LEONHARD PRAEG

Night Music 5: A Melancholy Anatomy

Notes on Arnold van Wyk’s Nagmusiek[1]The opening paragraph should make it clear that that this is in no sense a review of this new release but at best a little programme note of sorts.

I

Molto lento

“The Demon is not the Other, the opposite pole of God, the Antithesis … but rather something strange and unsettling that leaves one baffled and motionless: the Same, the perfect Likeness.“[2]Michel Foucault, ‘The Prose of Actaeon’, in Pierre Klossowski, The Baphomet, Eridanos Press, Hygiene, Colorado, 1988, ppxxi-xxxviii.

The invitation came out of the blue:

“Dear Leonhard, I hope this mail finds you well. I also hope that you will be interested in the following invitation to write. The Africa Open Institute is publishing an online cultural journal called herri of which I am curator. You are the only person I know of in South Africa who is both a philosopher and a composer and a novelist. For this reason I would like to invite you to respond to Daniel-Ben Pienaar’s recording of Arnold Van Wyk’s Nagmusiek which will be released as a CD in 2020. I propose to send you the recording as a .wav file as well as Stephanus Muller’s large book on the subject (itself titled Nagmusiek) by way of background reading. The invitation is entirely open – in the sense that I encourage you to write creatively about the music in any way that you are moved to. It could be literally whatever you want it to be – fiction, philosophy, musicology, a mixture of all of these, a mixture of none of these. A really open invitation”.

It was almost as if, compelled by the logic of friendship, I felt obliged to accept the invitation without thinking about it too much – “isn’t that what friends are for?” I wasn’t too concerned about the fact that I had never heard of Arnold van Wyk (my history of music runs from J.S Bach through Miles Davis and Fela Kuti to Arvo Pärt); nor did it bother me that I had no idea who Stephanus Muller is or that I was unaware that said Stephanus had written a “large book” on, and in, a subject I didn’t know anything about – a book which turned out to be a moving exercise in Daemonology; a “large book” that collapses the modernist distinction – assumed necessary for any biography – between the subject being written about and the subject who is doing the writing; a meditation, titled Nagmusiek, on the life of the individual who composed Nagmusiek: a doubling over, then; an (auto)biography about another subject; an “exorcise” in Daemonology, on how to become oneself by becoming another, the result of which is something strange and unsettling that leaves one baffled and motionless: the Same, the perfect Likeness.

But I am going too fast. I need to slow down because that is the required tempo for this particular opening: molto lento/very slowly.

What is the meaning of the composition Nagmusiek? Is that even a real question? After all, if Van Wyk could have answered that question he would not have needed to compose the piece. The meaning of a musical composition is always radically irreducible to the meanings language can ascribe to it. We can circle Nagmusiek like a pack of hyenas, but we can’t tear at its flesh.

Usually one would have two choices: on the one hand, to speak about Nagmusiek’s residual meaning as if about ourselves (does Nagmusiek still speak to our contemporary longing for love, sleep and death?); on the other hand, to trace the meanings that accumulated throughout Van Wyk’s life and which made the piece possible; not what it means, but what meanings made it possible. But neither of these options are open to me because I listened to Nagmusiek while reading Nagmusiek, and then re-read the text having listened to Nagmusiek. By the time I started writing I knew that my reflection would slip between the residual and the cumulative, between one Nagmusiek and another.

Placing the release of this new recording of Nagmusiek in the context of the herri project compels me to begin by going to the heart of a central contestation: Van Wyk as nationalist composer who, admittedly in his youth, thought of himself as doing “it” for his people and who, in return for that willingness, benefitted significantly from opportunities made possible by the state apparatus under control of the Afrikaner Nationalists. While it cannot be denied that there was indeed a symbiotic relationship between the rise of Afrikaner Nationalism (more specifically the creation of the legitimating myth that Afrikaner artists were capable of producing “high art” on par with what European artists at the time were offering), the challenge is to understand the nature of that symbiotic relationship. How should we interpret and understand it? For Strauss[3]Suzanne Strauss, “ ‘Ek kan eintlik net hartseer musiek skryf …’. Die selektiewe kanonisering van Arnold van Wyk (1916-1983) se werke’ in LitNet Akademies, Jaargang 10, Nommer 2, Augustus 2013. the symbiosis consists in the way the myth of Van Wyk as lone, melancholy artist obsessed with love, passion and death was cultivated and canonised in order to establish, what I would suggest to be, a second order symbiotic relationship between Afrikaner and Western art(ists): “The Romantic artist myth supports Afrikaner nationalist agendas, and Afrikaner nationalist agendas encourage the characterisation of Van Wyk according to the Romantic artist myth.” We also have a Chopin.

Other descriptions of the nature of this symbiosis are less interesting, in part, because Van Wyk’s complex relationship with/to his Volk simply becomes grist to the mill of lazy efforts at “decoloniality” – lazy because the reduction comes with pre-packaged interpretations and understandings of which the sole advantage seems to be that they don’t require any real thinking. And so we find Van Wyk’s intrepid (auto)biographer recounting an experience of attending a conference at Rhodes University convened in order to “reflect on compositions in the years of apartheid when white composers – the current whingers! – were having a pretty good time, thanks to their great patrons, the old National Party … Never before (or since) had so much mediocrity reached such heights” (III 379).[4]Stephanus Muller’s Nagmusiek consist of three volumes. In all cases I simply refer to the volume and page number. The laziness of thinking here consists in the uncritical and unreflective replacement (or rather displacement) of one symbiosis with another: Van Wyk’s assumed uncritical and therefore cosy relationship with the Nationalists is criticised (not critiqued) from the vantage point of an uncritical and cosy relationship between the conference organiser and a discourse on decoloniality. The author of the conference blurb is not interested in interpreting and understanding any fissures that may have existed between Van Wyk and the Volk and so remains incapable of interpreting and understanding the fissures that should (one would hope) also exist between himself and the easy-going demands of the rising new nationalism implicit in “decoloniality”. And so, the alleged mediocrity of composition is displaced by the mediocrity of thinking.

The lazy narrative of complicity and decoloniality generates residual meanings, a number of excesses, which cannot but remain unaccounted for. To highlight some of these let us distinguish between the individual subject Van Wyk and the collective Subject “the Afrikaner” or Volk. On the frayed margins of the simplistic narrative of complicity and collusion (which collapses into Sameness the desires of the collective Subject and individual subject), we find Van Wyk’s well documented disdain for the politics of his day: “I’m working now with earplugs and SOUL PLUGS, too, so that I’ll forget … the formation of the NATIONAL Arts Council (that’s the way it started in Germany – soon they’ll be burning the books)” (III 184). But that is the easy one. More irritating about the complicity narrative is its own failure to capitalise on what it would mean to posit a collective (hetero-normative, patriarchal) Subject who purportedly expressed itself metonymically through/as an individual subject and vice versa; a narrative about a “cosy relationship” in which the subject becomes synecdoche of the Subject. The complicity narrative fails to capitalise on what is most interesting about this reduction, namely the fact that the individual subject’s homosexual longing for sameness was neither condoned nor condemned by the Subject. Instead, it was displaced, deferred and exorcised from the Subject’s own desire for the Same and perfect Likeness which assumed the form of a policy called Apartheid. (Of course, had the subject’s desire for sameness ever become a bone of contention – which it never did – we can fully expect that only its desire for the Same would have been marked and condemned as representative of the Antichrist).

Still too fast. I managed to start with a such a nice, sombre Nocturne about friendship and now already find myself mid-Scherzo. I need to go back yet again: molto lento.

Let me start with another suggestion; one that will structure the symbiotic relationship between Van Wyk and Volk in such a way that the residual meanings become of little consequence while allowing us to focus on the cumulative meanings of his life. In essence, I want to suggest that the proper name for this symbiosis is given to us in Van Wyk’s preferred tonality. But I will need to warm up before I get there and sketch the opening bars of that composition: a narrative of phylo-ontogenetic[5]Ontogeny charts the developmental stages of an individual; phylogeny, that of a collective society, culture, or civilization. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” was the answer to the question that haunted nineteenth-century biologists most, namely: what is the relationship between individual development (ontogeny) and the evolution of species and lineages (phylogeny)? For an extensive and critical study of the history of this idea, see Stephen Jay Gould’s unsurpassed Ontogeny and Phylogeny, Harvard University Press, 1985. synchronicity that, admittedly and like any other narrative, has its own frayed edges:

The life of the individual composer known as Arnold van Wyk is divided by his archivist and (auto)biographer Muller into “Juvenile” and “Mature”; a division which centres around the dates before and after Van Wyk’s stay in London. But this is a musicological distinction, made by an archivist. It doesn’t mean that either the man or his works were mature after London but only comparatively so, that is, relative to his pre-London scribbles. I return to this issue of classification later.

In similar vein, the musical life of the Volk is divided by Stegmann[6]Frits Stegmann, “Uit sy pen vloei musiek” in Acta Academica, Reeks B. No. 19, p25. into a “Juvenile” and “Mature” phase. The juvenile phase he refers to as the “Eerste Afrikaanse Musiekbeweging” and the more mature phase as the “Tweede Afrikaanse Musiekbeweging”.

These two sets of Juvenile/Mature are not unrelated; in fact, they are related if only at some distance. But the common ground on which they find each other is the longing of both subject and Subject to express itself in a way that would be recognised as mature (of course, measured by European standards). Stegmann articulates this synchronicity in a way that leaves one baffled and motionless for, if anything, this is a story of the Same, of perfect Likeness: “Om die plek wat [Van Wyk] in ons musieklewe inneem te besef, moet ons eie musiekgeskiedenis in gedagte gehou word” – a statement followed by the following elaboration:

“Die ‘Eerste Afrikaanse Musiekbeweging’, wat deur Stephen Eyssen ingelui is (na belangrike aanvoorwerk van ‘Jan Orrelis’ en andere), was byna uitsluitlik verbonde aan Afrikaans as sangtaal en het geen werke van internasionale gehalte opgelewer nie. Daarenteen het ons jonger komponiste ‘n nuwe weg ingeslaan en werke in alle vorme voortgebring – komposisies wat miskien nie volmaakte meesterstukke is nie, maar wat ten minste gunstig vergelyk met dié van die jonger komponiste in ander lande. In hierdie rypwording van ons musiek het Arnold van Wyk ‘n toonaangewende rol gespeel. Inderdaad is hy die eerste Suid-Afrikaanse komponis wat ook in die buiteland bekendheid verwerf het – en wat aan ons toonkuns status verleen het … Besonder treffend is die opregte wedersydse vriendskap wat tussen hom en Hubert du Plessis en Stefaans Grové ontstaan het. Laasgenoemde twee komponiste het intussen ook hulle belangrike bydrae gelewer tot die ‘Tweede Afrikaanse Musiekbeweging’, en albei lê ook buitengewone talent aan die dag” (my klem; p25-26; 29-20).

