Hi”. To start to see them is knowing who they are and often knowing someone’s name is the starting point of acknowledging their existence. Maybe as a reader, inserting your own name on that last sentence is acknowledging that this man is you.

In the story Unpublic School by the same writer, the cry for existence – to be seen, continues. Here we are introduced to a university student Radiphoso – whose name loosely translates as ‘person of mistakes’. His mistakes begin after meeting his classmates who speak in a “nonblack accent”. Radiphoso goes to work towards erasing his “Tugela high school” English accent that he carried with him to the university. The story takes us back to the idea of covering one’s ‘blackness’ in order to fit in or rather to survive in a world that, by design, automatically kicks you out for being a member of The UnderWorld. Radiphoso sharpens and polishes his tongue to drag words and release them in a way that certainly removes him from being a student whose foundations are from a township school where a “black accent” is a norm and does not place you as a misfit. Whether for Radiphoso this was to fit in or be cool with the girls, this is a story about the complexities of language, how through the English language, black people stand a chance to claim visibility and take on space at the expense of shaving their black selves in the back pocket to hide it – an unfortunate reality.

In the story Red Couch by Spinach Green, we encounter a similar thread, where the identifications and limitations of the English language are explored through a conversation held by three friends on a Friday afternoon discussing the word ‘disintegrate’ and who it is associated with. In its simplicity, one that is not boastful of its critical subject, the story also gets one to pause and reflect on the wildness and busyness of the week due to the pressures of maintaining a living in a capitalist system. The story’s opening “it is a Friday, the busiest afternoon of the week. Traffic will jam, an hour before the sky darkens. Pedestrians will bump, one against another. Biker will move around the small spaces…” displays why the group of friends choose to order pizza, attempt to compose a new music piece and talk about their love interest in their shared shoddy apartment with a red couch. The writer employs something I find interesting with the form of the story – placing characters in a position of exchanging directly. The dialogue between the characters is the essence that builds the story. This works well considering the plot of the story – young people chilling on a Friday afternoon, conversing.

The last two stories by Pitja Thabo A dream and A walk before the sunrise reel us deep into the underworld, unlike in the other stories where there is interfacing or exchanges of the two worlds – one that is black and the other that is not.

A Dream travels all the way from pre-1994 to around 2010. The protagonist rose with excitement early in the morning from his uncomfortable bed covered with a thin mattress that barely protected him when he slept. He wakes to follow a dream which was once held by his mother before her passing. A dream of approval, approval of a shelter – an RDP house that will not only shelter the bodies of his family members but a heart that has experienced coldness due to the wait. Moving in his journey, we encounter other people – the people walking in the darkness of the AMs missioning to work. We get to hear conversations, at the taxi point where elders talk about their murdered faith on the counsellor and the ruling party. We hear about the living and dying dreams of the people which to some have been their only inheritance from their deceased parents and partners handed over from apartheid to democracy.

However, concerns sit with the becoming of the story, as a reader, I would like to be elevated, not only by the story’s subject matter but the literary element that builds a story. How language can be intentionally broken, and be fixed. How words can form a certain kind of rhythm. How punctuation can form a rap beat and inspire me to read the words out loud like I have an audience, jamming alongside the beat with gangster signs in the air. How sentences can punch one straight to despair and pull you back up.

In an article ‘How not to talk about African fiction’ Nigerian writer, Ainehi Edoro suggests we should not talk about African stories only as mirrors of their anthropological accounts but that attention should also be placed on their literary attributes. Yes, the writer takes on a courageous standpoint in writing about a black world which maybe is gruesome, however, it is also important that they do not neglect the beauty in the world that they have the power to create through language.

Here, Pitja Thabo puts the story’s political theme on the centre stage but is stingy in terms of allowing the story to be memorable through its artistic performance. A Dream is a powerful piece but the writer’s style sounds like they are being asked to retrace their steps for a statement at the police station. There is a lot of over explaining, telling of the character’s movements and too little showing.

Consider sentences like “the first thing I did was to take out a skiki (a container, usually a plastic bucket used overnight for urinating…” and “Cover your head Tebogo. I am about to bath. I said to my brother when I realised he was not sleeping” and “After bathing, I went outside to see if there were people on the streets because it is generally not safe to walk alone at that time…” . It is sentences like these that strip the story of its already existing beauty and makes it less captivating, less literary.

The second story by Pitja Thabo and the last in the book A walk before sunrise probes into selective xenophobia (where only foreigners living in townships or in areas with a large population of black people are in danger). After being informed that foreigners, who are people he knows, possibly part of his sub-community, are being set on fire and their shops are looted a father takes no chance on his life and his child’s life, instructs his 9 years old daughter to start packing at 3:30am and they mission to Bramley to seek refuge at his brother’s house because “he stays in the suburbs, this kind of violence does not happen there”.

The narrator’s voice is meant to be of a little girl, however, as a reader I find her missing, nothing about her gender is visible in the story. Nothing about her dress, does it have flowers? Does she grab a bald white doll on her way out as she runs with her father carrying bags or plastics. What about the pre-conceived notions of a man traveling with a 9-year-old girl child in the wee hours of the morning. Everything mentioned in the story is a prop meant to contribute something in it and in my opinion, the child’s gender was not necessary here -unless it was an element of appropriation adding to the narrative. Her image and voice is invisible here, the story would do well with no mentions of gender.

All five stories in the book have a good standpoint when touching cultural and political themes, what they do well is inserting the human element amidst the chaos of issues of housing, language, class, xenophobia and race. At their heart, they are ultimately stories about black people – living – surviving – in The UnderWorld. As noted by the editors, the stories are “possibly about you or someone you know, someone you will meet in due time”. Hopefully Volume 2 of this literature project will have additional content, content that also explores form and style and continues to catalogue these stark tales of our Black being.

Photos courtesy of Mzoxolo Vimba