At the beginning of his career as a composer, J.P. Mohapeloa wrote words to music that already existed in his head. He explained the process to David Coplan, who interviewed him twice in the late 1970s and who generously shared his field notes from these interviews with me:[1]Coplan’s notes are written on field cards, and are full of abbreviations. More information on the translation process is given in the ‘General Introduction’, liv-lv.

Mohapeloa finds it easiest to write music, with a theme or subject in mind, then it becomes easier to fit words to it. Idea to melody to words. (Coplan 1978a)

Mohapeloa finds the words a handicap if they are there first. Once the music is there the words just come. The tune suggests the words. Like in his first song … the music suggests a folktale about a rabbit & so the words just came. The words then necessitate changes in the melody, to avoid semantic distortion. So the words can damage the melody. To get a word that just fits the tune is a struggle & may have to be an ‘expensive’ one. This difficulty actually helps to improve the quality of the lyrics – the words tend to be commonplace if they come too easily.

The words of Mohapeloa’s songs are almost without exception his own, and describe everything under the sun in Lesotho and in the experience of Basotho. He uses language poetically and exploits the way Sesotho is rich in metaphorical allusions and embedded cultural knowledge. This richness often made finding the right words in modern English difficult. I was very lucky to have Dr Mantoa Motinyane, a linguist in the Department of Southern African Languages at the University of Cape Town, translating the texts for me, and we worked together for several years. I extracted the text of each song from Mohapeloa’s original songbooks – mostly, the words are not written separately – and sent these ‘poems’ to her in batches to translate.

In copying the words, I frequently made mistakes because of my limited knowledge of Sesotho, but it was easier for Mantoa if I did it this way, because for her to pull words out of a small-format, densely written tonic sol fa score where the music is text as well, was even more difficult. (And such a close study of the texts, which I later had to add to the scores I was typesetting, was invaluable.) I asked Mantoa to translate each word or part of a word literally, placing the literal English translation exactly below each phoneme in the Sesotho, line by line. In Sesotho, each syllable is extremely important because it often indicates voice, tense, singular-plural, and so on. Mohapeloa wrote in an older Sesotho that younger people do not generally speak nowadays, and some words have fallen out of use altogether.

After making the literal translation under the Sesotho, Mantoa wrote a rather literal poetic translation, and then a more nuanced poetic version, line by line. Eventually this became a two-column rendering of the text: the Sesotho with literal phoneme-by-phoneme translation below each syllable or word in the left-hand column, and a flowing English translation on the right, matching line for line. What I wanted was to place this two-column text of the song below my ‘Historical Introduction’ on the inside front cover (p.2), so that the music began on page 3, following the norm in many music scores. Sometimes it was difficult to squash the words into the available space and I often used 8 or 5-point type. I was still thinking, in this first edition, of print format and a conventional vocal score rather than online format, where space is not an issue.

In 2014, when I was approaching completion of the first edition, I obtained additional translation services from Mpho Ndebele, on the recommendation of Dr David Ambrose, a Lesotho expert who had known Mpho and her husband (Professor Njabulo Ndebele) at University in Lesotho. David suggested that the translations occasionally needed tweaking by someone steeped in an older Sesotho culture. Mpho’s changes were often based on her memory of singing the songs at school, and the way she remembered them as ‘sung texts’ brought a new perspective that Mantoa was very happy with. In turn, Mpho acknowledged Mantoa’s role, noting that she ‘had already done a lot of literal translations and my assignment tended to be more on the column of the poetic side, which I enjoy more, I think, with my broad experience in literature, history and the region, I can tell you, that it is easier than the literal translation, which I think requires a linguist’ (Ndebele 2017).

