All the photographs on this page are preserved in the Hidden Years Music Archive, Stellenbosch University.

In 1971, a sound system arrived in South Africa, the first of its kind, that made possible the development of a unique South African music story. The history of this sound system has largely fallen into obscurity even though it influenced most early music sound companies in South Africa.

To Woodstock and back again

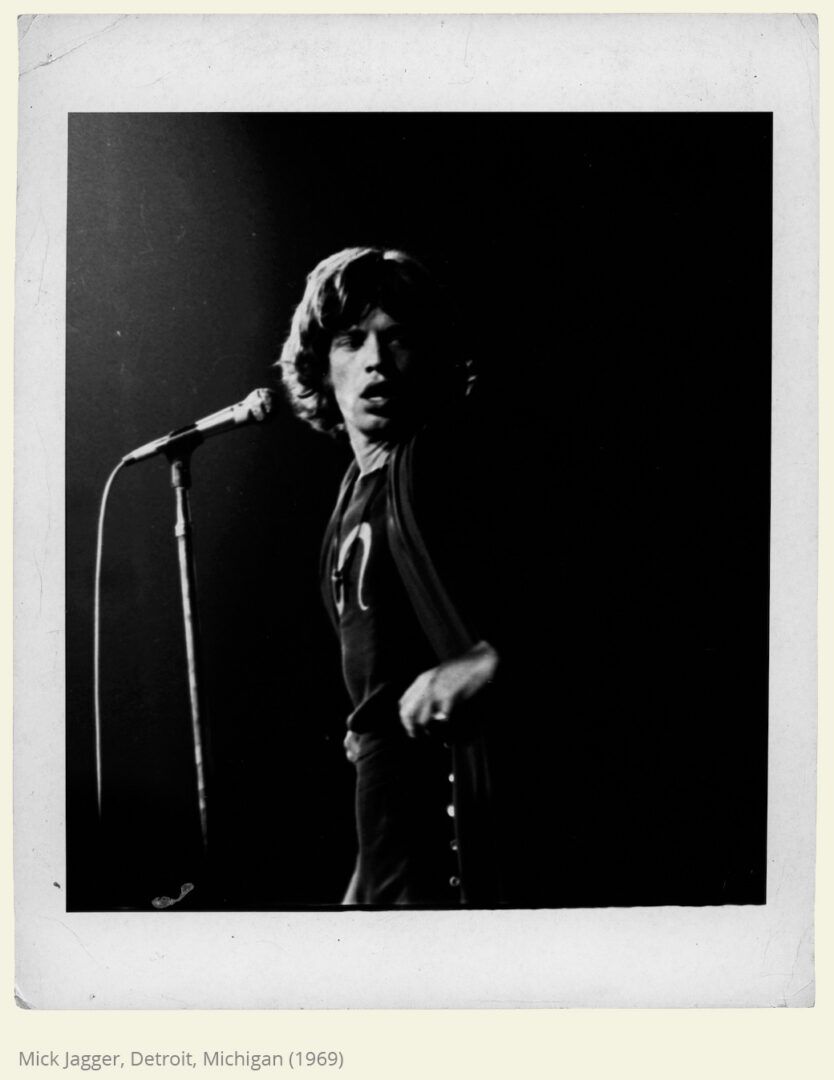

In 1969, David Marks an avid folk musician and song writer, left his day job as a blaster on the mines outside of Johannesburg to travel to America. This was made possible with royalties Marks earned from his international hit song, Master Jack recorded and released by the South African folk rock group Four Jacks and a Jill in 1967.[1]Master Jack was one of South Africa’s most successful international songs charting in South Africa (no.1), Canada (no.3), New Zealand, Malaysia, Zimbabwe, Australia and in the US on the Billboard 100 (no.18). R. Trewhela, Song Safari, a Journey through light music in South Africa, (The Limelight Press, 1980), p.76-77. The song has endured and is still regularly performed and played on the radio. In America, Marks found work as a roadie for the Boston based Hanley Sound company.[2]L. Lambrechts, Letting the tape run: The creation and preservation of the Hidden Years Music Archive, South African Journal of Cultural History 32(2), 2018, p.7.

Bill Hanley started his career at the Newport Jazz Festivals in the early 1950s. He gained experience and renown by providing sound reinforcement for the presidential inauguration of Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965 and several other festivals and events in America.[3]J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House: The Story of Hanley Sound (The University of Mississippi Press, 2020), p.84. By the time that Marks joined the company in 1969 they were doing the sound for major festivals and events including shows at Madison Square Garden, the Newport Folk and Jazz Festival, and in August that year, the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair.

