Colonialism had an impact on the way Africa was studied and documented. The creation of sound archives corresponded with the increase of ethnographic study of “tribal” societies. These studies were led by the disciplines of anthropology and musicology, which were beginning to establish, in academic terms, a discourse on African culture,[1]See Mudimbe, VY (1991). The Invention of Africa. Indiana: Bloomington Press; Agawu, Victor Kofi (2003). Representing African Music. New York: Routledge. music and performance.

Foremost among those who led the race for preserving and studying African music was Devonshire-born, Hugh Tracey. Tracey began taking an interest in African music in 1921, during his early days in Zimbabwe, where he had come to farm tobacco with his brother. Born in 1903, just three years after Princess Magogo— the expert in Zulu royal song who he would later record — Tracey was one of eleven children born to a family in Devon, Britain. When he was seventeen, Tracey moved to Zimbabwe with his brother in 1920. Here he first had the chance to personally witness African traditional performances. Living with the Karanga people in Zimbabwe, he learnt to speak Karanga, and started notating the songs he heard. Tracey was immediately convinced of the importance of music in the lives of the people. This was despite the dismissive attitude of the colonial settler community in the area. Finding notation inadequate, Tracey ventured into recording technology. He relates his experience as follows:

The history of this collection of authentic African music, songs, legends and stories is in many ways a personal one. It dates back to the early 1920s when I first sang and wrote down the words of African songs I heard in the tobacco fields of Southern Rhodesia [now called Zimbabwe]. Several years later (1929) I made a number of discs with a visiting recording company (Columbia, London) when I took fourteen young Karanga men with me to record in Johannesburg, five hundred miles south. These were the first items of indigenous Rhodesian music to be recorded and published. Shortly afterwards several of these items were used by John Hammond of CBS, at Carnegie Hall in New York as preliminary music to his program on the historic occasion when he presented on the stage, for the first time in that city, the music and the personnel of a number of southern Negro bands.[2]International Library of African Music (refer to discussion further on).

From Tracey’s recollection, it becomes clear that the collection and archiving of music in Africa was not only an academic exercise, but was strongly linked with commercial interests of recording companies. It must be kept in mind that, throughout the world, the 1920s was a period of expansion in terms of availability of sound reproduction technologies.

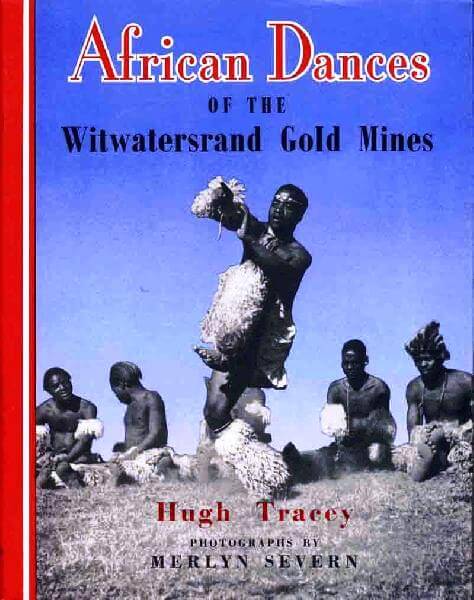

This paper revisits Hugh Tracey’s African Dances of the Witwatersrand Gold Mines (1952), which is now considered an important book in the emerging study of music in Africa. The subject matter of the book emerged out of Tracey’s field recordings in the Witwatersrand gold mines. From this beginning, Tracey went on to conduct field recordings all over southern Africa and many regions in central and east Africa.

Historical Background: Recording & Preserving Sound

Between the First and Second World Wars, the United Kingdom was a major centre for the recording and manufacture of gramophone records. But from the onset of the enterprise in the 1890s, recording was understood as a global phenomenon. There was an interest in recorded sounds from all over the British Empire. In 1912, recordings of Swazi chiefs who visited London in the early 1900s were distributed and sold internationally. In addition, recording technicians were sent on expeditions to capture Afrikaans and other traditional folk musics of Africa that were advertised and sold as ‘Native Records’ to global audiences.[3]Cowley, John (1994). “Recordings in London of African and West Indian Music in the 1920s and 1930s,” Musical Traditions. 12, 13-26.

As recordings began to reach wide audiences, scholars like Austrian Erich Hornbostel (who had never been to Africa) began to use these recordings to construct a theory about African and oriental music. He created a system of classifying musical instruments (liveabout.com) based on the sounds it produced. In 1928, Hornbostel published an article called African Negro Music. In the article he alerts his readers of his fears “that the modern efforts to protect culture are coming too late,” and that the true African music is already disappearing. Hornbostel goes on to urge for the recording “by means of a phonograph” of African music for otherwise “we will not learn what it even was”.[4]Hornbostel, Erich M von (1928). “African Negro Music,” Africa. 1:60. What enabled Hornbostel to construct his ideas about Africa music were recordings themselves, in the growing repositories of sound archives and exhibitions of musical instruments in the museums and universities of major European cities. Following Hornbostel’s investigation, scientific collections of music instruments and sound archives began to appear. To note a few, the Lautarchiv (some of whose sound archives were captured from prisoners of war in German concentration camps during the First World War) and Musikinstrumenten-Museum Berlin, the Kirby Collection (now housed at the University of Cape Town’s College of Music and some parts at Museum Africa).

But many of the collections were inspired by commercial interests as companies like the British Gramophone Company and subsequently African-based companies like Gallo Music took hold of the market. Gallo Music started out recording music performed by miners from all over southern Africa (including Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, to mention a few) who would congregate at the Witwatersrand gold mines (Johannesburg) in the 1920s and 1930s.[5]See Allen, Lara (2007). “Preserving a Nation’s Heritage: The Gallo Music Archive and South African Popular Music,” Fontes Artis Musicae. 54/3, 263-279. Gallo eventually employed Hugh Tracey for this role, who became the leader of African music archiving. What started as the African Music Transcription Library in Roodepoort, Johannesburg eventually grew to become the International Library of Africa Music (to be discussed further on).

Sound Preservation in the Mines

Tracey’s achievements in the archiving of sound in Africa are undoubtable. But his contribution must also be understood within the context of the tribing of African populations that was happening at the same time. Tribing was an ideology that preached that all African people belong to specific tribes, and must be kept in those tribes for their development.

