NELSON MALDONADO-TORRES

Outline of Ten Theses on Coloniality and Decoloniality*

To fallists and decolonialists in South Africa and everywhere

[T]he black pain of a post-apartheid betrayal of black people is infinitely more painful and dangerous than that of an age when no one had promised any freedom to anyone…. As the Yanks would say, “It is coloniality, stupid!” No need for a doctorate to grasp this. Blackness should be enough.”

Itumeleng Mosala, Former President of AZAPO

“Decolonisation is going to be a harder struggle than anti-apartheid.”

Roshila Nair, UCT, South Africa[1]Private communication on September 23, 2016. Used with the permission of Roshila Nair.

“We must build the archive of Africanism and decoloniality.”

Masixole Mlandu[2]Cited in Cawe 2016.

Colonization and decolonization as well as coloniality and decoloniality are increasingly becoming key terms for movements that challenge the predominant racial, sexist, homo- and trans-phobic conservative, liberal, and neoliberal politics of today. While colonization was supposed to be a matter of the past, more and more movements and independent intellectuals, artists, and activists are identifying the presence of coloniality everywhere. The reason for this is not difficult to ascertain: the globe is still going through the globalization and solidification, even amidst various crisis, of a civilization system that has coloniality as its basis. Therefore, the continued unfolding of Western modernity is also the reinforcement, through crude and vulgar repetitions as well as more or less creative adjustments, of coloniality. This is reflected in contemporary “development” policies, nation-state building practices, widespread forms of policing, surveillance, and profiling, various forms of extractivism, the increasing concentration of resources in the hands of the few, the rampant expression of hate and social phobias, and liberal initiatives of inclusion, among other forms of social, economic, and political control.

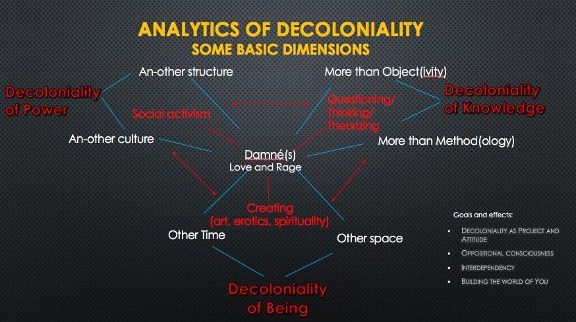

This outline of ten theses is part of an effort to offer an analytics of coloniality and decoloniality with the goal of identifying and clarifying the various layers, moments, and areas involved in the production of coloniality as well as in the consistent opposition to it. In conversation with the first demand of the Movement for Black Lives, the theses pay particular attention to the relationship between coloniality and war. The goal is to better understand the nexus of knowledge, power, and being that sustains an endless war on specific bodies, cultures, knowledges, nature, and peoples, as well as to help evade and oppose multiple forms of decadent responses to decolonization, including narrow views within decolonization movements themselves. In a context where coloniality perpetuates itself through multiple forms of deception and confusion, clarity can become a powerful weapon for decolonization. These theses aim to contribute to this kind of clarity.

Coloniality and decoloniality are concepts used by a wide range of scholars, artists, and social activists in the Americas and increasingly in Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe.[3]Some key references in coloniality and decoloniality are: Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel 2007; Espinosa, Gómez Correal, and Ochoa Muñoz 2014; Lander 2000, 2002; Mignolo 2000 and 2011; Mignolo and Escobar 2010, Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2013, 2015; Pérez 1999; Quijano and Wallerstein 1992; Sandoval 2000; Tlostanova and Mignolo 2012; Walsh 2005; Wynter 2003; and two special issues on the decolonial turn in the online journal Transmodernity 1.2 (2011) and 1.3 (2012). This is part of a decolonial turn in theory, philosophy, and critique, as well as in other areas such as the arts and organizing (Ballestrin 2013; Maldonado-Torres 2006, 2008, 2011a, 2011b, forthcoming; Castro-Gómez and Grosfoguel 2007). My own reflections about these terms owe much to my upbringing in the colony of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the U.S. empire, and my exposure to the racial dynamics and forms of struggle against dehumanization by various ethno-racial groups in the United States (including, African American, Afro-Caribbean, Asian American, Chicana/o, Latina/o, Native American, and Puerto Rican) and outside the United States, particularly in the Caribbean, Latin America, and South Africa.

My own work in efforts to decolonize the university and society have provided insights that I could not have possibly obtained from scholarly engagement with theories of decolonization alone. I have also learned much about theory, action, and the importance of space and time in decolonial projects from a wide arrange of activists. I want to thank student activists and scholars in Atitude Quilombola (Brazil), Minka (Bolivia), Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall (South Africa), and the Third World Liberation Front (USA). If these theses call attention to the importance of this broad body of decolonial work and activism and lead to a substantial engagement with one or more of them, I will consider them successful.