As a result of many discussions about the way Mohapeloa molded language to music, Mantoa and I gave a joint paper on this topic at the South African Folklore Society conference at the University of Cape Town (Motinyane and Lucia 2013). In 2016, after I had worked with Mpho on Mohapeloa, we began developing a translation policy for a new project on Michael Moerane, during the course of which we were struck by something Daniel Kunene says in the ‘Preface’ to his translation of Thomas Mofolo’s Sesotho novel, Pitseng:

I’m fascinated by the challenges of translation and its end-goal, namely sharing a work of culture with those otherwise barred from it by language … As a translator, I try and take the reader to a culture where they have never been, to tempt them to take leave of where they are in time, caught up in how the world works here and now. They should feel that they are traveling physically from wherever they are, to Lesotho … I have sometimes taken the liberty of a ‘translator’s licence’ or maybe I should say the translator’s poetic licence, and done some minor editing [in order] to enhance the understanding and comprehension of the story. (Kunene 2013, v-vi)

It was not too difficult to apply the idea of taking the audience to the original writer’s culture, because Mohapeloa’s texts are full of descriptive, often vividly realistic detail. Our main difficulty, perhaps, lay in knowing how far to extend ‘poetic licence’. Mohapeloa uses metaphors deeply rooted in traditional Sesotho culture. The song ‘Mabeoana’ (Vol. I, 199) sounds quite obscure in our English translation and it is not easy to explain every line because there may be more than one interpretation of what words or phrases amount to, what they are referring to historically, what is implied just below the surface. We did not dig these things out, because there was no time and also because even if we had done, not all Basotho would necessarily agree with our interpretation, and the critical edition was not about interpreting Mohapeloa, nor was it the place to enter into cultural debates about Basotho history. When in doubt, nevertheless, we added footnotes to ‘enhance understanding and comprehension’, as Kunene puts it.

We live in a time of many ‘Englishes’. What we did not address in any depth was who our target was, really. Indeed, it had to be a very broad target: anyone in the world who wanted to sing these songs, since they were to be available for sale online. That raises another interesting issue, namely the way Mohapeloa himself translated those few songs for which we have his translations, because they were made for a very specific person: Yvonne Huskisson at the SABC (Mohapeloa and Huskisson, n.d.). Mohapeloa knew that she might use his translations, which are sometimes rather free and more ‘explanation’ than ‘translation’, when compiling programmes for Radio Bantu.

His translation of ‘Tlholohelo’ (Vol. I, 210) for Huskisson is a case in point. He translates the song title as ‘loneliness’, but a stronger meaning is ‘longing’. Similarly, the ambiguous words in the first line, ‘tšepe’ and ‘noto’, are translated as ‘springbok’ and ‘notes’.[2]Depending on the tone, ‘tšepe’ may mean ‘iron’ or with an ‘h’ (‘tšephe’) a springbok or gazelle. ‘Noto’ can mean ‘hammer’ or (musical) ‘note’. Thus, Mohapeloa writes, ‘With notes running like a Springbok’, rather than ‘Strike the iron with a hammer’, perhaps to soften the message of the song. He left out some details, too, softening the rawness of the message.[3]The text is written from the point of view of a Mosotho migrant working in brutal conditions on the mines of Gauteng, who longs for home. In the critical edition, we offer an alternative translation of the whole text, which makes it clearer that the place being described is Gauteng, centre of the mining industry. The two translations juxtaposed, Mohapeloa’s in the middle column, Mantoa-Mpho’s in the right-hand column, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 ‘Tlholohelo’ (Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa Critical Edition 2016, Vol I no. 21)

An interesting feature of the translations that Mohapeloa made for Yvonne Huskisson in 1965 is that he used South African Sesotho orthography rather than Lesotho Sesotho orthography, presumably because he knew that this was the ‘official’ Sesotho of the SABC. It was a pragmatic choice, made in order to have his work disseminated more widely on radio, perhaps. Mohapeloa was well aware of the issues around orthography. He is one of the people thanked as a proof-reader by R.A. Paroz in his new edition of Mabille and Dieterlen’s Southern Sotho-English Dictionary (Mabille and Dieterlen 1950), which uses Lesotho Sesotho orthography; but his name does not appear in the preface to the next edition, where Paroz controversially introduced the new South African orthography. This could mean that Mohapeloa did not wish to be associated with it. He lived in Lesotho for most of his life. With time he became an institution and produced songs for the most important national occasions. Yet when he encountered South African officialdom, either in the form of the SABC or – in another instance – in the form of the African mission of Die Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church) in South Africa in Potchefstroom, a body which commissioned his late 1970s settings of Psalms (see Vol. V, 1291-3), he used the South African Sesotho orthography.