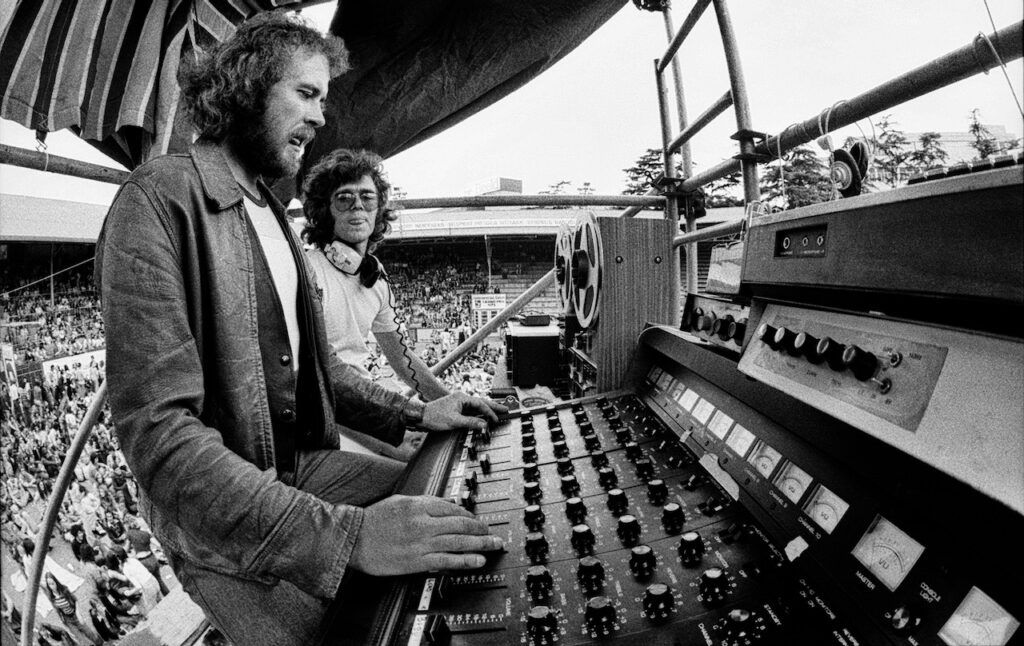

David Marks documented all of the events he attended in America with his Pentax Spotmatic 35mm camera. Photographs by David Marks.

Setting up the sound for a festival such as Woodstock was a big challenge. Kane notes that “in 1969 sound reinforcement equipment was not something you could just go out [and] purchase at a store. Either you made it, went without, or adapted”.[4]J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.228. Hanley custom designed the speakers and other essential equipment they were going to need and his crew set about building the “Hanley Sound Inc. (HIS) 410 lower-level and 810 upper-level speaker cabinets measur[ing] 7ft. x 3ft. x 4ft. each roughly weighing in at a whopping half-ton”. These speakers, known as the “Woodstock Bins,” came to be “as iconic as the festival itself.”[5]J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.255.

Hanley was an idealist noting that he wanted “to make the world a better place to live by making it easier to communicate. This is what Woodstock was all about for me”.[6]Bill Hanley as used in J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.297. This same idealism and the friendship that grew between Hanley and Marks, led Hanley to donate and ship part of the sound system that was used at the Woodstock Festival to South Africa.[7]L. Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.8. This system was intended by Hanley to be used by David Marks in the fight against the social injustices in South Africa by not using it to play to segregated audiences.[8]J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.297.

3rd Ear Music and Sound Company

Upon his return to South Africa in 1970, Marks took over the Directorship of the 3rd Ear Music Company, an independent record label and music publisher founded by Ben Segal and Aubrey Smith in 1967. The aim of the company was to “serve local musicians”, and “to produce and promote South African live-music performances that was not heard within the mainstream record and broadcast industries.”[10]National Research Foundation Grant, 2005, 3rd Ear During apartheid, the South African record industry was largely shaped by the government’s ideologically driven censorship protocols that banned material seen as “religiously offensive, politically threatening or morally problematic”.[11]M. Drewett, Shifty records in apartheid South Africa: Innovations in independent record company resistance, SAMUS: South African Music Studies 34/35, 2016, p.30. This determined radio airtime which in turn impacted sales, and musicians were required to tow the line in order to get record deals. 3rd Ear Music intended to serve alternative popular music in South Africa, the musicians who were rarely commercially successful and chose to live outside of the musical mainstream, often speaking out against the regime.[12]L.Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.8.