Here we have the germs of a more interesting circumscription of the nature of the symbiotic relationship between Van Wyk and the Volk: two mutually constitutive stories of maturation, phylogenetic (collective) and ontogenetic (individual) versions of the Bildungsroman (the “coming-of-age-story”) in which the collective yearning for maturity clears a space for the individual journey towards maturity which, in turn, will enable the collective yearning the expression of a maturity which … and so on and so on. Such reciprocity is alluded to in a review of a performance of Van Wyk’s second symphony (Sinfonia Ricercata) in July 1959 when it was noted that “… desondanks is [die slotfuga] ‘n oorspronklike, magtige, hedendaagse simbool waarin moontlikerwys ook, vanuit die Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns se gesigspunt, die kieme van ‘n nuwe Suid-Afrikaanse kultuur opgesluit lê” (I 710). But the reciprocity would reach its apparent apotheosis with the performance, on 14 October 1979, of Van Wyk’s Missa in illo Tempore which was commissioned by the town council of Stellenbosch in commemoration of the town’s tercentenary in 1979; a work many consider to be his most mature and memorable and which was recognised as such by a (by then) much more mature and appreciative audience. Stegman (45) comments about the Missa’s reception: “Daar was minstens een geleentheid toe [Van Wyk] moes besef het dat hy werklik tot sy volk deurgedring het en opreg waardeer word … Daarna het die gehoor spontaan opgestaan om met langdurige applous hulde aan ons voorste komponis te bring”. For Muller (III 210) the reason for this appreciative reception lies in the fact that the Missa “taps into an immemorial imagined past that provided continuity in the historical contingency of the nationalist Afrikaner myth”.

Only in the name of such orgiastic reciprocity or coincidence of the desire for “maturity” would it not matter – that is, not be anachronistic, inconsistent, contradictory or otherwise left unaccounted for – that a residue or excess remains: that the individual subject had considerable disdain for the (patriarchal, racist) politics of the Subject, or that the Subject could, through an act of sublimation, expel as Demonic the individual’s homosexual desire for Likeness while institutionalising its own homo-social desire for the Same under the name “Apartheid”. On the contrary, one could argue that this individual and collective desire for the Same, for perfect Likeness was the apotheosis of their symbiosis.

Interesting as this may be, it does not feel like the appropriate register in which to trace the cumulative meanings of Van Wyk’s large piano work, Nagmusiek. It would be more appropriate to do so in the register of his own preferred language, music. Clue to what this could entail is given to us in two concepts: “transposition” and “tonality”. As for transposition, Malan[7]Jacques P. Malan, “Arnold van Wyk in kultuurhistoriese perspektief”, in Acta Academica, Reeks B, No. 19, p12. comments about Van Wyk’s relationship to Afrikaner nationalism: “[hy het sy] nasionale verbondenheid met Suid-Afrika getransponeer na ‘n véraf, internasionale blikpunt wat tegelyk verteenwoordigend van vaderlandsintimiteit … is” (my klem). A relationship, then, marked by the distant and/but related. Tonality brings this “and/but” more sharply into focus: “In hierdie rypwording van ons musiek het Arnold van Wyk ‘n toonaangewende rol gespeel (emphasis added)”. Toonaangewend, inderdaad. Maar in watter tonaliteit?

II

Strydende tonaliteite

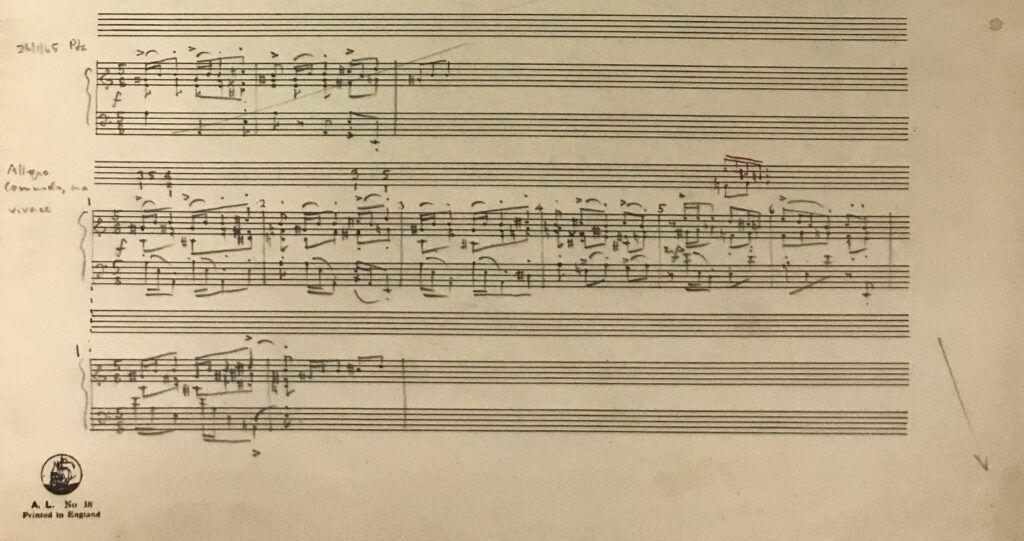

“Improvisation on a Given Theme“[8]Ontleen uit Muller I, 673: argief item 013, 4 Folios, bladsy 1-3: Improvisation on a Given Theme, Andante, C mineur, vir klavier, 44 mate, onvoltooid, blou ink.

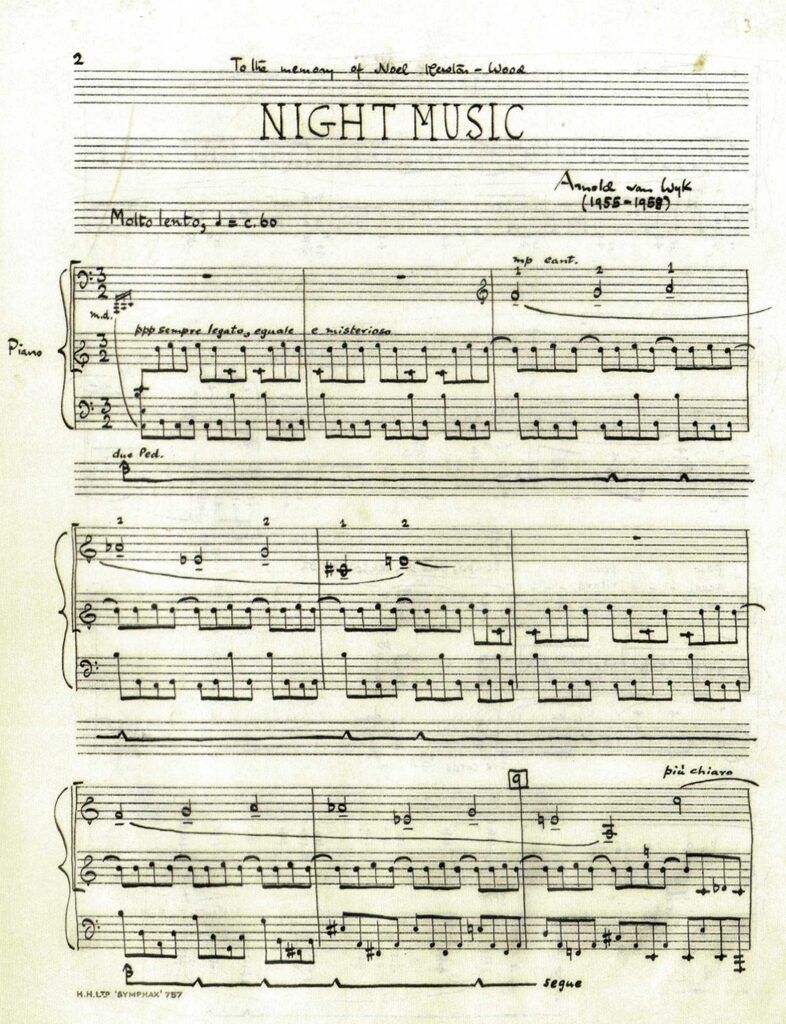

Nagmusiek exemplifies Van Wyk’s use of “conflicting tonalities” (“strydende tonaliteite”) or “distant but related tonalities” (“ver maar aanverwante tonaliteite”).[9]Closely related keys, in a traditional sense, are keys whose key signatures contain one sharp/flat more, or less than the other key (e.g. F major and Bb major: Bb major has one flat more than F major and these keys are therefore considered closely related). Therefore, the more additional sharps/flats we add to a key signature, in comparison to one with only a few sharps/flats, the more distantly related the keys will be (for example, C major and F# major will be considered distantly related). My gratitude to Altus Hendrick from the music department of the University of Pretoria School of Arts for this succinct explanation. Examples of two closely related keys are G major and D major (or G major and C major, or G major and E minor); two distantly related keys: G major and C# major; two very distantly related keys: B major and Bb major. The complexities of conflicting tonalities – which one reviewer commented sounds like a “theoretical hailstorm” (I 747) – do not need to concern us here. A short description by Van Wyk himself, drawn from two programme notes, and a brief comment from a reviewer will suffice for our purposes.

“Die komponis was destyds baie betrokke by wat hy ‘resulterende tonaliteit’ noem. Kort gestel, beteken dit die gebruik van baie ver verwante toonsoorte elkeen waarvan ‘gekleur’ word deur die tone van die ander” (I 745).

[“At the time the composer was very involved in what he referred to as ‘resulting tonality’. Formulated succinctly this means using very distantly related keys, each of which is ‘coloured by the tones of the other’ “].

“Die gebruik van ver-verwante tonaliteite is ‘n kenmerk van Van Wyk se styl. In die Sinfonia Ricercata is die ‘strydende’ tonaliteite F majeur vir die eerste deel en B-majeur vir die tweede. Maar Van Wyk se F majeur bevat B-suiwers en sy B-majeur F-suiwers. Dit is die gemeenskaplike grond waarop die teenstrydige toonsoorte mekaar uiteindelik vind” (I 709).

