STEPHANUS MULLER

Afrikosmos: the keyboard as a Turing machine

On 24 September 2022, or what is known as Heritage Day in South Africa, NewMusicSA honoured its founding President,[1]For background to Blake’s role in establishing NewMusicSA, see Stephanus Muller, ‘Miniature blueprints, spider stratagems: a Michael Blake retrospective at 60, Musical Times 152:1917 (Winter 2011), pp. 71-92, esp. pp. 80-82. Michael Blake, by hosting a performance of selected pieces from his Afrikosmos, published in 2022 by Bardic Edition in six volumes (BDE 1281; BDE 1282; BDE 1283; BDE 1284; BDE 1285). Written for solo piano, the contents of Afrikosmos are described on each of the six title pages as ‘75 Progressive Piano Pieces’, and are consecutively numbered from 1 to 75 throughout the six volumes.[2]There are 15 pieces in Volume 1, 14 pieces in Volume 2, 13 pieces in Volume 3, 12 pieces in Volume 4, 11 pieces in Volume 5 and 10 pieces in Volume 6.

Each of the volumes has an identical introduction, in which the composer explains (a) the connection between Afrikosmos and Béla Bartók’s Mikrokosmos (which consists of 153 progressive piano pieces in six volumes, composed between 1926 and 1939), (b) provides brief historical context for the work as a whole, and (c) explains his compositional and aesthetic approach to the set of six volumes. Following the introduction, each volume also contains a Contents section in which brief and informative notes on each individual piece are provided.

Regarding the titular reference to Bartók’s famous set of didactic pieces, which have become a classic of twentieth-century piano repertoire, Blake singles out ‘the importance he [Bartók] assigns to contrapuntal music, and on the other hand the influence of folk music from Eastern Europe.’ He continues:

I chose not to replicate the kind of technical exercises Bartók included for didactic purposes. However, I did follow his method of starting with the simplest pieces and working towards the more advanced pieces in the final volume. And I did explore in as comprehensive a way as possible the vast range of traditional music from sub-Saharan Africa.

As I have written elsewhere, historically Bartók has been a significant point of reference for composers of African art music,[3]See Stephanus Muller, ‘Michael Blake’s String Quartets and the Idea of African Art Music’, Tempo 76:300 (2022), pp. 6-17, esp. pp. 15-16. and in this collection of piano pieces, Blake acknowledges this inspirational debt more unambiguously than in any of his other works. The clear intertextual reference, introductory remarks, and descriptive notes[4]Bartók is referenced specifically in: ‘Canon at the Octave [Trad. Arr. Blake]’ (no. 16, volume 2); ‘Latshon’ilanga (The sun has set)’ (no. 27, volume 2); ‘Postcards from South Africa’ (no. 41, volume 3); ‘Emerging Melody’ (no. 46, volume 4); ‘The Seven Steps’ (no. 55, volume 5); ‘Night Music’ (no. 68, volume 6); ‘Diary of a Dung Beetle’ (no. 71, volume 6) and ‘Dance in Seakhi Rhythm (Homage to Bartók and JP Mohapeloa)’ (no. 75, volume 6). also frame questions about the appropriation of African musical materials very deliberately: historically (by using/employing Bartók’s modernist precedent of turning to folk music as source of material) and compositionally (by experimenting with and utilizing modes/scales, variation techniques, arrangement, and genres associated with African traditional music following Bartók’s engagement with Hungarian folk music).

In an academic seminar at the Africa Open Institute during which Blake discussed Afrikosmos,[5] Seminar notes, 29 September 2022, Africa Open Institute, Stellenbosch University. the composer reiterated that he tried to explore the music of Sub-Saharan Africa in as comprehensive a way as possible, but added that he also used cut-ups of material from favorite European pieces and composers like Robert Schumann.[6]Examples are ‘Scents of Childhood 2 – Homage to Schumann’ (no. 59, volume 5), pp. 16-19); and ‘Scents of Childhood 3 – Homage to Schumann and Puccini’, (no. 70, volume 6), pp. 29-31. Sometimes a short, single phrase could generate an entire piece.