Lesotho still uses the original Sesotho (sometimes called ‘Southern Sotho’) orthography, developed early in the 19th century by Swiss-French missionaries. The new South African orthography was introduced in 1959 by the South African government through their Bantu Education Department. When Sesotho was originally codified by French-speaking people, the ‘w’ and ‘y’ sounds were written ‘o’ and ‘e’, more familiar sounds in French, where ‘w’ or ‘y’ are hardly used. Thus the sound ‘wa’ (in the new orthography) was written ‘oa’, and ‘ya’ was written ‘ea’. Other new spellings in the South African orthography are ‘di’ (‘li’) and ‘du’ (‘lu’).

Rather than tread further on the minefield of orthography, I leave it to my translators, who discuss it further below.[4]The Wikipedia entry on Sesotho is very informative. See, accessed 12 December 2017. For this introduction, I asked Mantoa and Mpho to answer some specific questions about the process of translation.

Is it obvious from reading the texts that he had music in mind when he was writing the Sesotho lines?

Mpho: Because I’m not a musician, it is hard for me to tell how music text is developed. But the repetitions and the exclamations, including the poetic nature of his writing seems to imply that he had music in mind.

The song ‘Hook Haneeu!’ (‘Stop, Stop!’), one of my all-time Mohapeloa favourites, was clearly written for music; so, too, ‘Leeba’ (‘The Dove’) and ‘Qeu! Qeu! Majoana’ (‘“Knock, Knock” Go the Pebbles’). In some cases, Mohapeloa takes Sesotho rhymes, folk tales and hymns and turns them into beautiful music e.g. ‘Sika la Tholo, Khaoha’ (‘Genealogy of Tholo, Break’) or ‘Obe’ (Obe is a mythical one-eyed being).

Mantoa: In Sesotho, music, oral literature (folk stories) and praise poetry take more or less the same structure. One of the obvious characteristics is repetition. This is often either at the beginning or the end of lines. In the song, ‘Mo-Afrika, Tsoha’ (‘African, Arise!’), this is evident where we find the following alternations: ‘borokong’ (from sleep) in line 1 and ‘boroko’ (with sleep) in line 5; ‘mosebetsi’ (work) in lines 2 and 6; ‘hohle’ and ‘tsohle’ (all) in lines 3 and 4. This is an indication that Mohapeloa wanted the rhythm associated with both music and poetry in Sesotho. Since folk tales often employ music, it makes sense that he decided to weave these together into folktales/poetry/music.

How did Mohapeloa adapt or develop the Sesotho language as he went along? (The first songs are from the early 1930s, the last include some writing in the 1970s.)

Mantoa: The changes over the years are more concerned with the topics rather than the orthography. There is some reduction over the years of contracted forms of words. Perhaps this is a reflection of a change from where the notation was not dictating the word structure. Putting this in other words, Mohapeloa allowed Sesotho to be expressed in ways that are familiar to the ear, rather than forcing Sesotho to fit in with his music notation.

Mpho: Through the poetry in his songs, Mohapeloa exposes Sesotho speakers to the complexities of life and at the same time, to the beauty of the language. Take ‘Hook Haneeu!’, with the ‘furious’ horses pulling their cart and cantering, the horse riders struggling with the reins, the sound of the hooves hitting the cobblestones in a rhythm. The horse riders in this case are said to be novices that are being asked to step aside to allow the experts to take the reins and demonstrate how to handle such a magnificent performance. In the past, most Basotho men were expert horse riders. Here Mohapeloa demonstrates a complex relationship between horse and man, yet uses the most beautiful words and music.

What are the main difficulties encountered in translating from Sesotho to English? Is it more the syntax or more finding equivalent vocabulary?

Mantoa: As with any translation, there are always challenges. As Gill Paul, the editor of a symposium on Translation in Practice (Paul 2009, 41) points out, ‘every book is different and presents its own problems’. In the instance of Mohapeloa’s songbooks, we worked with a series of books and individual songs spanning a number of decades, representing a number of changes in terms of orthographic conventions. Secondly, the music was presented following poetic conventions and structures associated with folklore. Additionally, translating Sesotho, a South Eastern Bantu Language, to English, an Indo-European language, presented challenges at a number of levels. These are discussed individually in the next four paragraphs.

