PAULA FOURIE

Ghoema

“Ghoema had a huge impact. ‘Wow, we’ve been singing this stuff all these years, but we didn’t know where it came from.’ And Taliep was seen to be that guy.”[1]David Kramer, interview by the author, 1 November 2012.

In August 2004, Taliep [Petersen] and Herman [Binge] staged a piece at the Jannewales arts festival hosted by Jan van Riebeeck High School in Cape Town.[2]“Jannewales lok voorste kunstenaars”, Die Burger, 30 August 2004. Meant to explore the origins of Afrikaans songs from the perspective of coloured South Africans, it featured Herman as narrator, with Taliep and a Coon troupe providing the music. It also aimed to bring across the message that “Ons is eintlik maar net almal een mixed bunch” (We are really just all one mixed bunch.). The show opened with a listing of names – all the Afrikaner families with enslaved people among their early progenitors. This lasted all of five minutes.

With so many names on the list, most white Afrikaans audience members must have been able to identify personally with what was happening on stage. What it was asking them to understand is that they, too, were a creolising people; that those who had styled themselves Afrikaners were not as “pure” as they wanted to believe.

Herman recalls that, with his blessing, Taliep took the text for this piece to David Kramer. But Kramer and Petersen had walked divergent paths since Kat and the Kings. “We started to have very different opinions about what to do and how to do it,” David remembers. “And, like I say, for ten years we didn’t create anything together other than a run of the show.”

Excited by the possibilities offered by computers and television, Taliep did not share David’s seemingly exclusive commitment to the stage and to folk music. While Taliep had been working on O’se Distrik 6, Alie Barber and Joltyd, David had staged folk-orientated stage pieces like Die Ballade van Koos Sas and Karoo Kitaar Blues. And after Taliep saw the Buena Vista Social Club in New York, “he loved that thing”, David remembers. “So I said what we need to do is a Cape Town Buena Vista Social Club. Ja. He loved that idea. And then he kind of, he pursued it without me on his computer.”

Nearly twenty years after they had begun working together, Ghoema brought their collaboration to life again. “I always say that Ghoema took thirty years to write,” David points out. “For me, Ghoema was what I had wanted to do right from the beginning and which is what led me to District Six in the first place. It took twenty years for Taliep and I to amalgamate properly to have the same vision.”

Reflecting both men’s growing concern with the language, Ghoema was written predominantly in Afrikaans. It started out in the usual way, as David points out, “discussing and researching the subject and exploring the possibilities”. But adopting a workshop method even more generative than with Kat and the Kings, “we went into the rehearsal room, not with a script, as there were no characters at that point, but with research material and the skeleton of a structure”. This, incidentally, was something David remembers Taliep was wary of, at least initially. “He kind of felt that the people participating would then claim that they had created it.” The duo followed their by now established method in creating Ghoema’s original music. David came up with a lyric which Taliep set to music. It also incorporated existing Kramer–Petersen compositions like Blue Skies, originally written for the 1989 Cape Town album, and Marahaban, written back in 1994.

Rehearsals for Ghoema took place in a church hall in Salt River. “How it was going to turn out, I had no idea,” David reflects on his explorative workshop approach, “and Taliep was quite nervous about that, how it was going to turn out.” And, at first, it seemed to have done the show no favours, as his own biographers point out ominously: “right up to their departure for Oudtshoorn the musical seemed as if it was not going to pull through”.[3]Dawid de Villiers and Mathilda Slabbert, David Kramer: A Biography (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2011), 270.

