CHANTAL WILLIE-PETERSEN

BHEKI MSELEKU: an infinite source of knowledge to draw from

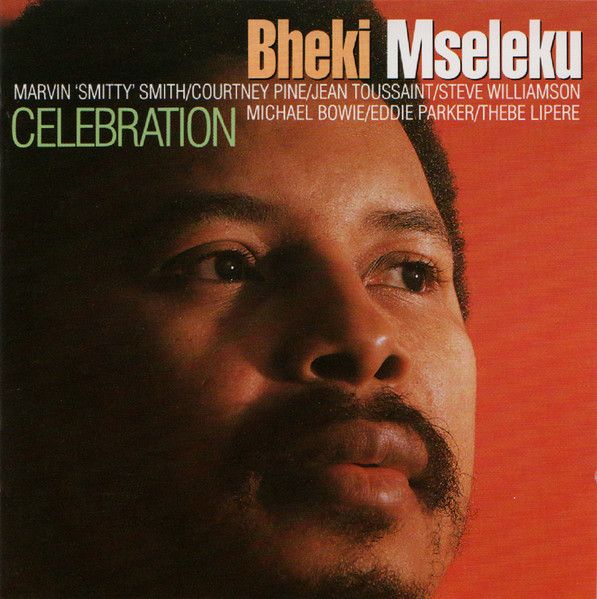

On the cover of Andrew Lilley’s The Artistry of Bheki Mseleku (2020) is a blurred black and white portrait by renowned jazz photographer Siphiwe Mhlambi of the mesmerising South African jazz pianist, virtuoso composer and multi-instrumentalist Bhekumuzi Mseleku (1955-2008).

With piercing eyes steadily composed above his mouth, meticulously framed at the tip of a microphone, what one of South Africa’s most global jazz musicians of the Twentieth Century is about to sound (sing or speak) – is paradoxically unheard: in a literal sense (as we have no audible sound), but also in a metaphorical and symbolical way. This picture juxtaposes a local dichotomy: that although many South African jazz figures are revelled in and revered – significant portions of their musical works receive limited archive space due to previous censorship laws, or, as South African jazz pianist and author of this work, Andrew Lilley, articulates, if studied, few to no works on prolific South African historical jazz figures amplify and explicate detail on how their artistry can be understood relationally, using transcription and music-theoretical analysis. In a sense, their musical sounds remain mystical concepts with hidden truths yet to be disclosed.

Equally compelling is Lilley’s book title which gets us to unpack the questions: What is artistry? How is it defined – musically, pianistically, and within the Trans-Atlantic sharing of jazz, historically? Merriam-Webster defines artistry as “artistic quality of effect or workmanship”, using synonyms such as “adeptness, craft, cunning, deftness, masterfulness, skilfulness, adroitness, art, artifice”.[1]artistry For Lilley (59:2020), an exemplification of Bheki’s artistry is explained when he writes, “While Mseleku’s style is clearly influenced by the Afro-American jazz school, his South African roots[2]My italics. are what truly define his art”.[3]Though Lilley sees Bheki’s work as firmly based in traditional South African and Afro-American jazz roots, he sites other influences in Bheki’s music such as Latin-based, Western-Classical (Romantic) music and streams of the “world music” genre. And that “…His comprehensive mastery of the jazz idiom, combined with his home roots,[4]My italics. has created a unique voice that has become the inspiration for many young South African artists seeking a relevant identity in the style…”(Lilley, xii:2020).

Amplifying this point, Lilley states “The fact that we are able to identify an artist by their sound and melodic approach is already indicative of a consistency that is present and that speaks to an overall character [of an artist]” (ibid: xiii:20202).

In the Foreword to Lilley’s book, South African jazz vocalist and composer, Nomfundo Xaluva heralds Lilley’s seven-chapter rendition as a harbinger and baton that provides a compelling representation, a dense and expansive analysis of over twenty of Mseleku’s compositional and improvisational works and a timely canalisation and homage to South African jazz and South African music as a whole. Xaluva further distinguishes Lilley’s reading of Bheki’s music as a spiritual (and cardinal) mouthpiece and her insinuation is poignantly analogous to South African pianist Ndudozo Makhathini’s pioneering discourse on the musical contribution of Bheki Mseleku, Encountering Bheki Mseleku: A Biographical-analytical consideration of his life and music[5]Encountering Bheki Mseleku: A Biographical-analytical consideration of his life and music (2019), Masters Dissertation, The University of Stellenbosch, 2019. (2019).