The introduction also provides historical context relating to the origin and development of the set of piano pieces. Blake explains that the ‘idea of writing an African response to Bartók’s Mikrokosmos has a long genesis’, the starting point of which he locates in a commission he received from pianist Thalia Myers in 2003 on behalf of the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM). Myers was the compiler and editor of Spectrum Volume 4, an international collection of 66 miniatures for solo piano, and Blake responded to the commission by writing iKos’tina.[7]The piece, dedicated to Thalia Myers, is included as no. 34 in Volume 3 of Afrikosmos (p. 13), and described as follows in the Contents notes: ‘Translated as “concertina” in isiXhosa it is one of the many instruments imported and adapted for local use, often played by rural musicians who may be walking along the roadside, or played in bands together with guitars and other instruments’. He only returned to the idea in June 2015, when he took up a residency at the Rockefeller Writers Centre in Bellagio, Italy. During this residency he conceptualized the project, taking another five years to finish it. Although each piece is precisely dated and the place of composition documented at its conclusion, chronology plays no role in the organization of the six volumes (as has been explained above, the pieces are organized according to the degree of difficulty the writing poses to the prospective pianist, with volume six containing the most complex pieces).

Lastly, the introduction provides instructive pointers with respect to the compositional approach of the composer:

Each volume roughly follows a similar format, with one or two pieces that fall into each of the following genres: studies, pieces focusing on rhythm and texture, character pieces, dances, pieces exploring a mode or scale, folksong arrangements and variations, transcriptions and homages […]

While a few pieces are piano transcriptions of existing music, most pieces are either written in a neo-African style, or reflect my own aesthetic which has drawn on African musical material and aesthetics since the mid-1970s. These include:

The anhemitonic pentatonic scale: a five-note scale which has no semitones, for example D-E-G-A-B;

Xhosa bow harmony: two triads which are built on the two fundamental pitches of an uhadi bow, for example C-E-G and D-F sharp-A;

Bow scale: the hexatonic scale resulting from the two bow chords above: C-D-E-F sharp-G-A (not the whole-tone hexatonic scale, used by Debussy for example);

Interlocking: different rhythmic parts alternating to create a single line, which can give an impression of great speed;

Polyrhythm: simultaneously combining contrasting rhythms.

The African compositional material listed here, can be illustrated by a few examples. The very first piece, ‘To Comfort a Child (Lullaby)’ (no. 1, volume 1), demonstrates the use of the anhemitonic pentatonic scale, in a simple arrangement of a traditional Xhosa song:

Example 1:

An example of non-triadic bow harmony can be seen in the parallel perfect fourths that alternate between D-G and C-F in the accompaniment to a ‘traditional Xhosa bow song’ (description by the composer), presumably notated by Xhosa music scholar Dave Dargie (whose translation of the text inspired the title):

Example 2:

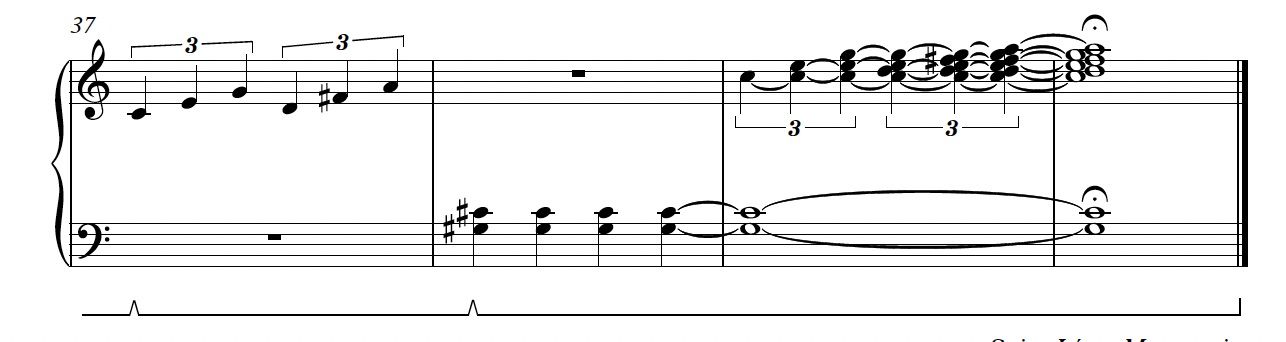

The last four bars of ‘Two modes interlocking’ (no. 38, volume 3), show the hexatonic Xhosa Bow scale on C in the right hand (bar 37), stacking up through sustained notes into the chords based on this scale (bars 38-39:

