WARRICK SWINNEY

House on Fire: Sankomota and the art of abstraction

A few years ago, Lloyd Ross gave me a hard-drive containing most of the digitised Shifty Records archive. My interest in the chronology of our work together had me heading for the Sankomota album first, partly because I had travelled down to Maseru with him to help with the recording and partly because it was the first Shifty album to be released. It was also the impetus for Lloyd Ross and Ivan Kadey to get the mobile studio up and running as an effective unit. I had just arrived in Johannesburg and thought it a good opportunity to learn how it all worked.

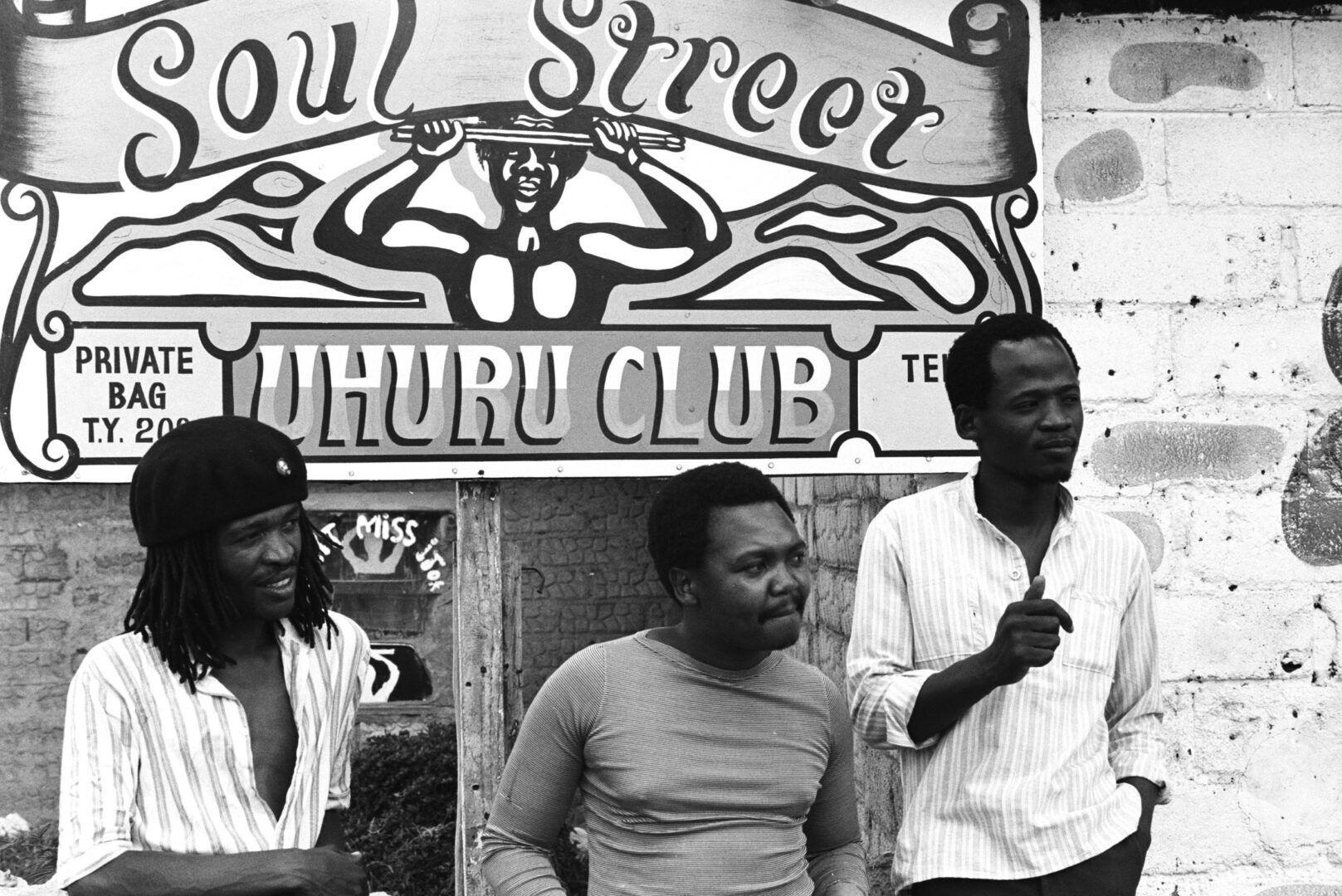

Sankomota were still called UHURU then. They had previously toured South Africa as a larger band but because of their lyric content, their name and the provocative onstage outbursts of a band member who went by the name of Black Jesus, they were all thrown out of South Africa and banned from re-entering.

