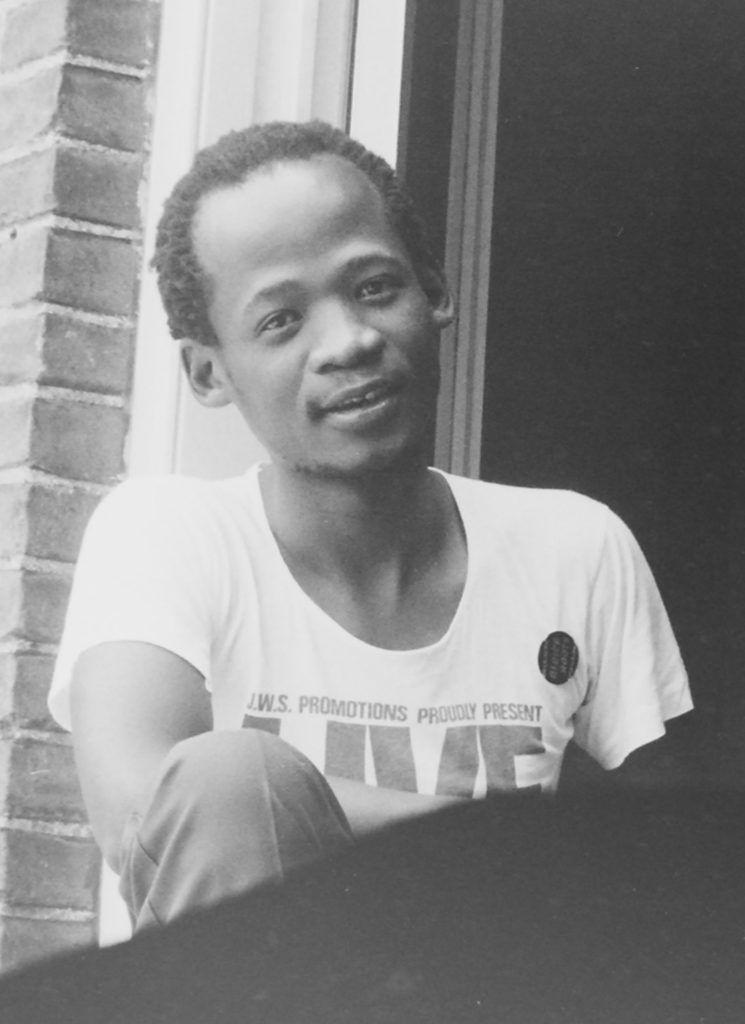

PHEHELLO J. MOFOKENG

Sankomota – An Ode in One Album

Thin light blue plumes of Rothmans smoke curled through the air. The smoke twirled up skywards as if a shaman was summoning a spirit; a muse. The band leader leaned against the outside of the mobile, caravan studio and; with the Rothmans cigarette tightly pressed between his lips, he pulled again. A long and contemplative moment later, he killed the stump on the hard Lesotho ground, a libation of sorts. He surrendered to his muse that he had accordingly summoned.

Frank Mahlomola “Moki” Leepa had the music – all of it – but he needed something to hang it on, to give it character – and Maseru did just that. Maseru – especially at night – was a coveting mistress, a heartthrob for days and an unquenchable partner. This almost-insignificant musical moment for a young band leader would have massive effect on his personal life, his band’s music and history of Lesotho. What seemed to be an insignificant moment, became a spark for musical and political “black swan” effects in the land of Moshoeshoe. Such a tiny musical moment in a nation’s plebeian life, transformed into a “dragon king” that redirected the nation’s fate. And it is fitting that such momentous disruption and glory belongs to Sankomota – a real ‘dragon king’ in the collective musical and political history of the continent.

Perhaps outside of Fela’s Egypt 80, very few music bands have managed to influence their countries in the manner and to the extent that Sankomota did. Their emergence, explosive musical repertoire and longlasting musical effect could neither be predicted nor expected. The effect of their music on the conscience of mortals and politicians alike, can still be felt even today. Maseru was its usual humble self with modest cars driving by and an assortment of shops getting up to their regular busy selves. Many Basotho were preoccupied with the political situation of their fatherland; their bodies wet with sweat of the day’s work and faces gleaming with a kind of resigned happiness that accepted Lesotho for what it was. Basotho – my people – were full of pride, strength and hope; even when their lives fell short and their country was falling apart at the seams, in the tight grip of tyranny.

