MARKO PHIRI

Bulawayo’s movement of Jah People

Bulawayo, ZIMBABWE – The history of Bulawayo’s reggae sound systems is a history of artistic improv. Young men who fashioned themselves as virtuosos of the mic, MCs who chanted – or toasted – off the top of their heads became part of a movement recalled with nostalgia by the city’s own remaining “reggae greats.” These were young men growing up in the city’s poor townships enamoured with all things patois and sought to bring the sound systems of Kingston, Jamaica’s ghettos to their own backstreets. Setting up the sound system required the genius of “brethren” who could build from their own backyards giant speakers, turntables and amplifiers cobbled from scratch using bits and pieces of electronic junk.

A sound system – or disco machine as others outside the reggae lexicon called it – was a humongous presence of anything up to ten giant speakers accompanied by a convoluted string of electric cables which only the doctor of sound knew which wire went where. However, the local sound system differed from its Jamaican influences where the DJ was both selector and chanter, whereas in Bulawayo the DJ’s duties were limited to spinning the vinyls on the turntable while the Mic Chanter (MC) took to the stage as described by Papa Victor, a local reggae elder who considers himself one of the city’s reggae repositories.

The DJ would call out to the crowd, inviting “wannabe MCs” to showcase their skills and “move the crowd” over a dub track. The DJ was essentially the engineer of sound, his autodidactic ear driving the sessions held in the city’s community halls. That was back in 1980s, 90s Bulawayo where reggae sound systems and stacks of 33 vinyls were the rage, long before pirated music entered the subconscious habits of consumers not willing or unable to pay for the lifestyles of their favourite artists. This was long before record bazaars folded their tents and disappeared into the sunset, long before the birth of ProTools and other technologies that have turned anyone and everyone into a melody maker. A rich oral history of the era is told by city elders who have accepted that “the good old days, you cannot get them back.”

“Every township had a reggae sound system back in the 80s and early 90s,” says Eric Phiri, a reggae elder who runs the only reggae shop in Bulawayo’s downtown CBD. “We held shows at the city’s community halls and anyone who felt they could chant would request the DJ to spin a dub instrumental and they would be given a microphone and do their thing,” Phiri said.

The DJ’s sonic sensibilities drove the aspirations of young chanters for whom drawing from the African diaspora extended to all kinds of musical stylings of the time, from rhythm and blues, to funk and rock and roll. Names such as Small Axe (named for Bob Marley’s famed 1970 song), Black Nyamen, Black Nyabinghi, Reggae Merchants, Dub Rockers, Black Disciples, Social Living, Children of Zion, Black Star Liners (named after Marcus Garvey’s troubled “Back to Africa” project) formed part of the sound system nomenclature, showcasing a yearning for connecting with youths in the impoverished slums of Kingston, Jamaica. After all, it has been written elsewhere that “the sound system [also] acts as a symbolic transmitter of shared experiences across the African diaspora”.

These sound systems thrived on a communal sharing of reggae music and the crews created whole libraries of reggae collections based on a simple logic: anyone who bought a record added it to the collective’s catalogue. “The sound system was our own way of pushing the culture and spread knowledge about reggae,” says Patrick Ncube who goes by the telling moniker “African Teacher,” and talking to him it wasn’t difficult to see why he had chosen Winston Rodney for inspiration.

Patrick says he and his Nyabinghi sound system crew, hosted every major reggae act that came to Bulawayo, from Abacush, to Eddie Fitzroy and Gregory Isaacs, hung-out with Aswad’s Brinsley Forde and led the team that welcomed Buju Banton at the local airport back in the 1990s. “We held chant competitions where gifted yout’ were given an opportunity to showcase their lyrical skills but some chose to lip sync and do covers of popular reggae songs when in fact we were looking for originality,” he told me from his stall outside Bulawayo’s City Hall where he sells flowers.