During a 2004 interview with Alec Khaoli, bass player for the seminal South African afro/funk/rock band Harari, David Coplan (2007) discusses the dangers UHURU were facing from the apartheid authorities: “if you play that music you are going to be taken to John Vorster [Johannesburg Police Headquarters] and never come back,” someone said to them.[1]56 Alec ‘Om’ Khaoli, interview, 5 September 2004 (David Copland.2007. In Township Tonight.Ravan/Jacana.)

So, the idea to take the studio to Lesotho was mooted. In many ways, a perfect first project. Sankomota was a 3-piece Afro-rock band that Ross had seen perform at a hotel in Maseru while he was working on a movie there as a sound recordist. Sadly, every one of them is now deceased, which makes this work more poignant.

The band were:

Frank Leepa on guitar and vocals and who wrote all the material,

Moss Nkofu drums and vocals,

Maruti Selate on bass and vocals,

And for the Maseru sessions Sunshine Moena played keyboards, Sponky Tshabala and myself played percussion.

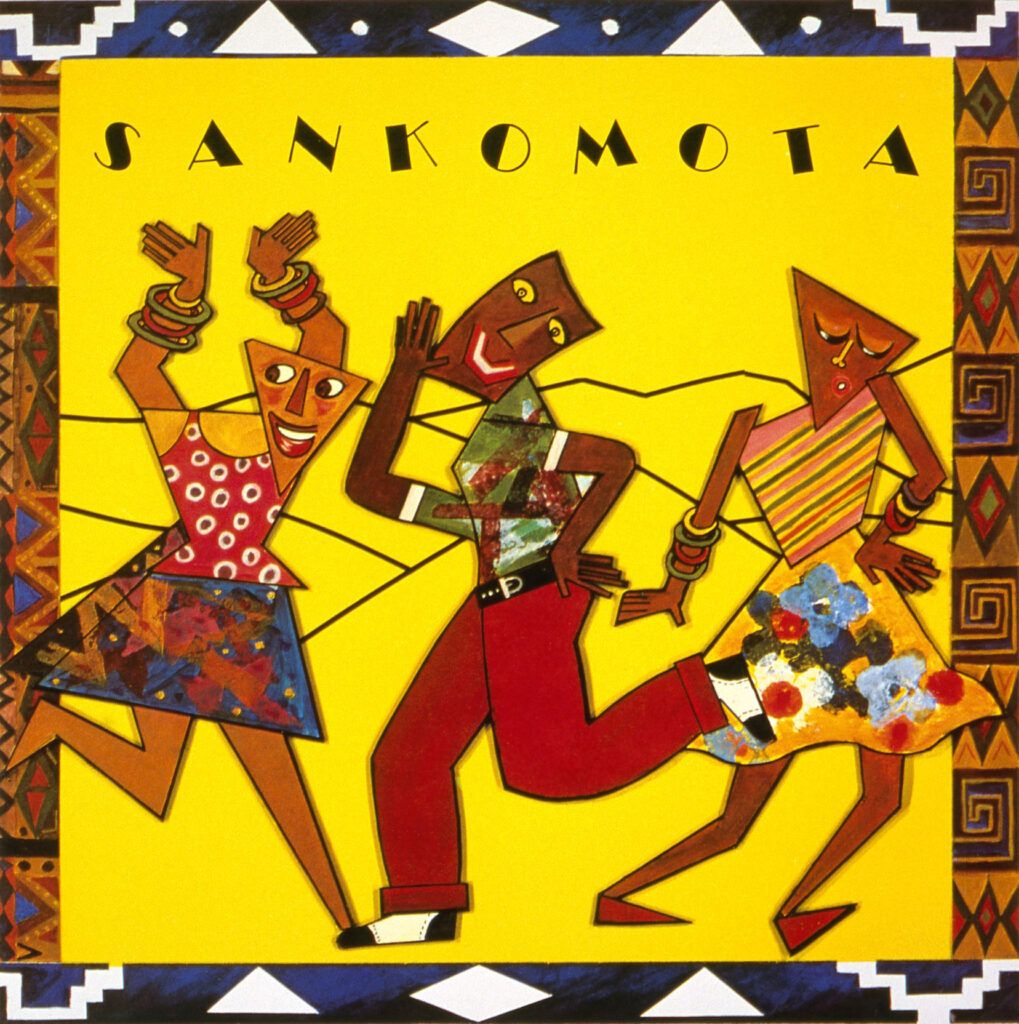

The nine backing tracks for the album were recorded in a few days with a guide vocal track. These were mixed down onto two tracks and the final vocals were then worked on for the rest of the ten day visit. Later in Johannesburg Lloyd employed Rick Van Heerden to write brass arrangements for the album. These were added and the album was mixed and finally released on 11 November 1983.

The original tracks were all recorded onto an Otari reel to reel 8 track tape machine with a Tapco 12 channel mixing desk all set up in the control room of the caravan. A multi cable was run from the caravan into the room of the disused Radio Lesotho building.

I have been curious in revisiting this project as it was my introduction to the Johannesburg music scene and a way to start learning the Studio. I had just moved from Cape Town.

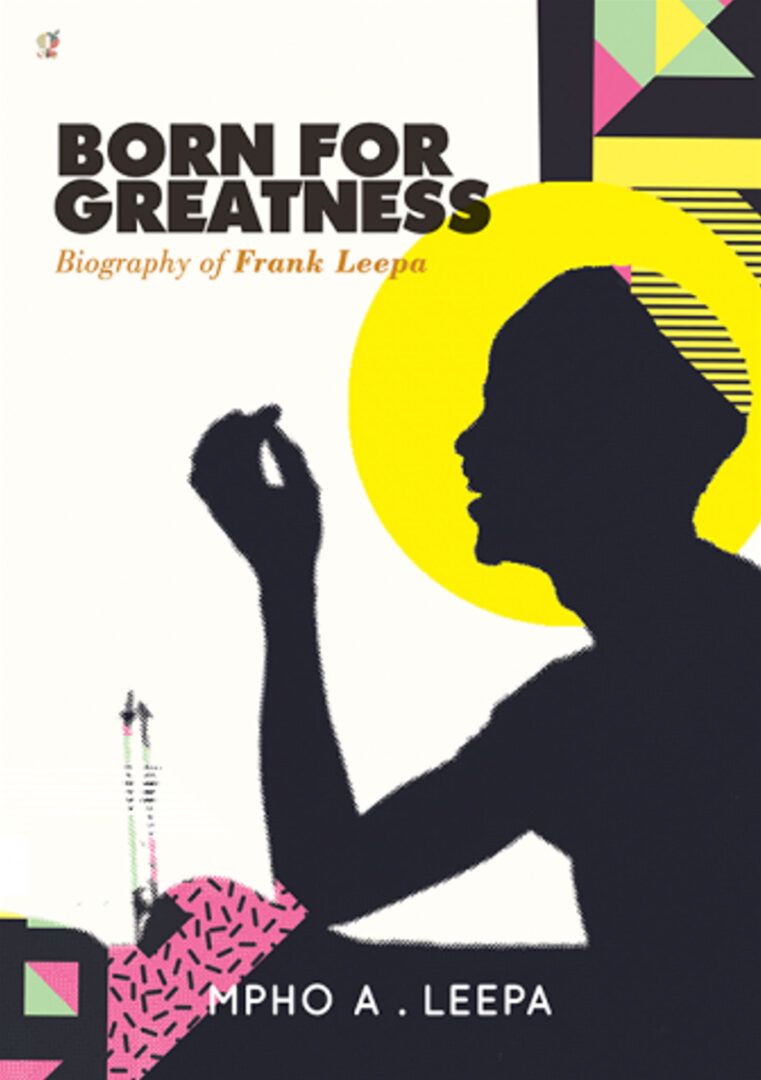

When I was asked to participate in Africa Synthesized I had just read Mpho Leepa’s biographical book on her brother.

