ZARA JULIUS

(Whose) Vinyl in (Which) Africa? A Zoom Fiasco

A few years ago, I was sitting in the back seat of a friend’s car, selecting music off my phone for the car ride. My friends and I had invited someone we knew socially to join us on our day out of the city. Scrolling through my limited iTunes library, I put on a compilation that features an array of South African artists; Madosini, Dizu Plaatjies’ Amampondo, Madala Kunene, Pops Mohammed and Busi Mhlongo. Arguably, those are some of the greatest names in South African roots music history. Three songs in, this person sitting next to me asked, “do you like this type of music because you’re trying to find yourself?”. The whole car went silent as my friends in the front seats and I tried to hold back our laughter. Seemingly, this was a sincere question.

I looked at this guy, and responded “wait, so this music only has value in the context of some kind of projection of an identity crisis? You don’t think that its value is inherent?” Of course in retrospect, this guy was making more of a judgement about me and whether I was “black enough to get it”, as opposed to the value of the music, but it got me thinking nonetheless. How and what are we accessing (in) music that has very particular cultural, spiritual and political intentions behind it? I’ll get back to this in a bit.

Fast forward a few years and Busi Mhlongo has now been pressed on vinyl for the first time, with her groundbreaking album, Urban Zulu reissued by Matsuli records, on the 10 year anniversary of her passing. If collecting southern African jazz and rare groove vinyl is your thing, then it’s unlikely that you haven’t heard of Matsuli. Their stable has been responsible for the reissue of albums by Bea Benjamin, Ndikho Xaba & the Natives, Batsumi and Moses Molelekwa to name a few. So when fellow vinyl collector, selector and journalist, Atiyyah Khan (El Corazon/Future Nostalgia) asked me to hop on Zoom for a discussion between her, Chris Albertyn and Matthew Temple (Matsuli), Uchenna Ikonne (Comb & Razor) and Calum MacNaughton (Sharp-Flat), I was curious.

Hosted by Africa Open Institute at Stellenbosch University and chaired by Stephanie Vos, the roundtable ambitiously entitled “Vinyl in Africa” was positioned as an online event part of Africa Synthesized; a conference exploring electronic music in, of and about Africa “pre-MP3”. Let me first begin by acknowledging how incredibly cumbersome the new but necessary virtual format of Zoom discussions can be; arguably more awkward, however, is the task of reviewing virtual happenings. Yet here we are:

Over the past decade or so, we have seen an increase in contemporary musicians from the African continent pressing their music onto vinyl. Similarly, there are many labels on and from the African continent that are pressing newly produced music onto wax. In an age of streaming, the vinyl format is emerging as not just a medium of sentimentality, but rather one that offers tactility and increased archiving possibilities. But this conversation was not about that. What was it about? Well, to be honest, I’m not so sure — perhaps this speaks in part to the curatorial incoherence of trying to squeeze what is in fact a complex subject into a strict 1 hour time allocation. 25 minutes in, we still found ourselves listening to speaker introductions. Despite what normative ethnomusicology and anthropology may have us believe, the politics around the production and consumption of African, and more broadly Black cultural production cannot be addressed in a neatly packaged unidirectional conversation; especially one that is not intentionally framed. (Even if said conversation is positioned as introductory.)