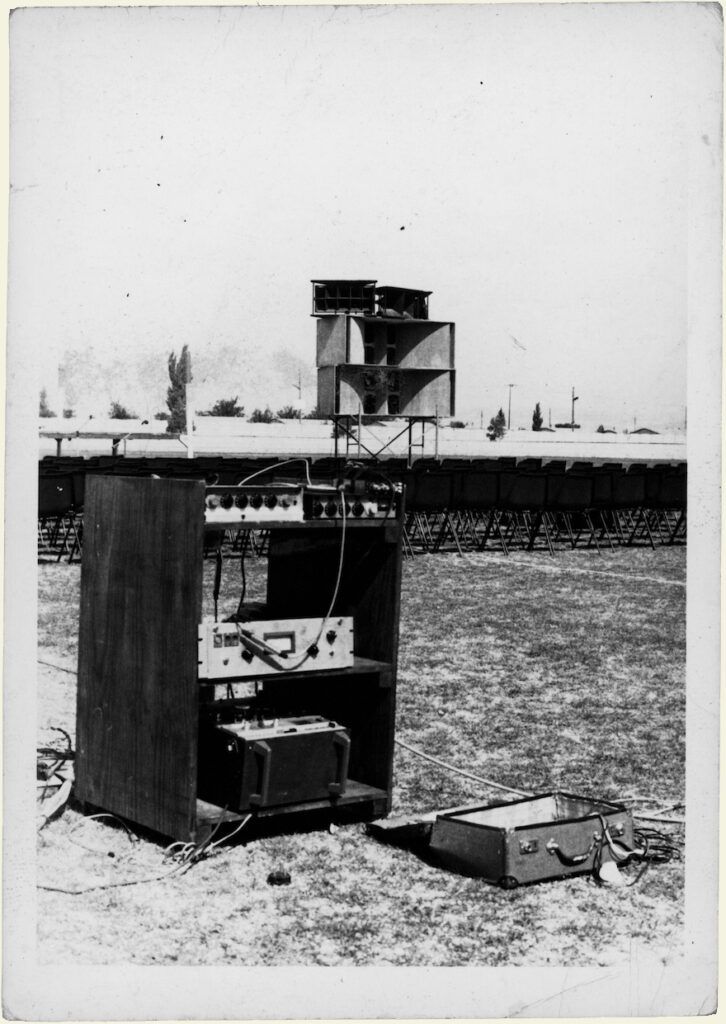

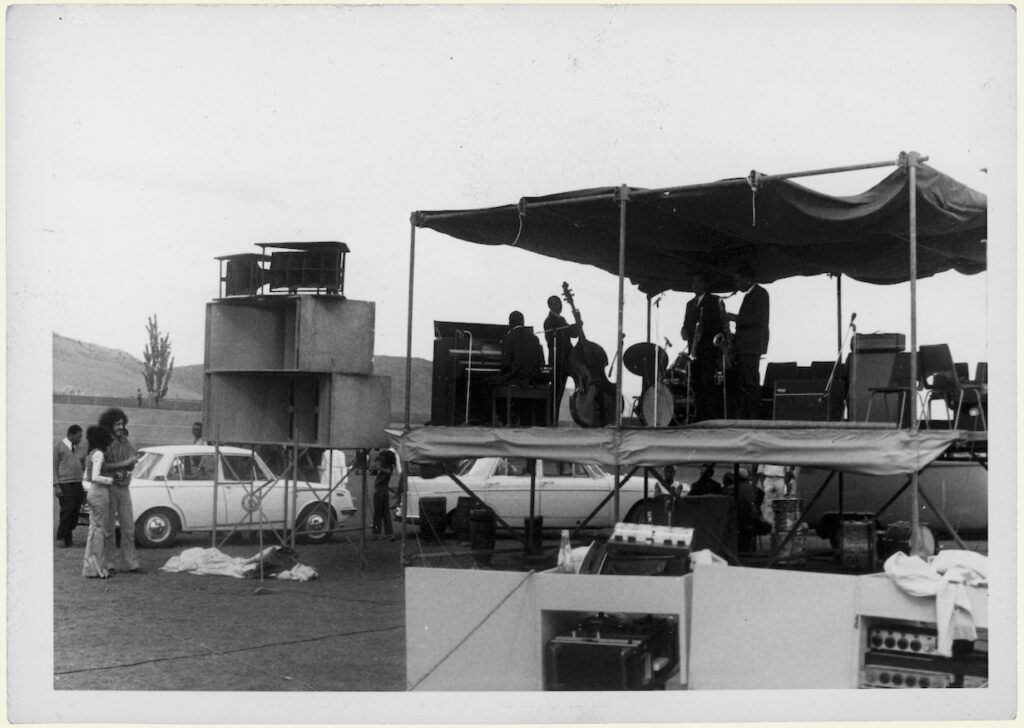

In 1971, the sound system donated by Bill Hanley arrived in South Africa. According to Marks, Hanley sent a remarkable amount of equipment that included “four loudspeakers each with four 15-inch JBL D140 woofers. The tweeters consisted of 4×2 cell and 2×10 cell Altec Horns. At the mixing end of the system were 3×4 channel rotation-pot Shure ME mixers, daisy-chained to give us the awesome capability of mixing twelve microphones all at once. We had one 10-band home-made graphic equalizer for the entire system and a Teletronix Limiter/Compressor our single most impressive and revolutionary bit of gear; all driven to distortion by a bunch of Crown D300 power amplifiers.”[13]David Marks as quoted in J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.297.

The cabinets, weighing half a ton each, were not shipped with the donation but rebuilt in South Africa by Timothy de Paravicini working for Altec at the time.[14]Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, April 10, 2017, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. With this sound system, the first of its kind in southern Africa, Marks established 3rd Ear Sound, a dedicated sound company with Don Williamson, and later with Toma Simons and Jürgen Brauninger.[15]Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, April 10, 2017, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection.

3rd Ear Sound played an important role in the functioning of the music company. Not only did it allow Marks a near monopoly in the business of sound reinforcement in the early 1970s South Africa, but Marks could also make recordings of live events through a desk feed of the system.[16]L. Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.8. These recordings are preserved in the Hidden Years Music Archive at Stellenbosch University. The preservation project is directed and managed by Lizabé Lambrechts. These recordings grew into a unique collection of more than 3000 reel-to-reel tapes and 4000 cassette tapes of recorded live music. These recordings are being preserved, digitised and made accessible through the Hidden Years Music Archive project at the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation, Stellenbosch University.[17]L.Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.9.