Sounds

First of all, Sesotho music, or rather text, relies heavily on onomatopoeia. Onomatopoeia is the formation of a word by imitating a sound associated with the referent.

In the song ‘Qeu! Qeu! Majoana’ the words, ‘qeu que’ are associated with the sound made by small rocks or pebbles, or the sound when they hit another item, in many instances a hard object. The translation, ‘knock, knock’, does not even begin to do justice to the meaning associated with the word in the source text. It was therefore very challenging translating imitations of sounds. However, during the discussion with Professor Lucia, we agreed that we would provide three levels of translation, the morpheme-by-morpheme, the literal, followed by a more poetic form. It was indeed difficult imagining the same objects making different sounds in different languages. This highlighted the deeper connection between perception and language and perhaps culture and language. We find similar challenges spread across a number of songs. ‘Sealolo sa Baroa’ (‘Dance of the San People’) provides a nice example of how difficult translating can be when the sound systems of the source and target language do not overlap. Clicks can only be translated as clicks as these do not exist in English. Another song that presented a similar challenge is ‘Pina ya Batšosi’ (‘Song of the Scarecrows’) where different sounds are used for chasing away different types of birds.

Terminology associated with specific events

Perhaps this was the most difficult part of the translation process. Firstly, it required a thorough knowledge of the history of Lesotho as well as the names of the events in order to find relevant information that was useful in providing background for the translations. Secondly, because of the differences in orthography, it was rather difficult finding terminology in South African Sesotho orthography. This indeed complicated searching for relevant information. Thirdly, the issue of age differences (between the translator and the author) made it very difficult to understand the context. This is where the poetic translation became relevant.

Praise names or clan names

Language and culture go hand-in-hand. This was the case with praise names as well as genealogies. In this instance, where one’s name/clan name was praised, the ‘beauty’ associated with the source is lost in translation. For example, ‘Shoeshoe tsa Moshoeshoe’ (Vol. 6, 1592) is an instance where a sound of the name is repeated for poetic effect. The translation of the title as ‘Moshoeshoe’s Marigolds’ loses the original appeal.[5]The word ‘marigold’ is important in the song, since marigolds decorate the land but are also a sign of life to come. Children should be treated like flowers, the song suggests, because they serve a similar purpose. We therefore decided to provide the literal meanings but at the same time tried to retain clan names in an effort to conserve the melody of the source text.

Sentence structure

This was a challenge at a slightly different level. Sesotho has a very elaborate verbal inflection system. The various agreement markers on the verb/predicate make it easy to move the verb’s complements to different positions in a sentence depending on the effect that the author wishes to achieve. Since English is a less inflected language, some sentences become very awkward if the word order of the source is retained. The agreement markers also meant that in some instances the subject/object had to be omitted. This would be ungrammatical in English. It was therefore necessary to provide additional information to make it easier for the reader of the translated text to follow the song/story. Examples include the omission of plural form which can only be interpreted based on the agreement, for example nonyana = bird or birds, khomo = cow or cows. Here is another example, from the song ‘Mafeteng’ (Vol. II, 575):

Taba tsa teng ke makatikati;

The news from there is confusing;

[News of there is confusion]

Li ka nka bosiu; le letsatsi.

It can take all night and day [to tell].

[They can take night and day]

In the example above, we can see how the subject, ‘[li]taba’ (news) is omitted in the second line, which requires an adjustment to the translation to satisfy the requirement that the English sentence must have a subject.

Mpho: The main difficulty was syntax, because Sesotho sentences are structured very differently from English sentences; and finding the right vocabulary too, was not easy. Regarding sentence structure: here are some phrases from the phoneme-by-phoneme literal translations where English follows Sesotho word order exactly, which bring out some of the differences between the languages:

u ea kae? (Vol. I, 4)

you go where?

ha kea u bona (Vol. I, 37)

not I you see

khutsa, meokho u e hlakole (Vol. I, 65)

be quiet, tears you them dry

le karohano ena ea kajeno (Vol. I, 75)

and separation this of today

fatše la heso (Vol. I, 95)

country of our

To add to this: I think Sesotho is a language more steeped in its culture and values than English is. For example, family relationships are not simply ‘mother, father, brother, sister’ etc.