The term tribing speaks to the activity, or doing, in how African populations were named into distinct tribes, and instantiated as such through all kinds of mechanisms of governance, knowledge production, commercialism. Tribing speaks to the effects of ideas about tribe in how we think about the past. It is concerned with how a domain of thinking about African cultural repertories developed in a way that emphasizes fixity, rather than progressive human development; in short, a timeless culture. [6]Hamilton, Carolyn & Leibhammer, Nessa (2016). “Introduction,” Tribing and Untribing. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press, 13-15.

The way tribing translated into Tracey’s work was in his dismissal of missionary and city-inspired styles of music, and overt promotion of what he considered traditional African music. He recorded the music he believed was under the threat of being lost. Seldom did he give jazz or marabi, for example, the same attention as styles like dingaka or ingoma. He was often derisive towards those who saw themselves as custodians of such contemporary styles. The ‘New African intellectuals’[7]‘The New African Movement,’ Accessed 18th June 2018 were one class who during the 1920s-1940s would have chosen to self-identify with the contemporary styles of choral music and jazz, amongst others. Cultural critic, Walter Nhlapo wrote as follows as in 1945:

But we deserve the heavier art of Caluza, Bokwe, Tyamzashe, Mohapeloa and others. These works demand concentrated attention and frequent repetition before digestion is completed, and even then at each new hearing reveal some fresh facets, some nuance, some subtlety that had escaped previous notice. It is in this varied music, I feel certain, lies the spirit of both old and new Africa.[8]“SABC Bantu Broadcasts”, Umlindi 4th August 1945.

The composers, Nhlapo mentions here—Caluza, Bokwe, Tyamzashe and Mohapeloa—were the leading innovators of new musical forms. And as the last sentence of Nhlapo indicates: these African composers were concerned with the spirit of both the old and the new, and were thus consciously absorbed in the task of elaborating African modernities through their art. At this time, the cultural imagination of the African middle-classes was evolving from church halls and the mission schools to a concert-tradition. Within these middle-class gatherings developed a distinct repertoire of musical performance. The music no longer comprised just Western hymns, but increasingly, a fusion of African traditional singing with ragtime tunes — derived from the minstrel songs and British provenance music halls songs which were sold as sheet-music at shops in the major towns.[9]Erlmann, Veit (1991). African stars: Studies in black South African performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 123. Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa for instance, and to some extent Reuben Caluza, wrote syncopated numbers in the 1930s and 1940s that were clearly jazz-band inspired.[10]See Lucia, Christine (2011). “Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa and the Heritage of African Song,” African Music. 9/1, 56-86. Although confined to four-part singing, the tunes were groovy, with dance steps involved.

Many of the African composers did not necessarily resent tradition and yet they respected Tracey’s perspective. Mohapeloa, for one, was a modern African composer par excellence.[11]“SABC Bantu Broadcasts”, Umlindi 4th August 1945. He wrote in his native language of seSotho, but his music circulated well among choirs and song-groups all over.[12]Mohapeloa, J P (1951). ‘Preface’ in Khalima-Nosi tsa ‘Mino Oa Kajeno : Harnessing Salient Features of Modern African Music. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. So much so that he was one of the three African composers who agreed to join Tracey’s African Music Society (AMS) in 1947. AMS’s goal was to preserve and study traditional music. Tracey had a special category for ‘African Members’—that was separate from ‘Members’ who were white. This special categorization appeared as a slap in the face of university-trained composers such as Caluza and Mohapeloa. Mohapeloa had studied music under Percival Kirby at Wits University, who was also a ‘Member’ of the AMS.[13]See “A: Minutes & Correspondence of African Music Society,” 2nd February 1949, P R Kirby Collection, BC750/A, Manuscripts & Archives Department, University of Cape Town; “List of Members,” 30th April 1948, P R Kirby Collection, BC750/A, Manuscripts & Archives Department, University of Cape Town. Certainly, Mohapeloa understood his own craft as preserving Sotho music rather than being ‘pseudo-European’, as he composed songs using traditional melodies.[14]See Lucia, Christine (2011). “Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa and the Heritage of African Song,” African Music. 9/1, 67-80. But the special (if not demeaning) designation within AMS did not seem to diminish Mohapeloa’s regard for Tracey.

When Mohapeloa made an application to the Lesotho government for a study tour grant in the 1960s, he put Tracey’s name down as a referee in the application. He wanted to explore music composition in England, Germany, Kenya and the United States. The Lesotho government then sent his application to Tracey for expert review. Tracey, however, dismissed the study on the grounds of its merits to the composer. He said that the study would “be altogether confusing for him, and indeed might undo any good work which he undertook on the African continent.” He suggested that Moheloa:

first becomes steeped in the music of Africa, from both a scientific and artistic point of view […] freed from his present leanings toward the mixing of African and European musics in his compositions.[15]International Library of African Music’s Hugh Tracey correspondence files, cited in Coetzee, Paulette (2014). Performing Whiteness: Representing Otherness: Hugh Tracey and African Music. Phd thesis, Rhodes University, 83-88.

So it would appear that over twenty years into his career, Tracey’s views had not changed. This is despite him having gone deeper in the recording and preservation of music in Africa after his tenure at the SABC (after 1943). Tracey’s musical preferences placed him at loggerheads with influential members of the New African intellectual movement at the time, including journalist HIE Dhlomo and Secretary of the Zulu Cultural Society, Charles Mpanza.[16]See ‘Chapter 10’ in Mhlambi, Thokozani N (2015). Early Radio Broadcasting in South Africa: Culture, Modernity & Technology (Doctoral Thesis). University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

On the other hand, the mining houses, state broadcaster and recording companies all at some point or another supported Tracey’s archiving work, and approved of his ideas. In those circles where Tracey’s ideas were endorsed, things went on almost oblivious to the articulations of those who held different views about the development of African culture, music and performance. Tracey’s tribal ideas could not have been at variance with those at the helm of the institutions of mining, broadcasting and recording. The sedimentation of tribal ideas in the white imagination in South Africa took place over a long time. Tracey’s project, arising at the time it did in the history of sound reproduction, represented a particular vision of the sound archive in Africa. It was characterized by a great emphasis on education (he established the African Music Society, International Library of African Music (ILAM), African Music Textbook Project, amongst others). Tracey’s role became influential in the constitution of a field of study, that of traditional African music; a field which would rely on sound archive as evidence.