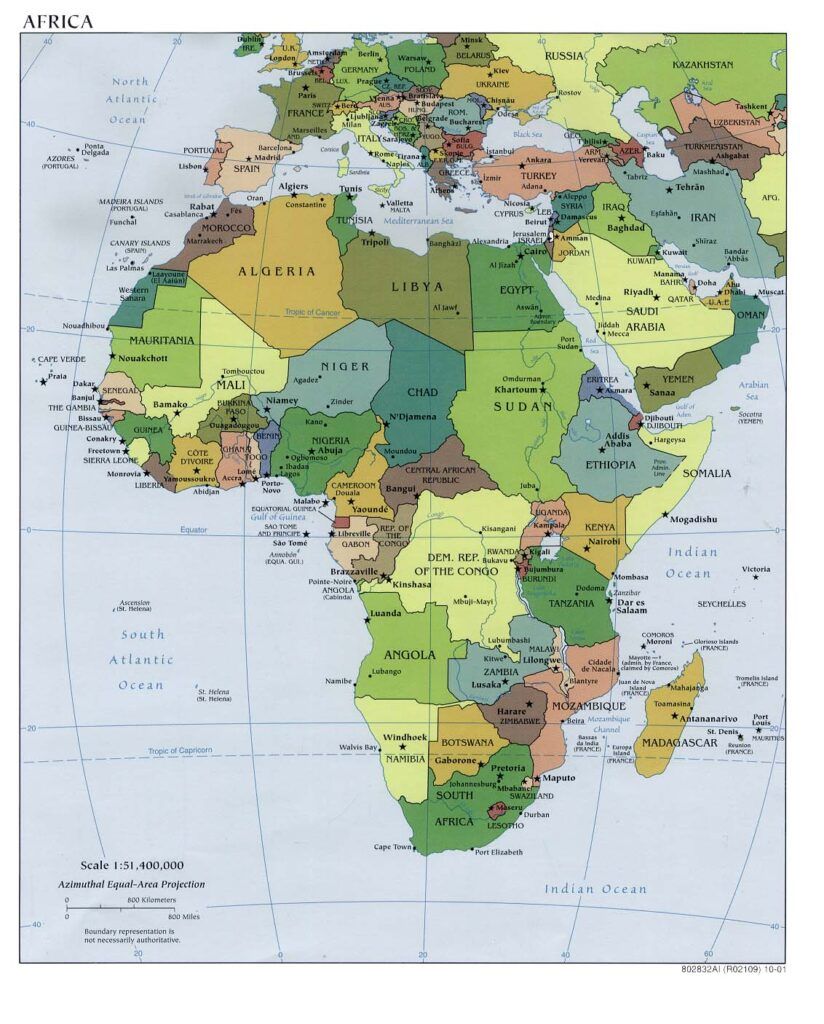

It needn’t have been this way, but “Vinyl in Africa” was, for the most part, focused on the culture of vinyl re-issuing. By default, this conversation then takes on a particular tone of nostalgia and immediately raises questions around archiving and cultural custodianship. Additionally, the term “Africa” was never really addressed with much specificity. Are we talking about vinyl labels in and from Africa, or simply African music pressed on vinyl? Furthermore, which Africa? Of course we could have chats about all of the above, but not in 30 minutes, nor in a single article. The answers to questions like these have significant consequences for how we address the ethics, politics and praxes of any given context. Thus, with no framing of these particulars in the symposium, there was little interlocution between panelists, and numerous unsaid assumptions and separate conversations occurring concurrently through the engagement. Of concern is that this lack of framing seems to undo the very agenda of the symposium, in that it runs the risk of recapitulating the dichotomy ever-present in sound studies, where the global North is aligned with (sound) technology, and the global South with (sound) culture.

A few years ago, on a visit to Addis Ababa, I came across an Ethiopian record dealer who quite subversively and amusingly sold severely scratched vintage records to ferengis (tourists) at exorbitantly high prices,. Now personally I love a harmless tourist scam. This was his own small act of rebellion, after an infamous Scandinavian almost cleaned Addis dry of mint Ethio-Jazz vinyl. At this point, it is not news that Westerners, either posted on the continent or in Euro-America, have been engaged in what Boima Tucker likens to the colonial ‘Scramble for Africa’, through the pillaging of African vinyl from Africa (and by extension African cultural resources). What’s important to note here are the ways in which the circulation of this vinyl mimics colonial trade routes, as it is set up for the consumption of either Western buyers (as the secondhand sale of these pressings mostly out-prices even the middle-class African collector) or Western audiences, as they are used to provide putatively ‘exotic’ samples in club DJ sets. Even more concerning is the way the inflated secondhand market of vintage vinyl completely leaves the artist on the continent out of the profit-chain; an acute observation raised by Chris Albertyn. Not unrelated are the ways in which Khan finds herself engaged in a sort of necessary repatriation of African music each time she travels to the West and finds our own music available in a disproportionate abundance.

Whilst there are Ethiopian-owned labels such as 1432 R who release music on vinyl, I have yet to come across any that are involved in the re-issue game. Most twentieth century vinyl of African music is reissued through white-owned European-based labels. What this means is that the heightened mobility that the act of reissuing is meant to afford the music and the artist is filtered through a Western aesthetic sensibility that is often ignorant of the historical context of the production. Consequently, what is deemed worthy of this mobility in this instance is very rarely what folks from the context may deem important.