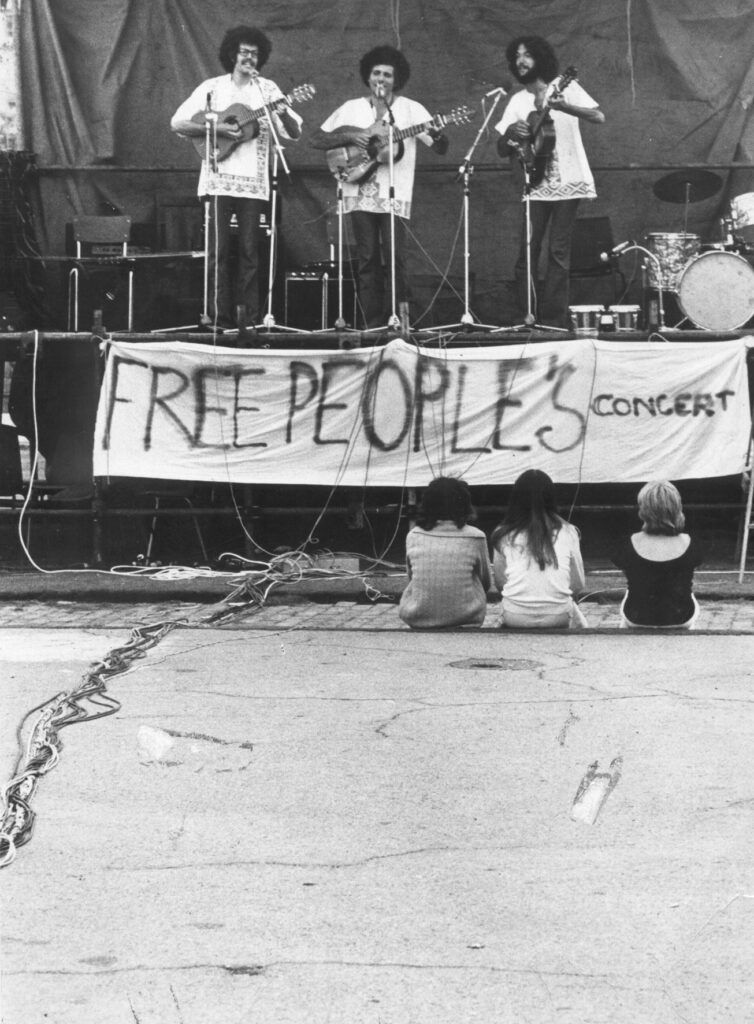

Through the work of Marks and his team, the Woodstock Bins quickly became a regular feature at festivals and large concerts in the 1970s, such as folk festivals organised by the South African Folk Music Association, township concerts and events, international touring musicians and the annual Free Peoples Concerts, one of the first multi-racial events Marks set-up with the sound system. These concerts were conceptualised as an annual event that would provide “a platform for local musicians of all races to play before a multi-racial audience,” and “get people together to experience alternative South African music in a free environment irrespective of race.”[18]Hidden Years Music Archive, Documentation Center for Music, Stellenbosch University (hereafter Hidden Years). David Marks Collection. Digitised item: The ‘Free Peoples’ Spirit. File extension: HYMAP_Archive_Newsclip_LiLa_Photographs_Free_ Peoples_Concert In spite of facing cancellations, sabotage, permit battles and censorship at the hand of the apartheid government, the concerts