One could say that Tracey was deeply concerned with collecting sound material. He used practical tools, recording devices, field notes, in order to create his collection. The concern for collecting superseded his interest in scholarly writing; and because of his practical approach he was often distrustful of musicologists who were studying African music only in a theoretical sense, without equal emphasis on performance and active participation.[17]Nketia, J H Kwabena (1986). “African Music and Western Praxis: A Review of Western Perspectives on African Musicology,” Canadian Journal of African Studies, 20/1, 39; Tracey, “The State of Folk Music in Bantu Africa,” 5. As a result, even in this book African Dances of the Witwatersrand Gold Mines, Tracey writes only the introduction, and then lets the photographs do the rest of the communication.

Of course, as we experience Tracey’s book today, in the 21st century, we are extremely aware of the institutional archive underpinning the spread and interest in the author’s contributions; that is the archive known as the International Library of African Music (ILAM) which is housed at Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape. ILAM is one of the most significant repositories of African music in the world. It preserves thousands of sound recordings dating as far back as 1929.[18]See Amoros, Luis Gimenez (2018). Tracing the Mbira Sound Archive in Zimbabwe. New York: Routledge, 1-3. There is therefore an interdependency between the text African Dances and the site-specific archive of ILAM, which informs the general contemporary discourse on how Tracey is understood today. Those who find the book first may very well end up visiting the site-specific archive, and those who come across the archive may very well end up purchasing a copy of this book, or Tracey’s many other books, in an effort to understand the work better.

Leo Owles, in recording room at ILAM, Msaho, Roodepoort. © ILAM Photographer. International Library of African Music. Makhanda.

Sound Technology as Evidence, Musicology and Anthropology

Looking at the beginnings of musicology (musikwissenschaft) as a discipline in the 1880s, Bruno Nettl shows that from the very first publication of the earliest musicology journal, there were inclusions of studies of folk music and non-European musics, even though they did not comprise the majority of the articles published. He writes:

I believe that what was crucial in making a holistic musicology out of music history was the addition of the kinds of work done by ethnomusicological studies, in the sense of an interculturally comparative perspective, a relativistic approach, and a commitment to the study of the world’s music’s aspects of human cultures.[19]Nettl, Bruno (1999). “The Institutionalization of Musicology: Perspectives of a North American Ethnomusicologist,” in ed(s) Nicholas Cook & Mark Everist, Rethinking Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 291.

Bruno Nettl’s explanation implies that ethnomusicology developed as a self-conscious element in musicology. It recognized that without being able to account for non-European musics, it could never claim universality, even at least as an aspiration. However from the mid-1870s onwards changes in Western cultural orientation were also accelerated by technological developments in the area of sound reproduction:

Development of instrument for measuring sound waves (1882).

Development of the carbon-button microphone (1876)

Development of the phonograph (1877)

Industrial development of tuning forks, by the likes of Karl Rudolph Koening (1890s)

Mass production of cylinder recordings begins (1902)

There were also significant political and cultural changes, including the Berlin Congress of 1885, where colonialism became a done deal— and, as celebration of this right to colonize, Africa was divided on a map amongst European imperial nations. From an academic point of view, there was the emergence of ethnology, philology, linguistics and anthropology as disciplines.

At the time, enthnology and anthropology begin to emerge as academic ways of rationalizing African cultural and social systems, two kinds of anthropology dominate the South African scene: One type is called social anthropology and the other volkekunde. Social anthropology drew on the British school of anthropology, whose inspiration had been the work of B K Malinowski. As it manifested in South Africa, social anthropology was specifically anti-political in the way that it simply refused to deal with the fact that the African societies it was studying were in fact bordered within the modern state of the Union of South Africa, choosing instead to view these societies as distinct tribal-states in themselves. Upon taking up appointment in social anthropology at the University of Cape Town from 1921, A Radcliffe-Brown’s contribution was hugely influential. In his theory of structural functionalism: practices in society fitted together to sustain stability, the function of a practice was just its role in holding up the social structure. Societies were viewed as defined tribal entities, and it was believed their stability was sustained by the tribal social formation and that social order was kept intact through the ‘social system’ and ‘kinship’ relations. What this anthropological gaze did was to keep the discourse on cultural matters and kinship ties, conveniently overlooking of national questions of politics, of land, of economy. In this sense early ethnographers mirrored the aspirations of the segregated state, which preferred theories that would hide away its own complicity.[20]Mamdani, Mahmood has argued that the South African state formation at that time could be better explained as a kind of despotic rule that happened to be decentralized, to the extent that each political identity carried with it a different set of assumptions of citizenship. Civic citizenship was racially defined. It spoke the language of rights, equality and civil law, and was the terrain of whites. There was also a limited citizenship, which was ethnically bound, of which African populations were deemed as its subjects. It spoke not of rights but of culture and customs. It too was enshrined in the power of the state. “When does a Settler become a Native? Reflections of the Colonial Roots of Citizenship in Equatorial and South Africa,” AC Jordan Professor Inaugural Lecture, 13th May 1998, University of Cape Town; and Mamdani, Mahmood (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. The intellectual blindspot of their own making was that tribal relations could not be seen as part-and-parcel of the state’s invention.

Thus early scholarship contributed to the increasing suspicion towards Africans who were urban self-styling in the cities, in its search for untampered or to use Tracey’s term, ‘unadulterated’ African tribal life.[21]Tracey, Hugh (1954). “The State of Folk Music in Bantu Africa,” International Folk Music Journal, 6, 32-36 Evidence from the 19th century, however, tells a different picture. In the middle of the 19th century, new worldviews against colonialism placed pressure on colonial governments to find alternative ways of administering power without direct force (but still capable of serving the colonial project). Theophilus Shepstone, the British colonial administrator, chose to resolve the challenge by finding African indigenous models of domination. In the legacy of Zulu king, Shaka kaSenzangakhona, he found a model of central control that circumvented some of the more liberal demands of British constitutional government.[22]Hamilton, Carolyn (1998). Terrific Majesty. Cambridge & London: Harvard U P, 76-78, 93. The strategies paid rigorous attention to detail, so that they would work and convince as colonial modes of governance. They were also imaginative and included the acting out of the role of Shaka in public ceremony, with Shepstone himself as Shaka. And conveying certain modes of public address, including heralding, izibongo (praise-poetry), that called the society to attention. During this moment tribality as a colonial mode of controlling African people was crafted and perfected.