[“The use of very distantly related keys is characteristic of Van Wyk’s style. In the Sinfonia Ricercata the ‘conflicting’ keys are, in the first part, F major and, in the second part, B major. But Van Wyk’s F major contains B naturals and his B major, F naturals. It is the common ground upon which the contradictory keys eventually find one another”].

[“In hierdie werk wou ek] eksperimenteer met die teenoor- mekaarsteling van toonsoorte wat baie verlangs familie van mekaar is” (I 746).

[“In this work I wanted to] experiment with juxtaposing two keys that very distantly belong to the same family”].

“But its alien tonalities linked together are hard to digest at a first hearing and the major chord at the end was a relief”(I 709).

It seems, then, that the following can be abstracted as main characteristics of “conflicting tonality”:

The juxtapositioning of distantly related keys in such a way that each key borrows certain of the tone colours from the other which provides a “common ground” that is increasingly elaborated on until they eventually “find each other”.

But before we can proceed with using “conflicting tonalities” as key to unlock or decode aspects of Van Wyk’s life and our interpretation of it, we have to ask a second, preliminary question: why bother with such an expensive production (the Nagmusiek text consists of three beautifully bound volumes). What is the meaning of all this? After all, as Muller confesses, “Van Wyk se werke [het] met enkele uitsonderings ‘n heel beperkte resepsie gehad” (I 691). One would be forgiven for suggesting that the release of a new recording of Nagmusiek in 2020 comes at a time when we have a very complex and troubled relationship with Van Wyk the composer: he is close to but also distant from us; ver maar aanverwant. The conflicting tonality that characterizes his music also haunts our relationship with him and the mode in which we reflect about his life and music. For instance, should I write this little programme note in Afrikaans or English? Measured by European standards, cosmopolitan Afrikaners of Van Wyk’s generation were equally fluent in both languages. Bilingualism was not a tension, ambivalence or even a choice to contain but simply something ordinary people (of a certain class) did as a matter of fact, balancing, playing with two languages considered, in their minds, “ver maar aanverwant”. “Hoe het Acáma Fick nou weer na [Van Wyk] verwys toe ons eendag net kortliks langs mekaar beland het by die rekenaarterminale in die biblioteek? ‘ ’n Afrikaner ja, maar [Van Wyk] was veral ‘n Engelse gentleman, aristokraties selfs’ ” (I 53). It seems appropriate, then, to compose this little programme note by not choosing one language over another but by allowing one to be coloured by the tones of the other.

It is evident that I am not the only one to grapple with the difficulty of what it means to curate the legacy of a relatively obscure Afrikaner composer of a small white elite. Muller continues his reflection on the relevance of Van Wyk by stating at the beginning of his (auto)biography what it means to engage Van Wyk today: as archivist, as ethnomusicologist, as distant admirer. Aan die een kant is daar, merk hy op (I 611) mense wat sou argumenteer dat Van Wyk “so ‘n seminale en belangrike figuur [is] dat sy nalatenskap meer as net nog ‘n versameling is en dus spesiale aandag verg”. Maar, skryf hy verder, aan die ander kant, “as die veralgemening gewaag kan word dat die man op die straat nie weet wie Van Wyk is of hoe sy musiek klink nie, kan die stelling ook gewaag word dat die opkomende middelklas en intelligentsia in Suid-Afrika in die afsienbare toekoms nie sal belangstel om te vra nie” (I 611-612). En laastens, “Internasionaal is dit net ‘n klein groepie ouer musici en akademici, hoofsaaklik in Engeland, wat nog die naam herken” (III 10).

Watter stelling of aanname is waar, of sal ek sê, watter een is meer realisties? Dis waarskynlik nader aan die waarheid om te sê dat beide hierdie evaluarings waar is; dat alhoewel die twee posisies ver van mekaar skyn te wees, hulle tog op ‘n manier ook aanverwant is; ‘n disonansie wat mens kan opsom deur te sê: dat Van Wyk vir “ons” belangrik is, beteken nie dat hy insigself belangrik hoef te wees nie; of andersom: omdat hy nie insigself belangrik is nie, beteken dit nie dat hy nie vir ons belangrik gehou kan word nie. Die problem hier is natuurlik die idee dat iets of iemand “insigself” belangrik kan wees. Is enige kunstenaar insigself belangrik: insigself en vir sigself? Of is daar maar net die meedoënlose politiek en partydigheid van die daad van kanonisering? Is dit nie maar net die kanon wat nie net die belang nie maar inderdaad ook die betekenis van ‘n kunswerk en ‘n nalatenskap bepaal? Inderdaad. Die idee van die kanon en die daad van kanonisering is een van die sentrale temas van geskiedskrywing. Wie se kanon? Kanonisering met watter doel voor oë? Wie besluit wat word in- en wat word uitgesluit? Deur van meet af aan hierdie vrae op die voorgrond te stel forseer Muller se Nagmusiek ‘n mens as ‘t ware in ‘n baie komplekse verhouding met melankolie: aan die een kant, soos die skrywer self erken, handel dit nie hier oor iets (die komposisie Nagmusiek) of iemand (Van Wyk die komponis) wat ons regtig mis nie. Gevolglik is daar niks om oor treurig of melankolies te wees nie. Aan die ander kant kan die sorg waarmee Muller Van Wyk se lewe ver-haal en agterhaal nie anders nie as om ‘n karakter te skep wat die leser wens hy kon mis. Hierdie hunkering daarna om iets te kon mis is die komplekse ervaring van melankolie: ‘n meta-melankolie; ‘n melankoliese hunkering na die ervaring van melankolie. En alhoewel van Wyk nie die objek of subjek van hierdie meta-melakolie is nie, is hy tog op ‘n indirekte manier die oorsprong daarvan. Die “subjek van melankolie” en “die oorsprong van melankolie”, alhoewel twee verskillende dinge, is dan tog ná verwant aanmekaar, of ver maar aanverwant. Die gedeelde grond tussen “subjek van melankolie” en “oorsprong van melankolie” is nie die historiese persoon Van Wyk nie, maar Van Wyk as Idee, sodat mens kan sê die Van-Wyk-Idee is die subjek van ons meta-melankolie wat deur die daad van herinnering, en presies dansky die vergetelheid waarin Van Wyk versink het, her-skep kan word.

Hierdie projek is inderdaad ‘n daad van kanonisering[10]This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author., ‘n gebaar van die opsteller daarvan en die befondsers en institutionele ondersteuners daarvan wat sê: “Deur die omvang van hierdie arbeid konstateer ons Arnold van Wyk se belang vir al ons mense, en die unieke bydrae wat hy gelewer het om ons posisie en menswees in Suid-Afrika uit te sê in die medium van klank. In hierde opsig is dit dus ‘n duidelik ideologiese projek wat deur die gewig en omvang daarvan kanonisering opeis” (I 612).

Op ‘n vreemdsoortige manier word Van Wyk dus van belang deur die spanning tussen die vergetelheid en (on)verwantskap met hom as doelbewuste daad van kanonisering en herskepping aan te bied. Die dominante “Van Wyk is vergete” en die subdominante “Dis die moeite werd om hom te onthou” word opgelos deur ‘n self-bewuste en self-refleksiewe daad van kanonisering. In watter sin is dit dan, soos die argivaris erken, steeds ‘n ideologiese projek? Is ‘n ideologie wat sigself as sulks herken, sigself konstateer as ideologie, steeds ‘n ideologie? Daaroor kan mens natuurlik stry todat die perde horings kry. Punt is, die daad van kanonisering is onvermydelik; die effek daarvan is altyd berekenbaar in die sin dat dit ‘n onderskeid skep (wat voorheen nie bestaan het nie) tussen wat voortaan onthou/vergeet gaan word as, óf ver, óf aanverwant. Muller se projek is verwant aan die ideologiese maar, danksy die self-bewustheid daarvan as ideologiese projek, voldoende ver verwyder daarvan dat ‘n mens kan asem skep en weer na Nagmusiek wil luister. In Deel V keer ek terug na hierdie kwessie van die argief en sy ontbinding en herbinding. Vir die oomblik berus ek my in die wete dat om doelbewus te kanoniseer, wetende dat dit ’n nodige dog problematiese daad is, is in ‘n sekere sin niks anders nie as om te improviser op ‘n gegewe tema.

III

“Dood”

Classification; transcription; signatures.

“The other themes for this Trio will be found in my kas“.[11] From Muller I 20. Title borrowed from archive number 21 ‘Manuskripboek’, 30.

As I’ve mentioned, the catalogue and worklist of Arnold van Wyk’s music from 1925-1983, so meticulously compiled by Muller, distinguishes between his “Juvenilia” (1925-1938) and his “Mature Work” (1938-1983). For a musicologist who must proceed as a taxonomist in order to show discontinuities in the developmental phases of the composer’s life as composer this is a useful and it would seem, quite natural, distinction. But the distinction cannot but trouble the commentator who is interested in exploring the meanings that cumulated in the production of a work, particularly when that work is considered his most, or one of his two most, important works. In this case continuities are more important than discontinuities.

Three markers are invoked by Muller to demarcate the difference between the Juvenile and Mature. Artistic: with rare exception, compositions dating from the first 23 years of Van Wyk’s life were noted in manuscript books, sometimes only by way of sketches. After his return from England his approach is undeniably more complicated and compositions and sketches are made on manuscript paper; geography: “Works that were composed before he departed for England are listed here under Juvenile while works that originated during his stay in England, appear in the second worklist as representative of his Mature work” (I 615); autobiographical: before he departed Van Wyk commented to his friend Nicol Viljoen that departing for England meant leaving behind the trifling concerns of the past.

But the distinctions invoked to map out this geography of increasing maturity are troubled by works that are undecidable and markers that, although distantly related to one another (South Africa and England for instance), borrow sufficient tonality from each other to suggest a reproductive sense of continuity. Consider Vier weemoedige liedjies, composed between 1934 and 1938 but revised in 1947 and now generally considered to mark the beginning of Van Wyk’s mature phase. Or take the very distinction between “juvenile” and “mature” and the spectre that haunts maturity in the form of the “infantile”. Generally, “juvenile” simply refers to that which belongs to, in the sense of being representative of, what it means to be young. Of course, the adjective can slide into the pejorative – “I’m tired of his juvenile company” – but even that is more a slight than an insult; a comment suggesting the unhappy a-synchronicity or “out of jointness” of two people’s expectations. Infantile, on the other hand, has the general connotation of a regression to infancy; to that which preceded the current stage of emotion or physical maturity.

