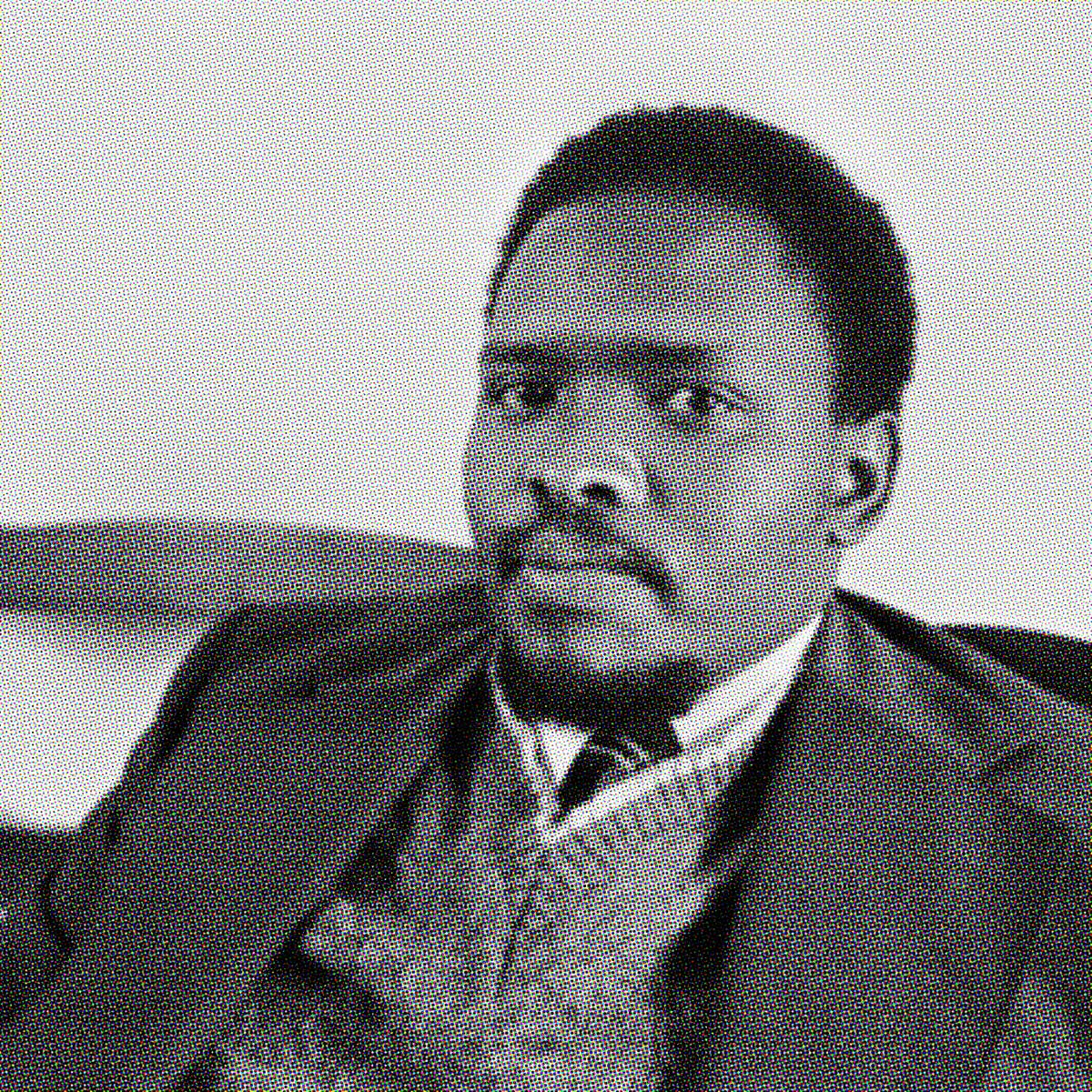

NDUMISO MDAYI

Biko and the Hegelian dialectic

“The first step, therefore, is to bring the black man back to himself.”

