ANTJIE KROG

‘The Convert Writes Back’

‘Imbuka liyaziphendulela’

(excerpt from A Change of Tongue, 2003)

(icashunwe kuncwadi Ukushintsha koLwimi, 2003)

Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch codes without having always to be translated… my mother tongue will be illegitimate. – Gloria Anzaldúa

Ngize ngikhululeke ukubhala ngalimimbili ngiphinde ngishintshe ukwenza ngaphandle kokuhumushwa…ulwimi lwami lukamame luyohlala lungekho emthethweni – Gloria Anzaldua

It is normally supposed that something always gets lost in translation; I cling obstinately to the notion that something can also be gained. – Salman Rushdie

Kujwayelekile ukusola ukuthi okuningi kuyalahleka uma sihumusha; Ngibambelela ngenkani kumbono othi kukhona esingakuzuza. – Salman Rushdie

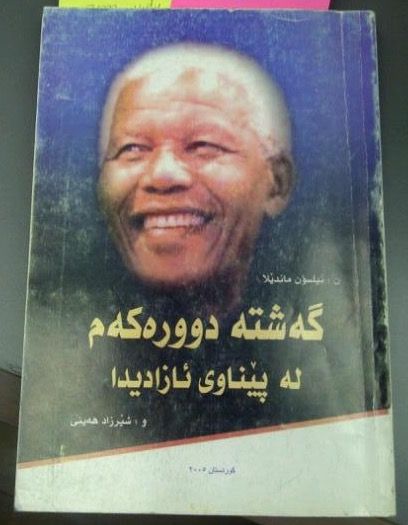

Vivlia Publishers have asked me to translate Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk To Freedom into Afrikaans. I find myself in Mandela’s sitting room in Houghton, Johannesburg, along with the designated translators of three other editions, waiting to discuss the work that lies ahead. Prof. Bheki Ntuli will be doing the isiZulu version, Prof. Maje Serudu the Sepedi, and Prof. Peter Mtuze the isiXhosa.

I-Vivlia Publishers ingicele ukuba ngihumushe incwadi kaNelson Mandela i-Long Walk to Freedom (Indlela ende eya eNkululekweni) ngesiBhunu. Ngizithola ngisendlini kaMandela ese-Houghton, eGoli, kanye nabanye abahumushi balencwadi ngezinye izilimi, silindele ukudingida umsebenzi osasihlalele. USolwazi Bheki Ntuli uzokwenza eyesiZulu, uSolwazi Maje Serudu uzokwenza eyesiPedi, kanti uSolwazi Peter Mtuze uzokwenza eyesiXhosa.

It is a relaxed Mandela who walks into the room. He embraces us warmly and teases Prof. Ntuli about the fact that he does not yet have a grey hair on his head. ‘Muti,’ says the professor, ‘great muti we have in KwaZulu to keep an old man young!’

Prof. Mtuze indicates that he will be translating the work into classical isiXhosa. This is the story of a Xhosa prince, so to speak, and Xhosa royalty should not speak street Xhosa peppered with a lot of English words. His problem is the exact relationship between Mandela and Kaiser Matanzima. The English book simply uses ‘nephew’, but in isiXhosa there are particular words for every kind of relation, specifically denoting age and hierarchy. Mandela and Matazima had several clashes over the years and, depending on the specific way in which they are related, a Xhosa reader would be able to draw conclusions about whether Mandela treated Matanzima with unbecoming disrespect. It takes them almost a quarter of an hour to work it out.