What then, are some of the wonders[6]According to Agawu (2004: 267 – 268) music analysis is useful as “rather to overwhelm, entertain, amuse, challenge, move, enable indeed to explore the entire range of emotions, if not in actuality, then very definitely in simulated form, at a second level of articulation”. This quote is used in Lilley’s book. demonstrated in Mseleku’s workmanship as Lilley “…lift(s) the bonnet of the vehicle of [Bheki’s] music, [to] look inside…with curiosity, enthusiasm, and wonder…[at Bheki’s adroitness] put together [its effect] in a way that has a structure that can be analysed and explained…(xii:2020)” and how does Lilley “unpack a narrative that traces the clear developmental ideas, influences and concepts” (Lilley, xiii:2020) in Bheki’s music?

Lilley’s Preface provides an overview of Bheki’s discography; an explanation of the author’s approach to his interpretation of compositional and improvisation transcriptions; his use of chord nomenclature and rhythmic notation (including composite and comparative examples); and a contextualization of the book’s jazz-orientated theoretical practice. Furthermore Lilley motivates that “The choice to notate in a particular way must inevitably be informed by the overall concept of the tune” (xix-xx: 2020). This statement (though applied to Lilley’s example of composite and comparative rhythmic notations), [7]Lilley looks at, for example, the complexity in deciphering and translating appropriate rhythmic notation heard in jazz ballads. directs much of the reader’s expectation toward Lilley’s analytical framework used to describe Mseleku’s artistry.

Lilley contextualises his work as neither biographic nor humanistic in nature, and his Explanatory Notes distil useful guidelines pertaining to his adopted methodology (close readings of composition and improvisation texts using music-theoretical analysis), and Lilley’s weaving-in of Bheki’s own reflections[8]Lilley (2020) states that whether Mseleku subscribed to a particular theoretical practice and whether this informed Bheki’s work, is not the premise of the book’s analytical approach. Further, that the book’s transcription design is used as a framework for analyses underpinned by the discipline of jazz taxonomies. According to Lilley, his transcriptions serve as notated evidence of Bheki’s work..

In order to explicate Bheki’s musical processes, Lilley’s narrative presents twenty-three original music transcriptions of a topographic selection of Bheki’s recordings. These cohesive extracts illustrate a technical and critical navigation through four main literatures: South African jazz, African American jazz, Western-Classical and music-theoretical text.

PART ONE is called ANALYSIS OF COMPOSITIONS and comprises five chapters which focus on the attributes of Mseleku’s compositional style(s). PART TWO, called IMPROVISATION comprises the last two chapters of the book and here Lilley uses nine of Mseleku’s pieces to observe a myriad of improvisatory techniques and styles. Further, Lilley includes two Appendix sections: Appendix A which is a transcription of the dialogue taken from The South Bank Show – a documentary which serves as an insight into Mseleku’s personal views; and Appendix B which comprises a collection of complete transcriptions of over twenty of Mseleku’s compositions discussed in the book. Of particular interest is Makhathini’s (2019) encircling of Bheki’s deep spirituality – in other words, the binary nature of Bheki Mseleku’s music – as both art and spirituality.

Throughout Lilley’s two-tier chapter subdivision, Bheki’s musical approaches are thoroughly contextualised, and juxtaposed within and between the adjacent compositional slants of many foregrounding African American jazz predecessors and contemporaries, and within the bounds of African American jazz histographies and literatures. Applying dense and detailed comparisons drawn between six of Bheki’s albums recorded between 1991 and 2008, Lilley demonstrates specific musical overtures and discourse between, for example, Bheki Mseleku and American pianists McCoy Tyner (1938-2020), Thelonious Sphere Monk (1917-1982), Earl Rudolph “Bud” Powell (1924-1966), Bill Evans (1929 – 1980), trumpeter Miles Davis (1926 – 1991), saxophonist John Coltrane (1926-1967), and numerous seminal American jazz musicians’ works and approaches.