But in the emerging ethnographies of the 1920s and 1930s, this historical reality was disregarded, and tribal ties were viewed as precolonial in their origin. The real political discourses which informed mobility, settlement patterns and economy of all people in South Africa did not feature, the emphasis was on custom, ritual and performance—the repertories by which Tracey’s African Dances became a possibility.

Volkekunde was a different ethnological tradition which grew side-by-side the development of social anthropology in the early to mid-20th century. It was inspired by German philology and the anthropology of Carl Meinhof. The emphasis was on language as a tool to study African cultures, but the languages were racially-structured, and language was seen to imply polity. It tended to be more governmental in its orientation and NJ van Warmelo, was a leading exponent of this tradition. He became government ethnologist from 1930. The Ethnological Section played a key role in setting up the terms for the determining of tribes out of the African population that existed in the Union of South Africa.[23]Pugach, Sara (2004). ‘Carl Meinhoff and the German Influence on Nicholas van Warmelo’s Ethnological and Linguistic Writing, 1927-1935.” Journal of Southern African Studies, 30/4, 825-845; also see Olwage, Grant (2002). “Scriptions of the Choral: the Historiography of Black South African Choralism,” SAMUS, 22, 29-45. In essence, they conducted bogus research studies which served as evidence for chieftaincy claims required for tribal demarcations. The historical evidence was recalled in such a way as to arrange/order African populations in a way effective for the state’s administration. The ordering of African populations as tribes also made them better governable as labour on the farms and mines. But more crucially as is the case with Tracey, the various traditions of ethnology grew side-by-side, and those who were embedded moved across different networks of publicity. Tracey worked for state broadcasting, at some point he worked for a commercial recording company and he interacted with the mining industry.

Tracey’s entry into field recording in the 1920s happened at the apex in the development of mechanical sound-reproduction technology, globally. Scholars providing earwitness to this time of transition, such as T W Adorno, were able to articulate the changes in communication inaugurated by the advent of sound technologies into an intellectual problem. Adorno once asked: “Does a symphony played on the air remain a symphony? Are the changes it undergoes by wireless transmission merely slight and negligible modifications or do these changes affect the very essence of the music?” Here Adorno argued that a symphony played on the sound reproduction technology of radio no longer remains a symphony, precisely because of the changes in the configuration, which miniaturizes the music. This makes it impossible for the listener to experience the full force of the symphony orchestra, thus engaging in a kind of atomized listening.[24]Adorno, T. W. (1945/1996). A social critique of radio music. The Kenyon Review, 18/3&4. This explained the abstractive element in the unmooring of sound from its locus of the human body; that is the ability of sound technologies to separate sound from its source.

The first recordings Tracey made were done on aluminium.[25]Muller, Carol Ann (1999). Rituals of Fertility and the Sacrifice of Desire: Nazarite Women’s Performance in South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 124. Aluminium records were made of uncoated aluminium and were used as a quick way of making one-off recordings in the mid-1920s. When technologies became available to coat the aluminium disks into permanent grooves in the 1930s, the simple mechanisms used by Tracey in the 1920s became less popular.[26]See Morton, D (2004). Sound Recording: The Life story of a Technology. London: Greenwood Press.

About the book

African Dances is a photographic book, with preliminary comments written by Tracey. The comments are about the various repertories of dance presented in the photographs. We are told that the photographs were taken by Merlyn Serven, whose expertise prior to the project was in the photography of Russian Ballet. Serven’s experience is noted as an important factor in the fulfilment of the project. We are told in the Acknowledgements section, that the author felt indebted to the Chamber of Mines, who gave him permission to pursue the study over the mines. The process of the study involved entering the compounds where African mine labourers lived. Once in the compound, Tracey and Serven would record and photograph the African performers.

Mr L G Hallett, who was the Chief Compound Manager at the Consolidated Main Reef Mines, was the one who would organize the groups of performers on behalf of Tracey. Tracey tells us that the photographs had to be taken on site on the mine property, but away from the modern industrial buildings that he felt were “incongruous” to the spirit of the project—which was to document the performances of the men in costume.[27]Tracey, Hugh (1952). African Dances of the Witwatersrand Gold Mines. Johannesburg: African Music Society, 2. For this objective Tracey required a backdrop that could suggest a possible tribal setting for the bodies on exhibition.

In charge of every compound was a compound manager. The recreational space which was part of the compound structure was positioned in such a way that it was hard to ignore any recreational activity happening within the compound, especially sound that emanated from there. In the early 1940s, loudspeakers were introduced as an addition to the African-aimed entertainment, that was already happening with the sports and leisure gatherings happening in the mines.[28]Mhlambi, Thokozani (2018). “African Orientations to Listening: The Case of Loudspeaker Broadcasting to Zulu-speaking Audiences in the 1940s.” Interference Journal, 6, 23-30. The mining industry was one of the major forces in the spread of African sport in Johannesburg in the 1930s and 1940s. But rather than promoting ‘urban’ sports such as soccer or rugby, the mining industry promoted activities that were seemingly more suitable to a rural-based labour force, hence the dance competitions between the different ‘tribes’. Miners themselves were governed by a vicious hierarchy, with ethnically-divided indunas (African supervisors) and a white compound manager as the ultimate authority.[29]Badenhorst, C & Mather, C, (1997). ‘Tribal Recreation and Recreating Tribalism: Culture, Leisure and Social Control on South Africa’s Gold Mines, 1940-1950,’ Journal of Southern African Studies, 23/3, 474-476.

The photographs give us a peek into what life was like in the compounds. They show us the arenas, where the men danced adorned in all kinds of imaginative costumes, which conveyed the traditional attire of each distinct group that was photographed. Some of the costumes were created by Hallet, who received special thanks in the book for having improvised many of the costumes worn by the men.[30]Tracey, African Dances, “Acknowledgments” Tracey considered the staged nature of the dances as a limitation in the appreciation of them—an experience he believed could only be seen in a village context: “It springs from the homely convictions of the village and not from the artifice of the stage, a limitation which, incidentally, makes it almost impossible to export an African dance outside its own domain.”[31]Tracey, African Dances, 2.