Titled Born for Greatness: Biography of Frank Leepa, I was moved by her account of the death of their father – a former high-ranking policeman under Moshoeshoe II. He was hounded and eventually gunned down in the mountains by SADF helicopters working with the illegal Lebua Jonathan government during the 1970 state of emergency. The practice of burning opposing members’ houses saw the family living in terror each time the army marched past.

I decided to first look at the song House on Fire.

Phehello Mofokeng’s reflective essay Ode to Sankomota described House on Fire thus:

House on Fire is a historical reflection of the political situation in Lesotho and why the 1970s and 1980s in Lesotho must never be forgotten by Basotho. The title of the song could have easily been Hearts on Fire – for Basotho’s hearts were on fire during this period. War, violence and tragedy are evoked and the anti-apartheid theme is thick in this song.

Mofokeng, 2018

Later he says:

One of the methods of intimidation was the burning of people’s houses. When Frank Leepa’s father was being hunted down by Lesotho armed forces, they promised to burn his house down to force him to surrender. In the end, they did not, but many other people’s houses were “on fire” – burnt down by the armed forces.

(P93)

I have here the digitised stems of the song as transferred directly from the tape. They are opened up in Protools sound software and come through to this format not without complications, one being noise reduction systems. Using tape meant there was tape hiss measured in a signal to noise ratio – to combat this, noise reduction units were built to encode and decode algorithms. Ross experienced difficulty in finding the correct noise reduction unit to match the one he initially used in the recording. The other problem was finding an 8-track Otari Machine. This transfer was eventually done from a 16-track machine which outputs 2 tracks to represent one.

Another curiosity of mine was the answer Frank gave to a question he was asked by Aryan Kaganof in Amsterdam whilst the band were touring Europe in 1984. Kaganof asked him:

“Are you satisfied with the record? Frank answered that he was not, ‘the mix down, horn section etc. were done in Johannesburg and I was not able to be there. I didn’t write those horn sections they were just added on.’ ”

Kaganof makes the point that if it wasn’t for the record they’d still be playing to the same tiny audience in Maseru.

Another question Kaganof asked Frank Leepa was where the name Sankomota came from:

Sankomota was a warrior during the times of the Moshoeshoe. He was a very brilliant guy, a Pedi. During those times you couldn’t exactly say that this person is a Pedi, this one a Sotho. It was only after the difaquane war that we started having rigid groups called “Pedi” and “Sotho”. Sankomota was important in creating unity amongst the people at the time.

Frank Leepa.1985 interview with Aryan Kaganof, Vula Magazine

They [Shifty] recorded Sankomota’s first album and with this single musical act, history was changed forever. When subjects of Moshoeshoe slumbered that night, they did not know the proportions of history that were made that day (P. Mofokeng, 2018)[2]Mofekeng.P.2018. Sankomota: An Ode in One Album – A Reflective Essay.p17

The Sankomota sound that Ross heard that day inadvertently fitted the post-punk idiom, making them, possibly, one of the first African bands in the genre. I say inadvertently because a number of their original line-up had left to find work in South Africa, leaving only the stripped down 3-piece combo.

Ross was impressed with their performance and offered to record them. Had he seen them with Tsepo Tshola singing he would have passed them over. Tsepo has a large manly voice with American Gospel overtones – very far from the post-punk new wave music that Shifty was about. Tsepo had taken work with Hugh Masekela in Botswana at his state-of-the-art mobile recording studio there.

An interesting thought regarding singing: Frank Leepa understood how to use a microphone to raise the level of what he was saying. His words were clear and sincere and felt authentic. This was what was appealing about the band. Tsepo’s voice was big and loud and projected well in a large space – church or stadium — and carried acoustically above choirs and suited a very different space to that of a small intimate recording studio.