Kungena UMandela okhululekile endlini. Uyasanga ngemfudumalo bese edlalisa (eteketisa) uSolwazi Ntuli ngokuthi namanje akakabi nazo izinwele ezimpunga ekhanda lakhe. ‘UMuthi,’ kusho uSolwazi, ‘Sinomuthi onzima KwaZulu ukugcina indoda endala ingcane!’ USolwazi Mtuze wabonisa ukuthi uzohumusha lomsebenzi esebenzisa isiXhosa sasemdandulo. Lena yindaba yenkosana yakwaXhosa, singasho kanjalo, amakhosi akwaXhosa awakhulumi ulwimi olejwayelekile nolufakelwe amagama esiNgisi. Inkinga yakhe ubudlelwane phakathi kukaMandela noMatanzima. Incwadi yesingisi isebenzisa igama mshana (‘nephew’), kanti ngokwesiXhosa kunamagama aqondene nazo zonke izihlobo, ikakhulukazi ezibonisa ubudala kanye nezinga emphakathini. UMandela noMatanzima bake banokuqagulisana eminyakeni eyedlule kanti, ngokwendlela abahlobene ngayo, umfundi wesiXhosa angakwazi ukubona/ukwehlulela ukuthi uMandela wamuphatha ngenhlonipho engajwayelekile na uMatanzima. Kwabathatha ikota yehora ukuxazulula lenkinga.

Professor Ntuli says that he wants every Zulu to be able to read the book with ease and enjoyment, to absorb it as part of her own life, to make it a text she can live by. His translation will veer more towards everyday isiZulu, which means that he may use words like ‘i-democracy’ and ‘i-gallery’. But of course he will employ a different register when it comes to the political speeches and praise songs. He would really like to translate Mandela’s Rivonia Trial speech in a kind of lofty, praise-song style.

USolwazi Ntuli uthi ufuna wonke umuntu ongumZulu akwazi ukufunda lencwadi kalula futhi akuthakasele, ayemukele njengenxenye yempilo yakhe, ayenze imibhalo angaphila ngayo. Ukuhumusha kwakhe angeke kuyele olwimini lwansuku zonke lwesiZulu, okushukuthi angasebenzisa amagama afana nelithi ‘i-democracy’ kanye nelithi ‘i-gallery’. Kodwa ke uyosebenzisa indlela eyehlukile uma kuziwa ezinkulumweni zezombusazwe kanye nezibongo zakhe (izihayo). Angathanda ngempela ukuhumusha inkulumo kaMandela ye-Rivonia Trial (Icala lase Rivonia) ngolwimi olucwengekile, oluthi alube ubumbongi.

Mtuze will not be using words like ‘i-democracy’. Alternatives do exist in Xhosa, he says, and now is the perfect time to dust them off and have them take their rightful place in the language.

UMtuze angeke asebenzise amagama afana nelithi ‘i-democracy’(intando yeningi). Akhona amagama asho lokhu ngesiXhosa, usho njalo, futhi manje isikhathi esilungele ukuthi athintithwe abekwe endaweni yawo efanele olwimini.

Prof. Serudu and I ask why Mandela wants the book translated into all South Africa’s languages. Research has surely shown him that people with an interest in the book have probably already read it in English, and that, with the exception of Afrikaans, books sell particularly badly in the other tongues. We cannot think of a single bookshop that keeps books in any of the African languages.

USolwazi Serudu nami sambuza umandela ukuthi kungani efuna lencwadi ihumushwe ngazo zonke izilimi zaseNingizimu Afrika. Ucwaningo selumbonisile ngokungananazi ukuthi abantu ebebeyifuna lencwadi sebeyifundile ngesiNgisi, kanye nokuthi, ngaphandle kolwimi lwesiBhunu, izincwadi ziyehluleka ukudayisa ngezinye izilwimi. Asinakucabanga ngisho esisodwa isitolo sezincwadi esigcina izincwadi ngezinye izilimu zaseAfrika.

‘This book has been translated into practically all the languages of the world. I can go to any place on earth and my story can be found there in that language. Except here.

Here I exist only in English.

I want to be part of all the languages of my country.’

‘Lencwadi isihumushwe ngazozonke izilimi zomhlaba. Ngingaya noma ikuphi emhlabeni udaba lwami luyatholakala ngolwimi lwakhona. Ngaphandle kwala.

Lapha ngikhona kuphela ngesiNgisi.

Ngifuna ukuba ingxenye yazo zonke izilwimi zezwe lami.’

‘You wrote a poem about me in which you named all the ancestors on my mother’s side,’ Mandela says to me as we are walking out. ‘How did you know that?’

‘Ubhale inkondlo ngami lapho ubale zonke izinyanya ohlangothini lukamama wami,’ kusho uMandela ngesikhathi sesiphumela phandle. ‘Ukwaze kanjani lokho?’