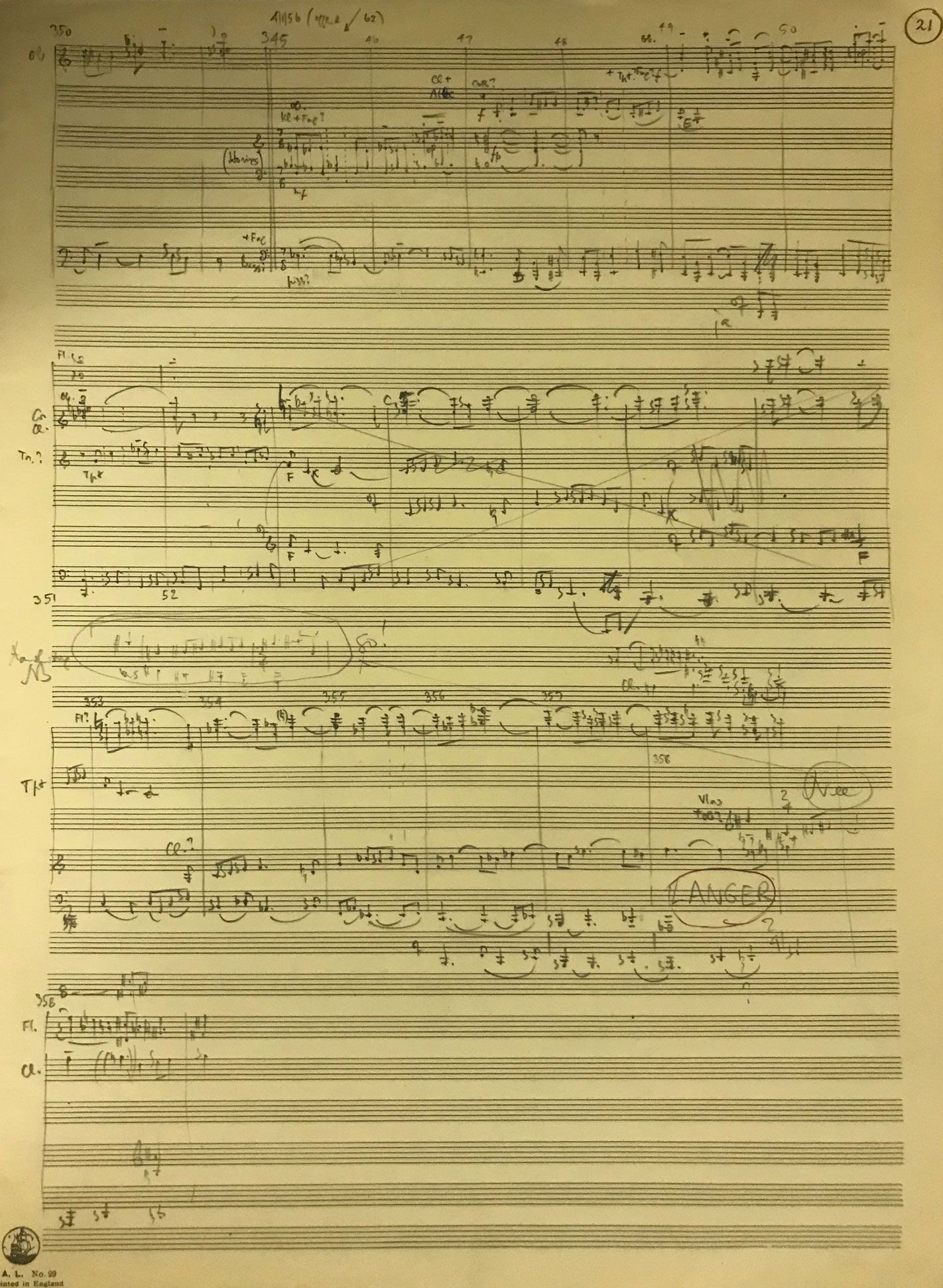

First marker of indistinction: masturbation. Conventionally understood, masturbation is associated with the juvenile (although, of course, as an act of self-love it continues into old age). That said, the mature Van Wyk’s habit of obsessively noting every repetition of the act, transcribing its occurrence and the deed into notation, symbolically encrypted on his manuscript books almost 10 years after the composition of Nagmusiek, troubles the distinction between juvenile and mature and testifies to a tension between the juvenile/mature and the spectre of the infantile. An extract from the notations of his masturbation record in 1967 – a full table of which appears in Nagmusiek (III 76) shows, in the first column, the date; in the second, an arrow the meaning of which has remained undeciphered by his (auto)biographer, and in the third and last column, a comment about the time of day, the object of his phantasy and so on.

Second marker of indistinction: transcription; imitation; signature. The tension between the distant but related keys of the juvenile and the mature is sign of another continuity that intrigues, namely Van Wyk’s fascination with writing (letters, not notes), the signature, and acts of transcription – not from one instrument to another but from one mode of expression (language/music) into another (music/language) as well as the codification of stories into sounds and names into notes – “die vermoë om poësie te verklank” (II 569). For van Wyk, music and writing were two distant but related modes of expression. By his own admission, had he not become a composer he would have become a writer – which means that it makes perfect sense to transcribe Nagmusiek (the music) into Nagmusiek (the interwoven narrative of three lives: Van Wyk, Werner Ansbach and Stephanus Muller). Nagmusiek (the text) is in that sense the apotheosis of Nagmusiek (the composition), the coming-to-fruition of a mode of expression that Van Wyk chose not to pursue. I return to this apotheosis below. For the moment I just note the juvenile signs of this common ground between writing and composition in the life of Van Wyk; signs of indistinction, a taxonomy of which will distinguish between:

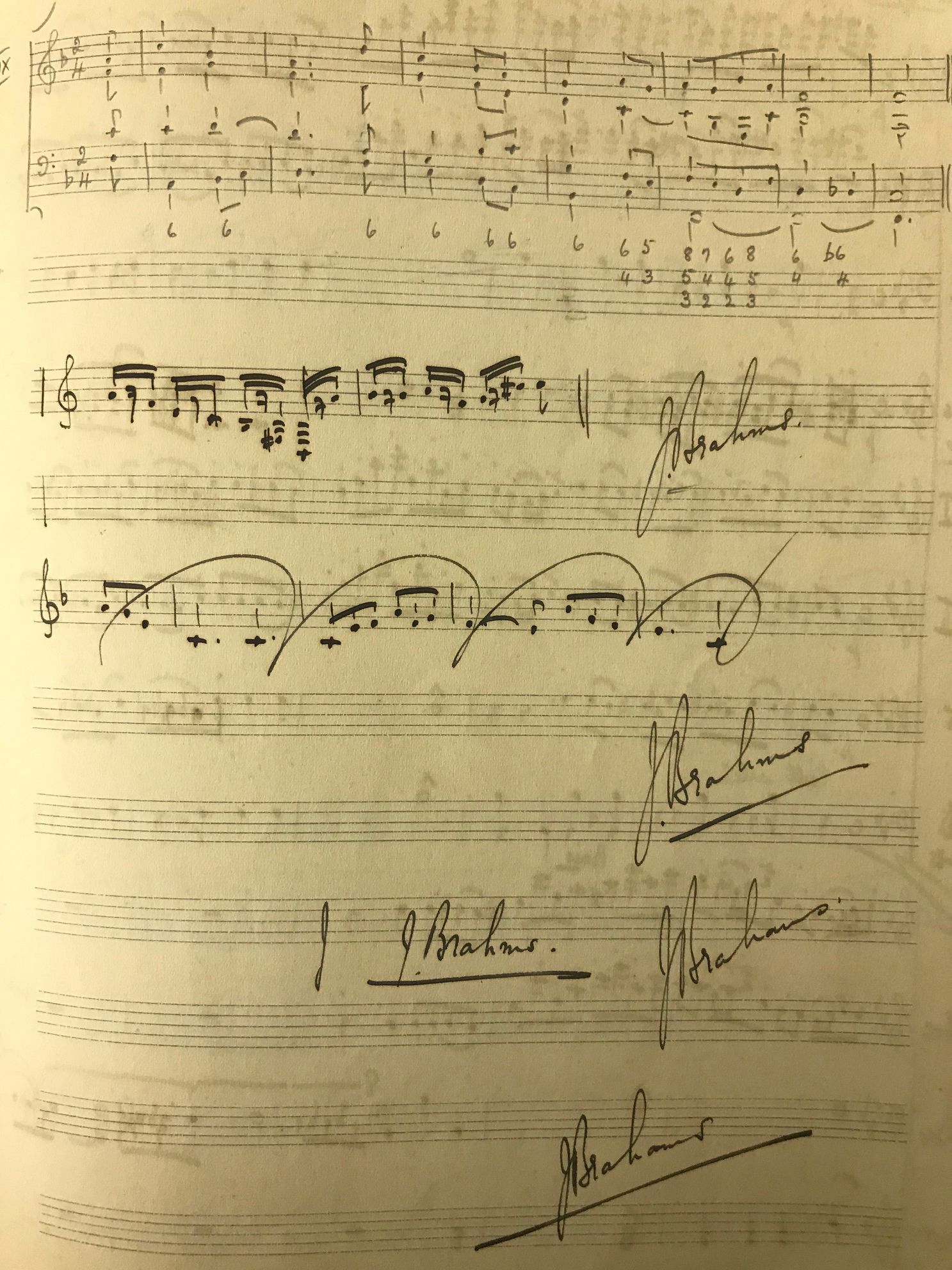

Iterations of the signature: Van Wyk placing his signature on the cover of the juvenile manuscripts even though many of them only contain a couple of bars, fragments of sketches of themes and so on: a juvenile rehearsal of maturity-to-come. Is it not true that boys start practicing their signature at the precise moment when they start imaging themselves as grown men with responsibilities, authority; to declare, but also to assert: I am here; I was here; presence through the iteration and repetition of the constative (which is also a performative and a performance of existence), and which in at least one instance (I 623) sees him repeating his signature on the cover of a manuscript book three times.