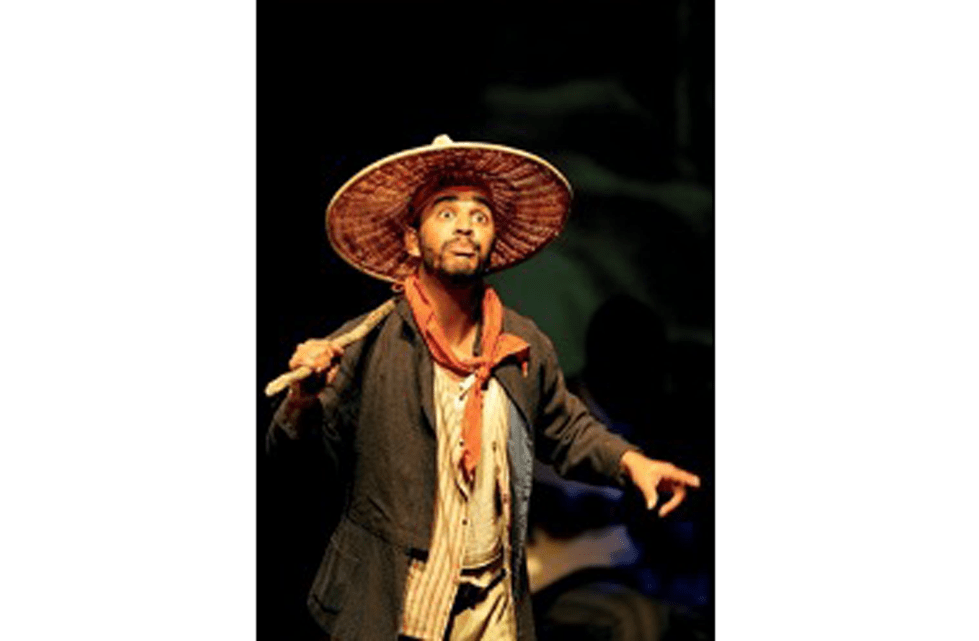

Ghoema! opened at the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees in March 2005, taking audiences on an hour-long exploration through the origins of Afrikaans and the contribution of enslaved people and their descendants to South African culture. Probably for the first time since Taliep had temporarily taken up a role in District Six: The Musical in the 1980s, audiences also got the chance to see him in one of his own shows. “At the back of the stage there was a raised platform for the musicians,” Mannie Manim, who was in the audience, recalls. “Taliep sat in the centre, and he shone. His beautiful face and his clear lyrical voice soared above all the others.”

The Afrikaans daily Beeld agreed, claiming that watching Taliep was more interesting than watching the show’s five actor-singers on stage.[4]“Mag Kramer, Petersen se ‘Ghoema’ nie ophou praat”, Beeld, 30 March 2005. Judging from the rest of the review, this wasn’t because Munthir Dullisear, Zenobia Kloppers, Carmen Maarman, and Emo and Loukmaan Adams were not compelling in their own right. “Opvoedkundig, ja, maar sonder enige prekerigheid of dralerigheid,” it gushed. “Dit is vinnig en kleurryk en die laaste 10 of 15 minute is almal in elk geval op hul voete aan ’t sing en handeklap.” (“Educational, yes, but without any preaching or ponderousness. It is fast and colourful and in the last 10 or 15 minutes everyone is on their feet anyway busy singing and clapping hands.”) Ghoema!, even in its first manifestation, was a resounding success.

After KKNK, Taliep and David extended the musical to two hours and changed its name to Ghoema. This version played in the Baxter Theatre from 11 November 2005. Directed by Kramer, and with musical direction by Taliep, it starred some old faces and some new. Leading the edutainment were actor-singers Loukmaan Adams, Munthir Dullisear, Zenobia Kloppers, Gary Naidoo and Carmen Maarman.[5]Programme for David Kramer and Taliep Petersen’s Ghoema at the Baxter Theatre, Cape Town, 11 November 2005 – 7 January 2006, TPC, DOMUS, US. The band consisted of Danny Butler, Gammie Lakay, Howard Links, Solly Martin and Charlie Rhode. Set design was by David Kramer (under the alias Julian Davids), lighting design by David and Gert du Preez, costume design by Illke Louw, choreography by Loukmaan Adams and props by Jesse Kramer. Again, the show thrilled audiences and critics alike. Described as “a musical history lesson that wows”, it was praised in particular for engaging with the early history of the Cape in a production that was as educational as it was entertaining.[6]Rafiek Mammon, “Kramer and Petersen’s best yet”, Cape Times, 21 November 2005; Bob Eveleigh, “‘Ghoema’ sparkles with sharp comedy, song”, The Herald, 2 December 2005.

In interviews, Taliep frequently repeated his concerns about Afrikaans, giving quotes that could just as well have been about Alie Barber, Joltyd or one of the television shows still being conceptualised.