Example 3:

In a piece dedicated to his friend, Ugandan composer Justinian Tamusuza, Blake applies simple interlocking between the hands:

Example 4:

The right-hand quadruplets in ‘Heaven’s Bow’ (no. 67, volume 6), played against a regular division of the the 3/8 time signature, and becoming (in bar 35) a thinned out version of this pattern, provides a subtle and sustained basis for polyrhythmic texture throughout the piece:

Example 5:

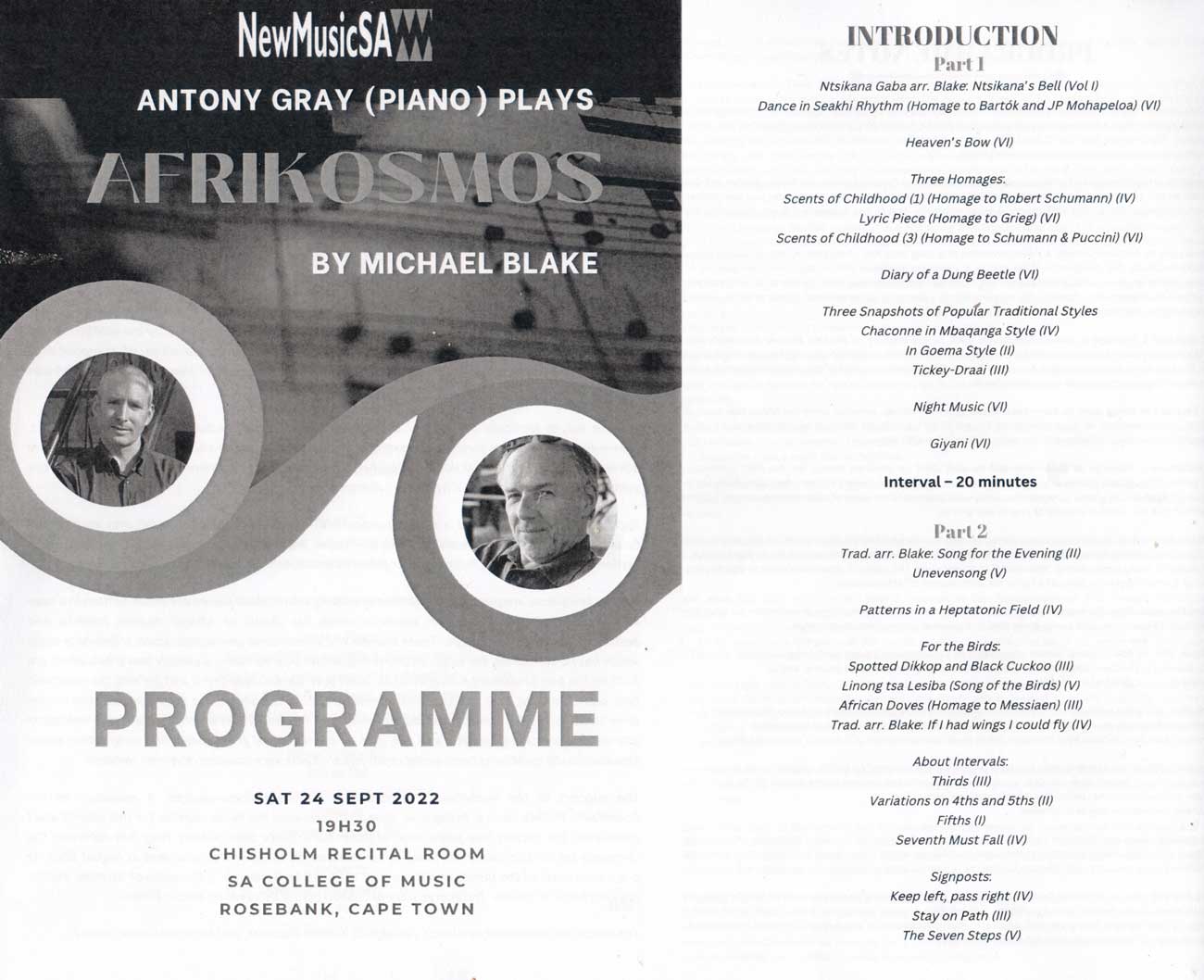

Tony Gray’s performance on 24 September 2022 in the Chisholm Recital Room at the South African College of Music, University of Cape Town, was arranged in two parts, with pieces selected and grouped together to create a balanced concert event, rather than a systematic exploration of the six volumes. Gray knows the music intimately, having premiered most of the pieces in a three-part soirée in Le Genesteix in the salon of Stephen Pettitt,[8] Programme notes, NewMusicSA Afrikosmos Concert, 24 September 2022. and having recorded the complete Afrikosmos for the Divine Art label. This settled knowledge of the work contributed much to the sense that the programme provided a perspective on a truly interesting and even remarkable project. As there was no provisional quality to the playing, a getting-to-grips with the music, one was allowed, in a sense, to think about Blake’s Afrikosmos as a new thing in the world, rather than a proposition to be considered.

Gray’s consummate pianism allowed the music to sound, the chords to carry, the single tones and overtones to linger. In the brittle, nervous, repetitive passages he didn’t rush, and didn’t do too much, allowing the music to be. Infusing the programme in its entirety, in composition and performance, was an ever-present appreciation of sound, quietness, dying sounds, the length of sound as it dies. This music breathes a twentieth-century American experimental sensibility in its motionlessness, sounding introspection, the deliberate affordance of allowing sonority to be sounded again and again until its constituent colours start separating under the operation of repetition.

The programme featured pieces that overwhelmingly favour the middle registers of the piano, with only rare excursions to the outer extremities. It was a selection that showed how the composer employs the piano as a stenography machine of musical ideas, an instrument in the Kittlerian sense, situating it in (South) Africa in a markedly different, contrasting, way to its nineteenth-century development that remains the governing aesthetic for piano