MICHAEL BHATCH

Africa Synthesized: A Sonic Essay

This compilation of synth-based music was quilted together from my personal record collection, and constitutes of tracks that are not generally available, or widely referenced within mainstream discourse and dialogue around African electronic music. Each track should be understood as such, and, perhaps, as mere fragments of the obscure histories of electronic music experimentation and techno-artistic expression in Africa. This ‘sonic essay’ is not concerned with engaging electronic music in Africa through its chronological trajectory, but rather through how it interacts with human bodies on the dance floor, and how these human interactions with electro-sonic experiments, in turn, influence street culture and counter-culture.

Situating this sonic essay on the dance floors of Africa is important as it is indeed the physical context, in which the music is consumed and experienced, that influences its sound design. In other words, the dance-floor is where many aspects of electronic music production manifest and come alive, it is where the magic of electronic music is felt. To tease out these loose ‘themes’, I explore electronic dance music that was produced between 1974 and 1994, as this era of production showcases an innovative time in electronics when (mostly) Japanese electronic instrument producers were creating fascinating new synthesizers, drum machines and sound effects units. During this time these new innovations became widely available to African musicians who used and, often times, ‘misused’ them to shape modern electronic music. This period also coincides with the collapse of the colonial enterprise, which created a fertile context in which experimentation, imagination and innovation could thrive like never before.

That being said, this sonic essay hopes to usher you towards an appreciation for the innovative techniques that were employed in the sound design, sound synthesis, production, recording and post production of each track that is presented within its body. It hopes that each fragment of sound demystifies electronic music production in Africa a little bit more for the listener.

As a guide that serves to facilitate the ‘defragmenting’ process during the listening experience, peruse the notated tracklist below:

The Genuines – Doctor Love is ghoema punk/electro rap from Cape Town. It was released in 1989 on Crossover Records, and could be regarded as one of the earliest examples of South African Rap. A fine example of early expressions of afro punk too.

Ray Lema – Peuplo Eyo was released in 1985 and features the afrobeat progenitor Tony Allen on drums. The track almost serves as a blueprint for later African electronic music experiments such as Rocket Juice and the Moon and is reminiscent of Detroit techno, which was coming into existence in the USA around the same time. This techno-Africa connection recently manifested again as Tony Allen and Jeff Mills, one of the founding figures of techno, teamed up for a collaborative techno-afrobeat album which highlighted the connection between traditional drums and drum machines.

The Chris Hinze Combination – African Rapness is a bold fusion of electro rap and jazz-funk with African rhythms. It does a great job of collapsing the electronic into the organic. Released in 1984, with synthscapes that still feel futuristic in 2020, this track was forward-thinking and sonically innovative. It reminds me of kasi-futurist work of contemporary South African rapper Okmalumkoolkat.

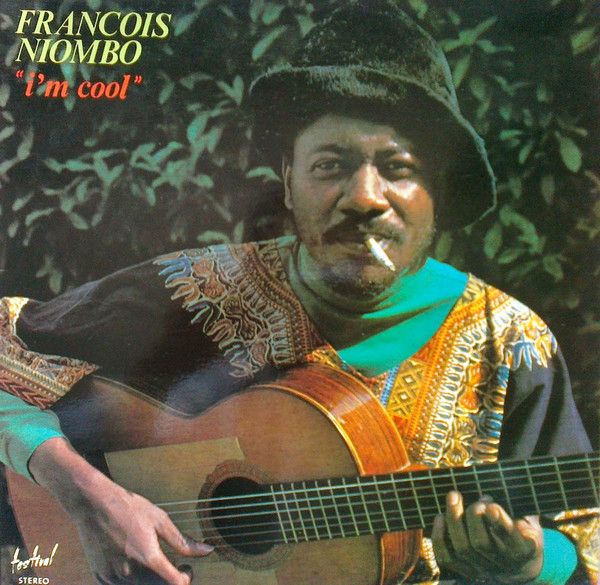

Francois Nyombo – Funky Child (1976) is a Congolese psychedelic disco jam that brings together the guitar electronics of Hendrix with the space aesthetic of the disco movement. I suspect electronic effects may have been added during the production phase to create the overall ‘dub-iness’ of the track.

Gérard Cimiotti et Son Ensemble – 40 Mozart (1974) is an Mauritian electronic music rendition of a Mozart classic. It sounds like the arcade game soundtracks that emerged in the early ’80s.