“There is a huge misconception among people that Afrikaans is the oppressor’s language,” he told The Argus. “But they don’t understand that the slaves also used the language and made a major contribution to this country. We know the names Van Riebeeck and Dias but do we know the names of the slaves who were with them?”[7]Salie Igsaan, “A new take on the history of our liedjies: Show reveals enormous impact slaves had on the Cape”, Weekend Argus, 5 November 2005.

From the vantage point of a present-day New Year’s Eve, Ghoema tells its story through song and dance, interweaving dialogue and humorous sections of rap with original compositions and folk songs. The perspective is that of Cape Town’s coloured population.

Beginning with the establishment of a refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope, the story is about the growth of a slave society at the Cape, replete with a large body of folk songs that developed on its farms. It spans the creation of Afrikaans in the kitchens of slave-owning households and the development of cuisine and architecture at the Cape, the emancipation of slaves by the British in the nineteenth century and the impact this had on the Afrikaners’ decision to embark on the Great Trek with their “former” slaves. “Wie gaan saam met die ossewa? (Who is joining us on the ox wagon?)” indeed, as that old ghoemaliedjie asks. The musical remembers the role of slaves in providing musical entertainment to colonists and how they entertained themselves at picnics. It explains how musical forms such as the Indonesian keroncong made their way to the Cape, how Dutch songs continued to arrive along the ocean routes, and the impact of blackface minstrelsy when it, too, arrived. Most importantly of all, it traces the impact of all of this on the Coon Carnival and Malay choir traditions.

Even though Ghoema contains some original Kramer–Petersen songs, it teems with nederlandsliedjies, ghoemaliedjies and moppies. These song forms also found their way into many of the original compositions. ‘Blue Sky’, for example, is an arrangement of an old nederlandsliedjie, while ‘Nuwe Naam‘ (New name) has the ghoemaliedjie ‘Januarie Februarie Maart‘ (January February March) as its chorus. Nevertheless, as David remembers, Taliep “wasn’t keen on doing the traditional songs. He wanted to do Ghoema with more original songs, which there were in Ghoema. But ja, at first … I mean, when we had finished Ghoema, he was very proud of that piece of work and, you know, saw it as a triumph.”

Knowing Taliep as I do by now, I imagine that this perceived reluctance had something to do with his ambition. Instead of writing original material, he was again arranging and rearranging a body of familiar songs that he knew back to front and inside out. Behind him was a lifetime of performing covers and working with the traditional material considered emblematic of the “population group” to which he was assigned by apartheid. Perhaps, at fifty-five, he only wanted to write music that was his own, that contained everything that made him, not necessarily coloured, but that made him Taliep Petersen.

But Ghoema had a different agenda. With much of its traditional material associated with the coloured population, the musical also foregrounds the folk songs shared by both coloured and white Afrikaans speakers, demonstrating that enslaved people played a crucial role in their creation. It offered proof of this by revealing the hidden messages embedded in the lyrics of these songs.

This includes ‘Suikerbos, ek wil jou hê‘, ‘Vanaand gaan die volkies koring sny‘ and ‘Solank as die rietjie in die water lê‘, all of which can be found in the FAK-sangbundel.[8]Nuwe FAK-sangbundel, ed. Dirkie de Villiers et al. (Cape Town: Nasionale Boekhandel, 1961), 463, 465, 483. There, they are listed as South African folk songs, arranged by white Afrikaans composers like Dirkie de Villiers. “Baie van ons goete (Kaaps-Maleise liedjies) is daarin,” Taliep lamented the following year.[9]Hanlie Retief, “Afrikaans deur dik en dun”, Rapport, 26 February 2006. “Ons het dit niks gelaaik nie. Dis die hele ding van vat wat nie aan jou behoort nie. Ek het al boeke gesien met die naam Bóéresangbundel, dan wemel dit van Maleise musiek. My mense het wég gevoel daarvan. Ons is nié FAK nie (A lot of our things [cape Malay songs] are in it. We didn’t like it at all. It’s that whole thing of taking what doesn’t belong to you. I have seen books before with the name Boere Songbook, then it teems with Malay music. My people felt alienated from that. We are not FAK)”.

Just as Ghoema educated audience members in the creole origins of Afrikaans, part of the musical’s subversiveness lay in a similar rehabilitation of these folk songs by demonstrating that they were also – if not even more so – the cultural property of those who came to be known as coloured.