‘I translated the praise poems delivered at your inauguration as president. The first poet used your mother’s ancestry and this was pointed out to me as most unusual.’

‘Ngahumusha izibongo ezahaywa ekubekweni kwakho njengoMongameli. Imbongi yokuqala yasebenzisa izibongo zezinyanya zikamawakho kanti lokhu ngakutshelwa ukuhi akujwayelekile.’

‘One’s language should never be a dead end,’ he says, as he takes his place among us for the usual photograph. ‘That is why I believe in translation: for us to be able to live together.’

‘Ulwimi lwakho akumelanga lube umgwaqo ophelayo,’ kusho yena, ngenkathi ema phakathi kwethu ukuze sithathe isithombe njengenjwayelo. ‘Yingakho ngikholelwa ekuhumusheni, ukuze sikwazi ukuphilisana.’

While they are posing, I ask, ‘You have always married strong women, Sir. What is it about them that attracts you?’

Ngenkathi sisamele ukuthatha izithombe, ngabuza, ‘Uhlale uganwa amakhosikazi anamandla, Mhlonipheki. Yini ngabo lena ekudonsela kubo?’

He laughs. ‘It is not I who chose them, it is they who chose me.’

Ahleke. ‘Akumina engibakhethayo, yibo abakhetha mina.’

On the plane home, I think about the whole notion of translation. Perhaps translation is one of the most accurate barometers of the power of a language. It seems to me that works are usually translated from weaker into mightier languages. The more a language is threatened, the stronger the urge becomes to translate from that language. The mightier a language, the stronger the urge to be translated into that language. England or America could not be bothered how many of their major works are translated into other languages, whereas Holland, Sweden, Germany, France not only ensure that books by J.M. Coetzee, John Updike, John le Carré, Chinua Achebe are translated into their languages, but also that the important works in their own tongues are translated into English.

Ebhanoyini ngibheke ekhaya, ngicabange ngayo yonke lento yokuhumusha. Mhlawumbe ukuhumusha yikhona okusibonisa kabanzi ngamandla olwimi. Kubukeka kimina sengathi imisebenzi ijwayele ukuhumushwa isuswa olwimini olubuthakathaka iya olwimini olunamandla. Uma ulwimi lusengcupheni yokushabalala, kuba nesidingo esikhulu sokuhumusha ususela kulolo lwimi. Uma ulwimi lunamandla kakhulu, kuba nesidingo esikhulu sokuhumushela kulolo lwimi. INgilandi neMelika abanandaba nokuthi mingaki imisebenzi (imibhalo) yabo ehumushelwe kwezinye izilimu, kanti eHolendi, eSwideni, eJalimane, eFransi abaqiniseki kuphela ukuthi izincwadi zika J.M. Coetzee, John Updike, John le Carre, Chinua Achebe zihunyushwa ngezilimi zabo, kodwa futhi nokuthi imisebenzi ebalulekile ezilimini zabo ihunyushelwa esiNgisini.

I read an interview with the Dutch poet Gerrit Komrij about translation. ‘Translation creates space in a language. It lets the osmosis of human knowledge take place between cultures. Translation is like gymnastics for one’s language, an exercise in language that not only makes literature accessible, but ensures that all kinds of concepts are brought in for which you have to discover equivalents. To me, translation seems essential for the depth and suppleness of a language.

Ngifunde inkulumo ngxoxo nembongi yase-Dashi (Dutch) uGerrit Komrij mayelana nokuhumusha. ‘Ukuhumusha kuyaluvula ulwimi. Kwenza ukuxubana kolwazi kwenzeke phakathi kwamasiko. Ukuhumusha kufana ne-gymnastics(umdlalo wokuzivocavoca) olwimini lwethu, umsebenzi ongenzi nje kuphela ukuba imibhalo ifundeke, kwenza nokuthi yonke imiqondo ibekwe obala ukuze iqhathaniseke. Kimina, ukuhumusha kubalulekile ekujuleni kanye nasebubanzini bolwimi.

‘Clinging exclusively to your own language creates anxiety and narrow-mindedness. The translation of works from other cultures makes for a more open-minded society.’