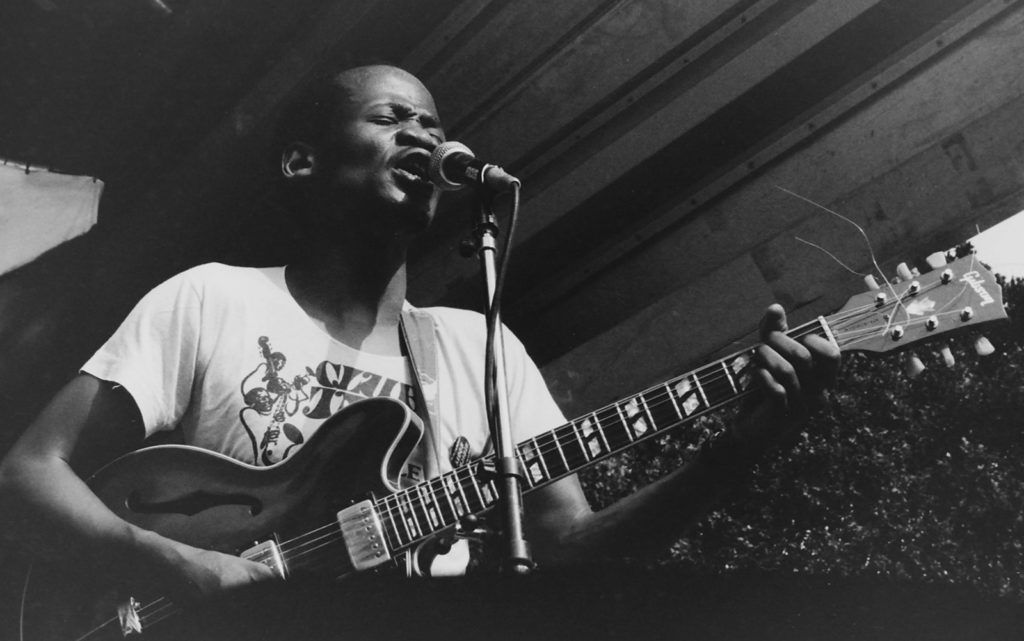

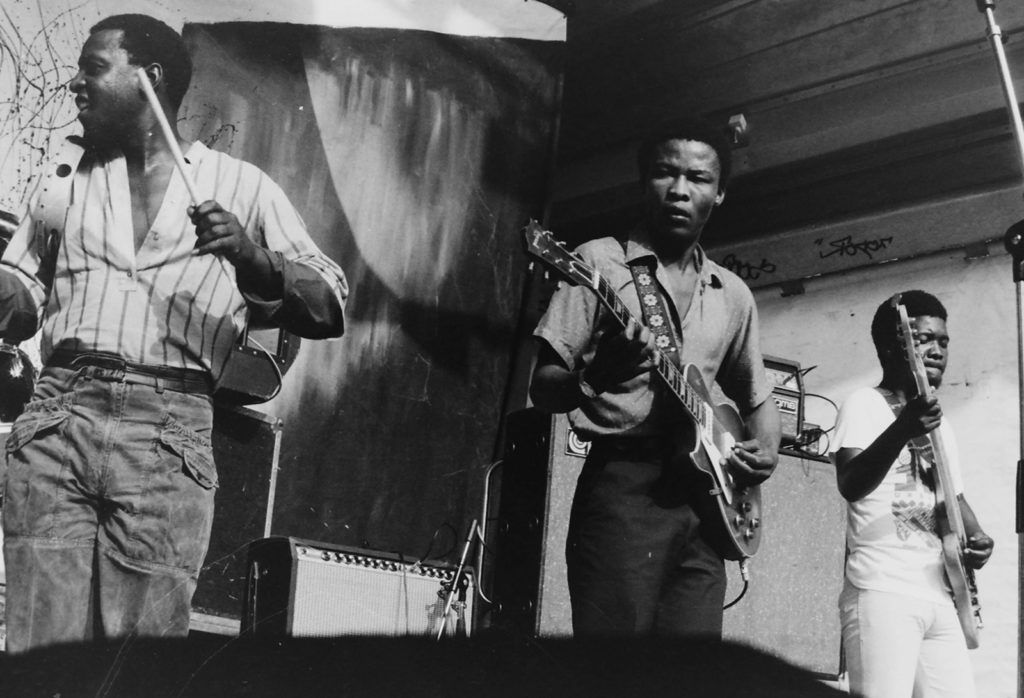

It was a seemingly normal day, towards the end of spring in 1983, when, in this glorious kingdom of Lesotho – a small mobile makeshift studio came to a halt next to the disused Lesotho Radio office. The studio – rather odd-looking in its new home in the land of Moshoeshoe – was the small, independent recording outfit of Lloyd Ross and Warrick Sony; and it was called Shifty Records. In the small mobile studio, was Frank Leepa, Moss Masiu Nkofo and Moruti Selate – and that day they made magic.

They recorded Sankomota’s first album and with this single musical act, history was changed forever. When subjects of Moshoeshoe slumbered that night, they did not know the proportions of history that were made that day. This young band titled the album Sankomota. As they say, the rest is history. Sankomota – with a very powerful album – was let loose with a compact offering of only nine but all potent tracks. The obscure, yet eclectic album was a musical gem, a gentle masterpiece. It was this modest musical nugget that helped the young Basotho band launch a successful career in both Europe and South Africa and throughout the African continent.

Typical with the careers of many bands, many revelers do not know much about Sankomota’s first and self-titled album except for a few songs that can be found in various collections. Sankomota’s Sankomota became an instant hit of an album, a classic and musical yardstick for this band and others. And the band managed to a very large extent, to expand on their first and seminal work, Sankomota in their subsequent albums.

I must hasten to mention that I have been enthralled to the music of Sankomota from the first time I heard Now or Never. Thabang Rampooana was a young legendary disc jockey for Radio Sesotho in the 1980s and 1990s and; one regular summer afternoon, he played Now or Never, one of the most popular songs by Sankomota. I was hooked. Another song that helped break Sankomota into the mainstream was Bakubeletsa, Bakubeletsa is a song that borrowed a lot from the great JP Mohapeloa’s repertoire and genre. It became an instant anthem in our streets. To this day Now or Never and Bakubeletsa remain the most memorable of Sankomota’s songs.