Here a question arises that must remain unexplored: what is the relationship between repetition and death, and between repetition and melancholia apart from Freud’s insight that Wiederholungszwang or the compulsion to repeat is related to the death drive and in that sense a rehearsal of death?

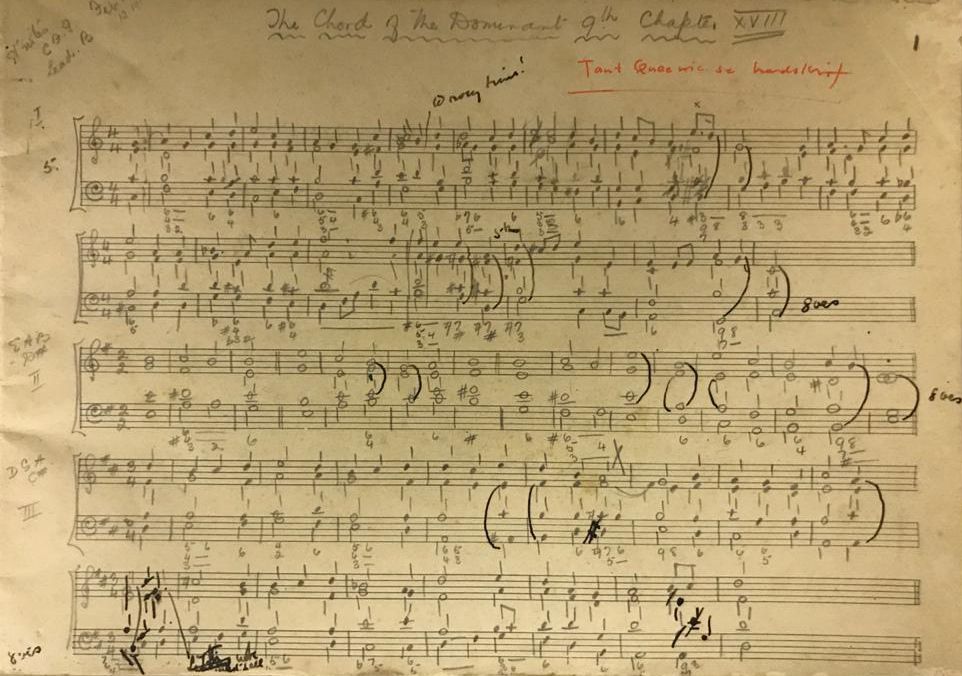

Imitation: the signature of other composers – such as Brahms (I 621):or the imitation of the handwriting of others (I 621) in his own handwriting: “Sus Mien se handskrif” or elsewhere (632) “In Van Wyk se handskrif in rooi ink: ‘Tant Queenie se handskrif’ “.

Imitation is a central theme in Van Wyk’s life. In a 1981 interview he recalls how he started composing (until then he had been quite happy to play by ear and couldn’t see the point of writing and composing, of notation): “I remember very vividly that I started writing down things out of pure envy. I envied the other people who were making beautiful things and I thought why shouldn’t I do it as well” (II 528). The Afrikaans somehow resonates more deeply: “En ek onthou baie goed hoe dit gekom het dat ek uiteindelik iets probeer neerskryf het. Ek het dit gedoen, nie omdat ek wou komponeer nie, maar doodeenvoudig omdat ek jaloers en afgunstig was” (III 42). Envy is “resolved” through imitation, we know that much. But what is the envy for and of? Van Wyk understood it as the desire which we recognize as mimetic: to “also make beautiful things” which is not the desire for the thing in itself (composition) but the desire to have what others have; to be able to do what they do. Composition as a derivative desire for something else. But what? What is the envy and act of imitation after? What does it really want? Girard[12]Violence and the Sacred (1995:146) René Girard. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. would say: the plenitude of being:

“Once his basic needs are satisfied (indeed, sometimes even before), man is subject to intense desires, though he may not know precisely for what. The reason is that he desires being, something he himself lacks and which some other person seems to possess. The subject thus looks to that other person to inform him of what he should desire in order to acquire that being. If the model, who is apparently already endowed with superior being, desires some object, that object must surely be capable of conferring an even greater plenitude of being” [emphasis added].

Imitation, or the mimetic desire for plentitude, is a theme that emerges early in Van Wyk’s life; an Aria that would recur in many Variations through-out his life thus constituting an important accumulated meaning of his life. About this continued imitation of signatures Du Plessis[13]Hubert du Plessis, “Arnold – aanhef, aandenkings en anekdotes”, in Acta Academica, Reeks B, No. 19, p39. comments: “Sommige van die briewe se koeverte is in sy normale, pragtige handskrif geadresseer; ander in ‘n gemaakte skrif. Hy kon die naamtekenings van groot komponiste baie goed naboots. Had hy misdadige neigings, sou hy tjeks kon vervals!”. There is seamless continuity between, on the one hand, this fascination with the signature – his, and those of composers whom he considered mimetic models of plenitude (Brahms, “voorbeelde van Beethoven se handskrif”, I 531), the perfect imitation of the score of Satie’s 3rd Gymnopédie (Du Plessis, 39) and, on the other hand, mimetic acts of impersonation, the need to be the centre of attention at parties – to, in the words of Girard, be the one who embodies the very plenitude of being; a plenitude in which levity and melancholy are but flip-sides of the same coin (II 536-537).

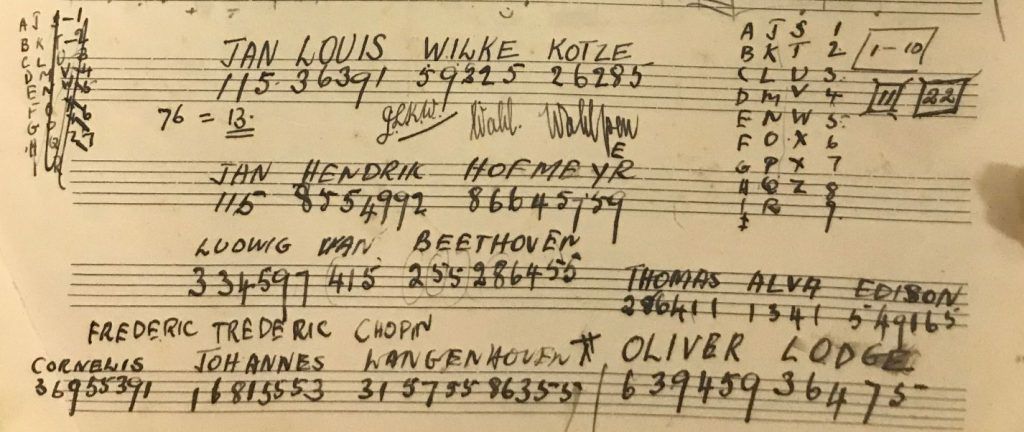

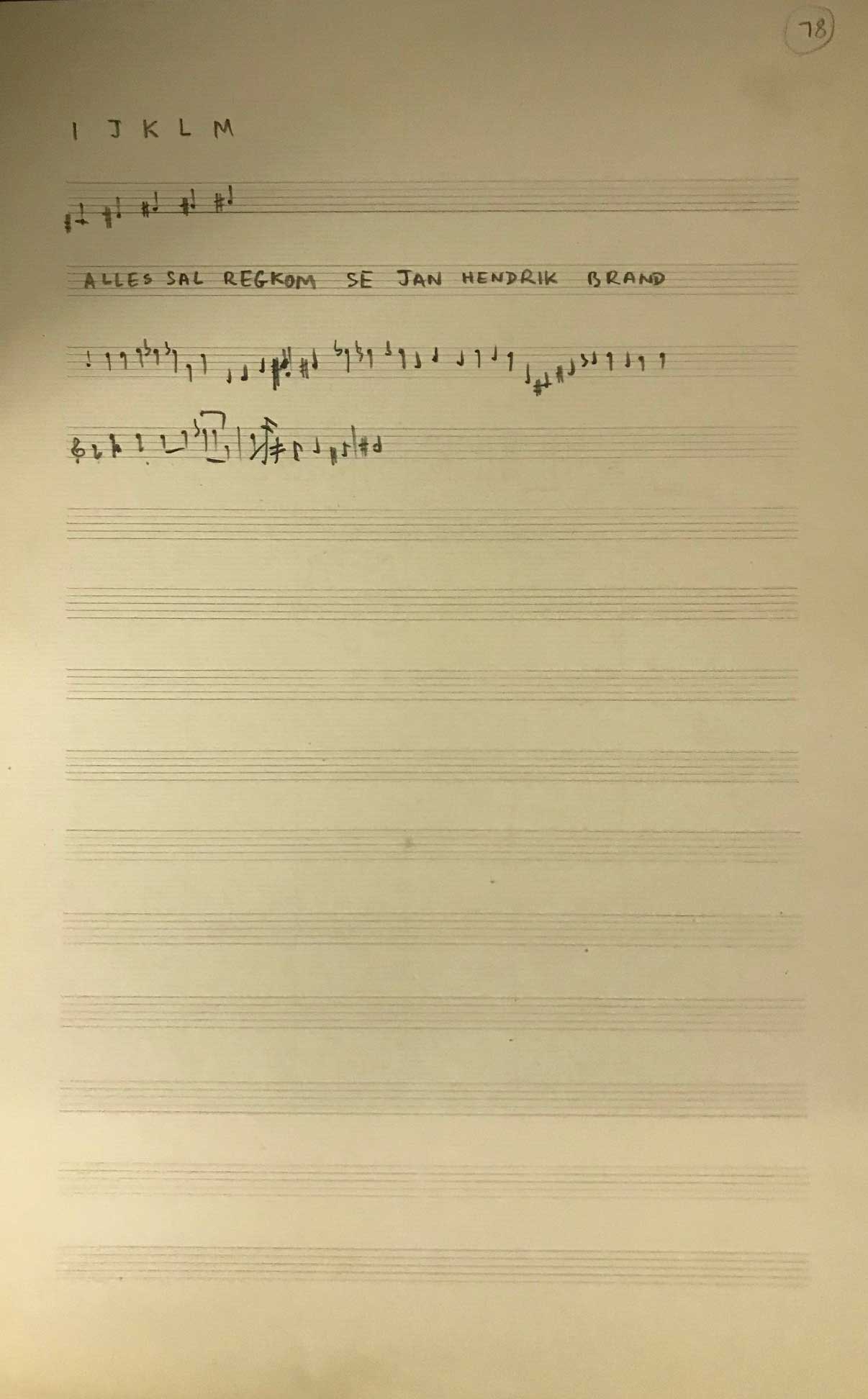

Transcription: of names – musicians, authors – into numbers (I 628): “onderaan die stuk is ‘n kodestel in swart ink waarvolgens name in syfers omskep is. Die name is Jan Wilke, Louis Kotze, Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr, Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin, Thomas Alva Edison, Oliver Lodge, Cornelius Johannes Langenhoven”.