How would an audience have reacted to this, seeing its potential to upset cherished notions of Afrikaner cultural heritage? That depends on what a typical Ghoema audience looked like. At KKNK, it would have reflected the profile of the festival; as such, mainly older and white. At the Baxter, meanwhile, as David remembers, audiences were “very mixed”, with “probably a coloured majority overall”.

When I ask him over email about the audience response, David remembers that festival-goers were “very positive and enthusiastic”. He also remembers what Ton Vosloo of the Afrikaans media conglomerate Naspers said to him after the show: “Jy’t die mense op ’n mooi manier vertel waarvandaan die taal kom (You told the people in a nice way where the language comes from)”.

“My impression,” he writes, “was that our version of the roots of Cape creole (Afrikaans) and the introduction of the contribution that was made by slaves was shocking for some and hugely liberating for others. It’s possible that a few whites were uncomfortable with this perspective. But the general reaction was enthusiastic. It was a huge box office success and travelled internationally. For coloured audiences, it conveyed a secret history. It was reaffirming. That it celebrated a topic and a history which people had suppressed and felt shameful about was liberating. It had an enormous impact on the way people saw themselves and their place in this South African story. My experience of developing this piece in rehearsal was that, although the musicians and singers had been deeply involved in their traditions (for example the “Malay” choirs, klopse, nagtroepe, etc.), they were completely in the dark about the history and origins of these traditions. Their personal family histories were also limited. Almost all the research that was brought into the rehearsal room was a revelation to them. And this is probably what the reaction was for most of our audiences.”

Ghoema presented white Afrikaans speakers with evidence of their involvement in creolisation that was hard to deny. And if it claimed that white Afrikaner heritage was in reality also coloured heritage, it also suggested the converse, that much of what is regarded today as “coloured culture” is also their own.

In 2005, this must have been something of a revelation. Denis-Constant Martin has since pointed out that the musical history of Cape Town is “largely the result of a process of creolization that has been devalued and rejected by the ruling sections of the population but never wiped out”.[10]Denis-Constant Martin, “Cape Town: The ambiguous heritage of creolization in South Africa”, in Popular Snapshots and Tracks to the Past: Cape Town, Nairobi, Lubumbashi, ed. Danielle de Lame and Ciraj Rassool (Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa, 2010), 184. He argues that by denying their own participation in creolisation, on the one hand and, on the other, sending black Africans back to their supposed primordial cultures in the homelands, the ruling white minority by and large “gifted” the legacy of creolisation, in which all had taken part, to that segment of the population they would label as “coloured”.

But there is also the matter of what white South Africans chose to claim for themselves: Afrikaans, for example, or boeremusiek, whose creole origins were subsequently disavowed.[11]See Willemien Froneman, “Pleasure beyond the call of duty: Perspectives, retrospectives and speculations on boeremusiek” (doctoral dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, 2012), 49–76, on the creole roots of boeremusiek. The ambiguity that surrounds the heritage of creolisation is perhaps best illustrated with reference to the Cape Malay koesista and the Afrikaner koeksister – two related pastries that each occupy distinct domains marked by racial boundaries.

Ghoema negotiated this terrain to great acclaim. Yet whenever I listen to its songs or watch the filmed show, something in the smiles and exaggerated postures of its actors leaves me feeling uncomfortable. For me, at least a key part of creolisation never made it onto the stage. This is the sheer violence with which the indigenous and enslaved populations were ripped from their respective worlds, the cruelties – big or small – that they had to endure on a daily basis. The history that Ghoema presents to its audience can only be described as a painful one. Yet this is largely lost in the frenetic playing and dancing on stage. One clue to this erasure is located in the easy equation of the show’s success in conveying its “secret history” with its “huge box office success”. What would have happened if more people had been uncomfortable with its message, if the history of Afrikaans had not been presented in a “nice way”, as Ton Vosloo put it? But the audience was, after all, enjoined at the start of the musical by its hip-hop narrators, Hot and Tot, to “sit back, relax / Switch af jou sel, / Issie storie vannie ghoema / Wat os nou gaan vetel (sit back, relax / Switch off your cell / It’s the story of the ghoema / that we are going to tell)”.