There are many different words for family members in Sesotho. Is it the age of the person being addressed that determines what word is used or is it the person addressing that changes things? Could you just clarify?

Mpho: There are different words for ‘sibling’: for example ‘khaitseli’ means either ‘my sister’ when said by a brother or ‘my brother’ when said by a sister, so it is cross gender. Brother addressing brother would be ‘moreso’ or ‘moena’, depending on age. ‘Moena’ would be younger than the addressor. Sister to sister would be ‘moholoane’ or ‘’nake’ depending on age. ‘’Nake’ is the younger one being addressed by either sister or brother. This explains why ‘ngoana ‘me’ ’ – ‘child of mother’, which implies ‘sibling’ without being too specific – is easier to use.

The second (maybe actually the first) reason for using ‘ngoana ‘me’’ is that in Sesotho, when people indicate that they share a mother it expresses how close and intimate they are, which is why it is common in the Sesotho language to talk of siblings having shared ‘letsoele’, the breast. In music, I think first and foremost composers wish to express the intimacy of the siblings; the rest (sadness, disappointment, excitement) follows once you understand this close bond of sharing the breast.

To say ‘my child’ one has to say ‘ngoan’a ke’ which literally means ‘child of my’. Another example is the way people are identified by their clan such as Bataung, Bakoena, Bafokeng, Basia, etc.

A more complicated example is the way Sesotho interprets the words brought to them by the missionaries for ‘God’, ‘Lord’ (Jesus), ‘Holy Ghost’. The word ‘morena’, for example, which comes from the indigenous root word ‘rèna’, meaning ‘to be rich’ or ‘not to work’, can mean ‘God’ in some contexts or ‘Lord’ in others.I found the meaning in Paroz’s dictionary (Mabille and Dieterlen 1950). I see from the big file with all our translations that we’ve used ‘God’, ‘Lord’, ‘chief’, and ‘king’, depending on the context. In yet other contexts, ‘God’ is ‘Molimo’ which means ‘of above/of up high’. The word ‘moea’ means ‘wind’ ‘breath’ or ‘spirit’ but came to be used for ‘Holy Ghost’.

Mpho: This is an interesting meaning of ‘réna’ that I have never heard of. As far as I know ‘ho rena’ means to reign/to rule, butI have checked Paroz and found the ‘réna’ meanings you bring up. I asked two Basotho about this and both (like me) did not know this meaning. Anyway, it is what it is. Holy Ghost is ‘Moea O Halalelang’: ‘ho halalela’ means ‘to be holy’.

Moshoeshoe, Tsoha – (Come Back, Moshoeshoe) – Sung by Itlotliseng Secondary Choir, Witzieshoek, under leadership of L. Ramathe at the Independence Day Celebrations in October 1966

Something else: what exactly does the ’ before the first m in the syllable ‘’m’ do? Is it an actual sound, or does it indicate a way of closing the lips to pronounce the ‘m’? I’m trying to understand why Lesotho Sesotho orthography has ‘’me’ and South African Sesotho ‘’mme’, and relate this to the way Mohapeloa sometimes writes two notes for this word, implying ‘m-mé’.

Mpho: Please note: ‘’me’ is not the same as ‘’me’’. The first ‘’me’ means ‘and, however, yet’ – it has many meanings. ‘’Me’’ means mother. Don’t forget that Sesotho writing by the missionaries was influenced by French and Arabic. So those apostrophes would change the sound of the word. Sesotho does however change the spelling when the sound of stressing the ‘m’ is in the middle of the word, eg. hammoho, meaning ‘together’; while ‘we are together’ would be: ‘re ’moho’.

Why did Mohapeloa keep mainly to Lesotho Sesotho orthography?