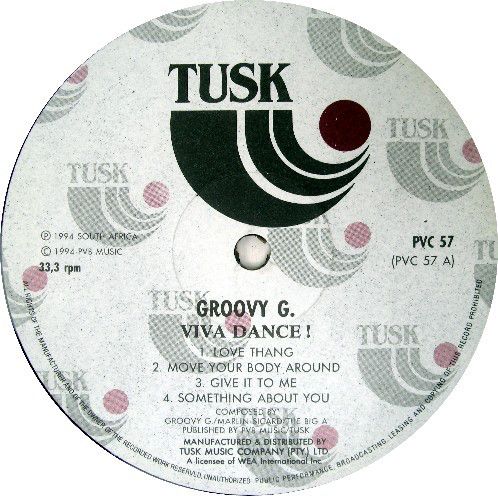

Groovy G – Love Thang (1994) is an example of the emerging electronic music sound of the ‘new South Africa’. The track is hyper-urban with multiple influences from other black electronic music scenes in the diaspora, Chicago specifically. This one gets filed under kwaito/mid tempo house music in South Africa.

Image – You want to do it (1987) features the great kwaito innovator Don Laka on keys. I love the vocal effects, synthesizers and overall electronic sound design of this funky banger. The song is also quite jazzy and anticipates kwaito. Side note: Don Laka was one of first South African musicians to use a drum machine in his music.

Zone 3 – You are mine (hot dance mix) (1986) is an example of experimental afro-synth pop. The song would later be sampled by kwaito artists. The synths are awesome here and the spaced-out vocal ad-libs take the track to another level sonically.

Midnite Magic 1 – Zambezi (1988) is atypical electronic music from Zimbabwe. It is resonant of the work of deep house progenitor and electronic music legend Larry Heard. It is an absolutely amazing example of the innovative and interesting electronic music that was coming from the continent in the ’80s. Listen to the lyrics.

Wizzy Masuke – Antsatiwamina (1991) is a glimpse of the magic that happens when electronics are incorporated into and used to produce traditional African dance-oriented music. This particular track allows us to imagine other forms of electronic dance music that are not overwhelmingly influenced by house, hip hop or techno. This is what Mozambican dance floors sounded like in the ’90s.

Night Force and the Tom Cats – Search for Love was produced by Enoch Ndlela in 1981. South African funky, futuristic, spacey disco at its best, with the depth and feel of deep house. Who would have thought that this kind innovative electronic music experimentation was happening during the apartheid era? In 2019 I worked with Afrosynth records, in conjunction with Rush Hour Music, to reissue this almost forgotten track for the global vinyl reissue market.

Mandingo – Powerhouse (1990) is a sample of African electronic music that was produced outside the continent. Co-producer Foday Musa Suso hails from Gambia but made a life for himself in Chicago, the birthplace of house music. Perhaps this explains why house music/techno is at the core of this track.

Rex Rabanye – African Wedding (1986) is the reason why many DJs regard Rabanye as a pioneer of African electronic music. What you hear is African choral gospel reimagined and electrified through the use of drum machines and synthesizers. It is ethereal and uplifting and is known to be played at weddings and social gatherings that involve dancing. Modern afro house music draws heavily on this sound.

Peta Teanet – Africa (cement mix) (1990) is a beautiful electronic dance music banger by the king of Shangaan disco. It is an interesting example of how new music technologies facilitated the expression of rural (Shangaan) rhythms within the urban electronic music mold of Black America.

Mory Kanté – Yéké Yéké (Afro acid mix) (1987) is an electronic music remix of the Guinean/Malian vocalist and kora player’s work, and was created for nightclub scenes of New York, Chicago, London, Paris etc. The song was a global hit that would later spark interest in many electronic musicians from across the globe to draw on African music and rhythms for influence. This remix left its mark on contemporary French house music production.

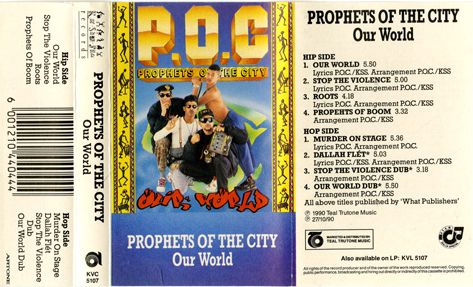

Prophets of the City – Stop the Violence (1990) contains a sample of earlier ghoema/Cape jazz recordings. At the time of its release sampling wasn’t a common or widespread practice in African music production. While the song might not sound incredibly ‘electronic’, I appreciate the use of technology (in the form of sampling) to establish the geographical and socio- cultural context in which the lyrics operate. This is consistent with the chrono-political and hyper-technological nature of hip hop.