What is the point of this generative questioning of the difference between juvenile and mature, of emphasizing continuities over discontinuities? Perhaps simply this: it allows us to trace cumulative meanings in order to use them as key to unlock what death, sleep and beauty – that unholy trinity and sign of the melancholy soul which inspired Nagmusiek – meant to Van Wyk.

IV

“Slaap”

Nagmusiek: or: the apotheosis of (auto)biography.

‘[D]econstruction. There it is. I’ve used the word.’[14]From Leonhard Praeg, ‘Notes on/of Arnold van Wyk’s Nagmusiek: A Melancholy Anatomy.

To transcription, imitation, and signature we should add “codification” by which I mean not the transcription of notation for one instrument into that of another but the translation into “code”: the codification of acts of masturbation into signs; or encoding letters into figures (I 639):

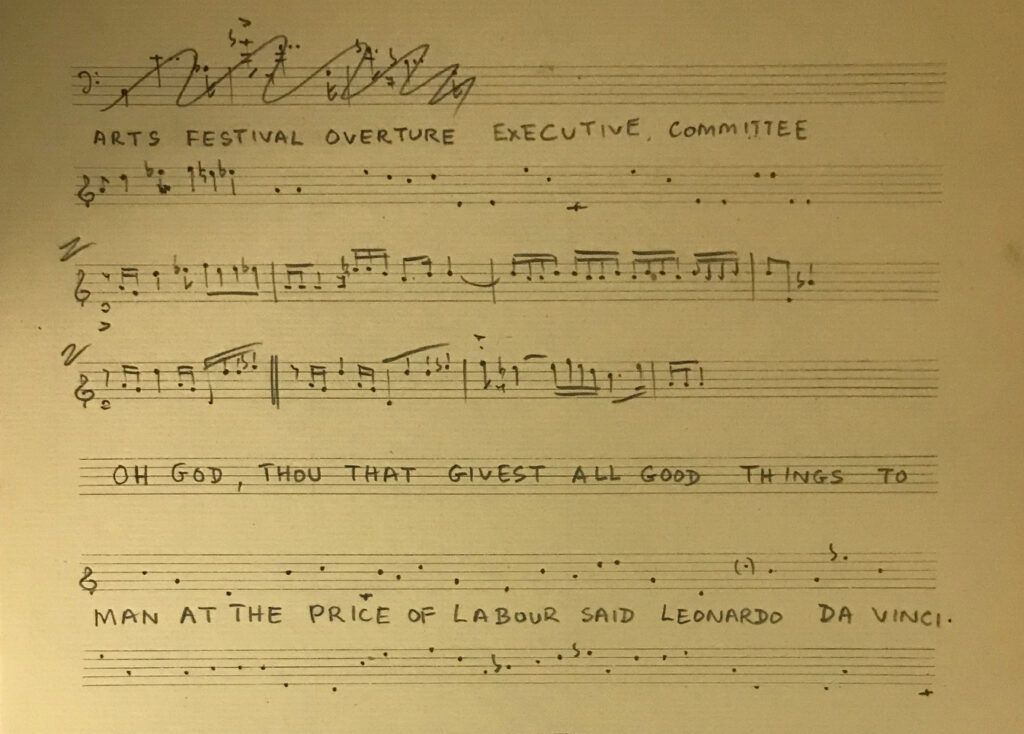

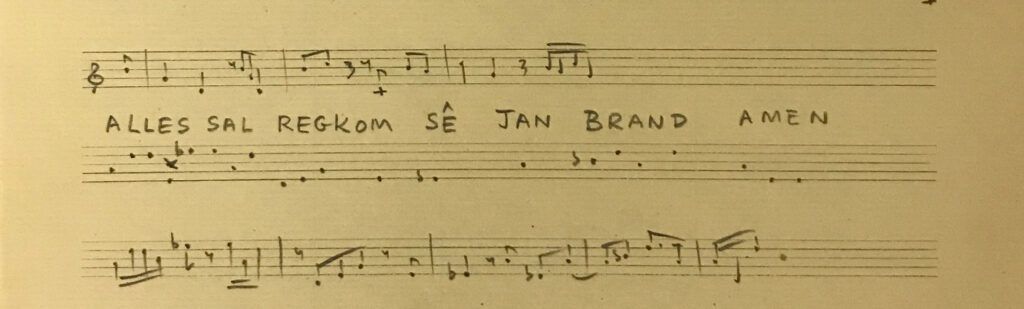

” ‘The dancing men this helps me but little. I cannot read your intentions’ in die gekodifiseerde alfabet” – a codification but also the codification of phrases into music notation: examples of which include the phrases “Arts Festival Overture Executive Committee”; “Oh God, Thou that givest all good things to man at the price of labour said Leonardo da Vinci” and “Alles sal regkom sê Jan Brand Amen” (I 707), “Universiteit van Suid-Afrika eksamenstukke” (I 772), and “prelude for advanced division or grade” (I 772), “Dachau Auschwitz Buchenwald”, “swart met ‘n tikkie wit en effense groen?” and so on.

Heel vroeg in sy “dik boek” (I 23) Nagmusiek, vra Muller “Hoe bring mens geskrewe hulde by ‘n lewendige musiek-beoefening uit en, watter sort navorsingbenadering kan kontekstualiteit ten opsigte van Van Wyk se werk verseker?”. Dis ‘n vraag wat in hierdie programnota nou al ‘n amper herhalende vorm aanneem, naamlik wat is die verhouding tussen taal en musiek, die vertaling, in woorde, van musiek, die notering van poësie en die transkripsie en kodifisering van een medium in ‘n ander wat hierbo bespreek is as een van die deurlopende temas in Van Wyk se lewe en wat die onderskeid tussen juvenilia en volwassenheid bevraagteken deur die klem op kontinuïteit te plaas. Muller’s uncertainty is in a sense no more than an expression of an archē or originary undecidability in the life of Van Wyk himself: “Arnold het graag geskryf (nie gekomponeer nie) en het ook baie geskryf. Hy het skynbaar eenkeer vir Nicol Viljoen vertel dat as hy nie ‘n komponis geword het nie, hy ‘n skrywer sou word” (I 69). I take Muller’s Nagmusiek, then, to be the apotheosis of Van Wyk’s Nagmusiek: the codification of love, sleep and death into what, in another life, may as well have been its original expression, namely Nagmusiek as written text.

But there is another reason for considering the second Nagmusiek the apotheosis of the first. At a deeper level, the subject Van Wyk and author Muller, however distant they may be from one another in time and place, are related through their shared fascination with what Van Wyk explored in composing Nagmusiek: love, sleep and death – to which I want to add: solitude, restlessness and a certain resistance to the possibility that sex, love and intimacy may coincide. The overwhelming sense one gets on reading Muller’s Nagmusiek is of brooding melancholy. At its origin lies the melancholy of a composer who spent his life fascinated by love, sleep and death (solitude, restlessness and the rest of it) – so much so, that one can say of Van Wyk-the-Idea and subject (as presented by Muller) what the subject Van Wyk said about Nagmusiek:

“Ek is dus huiwerig en teësinnig as ek sê dat dit my bedoeling was om in [Nagmusiek] ‘n omvattende skildering van die nag te gee, van sy skoonheid, sy geheimsinnigheid, sy onheilspellendheid; om sy halfgehoorde klanke weer te gee en die nag te toon as the ewebeeld van liefde, slaap en die dood. Beskou die werk maar as in essensie elegies – ‘n groot treurlied”.

Layered over the original melancholy and its transcription (or is it codification?) in the composition Nagmusiek, is a further codification (or is it transcription?) of melancholy in Nagmusiek as text; a text whose status is that of a third iteration of melancholy in a chain of transcriptions: from an originary experience of melancholy to its inscription in music to its codification as text. In that precise sense, the text becomes the apotheosis of the originary experience of melancholy, a deferential reverie. Let Nagmusiek = Nagmusiek (a “large book”, writes Kaganof, and I cannot but be reminded of Laurie Anderson’s Let x=x[15]This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. , ‘You know, I could write a book/And this book would be thick enough to stun an ox’). Yes, a wilful association, one that just forced itself on me as I reread this paragraph – in much the same way in which we must assume that abomination of sentimentality, Eine Kleine Nachtmusiek, in all its silliness and frivolity, penetrated against his will Van Wyk’s consciousness as he contemplated a title for what would be named Nagmusiek.

Let x=x

V

“Liefde”

‘Archive fever’

“A one-night stand is a brush with the divine”[16]Margaret.

There are two accounts of sexual encounters in Muller’s Nagmusiek that circumscribe the meaning of the experience of the melancholy trinity of love, sleep and death of which the text is the apotheosis. Both encounters present as instances of de-differentiation; of differences that unravel in order to reconfigure the difference between self and other, lecturer and student, sameness and difference, daemonic and divine. In Violence and the Sacred Girard argues that every social order (considered a system of differences or Degree) is founded through, and thereafter sustained by, sacrificial acts of violence. The unifying force of founding acts of genocide or massacre at the origin of a culture or society are perpetually iterated through similar acts. For instance, wars are often declared and waged in the build-up to elections because nothing unifies an electorate better than a common enemy. But the war itself is nothing but the iteration of the founding civil war, genocide or massacre that originally unified a disparate collection of people or tribes into an electorate or community. Such sacrificial acts of scapegoating sustain society conceived as a system of differences or Degree, an order of things. But it often happens that the sacrificial mechanism stops working: there is no enemy at hand; no plausible accusation can be fabricated, or the very logic of sacrificial violence has become transparent for what it is: a performance devised to sustain a system of Degree. When this happens, the whole lot starts unravelling or de-differentiating until either the system collapses or succeeds in reviving itself, once again, through another, different act of founding violence.