Mantoa: The choice of the orthography, whether in South Africa or Lesotho was determined by the publishing houses as well as socio-political motivations. In the case of South Africa, the revisions of orthography, as much as they were geared towards the standardisation as well as the harmonisation of orthographies, were also used as some means of monopolisation by the publishing houses. Since the changes were very different from the earlier versions, this discouraged earlier established writers from submitting their manuscripts. (See Pieres (1980) for an account of orthographic challenges at Lovedale Press.) It would therefore make sense for Morija Press to resist such changes, as it would mean that it would have to rely on South Africa, thus allowing the country with minority speakers to take control of the language. In her workshop paper on unifying orthographies, Demuth (1989) points out that in the early 1900s it was not yet possible to unify orthographies of the Sotho languages. In the late 1940s however, when Bantu Education was introduced in South Africa, there was a renewed call for the unification and revision of the Sotho orthographies. This was only partly achieved because the experts in Lesotho were not receptive and instead continued with the ‘old’ orthography. It would make sense therefore for Mohapeloa, despite having worked and lived in South Africa, to continue using the old orthography now known as the Lesotho orthography.

Mpho: Why not? I’m not sure why the question is being asked. I think Mohapeloa was writing in Sesotho for Basotho of Lesotho, first and foremost. Besides, when he first wrote music there was only one orthography of Sesotho in the whole sub-Saharan region and that orthography was what is now called Sesotho of Lesotho.

Mohapeloa was a very patriotic man; he loved Lesotho with all his heart and it comes out in the majority of his texts. For example, several songs in Meluluetsa ea Ntsetso-pele le Bosechaba Lesotho (Anthems for the Development of the Nation of Lesotho) have highly patriotic lyrics, for example: ‘Lesotho ‘ma’ Basotho’ (‘Lesotho, Mother of Basotho’), ‘Likano tsa Bacha’ (‘The Youths’ Oaths’), ‘Terompeta ea Rona’ (‘Our Trumpet’ – which is about the language Sesotho), ‘Naha ea Linatla’ (‘Land of Warriors’), ‘Moshoeshoe, Tsoha’ (‘Moshoeshoe, Arise’). Then take the songs when he laments times when a Mosotho is away from home: ‘Molako-lako’ (‘The Wanderer’) and ‘Mohahlauli’ (‘The Traveller’). For both songs, the travel is just across the border to South Africa (Johannesburg), but it comes across as wandering far away, to a place where one is not too well received. Whenever Mohapeloa wrote about Lesotho he expressed pride to be born in Lesotho – the land of beauty, mountains, rivers, cliffs, ridges, land of warriors. The examples are endless.

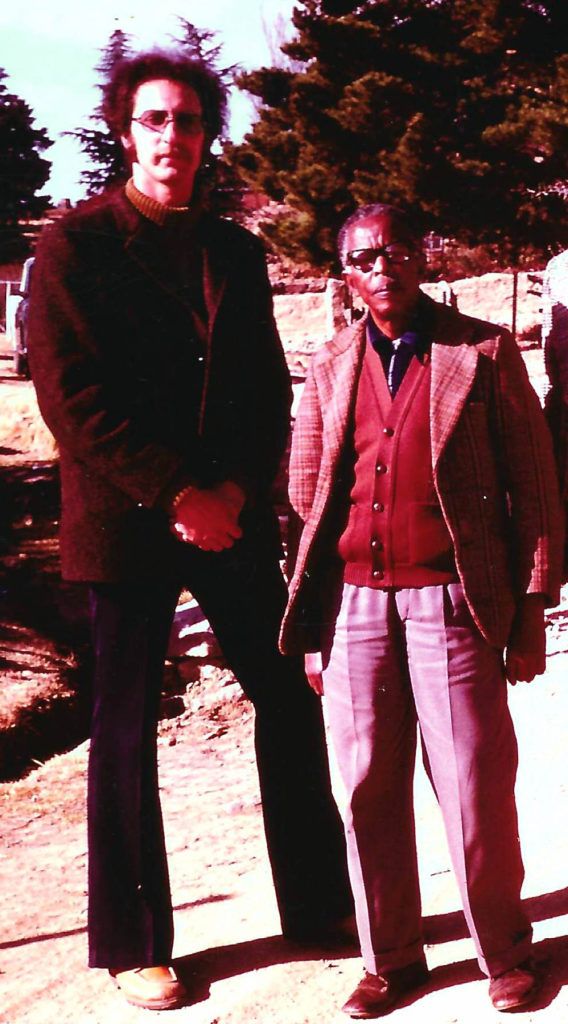

U Ea Kae? – Where are you off to? – Ionian Male Voice Choir conducted by Khabi Mngoma (father of Sibongile Khumalo)