writing (and performance) in South Africa. The piano in Afrikosmos (admirably complemented by Gray’s pianism) is not reduced, as it were, but presented as a different kind of instrument that facilitates the intimate aura of the child’s musical exploration in the language of the mature composer. Perhaps less so than in any of Blake’s other pieces – especially the piano pieces – the Afrikosmos isn’t explorative of the technical potential of the instrument, and this includes the exploration of the instrument’s colouristic possibilities. Pedaling is sometimes called for, but the full sonorities of the released strings are not often required for this music (Gray’s performance honoured this by his application of only very light dashes of the damper pedal, except when required to extend sound durations in very specific contexts, and no use at all of the una corda), and extended piano techniques mostly absent.[9] There are exeptions, like ‘Sefapanosaurus’ (no. 4, volume 1), which is a graphic score and requires the pianist to wear woollen gloves. The default mode is also not a highly percussive one, but rather what one would describe as airy, or aerated. What this means, compositionally, is the use of repeated notes, legato writing often confined to melodic fragments, open fifths and octave intervals in parallel movement that provide a lighter, transparent sonority compared to tertian-based chords, misalignment of contrapuntal lines that prevents the counterpoint from closing down in lock-step, instead allowing it to skip forward in light and loose allegiances, fragments of figures or gestures that follow without careful seam stitching, endings that disappear off the page in nothingness, as in the ending of ‘Tickey-draai’ below:

Example 6:

The performance showed these compositional elements to their best advantage through the tempi chosen by Gray, allowing silences to play a meaningful role in the music, and by restricting the use of tempo rubato to achieve phrasing and the shaping of lines. The latter is a particularly important and felicitous contribution the pianist made to Blake’s Afrikosmos (not only in the live performance in Cape Town, but also in the Divine Art recording), as it prevents the music from tilting into narcissist contemplation when material is radically pared down, or from sliding into sentimental murmurings of melodic sweet-nothings.

It has been one of Blake’s great talents as a composer to find and employ performers who are aesthetically and temperamentally receptive to his ideas, and to have his music performed by them.