The relationship between teacher and pupil or between lecturer and student is one of the most fundamental in any society because it inculcates in the next generation the differences (gender, moral, intellectual, religious, spiritual) that constitute a society; the differences that a society holds dear because they define its sense of identity. Consequently, the de-differentiation of the teacher/pupil and lecturer/student relationship is a perfect synecdoche for what Girard calls a crisis of de-differentiation or a Crisis of Degree; a crisis that presents as a downward spiral of de-differentiation followed by an upward spiral of re-differentiation (if a successful act as sacrificial scapegoating can again be performed).

The two sexual encounters in Mullers’ Nagmusiek are precisely that, synecdoche of the Volk’s de-differentiation and, to some extent, re-differentiation. The two students in the respective incidents are no longer the “goeie Afrikaner kinders wat hulle Ooms en Tannies respekteer”. They are sexual predators who don’t care much for the difference between student and lecturer or for the values that used to be inculcated when the difference was sacrosanct. What they represent – the precise opposite of love, sleep and death, namely lust, hyper alertness and virility – explodes the archive and restores to it the feverishness that always accompanies any contestation of what should be included and excluded. First, there is Cecile, a young female student, who seduces the (auto)biographer into an act of urolagnia in his office:

“Sy neem my kop tussen haar hande en druk dit hard teen haar onderlyf. Terwyl ek die posisie van my knieë verander om nie om te val nie, voel ek hoe die glas deur my vel sny. Ek gryp haar bobene met albei hande om my balans te behou. En toe ruik ek dit, voor ek dit hoor of voel. Die warm vloeistof wat deur die dun material syg, wat teen haar bene aflooop en met die water en bloed op die grond meng. My wang is nat … Ek proe haar en voel hoe ek kom terwyl my mond soek. Dieper, meer.”

But it is the second encounter with a young male student that is more relevant for this melancholy anatomy of Nagmusiek, and that for two reasons: one, because of its carefully constructed symbolism and two, because it takes us back to the phylo-ontogenetic narrative I introduced at the beginning of this piece. As far as the matryoshka of symbolism is concerned, both sexual encounters take place in Stellenbosch, the historical bastion of Afrikanerdom and a town we first encountered at the beginning of this programme note as scene of an orgiastic symbiosis between a mature Van Wyk and a mature and appreciative Afrikaner audience; nested in this town is a smaller bastion, the male hostel Dagbreek, and nested in the hostel, its archive. Symbolically, then, the hostel archive is the sancta sanctorum of the Volk and it is to this archive that our intrepid (auto)biographer turns to trace evidence of Van Wyk’s stay there as a student between 1936-1938. Arriving at Dagbreek he is introduced to the hostel’s archivist Spuities who will show him the collection. One archivist meets another, something strange and unsettling that leaves one baffled and motionless: the Same, the perfect Likeness. The momentum of de-differentiation is set in motion as Spuities addresses the author, not as the patriarchal “Oom”, but the post-patriarchal “Meneer” – which later further de-differentiates into the informal personal pronoun “jy” (at which point both archivists already seem to be in-different to difference).

“Toe die donker deure oopswaai, is die eerste ding wat my aandag trek die vergeelde olifanttand wat van die dak afhang. Geskenk deur Sy Edele advokaat B.J. Vorster … Toe sien ek die groot Verwoerd-uitstalling. ‘Was Vorster hier? En Verwoerd?”

” ‘Ja, dit was altyd die groot ding van Dagbreek. Vorster en Verwoerd. Nou het dit ons ‘n bietjie in die gat kom byt. Maar hy wás ‘n groot man’. ‘n Hand word ferm neergesit op ‘n foto van Verwoerd waarop staan ‘Die grootste Dagbreker’ …

“Verduidelik nou maar net vir my waar ek miskien iets kan kry en dan kan jy maar weer jou gang gaan. Ek kan sien jy is besig. Ek sal jou kom roep wanneer ek klaar is.”

“Die ding is, ek het nou net oorgeneem as argivaris. Jy sal maar moet kyk.”

“Ek hou van Spuities. Mooi seun. Hy noem my nie ‘oom’ nie …”

“Ek ruik sy sweet toe hy in die stoel langs my tafel kom sit. Hy lyk nie haastig nie …”

” ‘Ek hou van musiek’. Hy leun wydsbeen terug in die stoel. Hy het nie ‘n onderbroek aan nie. Hy kan sien ek staar. ‘Ek hou van mans wat hou van musiek’. Hy kyk ongeërg na die uitstallings.”

“Ek kan uitloop, maar ek bly staan. Wag. Spuities se bolyf is nat, gespierd, gesond …”

“Skielik leun hy vorentoe. ‘Wat dink jy?’”

“Ek maak my oë toe.”

“Hy glimlag, staan op, neem berekend my hand, plaas dit op sy harde knop met sy een hand bo-op …”

“Ek prober nie my hand terugtrek nie.”

“Hy staan teen my, praat skorsag in my oor, sy ander hand agter my kop. Ek voel sy baard, ek ruik sy asem. ‘Ek gaan my piel, die dik piel wat jy so lekker bevoel, in jou opdruk en jou naai in daardie ongebruikte tonnel…”

“Toe hy my neergooi op die vloer, voel ek hoe die glas se sny op my knie skerp pyn. My wêreld kantel. Stadig, ritmies, brutaal, meedoënloos. Ek tol stadig, gewigloos na ‘n tyd en plek weg van die kamertjie waarin die jong man hortend op my afdruk. Maar soos ek weggly, bewonder ek die krag in die hand wat my mond toedruk in ‘n greep wat my nek terugtrek, verlustig ek my in die magteloosheid, huil ek geluidloos van verrukking” (I 151-154).

At the moment of a collective downward spiral of de-differentiation – say, when our racist Degree of Afrikaner nationalism de-differentiated in order to re-differentiate as democratic nationalism (a re-differentiation celebrated across the world for having managed to re-invent Degree not through sacrificial violence (civil war) but through reconciliation and forgiveness) – at the moment of the downward spiral, the Old patriarchal myth always has a hard time avoiding getting fucked in every conceivable orifice that can be said to represent the body politic: the anus, the eyes, the ears, the mouth, the vagina. The Old South African flag and national anthem have had a particularly hard time of it: in two separate productions at the Grahamstown National Arts Festival Gavin Krastin, in a work titled Nil,[17] This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. pulled the flag from his anus and in Inkukhu Ibeke Iqanda Chuma Sopotela pulled it from her vagina, while Steven Cohen’s The Cradle of Humankind[18] This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. featured footage of a giant fish-mouthing anus singing Die Stem.

Interesting about the way Nagmusiek presents the visceral experience of de-differentiation in Dagbreek is the eroticized and sexually arousing de-differentiation of student and lecturer and of rape and sex that pivots around the common denominator of Sameness: two archivists of the patriarchal Afrikaner legacy having anal sex under the benevolent gaze of Vorster and Verwoerd, the Ground Zero of which is the (auto)biographer’s ecstasy (“verrukking”). That ecstasy is the Ground Zero of the writer’s journey, of his memory of what being Afrikaner means and, in a very real sense, also the Ground Zero of the collective Afrikaner memory de-differentiated into its worst nightmare: the mere homo-social desire for Sameness which was sublimated as “Apartheid” is made viscerally concrete as homosexual anal sex. If in this programme note the story of Van Wyk started with an aspirational symbiosis between his and the Afrikaner’s desire for maturity, an upwards spiral towards greatness and immortality, then the scene in the Dagbreek archive is the obverse: the devolution of the collective archive and its amanuensis, Muller/Ansbach, down the abyss of nothingness.

But the ecstasy is also Ground Zero for the melancholy trinity of love, sleep and death that lies at the origin of Nagmusiek because it is from this sancta sanctorum that a whole set of difference will be reconstituted, both for the author as individual as well as the text that self-consciously presents itself as active site for the reconstruction and reconfiguration of collective memory. In light of Van Wyk’s penchant for codifying his ecstasy in a table – of which I inserted an extract above – I feel compelled to codify the (auto)biographer’s ecstatic experiences in a similar fashion, if only because the two “codifications” represent important aspects of the meaning that made possible both Nagmusiek as composition and Nagmusiek as text.

The nested symbolism of the Dagbreek encounter makes it difficult not to recognize that we find ourselves in the domain of deconstruction. There it is. I’ve used the word. And yet, knowing that does not make the scene less sexually arousing. Why not? I think because this crucible of de-differentiation confronts us with our deepest longing, a longing we re-enact through every act of repetition (of signatures, performance, transcriptions); a longing the wise demigod Silenus recognized as the longing not to have been born, not to be, to be nothing; or, as a second best, to die soon. But it is also from this crucible – where we find, fused together, excruciating ecstasy, the longing for eternal sleep and the wish always to have been dead – that a crucial and redemptive distinction emerges between the traditional ideological project of the archive and a self-conscious ideological reconstruction of the archive. It is the Ground Zero and the author’s subsequent reflection on what the experience meant to him that is posited as the originary cause of a reconstituted archive and memory. “Was Nols se groot problem ook my groot redding? My verlossing van wat met my gebeur het, wat in my losgemaak is, daardie dag by Dagbreek-koshuis?” (I 221). Read and interpreted in these philosophical terms, I can think of only one other philosophical text that I have ever found sexually arousing – Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan.

Yes, indeed. It is time for my confession. How long has it been, my son?

Twenty years to be precise. As part of the research I was doing for my PhD I read Leviathan, that brutal 17th century version of the social contract, a philosophical fiction first obliquely introduced into philosophy by Plato in Book II of The Republic. The question that intrigued Hobbes was, given the extent to which we are driven by self-interest, how is such a thing as the state (what he called the “commonwealth”) possible at all? He proposed to answer the question by imagining a world in which the state did not exist: given a collection of men without government, how might we imagine that they would rationally have decided to construct such a thing? Hobbes’s name for that condition that preceded the invention of the state is the “state of nature” and in this state of nature there are no laws or moral codes. It is a domain of werewolves in which the old homo homini homo (man is a man to man) is replaced by homo homini lupus (man is a wolf to man) and each individual is at liberty to take what and whom they want. It is as if Hobbes presented us with a 17th century prequel to Westworld, that fantastic state-of-nature-as-theme-park where there is no limit to the satisfaction of our violent and sexual desires. But here’s the thing (and the reason for my belated confession): for Hobbes the state of nature was not an historical phenomenon that preceded the invention of the state. On the contrary, the state of nature continues to lurk just beneath the surface of the civilized “contract” we entered into in order to survive. The state of nature and the freedoms associated with it resurface every time the social order breaks down: when we travel at night and have to arm ourselves to keep the werewolves at bay; when a hurricane destroys a city and looting becomes the order of the day, and when an unsuspecting archivist walks into the sancta sanctorum of Afrikanerdom only to be taken by another man – because he can and because it makes no difference.