The wildly psychedelic reggae dubs identified with the city’s hard core enthusiasts were the signature sound of Lee “Scratch” Perry, Augustus Pablo, Mad Professor, King Tubby, Scientist, Black Ark, among a galaxy of reggae greats. The toasting and patois that found a home in Bulawayo’s townships was in the tradition of luminaries such as U-Roy, Jah Thomas, I-Roy, General Trees, Lieutenant Stichie and many Rastas from that generation, helping “spread the knowledge not just dance to nice beats,” as Phiri put it.

Some city Rastas however insist that the sound system was not a mere addendum to the culture as they interpreted it, but a conduit for introducing reggae to wider audiences. “The problem with the (sound system) dances was that some loved the mere outings at the local community halls but neglected to have a deeper appreciation of the Rasta livity and reggae’s message,” Phiri said. Yet there was a core element of the reggae yout’s devotion to the seven mansions for whom stereotypes and cynicism became embedded in popular consciousness.

It seemed to come with the territory that young men who spotted dreadlocks back then (still) and declared their fidelity to the Rastafari teachings were summarily dismissed as dopes who puffed marijuana like others puffed Madison, Kingsgate, Peter Stuyvesant, Benson and Hedges or any other popular cigarette brands of the day. At the community dances where Rastas sold all kinds of food stuff as part of fund raising initiatives for their small commune in one of the townships, Phiri recalled that unschooled cynics would quip: “Man you say you are Rasta but you eat meat!” Expectations were of a strict adherence to the vegetarian and vegan diets of Rastafari as expressed in the songs and interviews of the pioneers and legends who influenced their worldview.

It would only be later that they heard the anthem “you don’t have to be dread to be Rasta” that indeed they spotted dreadlocks only to open themselves to ridiculous epithets. “We spotted dreadlocks back then but I don’t need that now,” Phiri told me as deeply profound reggae sounds played in low tones in the background in the confines of his workshop. It is here where Phiri has built a name as the go-to guy for reggae paraphernalia and the kind of sandals elsewhere favoured by mendicant spiritualists. A few seconds into one track, I said to him, “I thought that was Buju’s Murderer,” to which he laughed and said, “Well this is the original.”

Knowledge has always formed the central thesis of the reggae/rasta movement, and the African Teacher told me: “one cannot claim to have been part of the movement and not read the Bible and other Rasta writings.”

Whereas other young men of that era (insert the X-Clan, the Native Tongues, Zimbabwe Legit and other rap artists whose dithyrambs were explicitly pro-Black) chose dashikis and kente cloth, for Bulawayo’s reggae sound system young men, it wasn’t dreadlocks that identified them as true Rastas, it was those khaki jackets where one gifted Rasta used oil paint to fashion images of icons that ranged from Marley to Tosh, Winston Rodney and Steel Pulse and many others. It was their own declaration that “I&I am Rasta and proud,” after all this wasn’t far from James Brown’s “say it loud, I’m Black and Proud” moment.

Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness resonated with their Rasta education, the kind they would never get in class. They could well have been following the late great Lee Perry’s declaration that:

“I went to school. I learned nothing at all. Everything I learned has come from nature.”