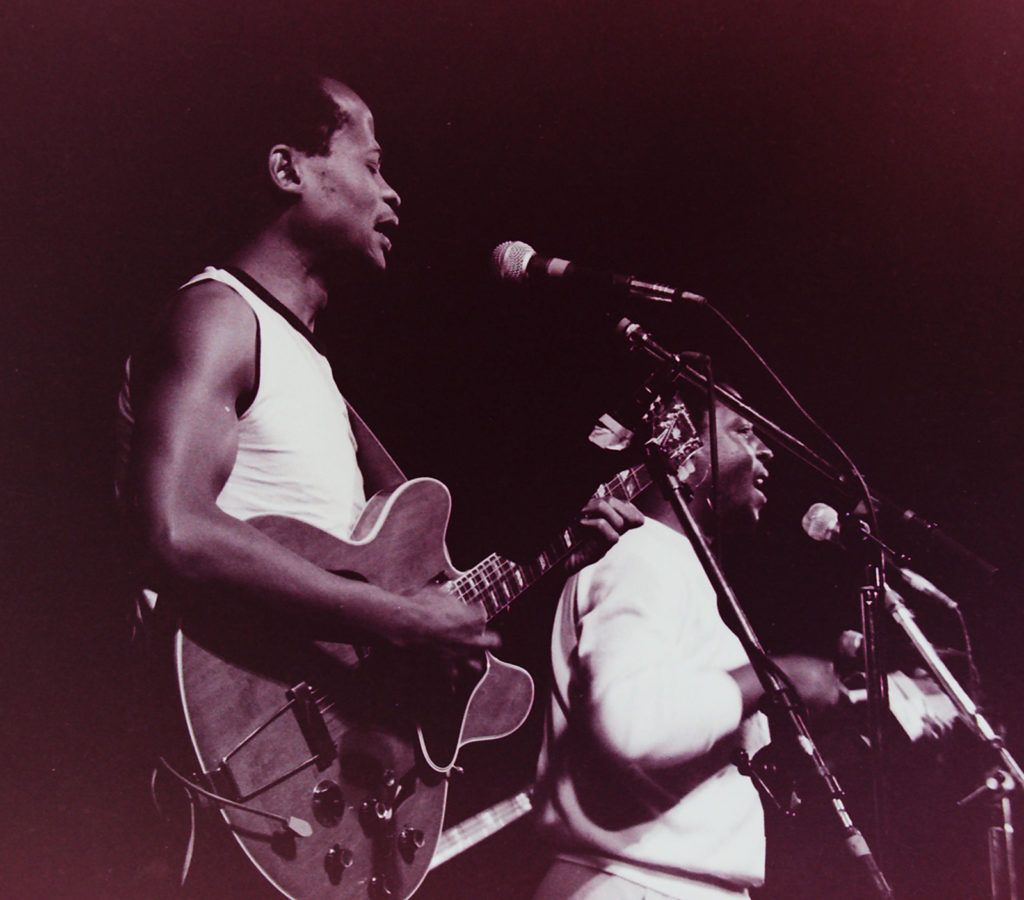

Blondie Makhene mentioned to me that when he heard Now or Never for the first time he was travelling from Johannesburg to Maseru. Blondie Makhene and his brother Papa, are legends of the 1980s disco and struggle songs era. Blondie Makhene’s hit Baby I am Missing You is iconic and memorable. He later popularised banned liberation movements by releasing an album of popular struggle songs. When he heard Now or Never, Makhene says he knew that if that song did not make Sankomota a big and successful band, nothing else was going to. True to word, after Now or Never, Sankomota became synonymous with Sesotho culture and music, black consciousness, anti-apartheid struggle and popular culture.

Sankomota’s musical journey was not just part of the Sesotho music fad of the 1970s and 1980s. Instead it was a musical and cultural totem of immense power and magnificent proportions. The 1980s saw an incredible resurgence of traditional Sesotho language in music, made popular by Mpharanyana, Babsy Mlangeni and Steve Kekana among other musicians. It is my contention that Sankomota rose above this fashionable moment, this “in” thing of that period.

There are two or more reasons for this.

One; disco – mainly sung in English – was coming to an end and many artists were going “back to their roots.”

Two; many artists were gaining political consciousness and care – so they reverted to their languages and directly confronted or ignored the apartheid laws that made it hard for such music to gain airplay. This was fuelled in part, by the rise in popularity of the so-called “traditional” music that was mainly sung in indigenous languages – such as maskandi, mbaqanga and difela tsa ditsamaya-naha.

I suppose the influence of American ballads was also wearing off and artists were getting tired of singing in foreign languages. We can surmise that consciousness was on the rise. Musicians were prepared to throw caution to the wind and risk not being air-played, but at least sing in the comfort of their mother tongues. This artistic freedom was the only one that apartheid could not touch. It was the saving grace of the nation.

Sankomota did not sing in Sesotho (mixed with other languages) just to break away from the monotony of English-language ballads that mimicked America; or the massively popular traditional and modern Zulu music at the time. They sang in Sesotho because it is who they were. The sang in isiZulu and kiSwahili, because this is also who they were. To Sankomota, language was not a barrier or a divisive characteristic of a people – in many instances and in this album in particular – they used all languages at their disposal as a unifying factor or a rallying call for African unity and freedom of Africans.

They embodied the unity that they were to sing about so successfully. They borrowed from isiZulu, Sesotho, English and kiSwahili rampantly – reshaping these languages in their own image, creating new metaphors and genres. I would dare say that Sankomota – outside of the musicians in exile – was one of the leading bands in the anti-apartheid struggle who confronted apartheid directly in and through their indomitable music.

All photos on this page by Aryan Kaganof.

Sankomota: An Ode in One Album by Phehello J Mofokeng is available here. It was published by Geko Publishing in 2018.