The dance competitions relied on the minerworkers being already organized into a hierarchy of ethnicity. This was usually based on language. Upon arriving in urban complexes like Johannesburg, migrants encountered men from other regions, (who probably also spoke languages they could not understand). As a result there was solidarity amongst those who spoke similar languages and came from the same regions. As Jeff Guy and Motlatsi Thabane (1988) have shown, through the study of Basotho mineworkers:

The vast majority of mineworkers have been drawn from clearly-defined regions in the rural areas, very often from amongst young men from the same district, or sharing the same cultural and linguistic background. Control, both in the compounds and at the work place, has often been facilitated by dividing mineworkers into discrete groups whose members appear to share similar geographical or social backgrounds—according to ‘tribe’—or if necessary dividing authority and privilege amongst members of different groups thereby diverting hostility from management towards other workers. Popular consciousness in Southern Africa is replete with ethnic judgements and generalisations on the essential nature of the Zulu, the Xhosa, the Basotho, the Mpondo, the Shangaans—statements which, although reflecting minimal social insight, do have considerable social weight. [32]“Technology, Ethnicity and Ideology: Basotho Miners and Shaft-Sinking on the South African Gold Mines,” Journal of Southern African Studies, 14/2, 258-259; see also Marks, Shula (1986). The Ambiguities of Dependence in South Africa: class, nationalism, and the state in twentieth-century Natal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

This solidarity was then used to structure the dance competitions as well. The fact that mine labourers were distinct tribal groups was used by the mining industry as a way of assuring whites that Africans were unlikely to insurrect. Assimilation to urban life was seen not as harmful, but also as a threat to the European presence. A mining publication wrote in 1944:

In the mining industry, however, the Natives are, almost without exception, tribalised, paying homage to their own chief, bowing to the authority of their tribal laws, and directly influenced by tribal custom.[33]“Introducing the Rand’s Native Mineworkers,” The SA Mining and Engineering Journal, 2 September 1944, 3-5.

The book was first published in Johannesburg, South Africa in the year 1952. The publisher was the African Music Society (AMS), the same organization that had undermined African composers such as Mohapeloa in their membership of the society. Tracey was a founding member of the AMS. The aim of the AMS was to highlight and promote the preservation of African folk musics.[34]See A: Minutes & Correspondence of African Music Society, 2nd February 1949. Manuscripts & Archives Department, University of Cape Town

Ingoma

In order to understand the genesis of the dance competitions in South African urban social life, I would like to give an example of a public incident in Durban related to the establishment of dance arenas, which were similar to those in the Johannesburg mines. Cloonan & Johnson (2002) have suggested that “part of the clamour of modernity is a public sonic brawling, as urban space becomes a site of acoustic conflict.”[35]Cited in Birdsall, Nazi Soundscapes, 36. Acoustic clashes appeared in a number of ways in the urban space of the industrial city of Durban in the 1920s and 1930s.

In June 1929, labourers, most of whom were under the Industrial and Commercial Worker’s Union (ICU), got into a noisy clash with police and white vigilante at the ICU Worker’s Hall in Durban. They were chanting well known ingoma songs, emboldened with political themes of the times. The gathering of African multitudes in the city and the noise which they made must have drawn attention, as all ingoma-related dancing and the carrying of sticks within the city were banned following the incident.[36]Erlmann, African stars, 260. I use the term noise as it suggests sound in its unpleasant (even violent!) form. Ingoma represented a physical and sonic strategy of demanding attention. Indeed, there was a change in the way Africans were regulated in the city after that.

In the years following, in the 1930s, oppressive policies were ruthlessly interpreted, such as the Native Affairs Act of 1920 (and its hints of tribally based district councils) as well as the 1927 Native Administration Act. Popular political organization was severely hindered. Tribalization, cultural adaptationism were now the buzz words for the control of power. The passing of the Slums Act in 1934, the withdrawal of the Cape African Vote in 1936, and the Black (Native) Laws Amendment Act, which prevented the acquisition of land by Africans in urban areas except with the permission of the Governor-General, all accumulated in the intensification of the means of domination of African populations.

That day in 1929 must have left a chilling impression in the minds of Durban’s influential white population, because 10 years later, when Tracey proposed the establishment of an Ingoma dance arena to the city council, many did not like Tracey’s suggestion. The arena was to serve as a multipurpose centre, like what we may now call a ‘cultural village’, for preserving Zulu war dances and the “exhibition of native huts”. Dance competitions were to be held there. Controversy ensued when Mr T J Chester, the manager of the Durban Municipal Native Affairs Department, wrote a piece opposing the scheme in the Natal English newspaper, Daily News. Chester did not want natives living in the centre of the city as it was against municipal policy. Tracey answered, “although the exhibition of huts containing native crafts will be open seven days a week, no natives will live there, and the only time they will occupy the arena will be for a few hours a week when dancing is in progress.”[37]“Reply to Critics of the Native Dance Arena”, Daily News, 20th February 1939

Chester’s other concern was that Council had already given three playing fields elsewhere for natives to dance. Tracey contended “that these facilities will not encourage European interest and support of native dancing as much as would an arena in an area which is readily accessible to tourists, without going through a ‘black belt’.” Tracey went on to point out that the scheme would stimulate the market for native products. Furthermore, the scheme had already been supported by Mr H C Lugg, the Chief Native Commissioner for Natal, who felt that the scheme would be a “Godsend” to the native communities. Tracey believed that once Durban establishes the arena, other centres in the Union would follow suit.[38]“Reply to Critics of the Native Dance Arena”

“Zulu dances are as dead as the dodo!” an unnamed person (with the pseudonym Usingququ) retorted, “neither ricksha boys nor the native from the sugar estate would know anything about it.” The author went on to question the desirability of using Africans for the “purpose of stimulating the tourist traffic to this country, for the Zulu to be gazed upon by the tourist with eyes of curiosity mingled with pity”. He concludes “It is employment, not dancing, that the natives need.”[39]Daily News, 23rd March 1939

Usingququ’s letter touches on two vital undertones, firstly, by dismissing the authenticity of Zulu dancing, s/he exposes the implicit fabrication of these dances as traditional. The term ingoma (literally meaning ‘a song’)covers a diverse range of male song-dances, including isicathulo, isiBhaca, isishameni to mention a few. The use of the term captures the inseparability of dance from song within in some African performance contexts. Ingoma is not however a traditional form, it emerges through the convergence of disparate regional forms in Durban during the First World War.[40]Erlmann African Stars, 259. Secondly, by insisting that these dances are dead s/he assaults the attempt to tribalize Africans that was rising at the time.