One of the interesting (and beautiful) contributions of this writing for the piano is its redirection of focus to the figure of what might have been accompaniment. In his Cape Town performance, Gray continually allowed soprano melodies to sing well above soft harmonic carpeting, but in ‘Heaven’s Bow’ (no. 67, volume 6), for example, or in ‘Night Music’ (no. 68, volume 6), the repeated accompaniment-like material was also foregrounded – compositionally as in performance – as its own thing, demanding of attention.[10] Blake is aware of this play on aural perspective, as is evident from his note on ‘Latshon’ilanga (The sun has set) (no. 26, volume 2), where he connects it with a Bartókian device of assigning the melody to the left hand and the accompaniment to the right hand. See also ‘Variations on a Flute Tune (no. 39, volume 3). In the two examples cited above, however, the very boundaries between melody and accompaniment are eroded, rather than registerally displaced.

Example 7:

This bringing forward of the background, and the careful rendering of the background-foreground has the magical effect of evoking, through their absence, the memory of melodies we had once heard, or think we had heard; memories recalled not by their sounding, but by their context of embedment. This music is replete with gaps and openings, left as weathered stonework in vast imaginaries of great beauty and sadness, where the singing is nourished by the sounds of men and women who lived long ago.

Example 8:

And yet, despite the way the previous sentence was prompted by an affective response to Gray’s performance of the programme in Cape Town, Blake’s Afrikosmos doesn’t strike me as ‘spiritual’ music; nor did Gray’s performance convince me otherwise. Returning to the idea of the piano as an apparatus, hearing the programme on 24 September made me think of the keyboard as a Turing machine that implements algorithms of beauty, referencing aspects of form, surface considerations of contrapuntally coded provisional harmony and disharmony, considerations of time and colour, crystalline silences. Of course, this leads one to interrogate what ‘spirituality’ might mean, and back to the (hardly original) question that asks if beauty, for example in the way it manifests in ‘Variations on 4ths and 5ths’ (no. 23, volume 2) is not the ultimate, and only, spiritual attainment.

Example 9:

On the other hand, sounds that are so sculpturally aware of themselves as sounds, constitute a material take on music and musical material that seems to me profoundly indifferent to history and soul. In this sense, this is a completely hedonistic art, in the best possible taste. But an art, nevertheless, that doesn’t profess a single article of faith not governed by taste’s ordering sensibility.

At the AOI seminar on 29 September, Blake was asked about Christopher Alexander’s architectural vision of deep connectivity, articulated in his fifteen fundamental properties for deep connectivity in The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe.[11]Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe, Book One, ‘The Phenomenon of Life’ (Berkeley, California: The Center for Environmental Structure), 2002, esp. Chapter Five, entitled Fifteen Fundamental Properties, pp. 143-242. Blake had long had the book in his possession (since 2010, when he encountered it for the first time). Most of Alexander’s properties provide highly stimulating points of departure for a consideration of Blake’s music in general, and Afrikosmos in particular. This is not to say that he in any way worked according to a systematic, theoretical application of these ideas (which he didn’t), but only that these properties are all-encompassing enough to structure aesthetic contemplation across media and styles, that the composer himself finds these ideas productive in thinking about his work and that living with the book, and non-systematically engaging with its ideas, may have amplified aesthetic predilections or encouraged latent assumptions in the creative imagination.

Some of these properties have found their way into the language of this review already, even if slightly differently formulated: ‘alternating repetition’, ‘gradients’, ‘echoes’, ‘the void’, ‘simplicity and inner calm’, ‘deep interlock and ambiguity’, and ‘good shape’. Others easily could have, but didn’t: ‘levels of scale’, strong centers’, ‘positive space’, ‘local symmetries’, ‘contrast’, ‘roughness’, and ‘non-separateness’.

The property that received most discussion at the AOI seminar was the one of ‘boundaries’. The most obvious of which, in the case of Blake’s music in general, and Afrikosmos in particular, is notation: the externalization of the control that lies in the notion, and finely honed intuition, that we call ‘taste’. Already in this realization, is the acknowledgement of an outer boundary, and an inner one, and the boundaries infinitely suggested by bounded, discrete sonic structures realized in notation and refined by taste. The purpose of the boundary, in Alexander’s words, is two-fold:

First, it focuses attention on the center and thus helps to produce the center. It does this by forming the field of force which creates and intensifies the center which is bounded. Second, it unites the center which is being bounded with the world beyond the boundary.[12]Ibid., pp. 158-59.