What is somewhat marginal in the book is that no Nguni transcriptions are set in dialogue with Mseleku’s music to show, how, exactly, Lilley traces Bheki’s South African roots and innovations compositionally and artistically. In other words, the “African rootedness” of Bheki’s artistry, as acknowledged by the author, is not as generously evidenced. Although Lilley (59:2020) writes on the influence of South African pianist, Abdullah Ibrahim, and presents transcriptions of South African trumpeter Feya Faku’s improvisational approach on Bheki’s piece Mamelodi (109; 150: 2020),one misses the opportunity to engage with the author’s thoughts, analysis and close reading on Bheki’s adaption of elements of Nguni musics.[9] In his article “Musical Bow; “Gora”; “Nguni Music”; “Hottentot Music”, Rycroft defines Nguni ‘as the name applied collectively to the Zulu, Swazi and Xhosa peoples of south-eastern Africa…offshoots are the Ndbele of Zimbabwe and the Ngoni of Malawi and Zambia’ (The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians Vol 13, Rycroft, 1981:197). This, to “highlight the interpretation and thinking of the artist visually within the framework of the harmonic structure of a tune” and to thereby, establish the ‘baseline’ of ‘musical strands’ of distinct South African jazz music vocabularies, and Mseleku’s masterfulness or skilful hybridisation of the harmony used in traditional South African jazz-style(s) that ushers in Bheki’s unique craft, and adeptness.

The question of unpacking and tracing, compositionally, the presence of indigenous musics’ sound in local jazz, that is … the role of Nguni musics vis-a-vis the development and interpretation of South African jazz composition in the latter half of the 20th century and in the 21st century, is demonstrated in the works of, for example, Sazi Dlamini[10]Dlamini’s work specifically pays attention to the application and the role of ‘jazz-influenced’ repertoires in articulating cultural identities in exile, as well as the legacies of these repertoires – focused around the Blue Notes (2010). The South African Blue Notes: bebop, mbaqanga, Apartheid and the exiling of a musical imagination, 2010, Sazi Stephen Dlamini. and Ndudozo Makhathini.[11] ibid. Both of their dissertations explore the interconnectedness of indigenous musics, South African jazz and American bebop/hardbop styles in the performance and composition of works by South African jazz progenitors using Nguni musics transcription.

Though Makhathini’s work (2019) renders less musical transcription than Lilley, he unpacks Bheki’s jazz hybridity in very defined examples such as “Mseleku’s high-pitched voice [being a] familiar feature within vocal chanting in traditional Zulu music”. Further, in describing Bheki’s rhythmic sensibility, Makhathini (2019) shares that “The compound metre feel is reminiscent of the music of the Nguni people of South Africa (Rycroft 1967)…Moreover, this movement is grounded in a distinctive triplet motion that draws on the Zulu indlamu or izangoma drumming and Bapedi of Southern Africa”. Furthermore, of Mseleku’s piano groove, Ndudozo states “…I also hear musical traces of the BaSotho and Zulu accordion music of the 1900s, later popularized in the 1970s in South Africa (Accordion Jive Special – Vol. 1, Electric Jive, 2015)…” and so on.

While Bheki’s musical mobility, identity and intersubjectivity (influences) are masterfully set within Lilley’s transcriptions of Bheki’s influences, perhaps a more extensive focus on Bheki’s local indigenous music threading would have presented a clearer showcase of the “…balance between [Bheki’s] individual actualization and mutuality” representationally. As substantiated by Michael Titelstad (1999)

… By analogy, any allegorization of a musical work is metonymic…there is an economy of exchange between singularity and wholeness in representational practice… Furthermore…it’s [the musical work’s] carefully sustained balance between individual actualization and mutuality.”[12]Representations of Jazz Music and Jazz Performance Occasions in Selected Jazz Literature, Masters Dissertation, Michael Titlestad (1999).

While Lilley (55:2020) firmly suggests that Mseleku’s albums have a distinct stream of South African rootedness and identity – this observation could be amplified by transcriptions of the specific indigenous South African musical styles adapted and revolutionised in the sound of Bheki’s homegrown jazz styles.[13]According to David Coplan (1985:22) “we must review the principles fundamental to traditional musics of Southern Africa as they are performed today and use them as the baseline in the analysis of urban stylistic change.” Similarly, Carol Muller states (2008:84-85) “…to unpack these strands of tradition requires a deep understanding of the diversity of musical traditions in South Africa…these traditions were divided by different linguistic configurations. Making the style distinctly South African were elements that reflected the strong connection between instrumental performance and vocal style[s]”.

In conclusion, Marc Duby’s recent review[14]Duby, Marc, 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the African Studies Association. (2022) of Lilley’s book sums up, and I concur,

“These are resources of inestimable value in understanding Mseleku’s uniqueness as a major South African jazz musician… [and] as such, [Lilley’s book] may well serve as an exemplar for future analyses of local musical practices and stands as a first-rate contribution to jazz scholarship”.