A response to Usingqunqu’s letter appeared a few weeks later. The author of the response asserted that although the dancing would not give the natives employment “it would nevertheless be helping substantially to give them that recreation essential to produce the sound mind and sound body”. “The Zulu war dance was a psychological dance with an object, and through a prolonged period of peace it has naturally gone out of fashion, just as the minuet has gone out of fashion in European dancing.”((Daily News, [month uknown] 1939))

The minuet, a 17th century European courtly dance with elegant steps. Ingoma, a hybrid war dance involving sticks and flaming gestures of traditional regiment. One can assume in the comparison that the Zulu war dance and the minuet are each the highest calibre of dancing in the cultures they belong to. If the war dance is the only dance capable of being redeemed, against an order of knowledge where the minuet is concerned, then the need to salvage the African is of more significance. Showcasing a tamed version of the war dance may stand as evidence of the progress colonialism has made in bringing discipline and order to natives.

See this in your mind taking place during a time of war! The war dance taking place within an arena, with gazing European eyes, against the prevailing Second World War became a form of escape that naturalized the African within the European world simply as ‘entertainment’. Implied in the response is that improving the black person is by far the most important gift whites can give the Africans. It matters that the form under discussion is dance, an artistic expression which places the body at the centre. The body carries the burden of visibility, it must be seen. It marked a move in the co-opting of ingoma and its practitioners into the city fabric, and firmly naturalized ingoma within the public life of the port city. The gutsy timbre, which could only be manifest through multiple voices chorusing, unlegislated, was now lost. Even the physicality of the dance itself, the sounds of stamping feet, the cheers of multitudes drowning out the cityscape—all of which add to the aural environment—were now gone.

Resuming Work on the Mines

Leaving Durban, Tracey went on to resume his work on the mines in Johannesburg. By this time in the mid-1940s, protest action in the mines was on the increase. As protest action intensified, the mine industry decided to promote the formation of dance clubs as a form of leisure. These dance clubs were arranged according to the structural hierarchies of tribes that were already existing in the mines. Through the Association of Mine Managers, ‘tribal dancing’ became a universal phenomenon in the Witwatersrand area. This led to a wide-scale erection of dance arenas. Similar incidents as those which happened to ingoma in Durban, were reported in Johannesburg. In 1944, competition organizers felt that the choreography of the Chopi performers was becoming too aggressive. The Chopi men were then asked to replace the movements with gentler, less threatening gestures, which were suitable for tourist exhibition.[41] Badenhorst, C & Mather, C, (1997). ‘Tribal Recreation and Recreating Tribalism: Culture, Leisure and Social Control on South Africa’s Gold Mines, 1940-1950,’ Journal of Southern African Studies, 23/3, 478.

In Johannesburg, Tracey again became involved in efforts to create dance arenas. The arena at the Consolidated Main Reef Mine was the first one to be built according to his specifications in 1943. This is where most of the images represented in the book were taken. Tracey’s arena could accommodate three thousand spectators.[42]Felber, Garret (2010). “Tracing Tribe: Hugh Tracey and the Cultural Politics of Retribalisation,” SAMUS, 30/31, 36. Its shape was a semi-circle structure with an open area at its focal point, and audience seating around it. To promote attendance at the events, the Mines provided transport and gave the spectators carnival objects like whistles, rattles, etc. in order to the cheer the performers along. There were many whites who attended the events as well.

The emphasis was not only on the dancefloor itself, but also in the comfortability of the viewing experience. With this arrangement, Tracey believed that “the art of native dancing should receive its proper recognition from white and black alike”.[43] Tracey, African Dances, “Acknowledgements” Tracey felt the need to quell the fears of insurrection by declaring to his readers that the dances were not war dances, but rather “secular dances”.[44] Tracey, African Dances, 1. Tracey’s need to explain was unsurprising given the newspaper debate on ingoma, that he was involved in while he was based in Durban a few years before.

The attendance of mineworkers would have been hampered by the shift-work system that was used in the mines, which meant that a certain section of the mine labourers would be available at a particular time, for rehearsals and actual competitions. African women were not permitted to do mine work. This meant that African men would leave their homes faraway and come to work on the mines on their own. They would be surrounded by men all the time, except if they slipped away into the slums where Africans, poor whites and Chinese lived side-by-side. There mineworkers could find some of that strong concoction liquor that was not permitted by government. This is the site where they were likely to come across women dancing in the city.

Now from the inventory of information I have retrieved from examining the book, it is easy to conclude that that part of our history was racial in how it structured social relations. I do not need to pinpoint the aspects that suggest racism, as I think that the fact is now accepted as true. Indeed we can also conclude that the way African realities were studied and made into history tended to echo the racist views purported by the state, albeit under different terms. Especially as I have highlighted that Tracey was such an enthusiast of African music. Indeed, during his time he would have been considered as one of the more well-meaning whites by the African educated class and others who interacted with him. Furthermore, unlike previous scholars such as Hornbostel, Tracey actually lived in Africa; he learnt to speak African languages and used his social skills to collect background information on the repertories he recorded.[45]See Nketia, “African Music and Western Praxis,” 39.

I am also aware of myself as a brown-skinned African person, whose first language is Zulu, as being beyond the scope of who was imagined as the main audience for the text. And so there is discomfort caused by the tone of address in the book, whose amplifier stands facing European ears. It seems to be suggesting that perhaps I belong elsewhere in its distribution of power relations, that perhaps my position is better fitted standing with the mine dancers, who come alive through the pages as unknown subjects, who are then forced into being objects, by the process of objectivation instituted through the camera and the written-word. We should have Susan Sontag in mind in this instance, who suggests that a photograph should be taken as a way of seeing the events that unfolded, and not seeing itself. It allows us access to that reality, for which we do not have direct experience.[46]Sontag, Susan, 2007. At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches. London: Penguin Books, 124-125. It is through the labour of photography that the mine men are actualized as a part of the cultural object of the book and therefore become activated into that world—no longer as subjects of their own making, but as part and parcel of the process (or way of seeing events), the given set of conditions by which the book becomes a possibility.