‘Ukubambelela olwimini lakho kuphela kudala ixhala kanye nomqondo omncane.

Ukuhumushwa kwemisebenzi evela kwamanye amasiko kwenza umphakathi uvulekelwe ingqondo.’

In South African literature, English is the language in which writers reach each other, meet each other, get into conversation or debate. And, in the way of a mighty language, English does not care whether there are brilliant writers in Afrikaans or isiXhosa or Sepedi; if the writer does not write in English, he or she does not really exist.

Emibhalweni yasNingizimu neAfrika, isiNgisi ulwimi ababhali abatholana (abaxhumana) ngalo, bahlangane ngalo, bakhulumisane noma baqophisane. Kanti, ngokwendlela yolwimi olunamandla, isiNgisi asinendaba ukuthi kunababhali abahle olwimini lwesiBhunu, isiXhosa neSipedi; uma umbhali engabhali ngesiNgisi, akekho ndawo.

I realize that translation is therefore one of the key strategies for survival – not only for writers and publishers, but especially for a language itself. It it does not develop a strong translating tradition, it can shut up shop, because some of its best writers will leave. If power shifts turn English into the language where people meet, then writers in the smaller languages should demand the right not only to write in their own language, but to be translated in order to form part of all the voices of their country.

Ngiyaqonda ukuthi ukuhumusha iyona ndlela eyisihluthulelo ezindleleni zokuphila – hhayi kubabhali kuphela nabashicileli, kodwa ikakhulukazi olwimini uqobo. Uma lungaqiniseki ekusunguleni isiko elibanzi lokuhumusha, lingavaleka, ngoba abanye bababhali balo bangafudukela kwezinye. Uma ukushintsha kwamandla kuphendula isiNgisi ulwimi abantu abahlangana ngalo, kuzomele ababhali bezinye izilwimi baphoqe bafune ilungelo hhayi kuphela elokubhala ngezilimi zabo, kodwa ukuhumushwa ukuze babe ingxenye yawowonke amazwi ezwe labo.

‘Translation is empowering, because in my mother tongue I have access to the entire pipe organ and all its registers; in my acquired language I try to express myself on a toy piano,’ I think aloud.

‘Ukuhumushwa kunikeza amandla, ngenxa yokuthi ngolwimi lwebele ngiba nokuthola okuningi angingakusebenzisa; olwimini engilufundile kufana nokuzama ukudlala ipiano eyi-thoyizi,’ ngiyacabangela nje.

‘Be careful,’ warns Christina, a Swedish expert on translation, as the two of us chat on a balcony in De Waterkant. ‘People who prefer not to write in their mother tongues often enrich a language precisely because they are not cluttered with tradition or intimidated by the great writers of that language. But the right to be translated should exist in all languages.’

‘Qaphela,’ kuxhwayisa u Christina, onguncweti wezokuhumusha wase-Swideni, ngesikhathi sikhuluma sisonqenqemeni (balcony) lwe De Waterkant. ‘Abantu abakhetha ukungabhali ngezilwimi zabo bayalunonisa ulwimi ngoba ababambelele emasikweni noma besabe ababhali abakhulu balolo limi. Kodwa ilungelo lokuhumushwa kumele libe khona kuzo zonke izilimi.’

‘I feel at times embarrassed that I want to be read in English, like I have sold out, betrayed something, or revealed a shameful desire … and I am not clear how much of it has to do with a resistance to colonization, giving in to power, being owned, accepted by the colonizer’s hand – because English has become the door to the Father, if you know what I mean.’

‘Ngizizwa nginamahloni ngezinye izikhathi ukuthi ngifuna ukufundwa ngesiNgisi, engathi ngilimbuka(umthengisi), kunengikulahlile, noma ngiveze lokho ukulangazelela okubanga amahloni…kanti angiqondisisi kahle ukuthi ngabe lokhu kunento yokwenza nokuphikisana nokucindezelwa, ukuzisondeza kwabasemandleni, ukuba ngaphansi kwabo, wamukeleke ezandleni zabacindezeli – ngenxa yokuthi isiNgisi sesiphenduke umnyango oya kuBaba, ngethemba uyayiqonda lena engiyishoyo.’

