ATHI MONGEZELELI JOJA

Uninterrogated Phallophilia

It was in the early 1990s, as fine art students at Stellenbosch University, that old time collaborators Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes’ incendiary art began its trademark pissing on the seemingly weakening grip of Afrikanerdom in the “greater” South Africa’s public life in the form of their licentious comicstrips. And like a record stuck in a loop, the Bitterkomix duo is still at it almost 30 years later. The publication of their “erotic drawings” gives us a disorganized trek down memory lane to their pictorial provocations dating as far back as 1995.

There’s a sustained structure that cuts across both books which enables them to share very specific features without necessarily degenerating into a hackneyed homogeny. That is, they do not only share a similar title The Erotic Drawings of…, but both books are introduced by a single essay, followed by a catalogue of images representative of each artist’s work.

In Kannemeyer’s book, the award-winning novelist and scholar Antjie Krog contributes the essay, whilst Kannemeyer himself contributes the text for Botes’ book. Although they are not reducible to each other, much of the books’ deliberate, if not performative, sameness indexes a host of many things shared between the artists over their extended collaborations and relationship. This makes reviewing them simultaneously both easy and intriguing.

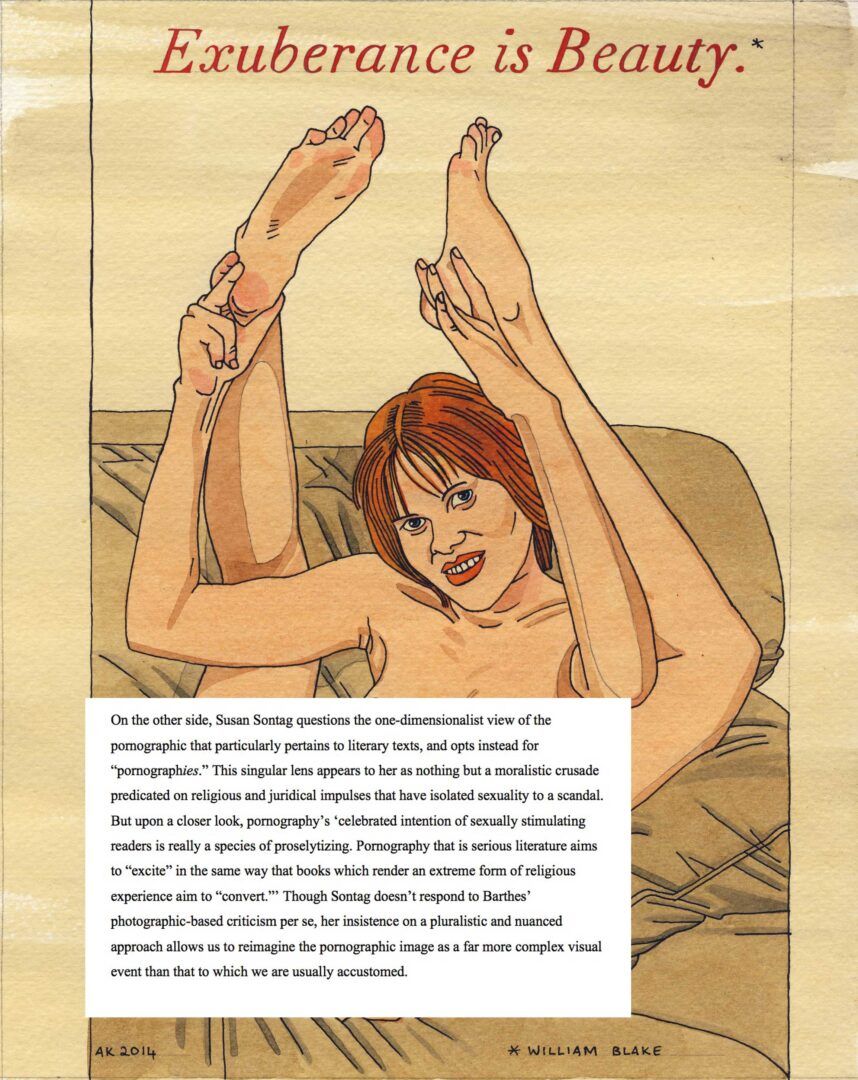

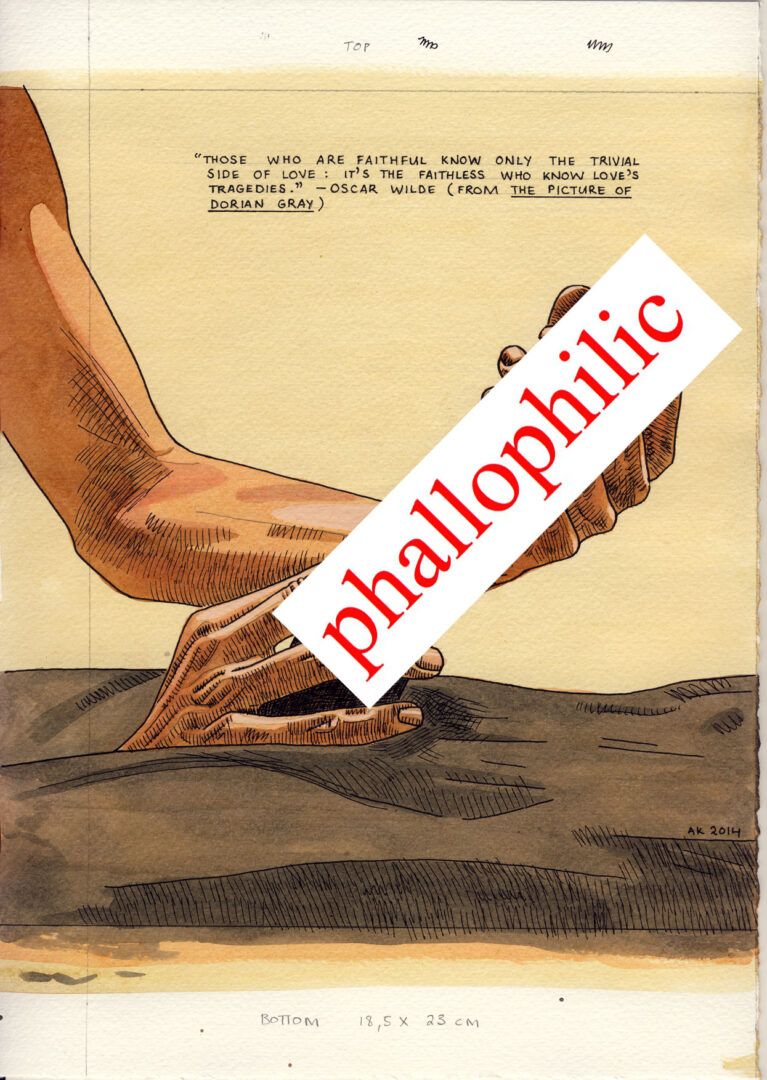