Indications on who the intended audience was are evident from the opening pages. The ‘Foreword’ begins with the proclamation: “for many decades Westerners have been at work to civilise the Bantu”—a clear designation of authority to civilise, and at the same time a designation of readership in terms of the book itself. The imagined audience of the book is also shown in the inclusion of a glossary of terms, the fact that words need to be explained which would not necessarily need explaining to a first language Zulu speaker, for example. Most of the terms fit well into the Tekela-Zunda cluster of languages, as classified by linguists, which are mutually intelligible. These cover the majority of the languages spoken in southern Africa; and would therefore not need explaining to most of this population.

The ‘Brief Glossary,’ gives short explanations of some of the terms used by the mine dancers. This section gives a good indication of the repertoire of ideas about dance and performance, which Tracey might have viewed as important based on his observations of the dances in the mines. In a sense the repertoire of ideas represented in the glossary also gives us an indication of what he may have perceived as a hidden world for his English readers; which he felt ought to be understood in order to grasp the contents of the book.

Opening Up the Future

The challenge in early studies of African music, is that those who defined it had to explain it in terms of and against the aesthetic values of European music. It is not to say that they themselves were not aware of this; no, in fact in their attempt to overcome this weakness they were constantly inventing theories which they believed would give them an analytical approach to dealing with their bias.

Well that was their challenge. Our challenge today: is how do we receive their contributions in African music scholarship? One of the ways in which this bias emanated was in how the authors re-directed their own ignorance on African languages and culture on to their readers, who were presumed to be equally ignorant. Ethnomusicologist, Bruno Nettl (1975), hints precisely at this problem when he says, “one is perhaps unable to absorb new information about a new musical culture except by making implicit comparison to something already known.”[47]“Comparison and Comparative Method in Ethnomusicology.” Yearbook for InterAmerican Musical Research, 9, 148-161. This something that is “already known” is the presumption I am talking about. It presents not only a methodological but ontological crisis for African people who are on the quest for self-knowledge, who may find themselves unaccommodated in the mode of address (and by implication its substance) at work in the literature.

Africanist scholar V Y Mudimbe (1988) writes, “The main problem concerning the being of African discourse remains one of transference of methods and their cultural integration in Africa.”[48]Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa, 183. My sense is that a critical reading of African Dances, as I have done here, may not be useful for us in terms of opening up the future,[49]I have Frantz Fanon in mind here who writes, “When the colonized intellectual writing for his people uses the past he must do so with the intention of opening up the future, of spurring them into action and fostering hope. But in order to secure hope, in order to give it substance, he must take part in the action and commit himself body and soul to the national struggle.”[1] Fanon, Frantz (1961). Wretched of the Earth, 167. even though it unveils the injustice of a particular moment (and its replicable factors).

The challenges that eventuated into the field of practice known as ethnomusicology/African music scholarship were circumscribed: in the kinds of questions it asked, the limits of its investigation and the way it chose to arrange African repertories of sound—sometimes they were organized as dance, as Tracey has done in this book. At other times the organization was focused on the classification of musical instruments, like Percival Kirby does.[50] Kirby, Percival R (1934). The Musical Instruments of the Native Races of South Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand U P. But by these taxonomies imposed on African phenomena, a whole new discourse emerges—which cannot be properly called ‘traditional’. It is a discourse whose coding is in the excessive organizing of facts, symbols and objects, such that they become unimaginable outside those technologies that make them visible/audible. In this case, the photography of Serven, foregrounded by the archive collection of sounds of Tracey, which we are then prompted to imagine through the compilation in the book.

| 1. | ↑ | See Mudimbe, VY (1991). The Invention of Africa. Indiana: Bloomington Press; Agawu, Victor Kofi (2003). Representing African Music. New York: Routledge. |

| 2. | ↑ | International Library of African Music (refer to discussion further on). |

| 3. | ↑ | Cowley, John (1994). “Recordings in London of African and West Indian Music in the 1920s and 1930s,” Musical Traditions. 12, 13-26. |

| 4. | ↑ | Hornbostel, Erich M von (1928). “African Negro Music,” Africa. 1:60. |

| 5. | ↑ | See Allen, Lara (2007). “Preserving a Nation’s Heritage: The Gallo Music Archive and South African Popular Music,” Fontes Artis Musicae. 54/3, 263-279. |

| 6. | ↑ | Hamilton, Carolyn & Leibhammer, Nessa (2016). “Introduction,” Tribing and Untribing. Pietermaritzburg: UKZN Press, 13-15. |

| 7. | ↑ | ‘The New African Movement,’ Accessed 18th June 2018 |

| 11. | ↑ | “SABC Bantu Broadcasts”, Umlindi 4th August 1945. |

| 9. | ↑ | Erlmann, Veit (1991). African stars: Studies in black South African performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 123. |

| 10. | ↑ | See Lucia, Christine (2011). “Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa and the Heritage of African Song,” African Music. 9/1, 56-86. |

| 12. | ↑ | Mohapeloa, J P (1951). ‘Preface’ in Khalima-Nosi tsa ‘Mino Oa Kajeno : Harnessing Salient Features of Modern African Music. Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot. |

| 13. | ↑ | See “A: Minutes & Correspondence of African Music Society,” 2nd February 1949, P R Kirby Collection, BC750/A, Manuscripts & Archives Department, University of Cape Town; “List of Members,” 30th April 1948, P R Kirby Collection, BC750/A, Manuscripts & Archives Department, University of Cape Town. |

| 14. | ↑ | See Lucia, Christine (2011). “Joshua Pulumo Mohapeloa and the Heritage of African Song,” African Music. 9/1, 67-80. |

| 15. | ↑ | International Library of African Music’s Hugh Tracey correspondence files, cited in Coetzee, Paulette (2014). Performing Whiteness: Representing Otherness: Hugh Tracey and African Music. Phd thesis, Rhodes University, 83-88. |