What contribution do his poems make to Sesotho literature?

Mantoa: Mohapeloa has made tremendous contributions to Sesotho literature. As indicated above, his work is not only seen as music collections. The writings and themes reflect Mohapeloa’s growth as a writer and composer, they reflect the influence of the environment, they reflect the events both in his family and surroundings, they reflect his upbringing and the impact of religion, they reflect political struggles and many more. In terms of appealing to literary theorists, it can be said that his work demonstrates different challenges that writers are grappling with today: the issue of transitioning from oral to written literature, and the issues of copyright and communal intellectual property. The work transcends issues of intertextuality on a number of levels.

Mpho: J.P. Mohapeloa is the most famous Mosotho composer not just in Lesotho but everywhere where his compositions are known and used. He was a prolific writer and the imageries expressed in his lyrics make for very good poetry. His compositions have exposed musicians to the history of Lesotho, the topography and geography of the country, to the need to care for nature and the environment, and to the human relationships, beliefs, culture and values of Basotho.

Coplan, David B. 1978a. Unpublished field card no. 6 In778/2 ‘Composition & Composers’.

Coplan, David B. 1978b. Unpublished field card no. 7 In778/2 ‘Composition’.

Demuth, K. 1989. ‘Unifying Organizational Principles in the Development of Orthographic Conventions’. Paper presented at the Workshop on Orthography, Maputo, Mozambique, 1988. Accessed 10 December 2017.

Kunene, Daniel. 2013. ‘Preface’. In Thomas Mofolo, Pitseng: The Search for True Love, tr. Daniel Kunene. Morija, Lesotho: Morija Museum and Archives, v-vi.

Mabille, A. and H. Dieterlen. 1950. Southern Sotho-English Dictionary, reclassified, revised and enlarged by R.A. Paroz. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot.

Mohapeloa, Joshua Pulumo and Yvonne Huskisson. n.d. ‘Korrespondensie’ [Correspondence]. Huskisson Collection, Southern African Music Rights Organisation Archive, Johannesburg.

Motinyane, Mantoa and Christine Lucia. 2013. ‘J.P. Mohapeloa in Poem and Song: A Critical Analysis of the Linguistic and Poetic Influence of Mohapeloa’s Notation’. Paper presented at the 13th Regional Conference of the South African Folklore Society, Cape Town, 4-6 September.

Ndebele, Mpho. 2017. ‘On Translating Moerane’s Song Texts’. Presentation given at the Andrew Mellon Moerane Critical Edition Research Workshop, Stellenbosch, 30 September.

Peires, Jeffrey. 1980. ‘The Lovedale Press: Literature for the Bantu Revisited’. English in Africa 7(1), 71-85.

| 1. | ↑ | Coplan’s notes are written on field cards, and are full of abbreviations. More information on the translation process is given in the ‘General Introduction’, liv-lv. |

| 2. | ↑ | Depending on the tone, ‘tšepe’ may mean ‘iron’ or with an ‘h’ (‘tšephe’) a springbok or gazelle. ‘Noto’ can mean ‘hammer’ or (musical) ‘note’. |

| 3. | ↑ | The text is written from the point of view of a Mosotho migrant working in brutal conditions on the mines of Gauteng, who longs for home. |

| 4. | ↑ | The Wikipedia entry on Sesotho is very informative. See, accessed 12 December 2017. |

| 5. | ↑ | The word ‘marigold’ is important in the song, since marigolds decorate the land but are also a sign of life to come. Children should be treated like flowers, the song suggests, because they serve a similar purpose. |