Steve Biko. We Blacks. I Write What I Like

When Steve Biko is read or used for political and cultural ends which are contrary to what the man stood for, it becomes important in our work of critical thought, to bring him back to himself; wallowing in the contradictions, to ultimately craft a philosophy of revolutionary praxis. This article explores Biko’s application of Hegelian dialectics in thinking through the condition of black people in South Africa. While, in the first instance, it argues along with Biko that the thesis in South Africa is white racism or whiteness, it further encourages us to think in terms of the structure of antiblackness and consider racial slavery as the fundamental contradiction.

As president and head of publication of South African Students’ Organisation (SASO), Steve Biko was entrusted with the task of clarifying the political position of the organisation, which, in its opposition to white racism, can be summarized as a critique of the white liberal establishment and a critique of black people who want a seat at the white man’s table. This is because SASO saw white liberals, first and foremost, as white people who were interfering in the affairs of black people, and who went as far as to also prescribe the ways in which black people ought to respond to the problem of anti-black white racism in South Africa. In the essay ‘White Skins Black Souls?’ Biko writes:

A game at which the liberals have become masters is that of deliberate evasiveness. The question often comes up “What can I do?” If you ask him to do something like stopping to use segregated facilities or dropping out of varsity to work at menial jobs like all blacks or defying and denouncing all provisions that make him privileged, you always get the answer “But that’s unrealistic!” While this may be true, it only serves to illustrate the fact that no matter what a white man does, the colour of his skin – his passport to privilege – will always put him miles ahead of the black man. Thus, in the ultimate analysis no white person can escape being part of the oppressor camp.

Biko, 2004: 24

When we look into the history of oppression in South Africa, particularly how white settlers invaded African land, dispossessed, and conquered Africans in wars, we can then argue that apartheid wouldn’t had been possible without settler colonialism as a structure, preceding institutionalized separate development. Moreover, since white settlers are the minority in South Africa, and often harbour fantasies of extinction, it makes sense that whites are therefore invested in maintaining the status quo or the paradigm of perpetual black suffering and death.

Black suffering and death provide white settlers with the stability needed for their comfort, renewal, integrity, and power.

Biko maintains that as a result of centuries of oppression, blacks “will be useless as co-architects of a normal society where man is nothing else but man for his own sake.” (Biko, 2004: 22).

SASO developed “Black” as a political identity which was a negative dialectic to white. This was during a time in apartheid South Africa when people were classified as either white or non-white, or as European and non-European. Furthermore, Vladimir Lenin’s reading of Hegelian dialectics as “a unity of opposites” which are “historically observable” and “mutually exclusive,” (Lenin, 1915) will perhaps be helpful in our reading of Biko’s application of the Hegelian dialectic.

“Black” and “white” are therefore in a unity but as opposites and mutually exclusive. In a Kantian sense, the categories through which we think and understand the politico-ontological positions of the oppressed as black and of the oppressor as white, are therefore not permanent. The conception of an “egalitarian society” or the bestowing upon South Africa “a more human face” (Biko, 2004: 96, 108, 158, 166) allude then to the temporariness of both blackness and whiteness as political identities, where the Fanonian tabula rasa and a new language of humanity must make possible the transition from black social death (on which the existence of the white depends) to an acquisition of a new symbolic form. In this sense, Biko can be read as refusing to inherit race, as that would mean an indebtedness to anti-black settler colonial conceptual frameworks.

In the essay ‘Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity’ Biko expands on SASO’s adaptation of Hegelian dialectics to the South African situation:

For liberals, the thesis is apartheid, the antithesis is non-racialism, but the synthesis is feebly defined. They want to tell the blacks that they see integration as the ideal solution. Black Consciousness defines the situation differently. The thesis is in fact a strong white racism, and the antithesis to this must, ipso facto, be a strong black solidarity amongst the blacks on whom this white racism seeks to prey. Out of these two situations we can therefore hope to reach some kind of balance – a true humanity where power politics will have no place.