continued and ran from 1971 to 1992 at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Musicians from all over South Africa performed at these events ranging from country, folk, jazz, blues, funk, alternative rock musicians to punk groups in the 1980s.[19]Hidden Years. David Marks Collection. Newspaper cutting: R. Christie, State edict ends the Wits ‘free concerts’, The Star, Friday, 2 April 1976. This history is currently being developed into a book by Lambrechts.

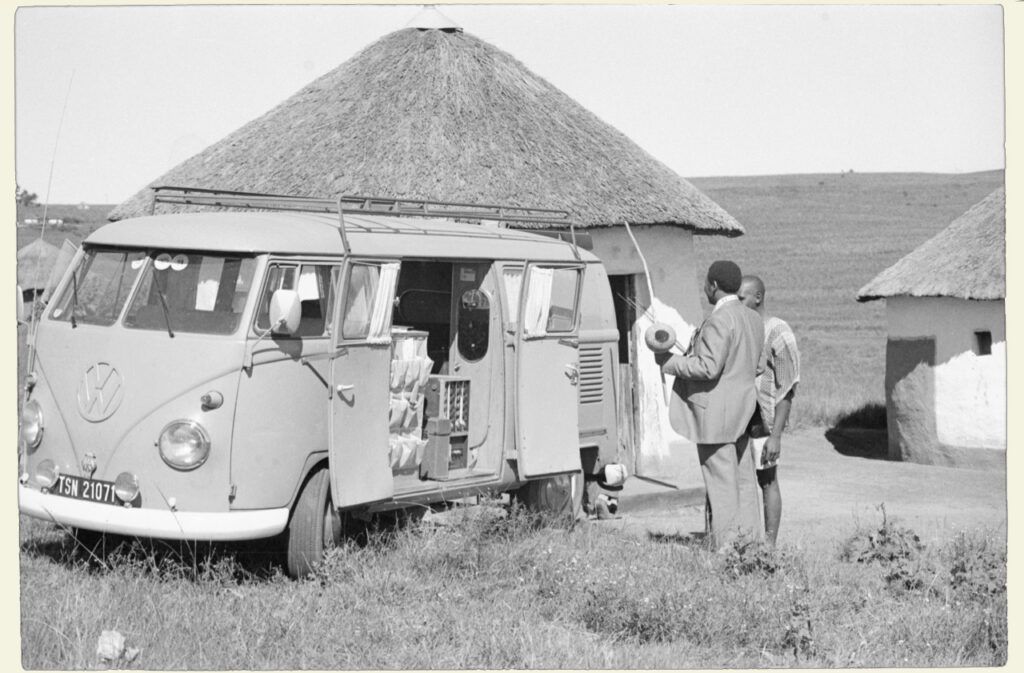

The Woodstock sound system allowed Marks to build one of the first mobile recording studios in South Africa in order to record live events and music on location. In 1972, Marks fitted his 1962 Teardrop Volkswagen Kombi “with the Rotary Pot Sure Mixers he received from Hanley Sound and placed monitor speakers behind the front seats. This allowed him to mix from inside the Kombi”.[20]L.Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.10. With his recording studio Marks went to the Transkei to record the traditional isiXhosa bow musician, Madosini Latozi Mpahleni.