‘Why are you interested in the Father?’

‘Kungani unendaba noBaba?’

‘That is my problem: I am not. I think I simply want to be read by people whom I care for, and some of them happen not to understand Afrikaans. I know full well that I can never play a role in English literature as I do in Afrikaans, because I do not have T.S. Eliot or Philip Larkin in my bones. I have somebody else. I actually think you can only revolutionize a language if you have grown up in it, in that house; coming from somewhere else, you can only bring interesting versions of living. The changes you have brought to your own living spaces will get lost in an English house.’

‘Ileyo ke inkinga yami: anginandaba. Ngicabanga ukuthi ngidinga ukufundwa abantu enginendaba nabo, kanti abanye babo kutholakala ukuthi bayasiqonda isiBhunu. Ngazi kahle ukuthi asoze ngadlala indima ekubhaleni ngesiNgisi njengoba ngenza ngesiBhunu, ngoba anginaye u T.S. Elliot noma uPhillip Larkin emathanjeni ami. Nginomunye nje umuntu. Ngikholelwa ekutheni ungashintsha ulwimi kuphela uma ukhulele kulona, kuleyondlu; uma uvela kwenye indawo, ungaletha kuphela izinhlobo ezahlukahlukene zokubona impilo. Izinguquko ozilethe kusikompilo lwakho endaweni yakho zingalahleka endlini yesiNgisi.’

Christina smiles as if all of this is amusing. Then she begins to talk about how the act of translation works.

UChristina uyamoyizela sengathi konke lokhu kuyathokozisa. Bese eqala ekhuluma ngendlela esebenza ngayo indlela yokuhumusha.

‘Some things are easy to translate. Other things more difficult. But with a little effort the difference from one language to another can be bridged. At times, however, things will come up that strike you because of their difficulty, their complexity, the way they resist the resources you yourself use, in your own language and culture, to make sense of the world. These things – from lexical items, through speech acts, to fundamental notions of how the world works – are called “rich points”. And a translator has to be very aware of the rich points relevant to a particular translation task, aimed at opening communication between the groups or subgroups on either side of the language barrier.’

‘Ezinye kulula ukuzihumusha. Ezinye zilukhuni. Kodwa ngokuzama nokuzimisela igebe (umehluko) phakathi kolwimi nolunye ungavaleka. Ngezinye izikhathi, kodwa, kunezinto ezizovela ezikushaya ngenxa yobukhuni, ukujula kwazo, nangendlela ezingavumi ngayo indlela osebenza ngayo, ngokolwakho ulwimi kanye nesiko, ekuqondeni umhlaba. Lezizinto – ngokwamagama abhalwayo,(lexical), ngokwenkulumo nokokwenza, kuya esiqwini nezindlela zokusebenza komhlaba – abizwa ngokuthi “amaphuzu acebile”. Kanti umhumushi kumele abe nolwazi mayelana nalawo maphuzu acebile aqondene nokuhumushwa komsebenzi othile, okuqondwe ngakho ukwakha ukuxhumana phakathi kwamaqoqo kanye nezinhlanga ezinxazonke zezilimi.’

‘Are you saying that translation is a cultural exchange?’

‘Kungabe uthi ukuhumusha ukuhwebelana kwamasikompilo?’

‘More than that. It is a comparing of cultures. Translators interpret source-culture phenomena in the light of their own culture-specific knowledge of that culture.’

‘Kungaphezu kwalokho. Ukuqhathanisa amasikompilo. Abahumushi bahumusha umsuka wesiko ngendlela abakhanyiseleke ngayo ngokwelabo isiko kanye nolwazi abanalo ngalelo sikompilo.’

‘Give me an example.’

‘Ngiphe isibonelo.’

‘Take the word “forefather”. Or would you use the word “ancestor”? Does it carry the same content? A foreign culture can only be perceived by means of comparison with one’s own culture, the culture of primary enculturation. There can be no neutral standpoint for comparison. Everything we observe as being different from our own culture is, for us, specific to the other culture. The concepts of our own culture will thus be the touchstones for the perception of otherness.’