David Byrne in his book How Music Works (2012) speaks of how microphones changed singing and heralded the era of the crooner –

The microphones that recorded singers changed the way they sang and the way their instruments were played. Singers no longer had to have great lungs to be successful. Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby were pioneers when it came to singing “to the microphone.” They adjusted their vocal dynamics in ways that would have been unheard of earlier. It might not seem that radical now, but crooning was a new kind of singing back then. It wouldn’t have worked without a microphone.

Chet Baker even sang in a whisper, as did João Gilberto, and millions followed.

To a listener, these guys are whispering like a lover, right into your ear, getting completely inside your head. Music had never been experienced that way before. Needless to say, without microphones this intimacy wouldn’t have been heard at all. (Byrne.2012.201)

The Sankomota album didn’t sell well, initially, due to the fact that it was impossible to get radio play. The final work was” …. patently a good album; it’s subsequent track record and critical acclaim confirms that. But no record company was willing to release it.”[3]Lloyd Ross 2010 Ross consequently started his own record company and Sankomota was the first release.

The link between Leepa’s song writing and the wider post-punk/reggae/ culture from which it inadvertently sprang leads me to postulate that Sankomota were not only merging many global musical forces in their sound but were part of an eclectic, post-apartheid afrofuturism[4]Leepa released material under various incarnations of the band spanning two decades and eight albums. that included the band National Wake, Malopoets, Harari and a few others. Kodwo Eshun, in his book More Brilliant then the sun (1995), usually attaches the word diasporic to his concepts of Afrofuturism but I would argue for a Pan African-Afrofuturism i.e. a sense of the African future that the present is now fulfilling. Sankomota were that — a prediction of African salvation existing in a return to the values of the past — even if they were mythical warriors.

Mofokeng talks about the metaphorical House on Fire in the wider South African context. He says:

“the song is about the metaphorical house of South Africa as well, which was literally on fire in the 1970s and 1980s. The white settlers and oppressors of Africans all over the globe can be interpreted as the “witches” in the song and they need to be confronted with thebe le lerumo (shield and spear). This makes House on Fire an important, prophetic song in the liberation efforts as well.”

He feels that Sankomota were not overt about their politicality and couched their message in universality and, what he calls abstractivism:

“Sankomota did not sing with concealment as much as it was with abstraction of sorts. Abstraction that still made sense that is borrowed from the nature of Sesotho as a language. Abstraction is important in Sesotho as a deeply poetic and symbolic language. Sankomota’s first album is an experiment in abstraction and symbolism and I think it is very successful.”

Frank Leepa’s abstractivism possibly has its roots in Thomas Mofolo’s seSotho language novel, Chaka first published in English in 1931. Mofolo retells the story of the rise and fall of the Zulu King, Shaka. The book is an abstracted version of the life of the Zulu King. Using the word “abstract” I mean to underscore the meaning which, according to the Merriam Webster dictionary is “insufficiently factual”. Wamuwi Mbao (2015) says, in the introduction, that much of what has been accepted as fact about Shaka is an artful cobbling from dubious sources. There is precious little that can be verified conclusively.

The book is full of myth, magic and murder and was something of a best seller; translated into French, German, English and Afrikaans.

Going back to Frank’s answer to Kaganof’s question about the origins of the band’s name, there is a link between Chaka and the ambiguity as to whether Sankomota, the warrior, actually existed or was perhaps an echo of some of the noise of Mofolo’s time.

My own abstractivism includes: The Chaka ebook on my hard-drive is in a folder next to the books of Phellelo Mofokeng, Kodwo Eshun, David Coplan and David Byrne. These are all in a folder titled Africa Synthesized containing all of the songs on the Sankomota album and a lot of Lloyd Ross’s photographs taken at the time. Mpo Leepa’s book I have in soft cover on a wooden bookshelf.

A big thank you to Lloyd Ross for his exceptional generosity with all his photos, hard drives and talent.

| 1. | ↑ | 56 Alec ‘Om’ Khaoli, interview, 5 September 2004 (David Copland.2007. In Township Tonight.Ravan/Jacana.) |

| 2. | ↑ | Mofekeng.P.2018. Sankomota: An Ode in One Album – A Reflective Essay.p17 |

| 3. | ↑ | Lloyd Ross 2010 |

| 4. | ↑ | Leepa released material under various incarnations of the band spanning two decades and eight albums. |