The sound system was also used for international touring musicians including Brook Benton (1971), Percy Sledge (1972), and Chase (1972). By performing in South Africa, these musicians were breaking the cultural boycott. The boycott was instituted in 1968 by the United Nations general assembly to “prevent South Africa from having cultural, educational and sporting ties with the rest of the world”.[22]A. Waggie, ’It’s just a matter of time’: African American musicians and the Cultural Boycott in South Africa, 1968-1983, Masters thesis (Stellenbosch University 2020), p.2-3. The boycott was intended to prevent international musicians touring South Africa as “it was believed that visits by popular musicians legitimised apartheid and oppression”.[23]A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.2-3. Nevertheless, a number of musicians toured South Africa using South African promoters, sound companies and supporting musicians.[24]For a list of South African musicians who performed with international touring musicians in the 1970s see A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time’ (2020).

Marks pointed out that while he never promoted or produced these shows, he did the sound in order to make a living. He notes that even though he supported the cultural boycott, it was “awkward for those of us whose livelihoods depended on music and events in Southern Africa, and who had no choice but to stay. However, by staying, and doing whatever was possible to bring change – without risking the meagre income of musicians who were not apartheid apologists – was a sensitive balancing act.”[25]Correspondence L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, 28 July 2020. Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection.

Similarly, various musicians who supported the fight against apartheid and the cultural boycott accepted the work that these tours offered. The Brook Benton tour was for example supported by Cocky Tlhotlhalemaje, Ronnie Madonsela and Count Wellington Judge.[26]A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.111. Ashrudeen Waggie pointed out that “many South African musicians who performed with these American musicians did so to survive financially and received publicity both locally and internationally. They were cornered both from South African censorship, not being able to release the music they wanted locally, and the international boycott that restricted them from exposure beyond the boundaries of South Africa.”[27]A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.44.

For this reason, various musicians who supported the cultural boycott did not believe it should be imposed on South African musicians.[28]M. Drewett, The cultural boycott against apartheid South Africa: A case study of defensible censorship? In Popular Music Censorship in Africa edited by M. Drewett & M. Cloonan (USA: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006), p. 31 However, Marks argued that the boycott could be used to effect change in South Africa for this very same reason. As a policy, the Cultural Boycott “sought to restrict the distribution of music in South Africa”.[29]A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.2. For more information see also the work of M. Drewett, An Analysis of the Censorship of Popular Music within the Context of Cultural Struggle in South Africa during the 1980s (Unpublished PhD thesis, Rhodes University, South Africa, 2004). Marks made numerous appeals to local and international record labels and the South African Broadcasting Corporation to promote local music. He pointed out that “our local recorded music and musicians were being denied airplay, but the airwaves were filled with international anti-apartheid boycotting pop stars,” who were gaining publicity and record sales from their pious stands.[30]Correspondence L.Lambrechts with D. Marks, 28 July 2020. Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. His appeals were not successful, the apartheid censorship mechanisms and financial gain for international and local record labels being too powerful.

Some groups who toured South Africa in the 70s faced scrutiny upon their return, for example the Chicago jazz group, Chase. However, consequences for artists who toured South Africa against the boycott only started to gather momentum in the 1980s after the publication of the first annual registry by the United Nations of all international entertainers that performed in South Africa.[31]United Nations Centre against Apartheid, Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa (United Nations, October 1983).

Marks set up the sound for Chase who opened their tour at the Johannesburg City Hall on 3 January 1972, after which they performed in Durban on 7 January and in Cape Town on 13 January. The Woodstock Bins had to be transported between these cities. Marks remembered the drive in an interview.

Transcription of Interview:

So, the horns were strapped to the roof of my Volkswagen Kombi, and I drove through one of those swarms of locusts. It’s the most unbelievable experience, we went through two locust storms in the Karoo, and they just come, you can’t believe it, you can’t see the road. And a whole lot of them got stuck, I should have covered the bloody speakers, how stupid was I? I always regretted that years later. But I thought that the horns, a speaker with a driver on the back – it’s got a little mesh, but none of those meshes were working, so the locusts that got into the horns got straight into the diaphragms. When we fired up this big system, and everybody was so impressed with it, and we had had a good tour with Chase so far, they were very impressed with the sound for what we had which was very rudimentary, the Hanley ME mixers, the limiter, the crossover – we turned on the sound and all of a sudden there was nothing. All we had was the low end, the bass bins. It was a disaster, people were screaming, they wanted their money back. Walking out. The next day we sort of got it right, what we did was we drove the bass bins full range, so we didn’t have horns. We borrowed a few from someone in Cape Town, I can’t remember who.[32]Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, August 14, 2015, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection.