‘Ukuthatha igama “BabaMkhulu”. Noma uzozebenzisa igama elithi “amadlozi”? Kungabe liqukethe okufanayo? Isiko langaphandle lingaqondwa ngendlela yokuliqhathanisa nelakho isikompilo, isikompilo oqale wafundiswa ngalo. Akukho ukuba phakathi nendawo uma siqhathanisa. Yonke into esiyibona njengeyehlukile emasikweni ethu, kithina, ivela kuphela kwamanye amasiko. Izindlela zamasiko ethu zizoba isisekelo esiqonda ngayo abanye.’

Christina can see that I do not understand. ‘Translation is essential if we are to learn to live together on this planet. We have to begin to translate one another.’

UChristina uyabona ukuthi angiqondisisi. ‘Ukuhumusha kubalulekile uma sizophilisana kulomhlaba. Kumele siqale ukuhumusha imisebenzi yabanye.’

‘I am not quite sure how these ideas apply to Mandela’s book. He wants to be translated from one of the mightiest languages in the world into a few powerless ones.’

‘Angiqinisekile ukuthi lemiqondo ingena kanjani encwadini kaMandela. Ufuna ukuhumushwa esuka kolunye lwezilimi ezinamandla emhlabeni eya ezilimini ezingenamandla.’

‘The best example to look at is the Bible, which was translated during the nineteenth century, with great dedication and eagerness, into several languages of the South. As you know, not only were these languages powerless, but their speakers were also illiterate, with no written tradition. Although perhaps intended otherwise, these Bible translations are seen today as a form of colonization in the guise of conversion and ‘civilization’. It was how Western values gained access to closed communities, in order to destroy what were regarded as primitive traditions. In writing them down, the missionaries adapted the languages, sometimes with scandalous distortions, in order to convey the Christian message. This process trapped languages in structures that can at best be described as hybrid: on the one hand, the language as people use it is oral and flexible and “pagan”; on the other hand it is written down, and inflexible, and the carrier of the “highest and best of Western values”.’

‘Isibonelo esihle esingasibheka iBhayibheli, elahumushwa ngeminyaka yeshumi nesishiyagalolunye ekhulwini leminyaka, ngokukhulu ukuzimisela nokulangazelela, liyiswa ezilimini ezimbalwa zaseNingizimu. Njengoba wazi, hhayi ukuthi lezizilimi zazingenamandla nje kuphela, kodwa abakhulumi bazo babengafundile, bengenalo isiko lemibhalo. Noma inhloso yayingeyinhle, lokhu kuhumushwa kweBhayibheli kubonwa njengendlela yokucindezela ngendlela yokuphendulwa kanye nokuphucuzeka. Iyona ndlela izimfundiso zaseNtshonalanga ezakwazi ukungena ngayo emiphakathini eyayivalekile, ukuze ibulale lokho eyayikubona njengesikompilo eseledlulelwe isikhathi. Ekubhaleni lezi zilimu, abafundisi benkolo baguqula lezi zilwimi, kwezinye izikhathi ngendlela enehlazo nokuhlanekezela, ukuze kwedluliswe umlayezo wobu-Krestu. Lendlela yabopha izilwimi ezakhiweni esingazibiza kangcono ngokuthi ziyimifakela (hybrid): ngakolunye uhlangothi, ulwimi ngendlela abantu abalusebenzisa ngayo luyashintsheka futhi “lunobuqaba”; kwelinye icala lubhalwe phansi, futhi aluguquki, futhi luqukethe “imigomo ephezulu nengcono yase Ntshonalanga”.’

It was only after I started translating Long Walk To Freedom that I realized to what extent Mandela’s story is a case of ‘the Convert Writes Back’.

Kwaze kwaba sekuqaleni kwami ukuhumusha incwadi kaMandela ethi Long Walk to Freedom (Uhambo olude oluya enkululekweni) lapho ngabona khona ukuthi udaba lwakhe udaba “Lwembuka Liziphendulela.”(the Convert Writes Back).

Translated into isiZulu by Mkhulu Maphikisa

See A Change of Tongue for original references.