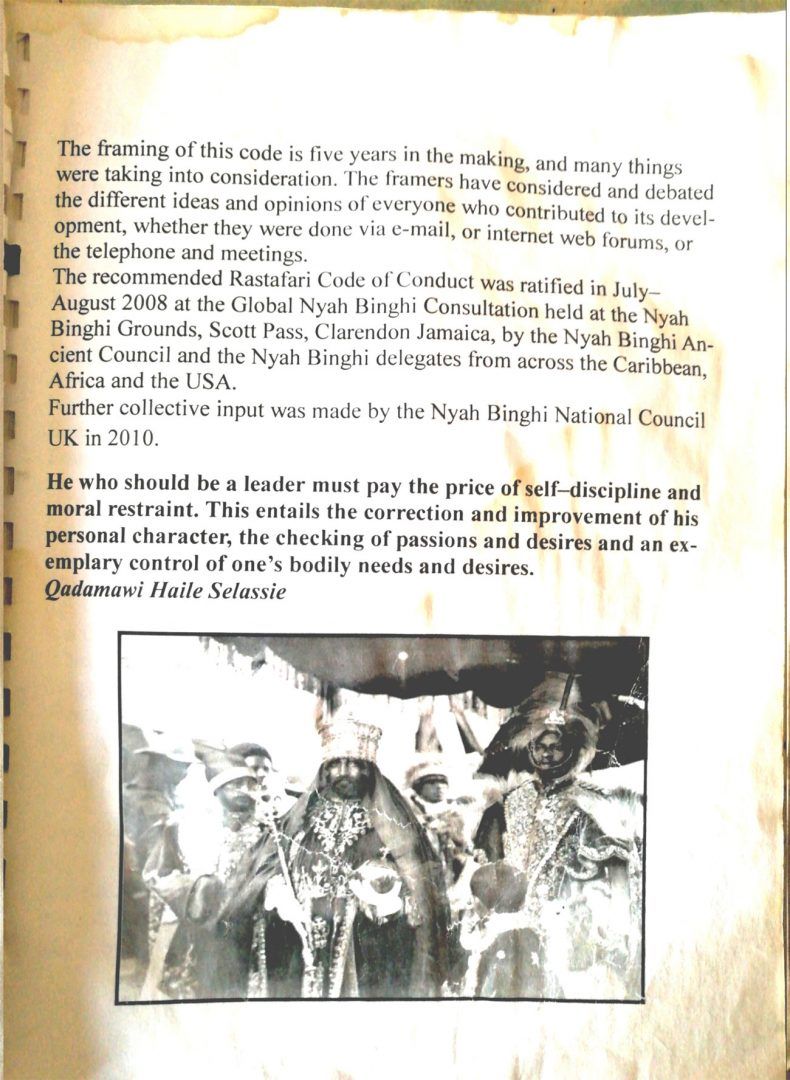

The writings of not just the Psalmist and the Old Testament but Marcus Garvey and Leonard Howell especially became staples for young men who did not particularly favour formal education. More than half a dozen Rastas I spoke to appeared eager to recite scripture and I got the sense that these elders, if not on a mission to proselytise, were only too keen to show off their devotion to the holy scrolls.

By their own renditions, as the ghetto awareness to Chant Down Babylon as Marley put it, the radicalism of Walter Rodney’s writings would emerge as the go-to-intellectual for Bulawayo’s young Rastas, with one Rasta elder telling me that one could not claim to be part of this movement of Jah people and not read Rodney and his passionate call for slavery reparations.

And Linton Kwesi Johnson’s Reggae fi Radni became a staple though for some it admittedly took them years to understand LKJ’s dub poetry and its reference to one of the Caribbean’s most celebrated pro-Black thinkers. It seemed to follow that episteme of seeking to unlearn what they had been taught at school about everything from Charles Darwin to Christopher Columbus, and reggae seemed to offer the best ideological and theological underpinnings for that re-schooling.

Gabz Fire (real name Gabriel Nyandoro), a popular reggae DJ at Skyz Metro FM, a Bulawayo private radio station, describes the era of sound systems in this city of many cultural experiments and expressions as one that showcased a yearning for not just the spiritually profound ruminations of the chanters and lyricists, but an identity among curious young men growing up in Bulawayo’s poor working class townships just emerging from independence in 1980. “Bulawayo is a reggae town”, Nyandoro says.

“The sound system thrived back then and we even formed reggae bands,” Gabz told me, immediately recalling Peter Tosh’s Johnny B. Good’s aspirations to be a leader of his own reggae band. “I was part of a group called Urban Guerrillas where I was lead chanter. It was an extension of the sound system but this time we wanted to do live jams in front of crowds not just spin vinyls and people loved it,” he said. Phiri says his crew was introduced to live jams by Zig Zag Band who generously let them use their full kit to rehearse original compositions, marking the beginning of the expansion of reggae consciousness from sound systems to live reggae bands. “Second generation Rastas didn’t want to play records at the sound system anymore but wanted to do live shows. From then on, I became a session musician for acts that included Man Soul Jah, Transit Crew and many others,” Phiri said.