Later that same year the sound system was on the road again, this time on a southern African tour with Percy Sledge and supporting musicians including The Miracles (a seven-piece soul group from Newlands, Johannesburg), Richard Jon Smith and Chris Schilder with the Cape Town Horn Section. The ambitious tour, promoted by the Sagittarius Management Company owned by Clive Calder and Ralph Simons, started in Mozambique and then moved to Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia and Angola.[33]For a detailed account of this tour as well as other African American soul musicians who visited South African in the 1970s see A.Waggie, ’It’s just a matter of time’: African American musicians and the Cultural Boycott in South Africa, 1968-1983, Masters thesis (Stellenbosch University 2020).

The tour made use of two modes of transport: A Dokota DC3 airplane that was reconfigured with the seats removed on the one side to make space for the sound equipment and the musicians travelling on the other side,[34]Interview L.Lambrechts with D. Marks, August 17, 2011, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. and a truck to transport the sound and lights crew and the rest of the equipment that couldn’t fit onto the plane including the 6x6x4 foot 500lb JBL and the Altex Woodstock Bass Bins and some of the Crown and Macintosh power amps.[35]A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p. 77. Hidden Years. David Marks Collection. Document: List of Equipment to be used on the “Percy Sledge” tour of southern Africa, Box 316. The system suffered lots of damage on the road and had to be fixed in Harare, Zimbabwe, before the tour could continue to Malawi, Victoria Falls, Angola and back to Zimbabwe.

Changing hands

By the mid-1970s Marks gave over the management of the sound system to Jeff Lonsteen. Lonsteen, who had established Coliseum Acoustic in 1972, a company selling Altec sound equipment in Johannesburg, would manage the business side of renting out the system while Marks and his team would do the sound set-up and make the recordings.

The system was also rented out to ProSound, a sound company established by Dennis Feldmann, Terry Ackers, Clive Delaware and Simon and Tony Oats in the mid-1970s. Dennis Feldmann and Terry Ackers started the Musicians Sound Centre (MSC) in Hillbrow, Johannesburg, selling various electronic gear, while Clive Delaware made Specialist Audio mixers and amplifiers in his garage. Marks was increasingly occupied with booking musicians and organising shows for the number of coffee clubs he managed and set up an arrangement with ProSound. They could take over the Woodstock Bins as long as they would book him to set up the system for gigs.[36]Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, April 10, 2017, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection.

In 1983 Marks moved to Durban with his family, and his story with the Woodstock bins ends.

Transcription of interview:

Lizabé Lambrechts (LL): Do you know what happened to that sound equipment?

David Marks (DM): Ya, then, the ProSound thing, when ProSound started importing the new type of gear in the 70s, before I left for Durban, a guy called Jackson Morely, the guy who was one of the promoters for the Brook Benton show earlier, he was from Daveytown, and he took over the Bins, or they sold it to him or gave it to him, unbeknown to me at the time. But I’d just heard, I was in Durban by then, that Jackson was putting on these big shows with the Bins, they were still active. Right through the 80s.

LL: And after that, your story ends with the Woodstock Bins right?

DM: Ja.

LL: Do you know what happened after that?

DM: No. Other then Jackson Morely pulling them out, see ProSound didn’t really need them because ProSound had become very big and they were importing Electro Voice and they became the Electro Voice agents, which was the new technology.

LL: Ja, we have brochures of that in the archive. It would be something to find the Woodstock Bins!

DM: I know…I wonder what happened. Maybe they are in somebody’s garage…gheez, they are huge!

LL: You think they probably threw it away?

DM: Well…you know they were very strong. They were made out of Marine Ply and all that, but then the speakers would have by now, unless if they replaced them…we’d often have to replace the diaphragms of the 15 inch because they would either, like on the Percy Sledge tour…

LL: Full of bugs

DM: Ja, and sand and all that…[37]Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, April 10, 2017, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection.

Whether the system is lying around in someone’s backyard, was melted down for metal or sent back to the Boston suburb of Medford, “still intact and slightly worn” as John Kane would have it,[38]J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.298. the Woodstock Bins left an indelible mark on the South African music landscape. David Marks used this system to promote alternative popular music in South Africa, music that would probably not have been noticed had it not been for Marks. Through his dedication to document these events, his archive tells South Africa’s story from another perspective, one which is little known today, of musicians and songwriters, white and black, who made music together in spite of the political situation at the time.