| 16. | ↑ | See ‘Chapter 10’ in Mhlambi, Thokozani N (2015). Early Radio Broadcasting in South Africa: Culture, Modernity & Technology (Doctoral Thesis). University of Cape Town, Cape Town. |

| 17. | ↑ | Nketia, J H Kwabena (1986). “African Music and Western Praxis: A Review of Western Perspectives on African Musicology,” Canadian Journal of African Studies, 20/1, 39; Tracey, “The State of Folk Music in Bantu Africa,” 5. |

| 18. | ↑ | See Amoros, Luis Gimenez (2018). Tracing the Mbira Sound Archive in Zimbabwe. New York: Routledge, 1-3. |

| 19. | ↑ | Nettl, Bruno (1999). “The Institutionalization of Musicology: Perspectives of a North American Ethnomusicologist,” in ed(s) Nicholas Cook & Mark Everist, Rethinking Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 291. |

| 20. | ↑ | Mamdani, Mahmood has argued that the South African state formation at that time could be better explained as a kind of despotic rule that happened to be decentralized, to the extent that each political identity carried with it a different set of assumptions of citizenship. Civic citizenship was racially defined. It spoke the language of rights, equality and civil law, and was the terrain of whites. There was also a limited citizenship, which was ethnically bound, of which African populations were deemed as its subjects. It spoke not of rights but of culture and customs. It too was enshrined in the power of the state. “When does a Settler become a Native? Reflections of the Colonial Roots of Citizenship in Equatorial and South Africa,” AC Jordan Professor Inaugural Lecture, 13th May 1998, University of Cape Town; and Mamdani, Mahmood (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. |

| 21. | ↑ | Tracey, Hugh (1954). “The State of Folk Music in Bantu Africa,” International Folk Music Journal, 6, 32-36 |

| 22. | ↑ | Hamilton, Carolyn (1998). Terrific Majesty. Cambridge & London: Harvard U P, 76-78, 93. |

| 23. | ↑ | Pugach, Sara (2004). ‘Carl Meinhoff and the German Influence on Nicholas van Warmelo’s Ethnological and Linguistic Writing, 1927-1935.” Journal of Southern African Studies, 30/4, 825-845; also see Olwage, Grant (2002). “Scriptions of the Choral: the Historiography of Black South African Choralism,” SAMUS, 22, 29-45. |

| 24. | ↑ | Adorno, T. W. (1945/1996). A social critique of radio music. The Kenyon Review, 18/3&4. |

| 25. | ↑ | Muller, Carol Ann (1999). Rituals of Fertility and the Sacrifice of Desire: Nazarite Women’s Performance in South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 124. |

| 26. | ↑ | See Morton, D (2004). Sound Recording: The Life story of a Technology. London: Greenwood Press. |

| 27. | ↑ | Tracey, Hugh (1952). African Dances of the Witwatersrand Gold Mines. Johannesburg: African Music Society, 2. |

| 28. | ↑ | Mhlambi, Thokozani (2018). “African Orientations to Listening: The Case of Loudspeaker Broadcasting to Zulu-speaking Audiences in the 1940s.” Interference Journal, 6, 23-30. |

| 29. | ↑ | Badenhorst, C & Mather, C, (1997). ‘Tribal Recreation and Recreating Tribalism: Culture, Leisure and Social Control on South Africa’s Gold Mines, 1940-1950,’ Journal of Southern African Studies, 23/3, 474-476. |

| 30. | ↑ | Tracey, African Dances, “Acknowledgments” |

| 31. | ↑ | Tracey, African Dances, 2. |

| 32. | ↑ | “Technology, Ethnicity and Ideology: Basotho Miners and Shaft-Sinking on the South African Gold Mines,” Journal of Southern African Studies, 14/2, 258-259; see also Marks, Shula (1986). The Ambiguities of Dependence in South Africa: class, nationalism, and the state in twentieth-century Natal. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. |

| 33. | ↑ | “Introducing the Rand’s Native Mineworkers,” The SA Mining and Engineering Journal, 2 September 1944, 3-5. |

| 34. | ↑ | See A: Minutes & Correspondence of African Music Society, 2nd February 1949. Manuscripts & Archives Department, University of Cape Town |

| 35. | ↑ | Cited in Birdsall, Nazi Soundscapes, 36. |

| 36. | ↑ | Erlmann, African stars, 260. |

| 37. | ↑ | “Reply to Critics of the Native Dance Arena”, Daily News, 20th February 1939 |

| 38. | ↑ | “Reply to Critics of the Native Dance Arena” |

| 39. | ↑ | Daily News, 23rd March 1939 |

| 40. | ↑ | Erlmann African Stars, 259. |

| 41. | ↑ | Badenhorst, C & Mather, C, (1997). ‘Tribal Recreation and Recreating Tribalism: Culture, Leisure and Social Control on South Africa’s Gold Mines, 1940-1950,’ Journal of Southern African Studies, 23/3, 478. |

| 42. | ↑ | Felber, Garret (2010). “Tracing Tribe: Hugh Tracey and the Cultural Politics of Retribalisation,” SAMUS, 30/31, 36. |

| 43. | ↑ | Tracey, African Dances, “Acknowledgements” |

| 44. | ↑ | Tracey, African Dances, 1. |

| 45. | ↑ | See Nketia, “African Music and Western Praxis,” 39. |

| 46. | ↑ | Sontag, Susan, 2007. At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches. London: Penguin Books, 124-125. |

| 47. | ↑ | “Comparison and Comparative Method in Ethnomusicology.” Yearbook for InterAmerican Musical Research, 9, 148-161. |

| 48. | ↑ | Mudimbe, The Invention of Africa, 183. |

| 49. | ↑ | I have Frantz Fanon in mind here who writes, “When the colonized intellectual writing for his people uses the past he must do so with the intention of opening up the future, of spurring them into action and fostering hope. But in order to secure hope, in order to give it substance, he must take part in the action and commit himself body and soul to the national struggle.”[1] Fanon, Frantz (1961). Wretched of the Earth, 167. |

| 50. | ↑ | Kirby, Percival R (1934). The Musical Instruments of the Native Races of South Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand U P. |