Lilley’s authorship is a comprehensive dialogue which maps-through Bheki Mseleku’s compositions, unveiling many textual confluences and illustrating the effect of Bheki’s “superb [musical] choreography, and [compositional] stage design” (Lilley 4:2020). The idea of Mseleku’s musical identity is evidenced as we begin to “read and see”, and understand Bheki’s “becoming” musically. Lilley’s book emphatically helps us explore Bheki’s “self-in-process” …musically; his music as a “mobile process” and his sound as more than “static” compositional works.

Here, in order to endorse the far-reaching value of Lilley’s work, I draw on acclaimed ethnomusicologist Kofi Agawu’s argument[15]Kofi Agawu (2003) in Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (New York and London): Routledge, 2003. that

“… to understand the ways in which creative musicians assemble their music…we need to pursue in technical detail the process of composition. Without analysis such pursuit is not possible… [and that]…competing transcriptions of publicly available compositions form the basis of informed, vigorous contestation of appropriate modes of representation”

(Agawu 2003:18)

While over the last four decades several studies on local jazz, have been published and South African jazz historiography has received careful attention from a dedicated group of scholars globally, most works make limited use of analysis – when compared to that done by Lilley, and more importantly, this text adds significantly to a much needed corpus and archive of South African music.[16]Washington’s work is especially important because Mseleku’s music introduces the encounter between exiles and inxiles after the end of apartheid in his collaborations with musicians who remained in South Africa under apartheid. Washington, Salim ‘Exiles/Inxiles: Differing Axes of South African Jazz during Late Apartheid’ in SAMUS, 32(1), 91-111, 2012.

In The Fundamental Function of Music (2009), Emery Schubert[17]“The fundamental function of music” shares that music can be defined as an auditory stimulus whose fundamental function is to activate numerous rich memories and emotions that are experienced. The New York Times (2022) article on Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov, now a refugee in Germany, explains how his music and compositions have “taken on new significance for listeners”. As Russia’s war against Ukraine intensifies, Silvestrov states that “his sober, reflective compositions have become relevant [non-static] … as consoling music in the war-torn Ukraine.”[18]“Ukraine’s Most Famous Living Composer is now a Refugee” by Peter Schmelz March 30, 2022, New York Times.

Silvestrov has become a musical spokesperson for his country, with his compositions sounding and speaking prophetically over both the present and future possibilities of his displaced nation.

As with Silvestrov’s Prayer for Ukraine, we similarly, appreciate Andrew Lilley’s confirmation of Mseleku’s musical spokesmanship as a “mouthpiece” globally.

As a South African post-apartheid musician who lived abroad for more than a decade, there is commonality in searching for identity and “belonging” and (re)-presenting one’s artistry compositionally and sonically. Lilley’s authoring on Bheki Mseleku’s cinema of “home” provokes our understanding of composition as an agent and mouthpiece to augment our own impassioned notions of “home”. In March this year, acclaimed carillonist Tiffany Ng premiered the first carillon works ever written by Black South African composers at the University of Michigan. Called Your Rhythm Is Rebellion: Ringing in Postcolonial Carillon Solidarity, this landmark concert featured commissioned works by South African composers Bongani Ndodana-Breen, Kendall Williams and I. The event not only amplified the creativity of Black composers,[19]‘Your Rhythm Is Rebellion’ but allowed the compositional representation (sound) of the carillon bell toward a more inclusive representation than its previous and historic sonic exclusion. My composition “Kloppe Roep” was written for the enslaved women at the Cape and attempted to capture the dissonant and rhythmic monotony of slavery while tooling sound as a mouthpiece to articulate new belongings and in a sense, new musical “homes” as women embrace new dispensations. The representations of individual and collective histories that question why certain sounds (elements of musical properties) allow us to reflect on “home” (as a physical sound and or musical/spiritual place) – is addressed in Lilley’s work, as he navigates the road toward “how the sounding of our collective histories through composition” can speak to musical identity, a cultural diaspora in a globalized era, thoughtfully and intentionally.

Simon Frith[20]Performing Rites: Harvard University Press, 1996. notes, musical identity “is mobile, a process not a thing, a becoming not a being … our experience of music – of music making and music listening – is best understood as an experience of this self-in-process” (1996:109).

Andrew Lilley’s The Artistry of Bheki Mseleku (2020) calibrates Bheki’s sonic genius within a funnel of understanding around the composer’s intersubjectivity, identity and multiple modes of thinking through South African jazz.

This highly specialized handbook, augments our thinking and reading around South Africa jazz and the catechism or capacity for music-analytical texts to exhume not only the spiritual essence of Mseleku’s and South African jazz music, but to perceive and identify new perspectives and specificity in our own homegrown music and compositional works, attesting to the power of these musical works and compositional representations (in sound) to bring about inclusive representation around memory and identity.