Kannemeyer’s copy, with an auburn color scheme for both front and back covers, is unhinged in its vulgarity and bristles with earthiness. On the front cover, cropped pale feminine hands caress an erect black phallus. Though the piece itself is not featured in the text, the book’s index shows that it is originally from the ink and acrylic drawing, The Faithless (2014). The back piece, Exuberance (2014) depicts a naked white female seated on the couch with her legs wide open with words “exuberance is beauty” punctuating from above the picture, and in the lower right it reads “William Blake”.

Botes’ cover is far more subtle by comparison. However, what makes for an interesting detail is that Botes’ editor here is Kannemeyer, whereas Kannemeyer’s is gallerist Sophie Perryer. Here, it seems the expression “don’t judge a book by its cover” is a wasted piece of wisdom. From our first encounter we know what to expect. Those with frailer hearts and in the company of minors, would probably need to heed this unpretentious countenance and choose a different aisle. In fact, as Kannemeyer writes of Botes’ book as “a no-holes-barred action-packed volume of dynamite. It is an iconoclastic attack on decency and the moral values of the conservative.”

The tension between pornography and erotica is what the books primarily seek to unsettle, as we can garner from their titles. These drawings, writes Kannemeyer “are not intended to be erotic.” If anything, the titles are “an ironic reference to various books with similar titles on mainstream artists such as Picasso, Matisse or Degas.” Krog insists, this ironic twist functions as “a deliberate misnomer for what takes place on these pages: nothing here is erotic, or pornographic for that matter.”