What happened then to the stacks of the vinyl records they collected to jam at their sound system sessions? “We have them but they have been overtaken by digitized music formats,” Nyandoro says. The African Teacher says he sold off his vinyls to collectors spread across the globe. Phiri says he lost all his vinyls but maintains a huge catalogue in his digital archives.

Papa Victor has also lost his collection, and like his compadres, keeps a digital catalogue. No one seems to know what became of the giant speakers and turn tables that defined the local sound system. Meanwhile, Nyandoro’s radio reggae show has massive following (the station claims listenership of over a million and growing), a sign that reggae is still alive in the city despite the death of the sound system, he says. Nyandoro’s own oral history is a narrative tableau that blends a rich tapestry of the city’s leanings towards reggae and just how far the country has declined in the intervening years.

“We actually had face-offs at local municipality halls as sound systems and we would have one of our own “toasting” to dub versions of the tracks,” he explained. Nyandoro says in the absence of sound systems, he is using his platform as a radio DJ to discover and nurture young chanters some of whom are taking the movement seriously and schooling themselves in the Rastafari canons.

“It’s all about knowledge, wisdom and over-standing (as opposed to “understanding),” Gabz says explaining the emphasis on reading the Holy Scriptures and other enlightening Rasta writings. The African Teacher says Nyandoro’s presence as a radio communicator is a boon for the spread of Rasta knowledge. “I share with him (Nyandoro) all important dates and events in the Ethiopian calendar that we follow as Rastas and he in turn enlightens the world via his show,” the African Teacher said.

One Rasta took me to his “recording studio” in his township residence where he has a beat making app in his mobile phone and records himself and local kids whom he says he is introducing to reggae consciousness. “There are no sound systems to talk about anymore,” he told me. “That’s why I make my own music now as a way to express myself and keep the culture alive.”

I ask him what he does with the reggae sounds he produces, after all what is music or art if no one else but its creator knows about it. “The plan is to take to it local radio,” he said, but listening to the amateurish recordings, I wondered if the nostalgic Rasta was not setting himself up for ridicule when in fact his enterprise is built on noble intentions. He then showed me a photocopied pamphlet of rules about how a “true Rasta” should live, and it was clear that 21st century interruptions had made it pretty difficult to embrace some of the Rasta exhortations; from an expensive vegetarian and vegan diet, to the absence of platforms of self-expression such as the roving reggae sound systems.

For impresarios such as Gabz Fire, that the sound system is alive and well feeding the creative cauldrons of Harare’s Zimdancehall is a sign that there is no reason why the city of Bulawayo, itself a “reggae town” must fall behind considering the old city’s history with the reggae experience long before Bob Marley chanted about Zimbabwe’s liberation, long before the late great Dennis Wilson gave reggae its mass appeal.

“I have taken occasions or gatherings to play nothing but reggae in the neighbourhoods and you will be surprised by the people’s response. And it is not just the old cats who show appreciation but the youths who one day will push the art and the music further,” he says.

“They know when Gabz Fire rocks a block party, there is nothing else but roots rock reggae,” recalling a time when the once thriving Bulawayo municipality community halls were centres of not just discotheques but cultural expression and offered the reggae fans a platform to “spread the love.” “But so much has changed since then,” he adds.

Today the city’s community halls and youth centres have become wastelands representative of the country’s years of economic decline, the factory-based disposable incomes of yester year young men have been replaced by a feral dog-eat-dog gold rush and violent crime, khaki and rizla paper replaced by cheap liver-melting spirits. “The reggae sound system will never die,” Gabz Fire declares, insisting that long held schedules to take the reggae roadshow back to the people are fermenting in the underground reggae scene, bum-rushed by Covid-19.