Working out of Nigeria, Uchenna Ikonne has clearly witnessed his fair share of this dynamic, where Western buyers and thus labels have displayed a Tintin-esque obsession with Nigerian “funk” or afrobeat and boogie, whilst Fuji sounds, for example, have enjoyed a lot less attention in the Western re-issue market. Here, the music is often released in a compilation, without much archival thoughtfulness in the liner notes, and with many of the original musicians finding themselves embroiled in extremely exploitative licensing deals, drawing the short straw of exchange rates. Thankfully, this is where Ikonne has stepped in, curating multiple compilations and re-issuing albums that speak to his own aesthetic sensibility as someone who grew up around the music — whilst still unfortunately having to answer in some ways to Western markets due simply to matters of economics. Thanks to him, we know William Ezechukwu Onyeabor and his music.

Re-issuing vinyl, when there are no pressing plants on the continent, is expensive, and again the average African consumer is priced-out. In an interview with Afropop Worldwide, Ikonne suggests that Nigeria doesn’t have much of a nostalgia culture. “Nigerians are always looking forward”.

The conversation around the reissue of much of South Africa’s jazz however takes on a different tone. Much of our music has been produced under extreme political and social duress, and many of the prominent artists like Johnny Dyani and Dudu Pukwana produced records in exile. South African music-lovers are almost constantly engaged in a kind of necessary nostalgia and loss; which even finds itself emerging in the sounds produced by contemporary jazz musicians.

In her monograph, Black Metamorphosis, Sylvia Wynter advocates that the Black sonic as “the aesthetic/ethic principle of the gestalt” and thus central to the reconstitution of Black life. In her looking at rhythmic traditions throughout the Black diaspora, she draws attention to how the making and praxis of music — within the context of antiblack axioms — is underwritten by the “revolutionary demand for happiness” (McKittrick, 2016: 81). The very sociality, and mobility, of the Black sonic does the work of undoing the types of alienation that apartheid and coloniality demand. Theorists, like Chude-Sokei, Alex Weheliye and Fred Moten would agree. Hearing and listening and grooving to this music is a rebellious political act. Following from Katherine Mckittrick (2016: 81), “black waveforms” are themselves “rebellious enthusiasms” that undo racial confinement through their own kind of protracted agency. But folk who have been racialised by the apparatuses of white supremacy never needed academics to tell them this; the theory is in the music. To listen to and share this music is to be engaged in a simultaneous joy and pain…and loss. Of course this is simply brought into stark relief when placed against the context of exile, and the very recent history of outlawing particular black waveforms in apartheid South Africa.

Through this lens, bubblegum music also emerges as possessing an irreducible scream, as do the waveforms of Nigerian funk or Zambian rock — which seems to be the new focus of Calum MacNaughton’s Sharp-Flat label.

However it’s worth noting that he casually and uncritically uses the tags “electric tribal rock” and “afro-rock” on the label’s Soundcloud page[1]This page has subsequently been deleted. to describe Xoliso’s Shingwanyana.

At what point will rock produced by Black people simply exist without hyphenation…as if rock weren’t itself a Black musical tradition? Furthermore, can we please stop throwing around this word “tribal”.

And this brings me to my final frustration with the “Vinyl in Africa” dialogue. Ikonne’s archiving and re-issuing of music from his own context is not the same as the exercise that Matsuli and Sharp-Flat are engaged in. Of course, there is value to be found in what Matsuli does, in the curating of their stable beyond releasing albums that are just hard to find and economically viable, but by the reissue of rare albums that carry historical importance for music in the country.

Furthermore, they can be credited for their collaborative efforts with researchers like Atiyyah Khan, and family members of artists, who help to respectfully situate each album within the archive through extensive liner notes. However, no matter which way you look at it, there are ethical implications when white folk (even if they are South African) place themselves as agents in the mobility, and thus historical trajectory of Black music. Such ethical implications require more consideration than just the lip-service Vos let slide throughout the roundtable.

Good intentions are simply not enough, as the facts of how our music gets archived, and by whom, are embedded in a system of white ownership that has historically ripped Black and African persons of their humanity, whilst simultaneously consuming their production. The consequences to our collective cultural archives are deeply intimate and we cannot have these conversations about music as if the production and dissemination of Black aesthetics is void of these political implications.

To work with “the archive”, any archive, is to submerge oneself in a kind of reckoning with loss. It is a privilege and an honorto work with the archive pertaining to the socio-political history of others, especially in a context when much of it has been erased for the descendants of that history. Consequently the ethnographic tone around saving music from proverbial oblivion can no longer take the front seat in these types of discussions. Instead I’m far more interested in what more meaningful and sustained partnerships with curators, collectors and listeners of colour may look like at the label-level, and not just on an album-to-album basis. The age-old argument of not being able to find anyone qualified truly cannot stand in 2020.

| 1. | ↑ | This page has subsequently been deleted. |