The constituted center of Afrikosmos and its force field, and its historical and aesthetic boundary connection to Microkosmos with its constituted center and force field, South and North, and the boundaries within boundaries of both these bounded texts to the exponentially multiplying boundaries of the worlds – aesthetic and non-aesthetic – beyond these musical visions: all of these considerations are, through inclusion or omission, relevant to this set of piano pieces.

Invoking, then, Germaine de Stael’s view that taste is to literature (or music, in this case) what propriety is to society, Afrikosmos, as an inscription of taste, is a monument to the questions raised by white South African culture and art, and the role in this culture of taste in the production of bounded centres.

Music examples and cover designs used by permission of Bardic Edition, Music Publishers.

Afrikosmos will be released as a 3CD set in 2023 by Divine Art Recordings Group.

| 1. | ↑ | For background to Blake’s role in establishing NewMusicSA, see Stephanus Muller, ‘Miniature blueprints, spider stratagems: a Michael Blake retrospective at 60, Musical Times 152:1917 (Winter 2011), pp. 71-92, esp. pp. 80-82. |

| 2. | ↑ | There are 15 pieces in Volume 1, 14 pieces in Volume 2, 13 pieces in Volume 3, 12 pieces in Volume 4, 11 pieces in Volume 5 and 10 pieces in Volume 6. |

| 3. | ↑ | See Stephanus Muller, ‘Michael Blake’s String Quartets and the Idea of African Art Music’, Tempo 76:300 (2022), pp. 6-17, esp. pp. 15-16. |

| 4. | ↑ | Bartók is referenced specifically in: ‘Canon at the Octave [Trad. Arr. Blake]’ (no. 16, volume 2); ‘Latshon’ilanga (The sun has set)’ (no. 27, volume 2); ‘Postcards from South Africa’ (no. 41, volume 3); ‘Emerging Melody’ (no. 46, volume 4); ‘The Seven Steps’ (no. 55, volume 5); ‘Night Music’ (no. 68, volume 6); ‘Diary of a Dung Beetle’ (no. 71, volume 6) and ‘Dance in Seakhi Rhythm (Homage to Bartók and JP Mohapeloa)’ (no. 75, volume 6). |

| 5. | ↑ | Seminar notes, 29 September 2022, Africa Open Institute, Stellenbosch University. |

| 6. | ↑ | Examples are ‘Scents of Childhood 2 – Homage to Schumann’ (no. 59, volume 5), pp. 16-19); and ‘Scents of Childhood 3 – Homage to Schumann and Puccini’, (no. 70, volume 6), pp. 29-31. |

| 7. | ↑ | The piece, dedicated to Thalia Myers, is included as no. 34 in Volume 3 of Afrikosmos (p. 13), and described as follows in the Contents notes: ‘Translated as “concertina” in isiXhosa it is one of the many instruments imported and adapted for local use, often played by rural musicians who may be walking along the roadside, or played in bands together with guitars and other instruments’. |

| 8. | ↑ | Programme notes, NewMusicSA Afrikosmos Concert, 24 September 2022. |

| 9. | ↑ | There are exeptions, like ‘Sefapanosaurus’ (no. 4, volume 1), which is a graphic score and requires the pianist to wear woollen gloves. |

| 10. | ↑ | Blake is aware of this play on aural perspective, as is evident from his note on ‘Latshon’ilanga (The sun has set) (no. 26, volume 2), where he connects it with a Bartókian device of assigning the melody to the left hand and the accompaniment to the right hand. See also ‘Variations on a Flute Tune (no. 39, volume 3). In the two examples cited above, however, the very boundaries between melody and accompaniment are eroded, rather than registerally displaced. |

| 11. | ↑ | Christopher Alexander, The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe, Book One, ‘The Phenomenon of Life’ (Berkeley, California: The Center for Environmental Structure), 2002, esp. Chapter Five, entitled Fifteen Fundamental Properties, pp. 143-242. |

| 12. | ↑ | Ibid., pp. 158-59. |