If Van Wyk’s Reddingsdaadbond tour of 1948 marks the “singularity” (the archē coincidence) of the phylogenetic and ontogenetic desire for “maturity”, then the anal sex in the archive – between the two archivists of that memory – is the apotheosis of that maturity in what comes after maturity, namely decomposition, rot and decay – which the melancholy soul somehow never trusts will be followed by the “new dawn” (Dagbreek) of recomposition in re-differentiation. This is Nagmusiek (both composition and text) as “treurlied”, elegy, requiem for the dead – which allows me now to return to the cumulative meanings of Nagmusiek, that hailstorm of distant but related keys, and to summarise them in one last codified table:

Key:

Two closely related keys: G major and D major (or G major and C major, or G major and E minor).

Two distantly related keys: G major and C# major.

Two very distantly related keys: B major and Bb major.

It is early evening when I finish writing this section. I’ve been dreading its writing because I sensed the unavoidable: that even to write about de-differentiation – myne, en dié van “my” mense – takes the imagination down the path of de-differentiation. But I had to do it. Today. Before the weekend starts. I needed to exorcise the Demon of Likeness and the Same. I look at the last table that is still displayed on my computer screen. Nothing quite as satisfying as fighting back with a taxonomy. Then I spend ten minutes cleaning my office, re-arranging everything on my desk. I go to Youtube and find what I am looking for: Msaki’s hauntingly beautiful song Dreams. I’m going to listen to it and then I will decide whether or not I will stay to put the finishing touches to the last section before I go home. With my feet on the desk I listen and, towards the end, briefly close my eyes to savour the last, soothing repetition of the refrain:

Breaking the heart is a silent art.

You pull the pieces apart by putting who you are in a jar

Breaking the heart is a silent art.

You pull the pieces apart by putting who you were in a jar

Breaking the heart is a silent art.

You pull the pieces apart by putting who you’ll be you in a jar

Breaking the heart is a silent art,

It’s a silent art. It’s a silent art

VI

Niente

Die ou paradys

“Protected by patents, garish arrangements, distortions and all infringements”[19]A note Van Wyk made on one of his scores (I 808).

One of the key stylistic developments in harmony that arose in the late Romantic era was the obscuring of the tonic. Composers deliberately tried to avoid, loosen, circumvent, expand or check its gravitational pull. This understanding of the tonic not as functional centre of a harmonic progression, but as referential point of a musical culture (confirmed even – especially by – its avoidance), informed the practices and experiments called atonality and serialism. The result was that the functionality of the tonic in 20th century music as a syntactical force, was embraced as a tension rather than a necessity and other tones (whether diatonic or chromatic) gained independence and prominence.

I am left contemplating one last instance of Van Wyk’s tonality in his own life: the difference between the shy, physically awkward public performer and the jovial, even silly home entertainer as described by Du Plessis (41):

“Die hoogtepunt van daardie heerlike aande van die laat-veertigerjare was [Van Wyk] se optrede as improviseerder – hy kon bv. enige bekende meester se styl naboots – en as mimikus – ek onthou veral Oda Slobodskaja se verhoogverskyning …”

Public anxiety and private silliness: distant but related keys to understanding Van Wyk, not as person or subject of enquiry, but as an Idea. Is it not possible, as Strauss argues, that the way in which Van Wyk has been canonized as metonym of collective melancholy is just a construct, function of a symbiosis that required a Romantic Hero to represent a collective longing for maturity-yet-to-come? It is entirely possible. After all it is abundantly clear that at parties Arnold van Wyk was a real tonic.

I looked at that last sentence with horror. It’s a dreadful pun; a slip of the finger; a Freudian slit, and I should really insert an emoji or [canned laughter] after “real tonic” to indicate that I know it’s a terrible pun that all real musicians and musicologists are sick of. But I cannot bring myself to delete it. There is something about the entire paragraph that intrigues; a pathos hidden somewhere in the “theoretical hailstorm” that over centuries had eroded the gravitas of the tonic to deliver someone such as Van Wyk unto the world stage. I struggle to find the excuse that will convince me to leave the pun there. And yet, I wait. It takes a while but then I see it: it’s the tension between the levity of a bad pun and the gravitational pull of any reference to the tonic. Levity and gravity: they’re quite the pair – like Ebony and Ivory; and, along with that, one last iteration of “the distantly related, each coloured by the tone of the other”.[20]The common ground of levity and gravity is the -ity as noun suffix: “ity” is the anglicised version of the Latin feminine noun suffix of “-itas”, which pertains to abstract nouns, usually substantivised adjectives. Thus, “levitas”, “gravitas”, “severitas”, “brevitas”, “aeternitas”. Gratitude to my colleague Ulrike Kistner for this clarification.

As I prepare to leave I wonder, How many people are actually going to read this little “programme note” (which I think I should dedicate to Daniel-Ben Pienaar)?[21] This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. Probably the same five people who will buy his recording of Van Wyk’s Nagmusiek and other mature piano works. Van Wyk maak nie saak nie; hy saak nie maak nie. Makie sakie; saki maki. It’s time to go. On the way home, I will get some sushi and a big bottle of Saki [canned laughter]. In the escalator on my way down I reminisce about the day I received Aryan’s invitation to write this note and the reason I accepted without thinking about it too much. The obligations of friendship aside I also have a very well-developed appreciation of the useless. I’m probably the last remaining human being who can claim to have actually read both Remembrance of Things Past and The Anatomy of Melancholy[22] This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. in their entirety. As the lift approaches Ground Zero [canned laughter], a quote from Rouse’s preface to The Essential Anatomy of Melancholy which I have made a point of memorizing, flashes through my mind:

“But what is melancholy? It differs from madness only in degree; and when we read of the thousand and one possible causes, we are apt to think that none may escape it, until we learn of the thousand and one possible cures.”[23]W.H.D. Rouse, ‘Preface’ to Robert Burton’s The Essential Anatomy of Melancholy (2002: ix). Dover Publications, Mineola, New York.

| 1. | ↑ | The opening paragraph should make it clear that that this is in no sense a review of this new release but at best a little programme note of sorts. |

| 2. | ↑ | Michel Foucault, ‘The Prose of Actaeon’, in Pierre Klossowski, The Baphomet, Eridanos Press, Hygiene, Colorado, 1988, ppxxi-xxxviii. |

| 3. | ↑ | Suzanne Strauss, “ ‘Ek kan eintlik net hartseer musiek skryf …’. Die selektiewe kanonisering van Arnold van Wyk (1916-1983) se werke’ in LitNet Akademies, Jaargang 10, Nommer 2, Augustus 2013. |

| 4. | ↑ | Stephanus Muller’s Nagmusiek consist of three volumes. In all cases I simply refer to the volume and page number. |

| 5. | ↑ | Ontogeny charts the developmental stages of an individual; phylogeny, that of a collective society, culture, or civilization. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” was the answer to the question that haunted nineteenth-century biologists most, namely: what is the relationship between individual development (ontogeny) and the evolution of species and lineages (phylogeny)? For an extensive and critical study of the history of this idea, see Stephen Jay Gould’s unsurpassed Ontogeny and Phylogeny, Harvard University Press, 1985. |

| 6. | ↑ | Frits Stegmann, “Uit sy pen vloei musiek” in Acta Academica, Reeks B. No. 19, p25. |

| 7. | ↑ | Jacques P. Malan, “Arnold van Wyk in kultuurhistoriese perspektief”, in Acta Academica, Reeks B, No. 19, p12. |

| 8. | ↑ | Ontleen uit Muller I, 673: argief item 013, 4 Folios, bladsy 1-3: Improvisation on a Given Theme, Andante, C mineur, vir klavier, 44 mate, onvoltooid, blou ink. |

| 9. | ↑ | Closely related keys, in a traditional sense, are keys whose key signatures contain one sharp/flat more, or less than the other key (e.g. F major and Bb major: Bb major has one flat more than F major and these keys are therefore considered closely related). Therefore, the more additional sharps/flats we add to a key signature, in comparison to one with only a few sharps/flats, the more distantly related the keys will be (for example, C major and F# major will be considered distantly related). My gratitude to Altus Hendrick from the music department of the University of Pretoria School of Arts for this succinct explanation. Examples of two closely related keys are G major and D major (or G major and C major, or G major and E minor); two distantly related keys: G major and C# major; two very distantly related keys: B major and Bb major. |

| 10. | ↑ | This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. |

| 11. | ↑ | From Muller I 20. Title borrowed from archive number 21 ‘Manuskripboek’, 30. |

| 12. | ↑ | Violence and the Sacred (1995:146) René Girard. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. |

| 13. | ↑ | Hubert du Plessis, “Arnold – aanhef, aandenkings en anekdotes”, in Acta Academica, Reeks B, No. 19, p39. |

| 14. | ↑ | From Leonhard Praeg, ‘Notes on/of Arnold van Wyk’s Nagmusiek: A Melancholy Anatomy. |

| 15. | ↑ | This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. |

| 16. | ↑ | Margaret. |

| 22. | ↑ | This hyperlink is inserted by the Editor and not the Author. |

| 19. | ↑ | A note Van Wyk made on one of his scores (I 808). |

| 20. | ↑ | The common ground of levity and gravity is the -ity as noun suffix: “ity” is the anglicised version of the Latin feminine noun suffix of “-itas”, which pertains to abstract nouns, usually substantivised adjectives. Thus, “levitas”, “gravitas”, “severitas”, “brevitas”, “aeternitas”. Gratitude to my colleague Ulrike Kistner for this clarification. |

| 23. | ↑ | W.H.D. Rouse, ‘Preface’ to Robert Burton’s The Essential Anatomy of Melancholy (2002: ix). Dover Publications, Mineola, New York. |