For the record collection and archive built on the legacy of the Woodstock Bins by David Marks visit the Hidden Years Music Archive or contact Lizabé Lambrechts lambrechts@sun.ac.za.

| 1. | ↑ | Master Jack was one of South Africa’s most successful international songs charting in South Africa (no.1), Canada (no.3), New Zealand, Malaysia, Zimbabwe, Australia and in the US on the Billboard 100 (no.18). R. Trewhela, Song Safari, a Journey through light music in South Africa, (The Limelight Press, 1980), p.76-77. The song has endured and is still regularly performed and played on the radio. |

| 2. | ↑ | L. Lambrechts, Letting the tape run: The creation and preservation of the Hidden Years Music Archive, South African Journal of Cultural History 32(2), 2018, p.7. |

| 3. | ↑ | J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House: The Story of Hanley Sound (The University of Mississippi Press, 2020), p.84. |

| 4. | ↑ | J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.228. |

| 5. | ↑ | J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.255. |

| 6. | ↑ | Bill Hanley as used in J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.297. |

| 7. | ↑ | L. Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.8. |

| 8. | ↑ | J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.297. |

| 9. | ↑ | J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.225. |

| 10. | ↑ | National Research Foundation Grant, 2005, 3rd Ear |

| 11. | ↑ | M. Drewett, Shifty records in apartheid South Africa: Innovations in independent record company resistance, SAMUS: South African Music Studies 34/35, 2016, p.30. |

| 12. | ↑ | L.Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.8. |

| 13. | ↑ | David Marks as quoted in J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.297. |

| 37. | ↑ | Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, April 10, 2017, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. |

| 16. | ↑ | L. Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.8. These recordings are preserved in the Hidden Years Music Archive at Stellenbosch University. The preservation project is directed and managed by Lizabé Lambrechts. |

| 17. | ↑ | L.Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.9. |

| 18. | ↑ | Hidden Years Music Archive, Documentation Center for Music, Stellenbosch University (hereafter Hidden Years). David Marks Collection. Digitised item: The ‘Free Peoples’ Spirit. File extension: HYMAP_Archive_Newsclip_LiLa_Photographs_Free_ Peoples_Concert |

| 19. | ↑ | Hidden Years. David Marks Collection. Newspaper cutting: R. Christie, State edict ends the Wits ‘free concerts’, The Star, Friday, 2 April 1976. This history is currently being developed into a book by Lambrechts. |

| 20. | ↑ | L.Lambrechts, Letting the tape run, p.10. |

| 21. | ↑ | R. Haslop, David Marks. Perfect Sound Forever online music magazine presents…, (Online, 2010). |

| 22. | ↑ | A. Waggie, ’It’s just a matter of time’: African American musicians and the Cultural Boycott in South Africa, 1968-1983, Masters thesis (Stellenbosch University 2020), p.2-3. |

| 23. | ↑ | A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.2-3. |

| 24. | ↑ | For a list of South African musicians who performed with international touring musicians in the 1970s see A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time’ (2020). |

| 25. | ↑ | Correspondence L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, 28 July 2020. Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. |

| 26. | ↑ | A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.111. |

| 27. | ↑ | A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.44. |

| 28. | ↑ | M. Drewett, The cultural boycott against apartheid South Africa: A case study of defensible censorship? In Popular Music Censorship in Africa edited by M. Drewett & M. Cloonan (USA: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2006), p. 31 |

| 29. | ↑ | A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p.2. For more information see also the work of M. Drewett, An Analysis of the Censorship of Popular Music within the Context of Cultural Struggle in South Africa during the 1980s (Unpublished PhD thesis, Rhodes University, South Africa, 2004). |

| 30. | ↑ | Correspondence L.Lambrechts with D. Marks, 28 July 2020. Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. |

| 31. | ↑ | United Nations Centre against Apartheid, Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa (United Nations, October 1983). |

| 32. | ↑ | Interview L. Lambrechts with D. Marks, August 14, 2015, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. |

| 33. | ↑ | For a detailed account of this tour as well as other African American soul musicians who visited South African in the 1970s see A.Waggie, ’It’s just a matter of time’: African American musicians and the Cultural Boycott in South Africa, 1968-1983, Masters thesis (Stellenbosch University 2020). |

| 34. | ↑ | Interview L.Lambrechts with D. Marks, August 17, 2011, Melville Kwazulu-Natal. Oral History Project, Hidden Years Music Archive, Lizabé Lambrechts Collection. |

| 35. | ↑ | A.Waggie, ‘It’s just a matter of time,’ p. 77. Hidden Years. David Marks Collection. Document: List of Equipment to be used on the “Percy Sledge” tour of southern Africa, Box 316. |

| 38. | ↑ | J. Kane, The Last Seat in the House, p.298. |