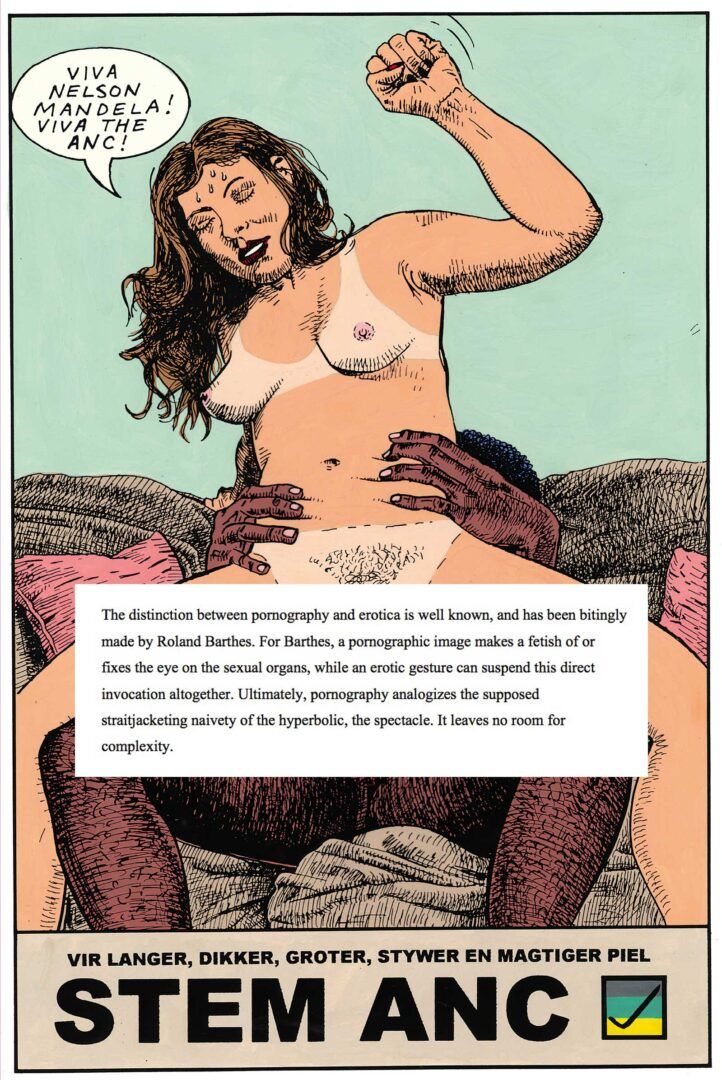

The distinction between pornography and erotica is well known, and has been bitingly made by Roland Barthes. For Barthes, a pornographic image makes a fetish of or fixes the eye on the sexual organs, while an erotic gesture can suspend this direct invocation altogether. Ultimately, pornography analogizes the supposed straitjacketing naivety of the hyperbolic, the spectacle. It leaves no room for complexity.

On the other side, Susan Sontag questions the one-dimensionalist view of the pornographic that particularly pertains to literary texts, and opts instead for “pornographies.” This singular lens appears to her as nothing but a moralistic crusade predicated on religious and juridical impulses that have isolated sexuality to a scandal. But upon a closer look, pornography’s ‘celebrated intention of sexually stimulating readers is really a species of proselytizing. Pornography that is serious literature aims to “excite” in the same way that books which render an extreme form of religious experience aim to “convert.”’ Though Sontag doesn’t respond to Barthes’ photographic-based criticism per se, her insistence on a pluralistic and nuanced approach allows us to reimagine the pornographic image as a far more complex visual event than that to which we are usually accustomed.

According to Kannemeyer, pornographic photography and drawing differ. He doesn’t satisfactorily explain this difference, but points us to the interpretative and manipulative power of drawings, which photographs supposedly lack. This is Kannemeyer’s attempt to rescue the putatively incendiary features of their explicit art, by attributing to drawing a certain singularity. This is obviously nonsense, considering vexing histories of photographic representation in the colonial archive, avant-garde traditions, and postmodern art. In fact, particularisation of the capacity of art mediums today is certainly not abreast with the various developments or even inter-medial practices in contemporary arts. This inter-medial exploration is what Bitterkomix rely on, and they agree “text is particularly effective.” Without text, Kannemeyer and Botes’ art hardly escapes the nomenclatures of pornographic banality. One can make this judgmental point without taking away the draughtsmanship of both Kannemeyer and Botes, at the level of technical and idiosyncratic handling of the material.

This interpretative reliance on “text,” as providing rescue or complexity to what can easily slide into nothing but “the impulse to create explicit drawings,” also turns itself into a spectacle. The tension it bears could easily be a reaction towards the viewer’s banalization of what is purportedly iconoclastic. According to Krog, “The moment text forms part of a visual presentation one’s absorption is disturbed: does one simply look, or does one begin to read and get sucked [emphasis mine] into the thinking brain?” True, one can discover the ironic and destabilizing role texts play in pornographic art, but such disturbance tends to play second fiddle to the oculographic spectacle it displays. Such that the critic tends to an over-compensating reliance on text as a redemptive feature, providing neither clarity nor criticality, but highlighting text as a pictographic eraser.