Biko, 2004: 99

In this sense, we can see Biko moving from the Fanon of Black Skin, White Masks to the Fanon of The Wretched of the Earth. In the former, there is no recognition or reciprocity as it is the case with Hegel. The black is caught in a racial drama of identification with whiteness, and this identification providing a unified image of the once lacking or fragmented black body. There is then a psychic community where whites and blacks are bonding over the black phobic object. (Marriott, 2007: 209, 211).

In the same way, this can be seen in colonial apartheid South Africa, where identification with whiteness causes the black to continually negate its own blackness. Biko sees this identification, instead, as “inculcat[ing] in the black man a sense of self-hatred which […] is an important determining factor in his dealings with himself and his life.” (Biko, 2004: 113). When Biko writes about “a strong black solidarity,” this can be read as an evocation of Fanon’s decolonization, where the black must use violence as a means to resist white racism, and to liberate the self.

It should also be noted that in the case of the liberals Biko disagrees with above, who, in their application of Hegelian dialectics, defined the synthesis “feebly,” non-racialism could perhaps be an antithesis and also synthetically become the new thesis. The problem is not therefore a poorly defined synthesis, but the assumptive logic that underlies the notion of non-racialism, as a response to anti-black white racism. Non-racialism operates from the assumption of a shared vulnerability to violence.

Elsewhere in the book, however, Biko does criticize whites who insist on non-racialism. He sees them as refusing to take responsibility for the oppression of black people, “claim[ing] that they too feel the oppression just as acutely as the blacks and therefore should be jointly involved in the black man’s struggle for a place under the sun…” (Biko, 2004: 21).

It is unsurprising that this is the same ideology of non-racialism that is embedded into legal, social, political, and economic structures of South Africa today. This is essentially because 1994 did not mean an end to settler colonialism and apartheid, and to the racial slavery that underlies both.

1994 was indeed “a nonevent of emancipation.” (Hartman, 1997: 116).

When Biko writes about the synthesis being the result of an interplay between white racism and black solidarity – or simply, a true humanity – this also shows Biko and SASO’s difficulty in finding a language to describe, in essence, what this true humanity entails. This difficulty to describe or even make political calculations for what is to come, alludes to Fanon’s notion of invention. It is for this reason that Fanon’s theory of violence should not merely be understood as a politics of liberation or resistance, but as a discourse of invention. (Marriott, 2014). In the opening chapter of The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon writes:

It is true that we could equally well stress the rise of a new nation, the setting up of a new state, its diplomatic relations, and its economic and political trends. But we have precisely chosen to speak of that kind of tabula rasa which characterizes at the outset all decolonization. Its unusual importance is that it constitutes, from the very first day, the minimum demands of the colonized. To tell the truth, the proof of success lies in a whole social structure being changed from the bottom up. The extraordinary importance of this change is that it is willed, called for, demanded.

Fanon, 1963: 35

Surely then, in crafting a philosophy of revolutionary praxis, we must also have the courage to read closely and allow ourselves to wallow in the contradictions, to ultimately find ourselves again.

In the case of these selves not being familiar, where we are without words or language to describe them, we will then be in the time of invention. Revolutionary praxis must be a politics of refusal – a dialectical negation of time.

Biko, S. 2004. I Write What I Like. Johannesburg: Picador Africa

Fanon, F. 1963. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Constance Farrington. New York: Grove Press

Hartman, SV. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press

Lenin, V. 1915. On the Question of Dialectics. Marxist Internet Archive.

Marriott, D. 2007. Haunted Life: Visual Culture and Black Modernity. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press

Marriott, D. 2014. No Lords A-Leaping: Fanon, C.L.R. James, and the Politics of Invention. Humanities vol. 3, pp. 517–545. DOI:10.3390/h3040517