The Afrikaans journalist Mariana Malan did relax, and was so uplifted that she titled her review “Ghoema stuur jou met lied in die hart huis toe (Ghoema sends you home with a song in the heart)”. [12]Mariana Malan, “Ghoema stuur jou met lied in die hart huis toe”, Die Burger, 18 November 2005.

If the musical taught white Afrikaans audience members that they had taken part in creolisation, it did so through musical anaesthesia. Stirred by rousing syncopated drum beats and soothed by romantic Dutch songs, Ghoema dulled the pain of complicity in slavery.

What was left was an emphasis that Afrikaners and formerly oppressed South Africans share ownership of their cultural treasures. That there are things common to both the oppressed and the oppressor is, in the final analysis, one of the few ways in which the former ruling class and their descendants can justify existing in privilege in the disfigured country of their birth.

How bewildering, then, that in the end, even though the show was presented as “Kramer & Petersen’s Ghoema”, the credits on the Baxter Theatre programme, the commercial DVD and a score of newspaper articles read like this: “Written & Directed by David Kramer / Musical Director: Taliep Petersen”.[13]Programme for David Kramer and Taliep Petersen’s Ghoema at the Baxter Theatre. One can only assume that Taliep and David came up with this billing together. But over the course of twenty years, Kramer–Petersen’s commitment to crediting each other jointly without making a formal distinction had shifted to the point where Taliep’s co-authorship of Ghoema was reflected only in his credit as musical director. “Issie myne nie, issie joune nie (It’s not mine, it’s not yours),” as that other ghoemaliedjie goes.

The above is an extract from Mr Entertainment: The Story of Taliep Petersen by Paula Fourie published with permission from Penguin Random House South Africa. Copyright: Paula Fourie.

| 1. | ↑ | David Kramer, interview by the author, 1 November 2012. |

| 2. | ↑ | “Jannewales lok voorste kunstenaars”, Die Burger, 30 August 2004. |

| 3. | ↑ | Dawid de Villiers and Mathilda Slabbert, David Kramer: A Biography (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2011), 270. |

| 4. | ↑ | “Mag Kramer, Petersen se ‘Ghoema’ nie ophou praat”, Beeld, 30 March 2005. |

| 5. | ↑ | Programme for David Kramer and Taliep Petersen’s Ghoema at the Baxter Theatre, Cape Town, 11 November 2005 – 7 January 2006, TPC, DOMUS, US. The band consisted of Danny Butler, Gammie Lakay, Howard Links, Solly Martin and Charlie Rhode. Set design was by David Kramer (under the alias Julian Davids), lighting design by David and Gert du Preez, costume design by Illke Louw, choreography by Loukmaan Adams and props by Jesse Kramer. |

| 6. | ↑ | Rafiek Mammon, “Kramer and Petersen’s best yet”, Cape Times, 21 November 2005; Bob Eveleigh, “‘Ghoema’ sparkles with sharp comedy, song”, The Herald, 2 December 2005. |

| 7. | ↑ | Salie Igsaan, “A new take on the history of our liedjies: Show reveals enormous impact slaves had on the Cape”, Weekend Argus, 5 November 2005. |

| 8. | ↑ | Nuwe FAK-sangbundel, ed. Dirkie de Villiers et al. (Cape Town: Nasionale Boekhandel, 1961), 463, 465, 483. |

| 9. | ↑ | Hanlie Retief, “Afrikaans deur dik en dun”, Rapport, 26 February 2006. |

| 10. | ↑ | Denis-Constant Martin, “Cape Town: The ambiguous heritage of creolization in South Africa”, in Popular Snapshots and Tracks to the Past: Cape Town, Nairobi, Lubumbashi, ed. Danielle de Lame and Ciraj Rassool (Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa, 2010), 184. |

| 11. | ↑ | See Willemien Froneman, “Pleasure beyond the call of duty: Perspectives, retrospectives and speculations on boeremusiek” (doctoral dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, 2012), 49–76, on the creole roots of boeremusiek. |

| 12. | ↑ | Mariana Malan, “Ghoema stuur jou met lied in die hart huis toe”, Die Burger, 18 November 2005. |

| 13. | ↑ | Programme for David Kramer and Taliep Petersen’s Ghoema at the Baxter Theatre. |