Reading Botes’ picture, Kannemeyer makes a really disturbing couple of points. In A Bigger Feminist (p83) displays a rape scene of a woman contorted and bound whilst a man towers over her, penetrates her anally and says “Let me start by saying that No One is a bigger feminist than I am.” It is not clear what this textual incorporation wants to do beyond sounding like an imbecilic and unthinkably misogynistic randomness.

According to Kannemeyer, ‘the situation is a construct, and the text is particularly effective because the male defends his action by saying the opposite of the expected. The irony invites thought. My first thought when I read this image was: “Can a man really be a feminist?”’ The pedestrian and bigoted emphasis that claiming to be feminist, immediately undercuts one’s proclivity to violence, makes legible the uncritical and exhibitionistic naivety that undergirds the pornographic impulse a la Barthes. Put differently, that the irony resides in man’s inability to become feminist or not, which by the way has no bearing whatsoever on the violation at hand, speaks of an exalted ignorance that emerges out of the unchecked power of white supremacy.

This is spectacle of the

disposition, a dogged navel-gazing undertaking that fixes its imagination on the crotch and nowhere else.

Consider the image Stem ANC (p35) in Kannemeyer’s book. The image shows an interracial couple having sex on the couch, in the famous “hot seat” position. The white woman has a fist in the air as she’s been penetrated by a black faceless man from behind, whilst saying “Viva Nelson Mandela, Viva ANC”. At the bottom of the page, it says, in Afrikaans “vir langer, dikker, groter, stywer en magtiger piel VOTE ANC.”

The capturing of sexuality in South African visual arts, is something not unique to the bitterkomix’s “no-holes-barred” approach. In Prince Dube’s 2005 catalogue to the Dumile Feni Retrospective, there is an entire section dedicated to the artist’s eroticism and according to Mandla Mlotshwa, Dumile’s “erotic works display joy, pleasure and excitement, as well as peace, gentleness, a sharing of spirits, feelings and moods and the simultaneous giving and receiving of pleasure.” In such works, sex is directly engaged or portrayed, perhaps to the total dismay of our arts and culture ministry who are reputed to have staged walk-outs at the mere display in public of a nipple.

However, for Kannemeyer and Botes, sex is a weapon for stigmatization. I mean, for how long will one repeat the image of a lustful and sexually active Afrikaner? The conservative Afrikaner, who is the imaginary target of much of this visual attack, has however recently enjoyed a nostalgic sense of reprieve ever since the likes of Kannemeyer and Botes have turned their tools on the black politician. He or she enjoys these venereally inflected pieces of caricature with the same zeal and intrigue as everyone else.

Recently this recourse to a pornotropic visuality, notably retrieved from the image-bank of colonial and apartheid era racial grammars, has become the moral underbelly of “state capture” imagery, in which racial stereotypes were unleashed without consequence, uniting the conservatives, liberals and leftists in the name of repairing a resilient settler colonial imaginary called South Africa. Images of blacks as buffoons and hyper-sexualised anti-persons, objectively recalibrate the psychic and libidinal economies of white supremacy. The power of racist caricature and its spectacle – embarrassing as it might be for some “white progressives” – underwrites the very conception of a South African polity so eagerly protected, as the constitutive condition of anti-black violence. But someone can counterpose this line of inquiry, and say “but he’s subjecting everyone to ridicule, Black and White.” Funny thing is that this comparison works from a completely naive basis. White people having sex might invoke shock and embarrassment, however it doesn’t invoke any preconceived defects that denormalize their humanity and sexuality. However, the same act for blacks not only takes on a new guise, the artists themselves, as their previous works show, need to reconstruct the bodily being of Blackness that makes seeing copulating blacks as excessive, bestial and extra-humanly.

So the re-entry of the racial pornotrope into the visual lingua franca of our public discourse – if, indeed, it had ever left – as “good sense” in the Gramscian sense, can only be exasperating. It leaves one totally vexed and confused, in how it constantly eludes us, or better, how it delimits critical reception as a renewed form of political and cultural censorship. Such criticism is quickly read as reversing the gains of the constitution; misreading the ironic intentions of the artists; or at best, gagging critical whites from voicing their political discontent. It is both criticism’s ally and nightmare, in that it feigns itself as dissent but can never confront the affective and political injury it incessantly recycles on the black body. As such, the aesthetic of pornographic art in South Africa enjoys a partial and contingent role, but very little of its inner troubles are interrogated. If anything, the work of Anton Kannemeyer and Conrad Botes represented in these books, exemplifies, quite crudely, the aesthetic unconscious of white South African cultural expression. They articulate with visual audacity a generic feeling of certainty and invincibility only ever known and experienced by those enjoying the poisoned gifts of racial domination.