This book lays vivid tracks which amplify South Africa’s musical heritage as a myriad of self-in-process portraits of rich, national artworks and human virtuosity. Bheki Mseleku’s offerings are, as Lilley puts it, an “infinite source of knowledge to draw on”.[21]I draw on Chats Devroop and Chris Walton’s (2007:6) and Carol Muller’s (2008:148) views when stating that the challenge to research and investigation in this field of study remains the arguably poor, dispersed documentation and availability of extensive jazz composition text for analysis..

| 1. | ↑ | artistry |

| 4. | ↑ | My italics. |

| 3. | ↑ | Though Lilley sees Bheki’s work as firmly based in traditional South African and Afro-American jazz roots, he sites other influences in Bheki’s music such as Latin-based, Western-Classical (Romantic) music and streams of the “world music” genre. |

| 5. | ↑ | Encountering Bheki Mseleku: A Biographical-analytical consideration of his life and music (2019), Masters Dissertation, The University of Stellenbosch, 2019. |

| 6. | ↑ | According to Agawu (2004: 267 – 268) music analysis is useful as “rather to overwhelm, entertain, amuse, challenge, move, enable indeed to explore the entire range of emotions, if not in actuality, then very definitely in simulated form, at a second level of articulation”. This quote is used in Lilley’s book. |

| 7. | ↑ | Lilley looks at, for example, the complexity in deciphering and translating appropriate rhythmic notation heard in jazz ballads. |

| 8. | ↑ | Lilley (2020) states that whether Mseleku subscribed to a particular theoretical practice and whether this informed Bheki’s work, is not the premise of the book’s analytical approach. Further, that the book’s transcription design is used as a framework for analyses underpinned by the discipline of jazz taxonomies. According to Lilley, his transcriptions serve as notated evidence of Bheki’s work. |

| 9. | ↑ | In his article “Musical Bow; “Gora”; “Nguni Music”; “Hottentot Music”, Rycroft defines Nguni ‘as the name applied collectively to the Zulu, Swazi and Xhosa peoples of south-eastern Africa…offshoots are the Ndbele of Zimbabwe and the Ngoni of Malawi and Zambia’ (The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians Vol 13, Rycroft, 1981:197). |

| 10. | ↑ | Dlamini’s work specifically pays attention to the application and the role of ‘jazz-influenced’ repertoires in articulating cultural identities in exile, as well as the legacies of these repertoires – focused around the Blue Notes (2010). The South African Blue Notes: bebop, mbaqanga, Apartheid and the exiling of a musical imagination, 2010, Sazi Stephen Dlamini. |

| 11. | ↑ | ibid. |

| 12. | ↑ | Representations of Jazz Music and Jazz Performance Occasions in Selected Jazz Literature, Masters Dissertation, Michael Titlestad (1999). |

| 13. | ↑ | According to David Coplan (1985:22) “we must review the principles fundamental to traditional musics of Southern Africa as they are performed today and use them as the baseline in the analysis of urban stylistic change.” Similarly, Carol Muller states (2008:84-85) “…to unpack these strands of tradition requires a deep understanding of the diversity of musical traditions in South Africa…these traditions were divided by different linguistic configurations. Making the style distinctly South African were elements that reflected the strong connection between instrumental performance and vocal style[s]”. |

| 14. | ↑ | Duby, Marc, 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the African Studies Association. |

| 15. | ↑ | Kofi Agawu (2003) in Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (New York and London): Routledge, 2003. |

| 16. | ↑ | Washington’s work is especially important because Mseleku’s music introduces the encounter between exiles and inxiles after the end of apartheid in his collaborations with musicians who remained in South Africa under apartheid. Washington, Salim ‘Exiles/Inxiles: Differing Axes of South African Jazz during Late Apartheid’ in SAMUS, 32(1), 91-111, 2012. |

| 17. | ↑ | “The fundamental function of music” |

| 18. | ↑ | “Ukraine’s Most Famous Living Composer is now a Refugee” by Peter Schmelz March 30, 2022, New York Times. |

| 19. | ↑ | ‘Your Rhythm Is Rebellion’ |

| 20. | ↑ | Performing Rites: Harvard University Press, 1996. |

| 21. | ↑ | I draw on Chats Devroop and Chris Walton’s (2007:6) and Carol Muller’s (2008:148) views when stating that the challenge to research and investigation in this field of study remains the arguably poor, dispersed documentation and availability of extensive jazz composition text for analysis. |