A note with regards to these movements is important here. They are all youth movements or count with youth as an important part of the membership and leadership. There is much talk in liberal societies about youth representing the future. In truth, however, this is considered the case only to the extent that youth seek to continue the same priorities and frameworks of understanding the world as the dominant voices in the current dominant generation. Under these conditions, youth are expected to aspire to bring about a future that is an extension of the present and a future that affirms and redeems the present and the past. In societies with a segregationist or colonial past and with a present of systemic inequalities, youth are expected to play a major role sanctioning the present order and continuing its existence in the future. In this context, as soon as youth—some youth, any youth—have a dissatisfaction with the present, a different perception of the past, and/or different ideas about the future they are perceived as a problem.

Since youth represent the future, their view as a problem causes a battle of temporalities to ensue, but also one of definitions of space and subjectivity, particularly if the youth in question are part of social groups whose lands have been taken and whose forms of subjectivity are vilified. Nothing less than the definition of the very basis of sociality—the self and its relation to the other in time and space—is at stake, and so also the understanding of the conditions on which people should get to explore ideas and share expressions that would help them to make and remake themselves, their space, and their sense of time. This explains why centers of learning have become such important zones of struggle: it is there that a great amount of youth and other students come together to explore those ideas and get to determine how they are going to position themselves in relation to them.

Responses to the youth “menace” typically start with rejection and indifference, but after pressure from the students it can transform into benevolent neglect disguised as “urgent action.” This is reflected in the organization of special conferences and, specially, in the creation of powerless ad hoc committees and task-teams that are meant to take as much time as possible in generating extremely minimal recommendations that hardly anyone will implement and less follow. In the most successful cases, limited measures are implemented, but then contested, sometimes for years, until administrations can successfully undermine them or eliminate them with reference to new financial crises or one-sided reviews and rankings. At times, it is faculty members hired to support the new spaces and projects that turn against them, which should not be surprising given that they were trained in the university and that they work for the university. Indeed, initiatives for diversifying the faculty sometimes turn into surreptitious efforts to find these kind of scholars, who will then “normalize” the new spaces by aligning them with the traditional standards, and who will also play a major role, from the inside, in keeping them as subordinates to other areas or in gradually making them disappear.

Typically, it only suffices for a scholar to legitimize the tendency in universities of prioritizing support for units that are already recognized in established rankings to perform the expected roles from the university establishment. The reason is that the rankings reflect the ossified criteria of excellence that the students and their allies question. Appealing to rankings is not only a form of lazy reason—since the criteria of excellence is defined beforehand—, but also a) another way of eroding the legitimacy of the calls for decolonization, and b) a rationalization for not providing support to the units that advance it. Appealing to rankings is also another way of perpetuating the endless war that the dominant criteria of excellence maintains, but in a sanitized form that does not reveal any subjective preference for some groups and the predominant methods, questions, and issues that they bring to the university to “stay in their place.”

At the same time, there are always at least some scholars and administrators who continue building on the legacy of previous decolonial struggles, forms of leadership, and scholarly work. These are the ones who continuously seek to decolonize the university and who, when the students organize, join the students in that effort. The difficulties that students face in their protests and interventions are, therefore, one part of a multi-layered and intergenerational struggle that includes at least some faculty members and administrators. The faculty members and administrators work within the constraints of their position, but this does not mean that the pressures, bad faith, and hostility that they face is any less lethal than what students find in their day-to-day encounters with epistemic and pedagogical brutality.

As those whose entry in the university represents a crucial step in their plans for a better future, and as those who have to be exposed to the widest range of lectures and services in the institution, students provide a crucial critical assessment of the university. Decolonial student movements also play an irreplaceable role in the process of decolonization and they will continue emerging until the university, if not also society, is decolonized. The result is predictable when they appear. Along with the conferences, panels, and special task forces, security forces are easily introduced on campuses in order to detain metaphysical revolt (of time, space, and subjectivity) on the basis of the liberal credo of protecting property and the individual rights of those who want to continue supporting the dominant institution, episteme, and mode of producing knowledge. What is not considered is the extent to which the movements could be raising issues of principle that cannot be simply addressed by votes and polls. The force that is mobilized against those principles does not dissimulate the brutality: security forces are brought in and violence ensues. Bodies bleed.

Youth are no longer treated as youth, but as criminals. It is convenient to portray them as puppets of infiltrators and of those who oppose government leaders. The priests of the liberal arts and sciences and neoliberal technocrats coincide in their opposition to the movements and reinforce their responses. At the end, the response by the state and private interests follow the notion that violence is doing everyone a favor. The goal is to restore the liberal temporality of slow to no change in the name of order. Decoloniality, instead, is a direct challenge to the temporal, spatial, and subjective axis of the modern/colonial world and its institutions, including the university and the state.

For the longest time, Western universities have been the province of, first, elites, and later, upper class and white middle class sectors. Civil rights and similar kind of struggles led to the formal desegregation of the university, along with various sorts of openings to migrants and non-white subjects. From the perspective of the racial state, though, formal desegregation only meant the possibility of incorporating youth to a project of continued segregation and colonization by their selective admission into the middle classes of the nation-state. Youth are supposed to buy into the promise of admission to the middle class and to value whatever exposure they can get to “civilized” and modern values in the university. In segregationist societies with Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, like South Africa, youth play an important role as they are meant to confirm the pardons given in those processes and to build on the settlements reached by them.

After civil rights and decolonization struggles in the 20th century, liberal societies have continued building on the various lines of dehumanization that were characteristic of their colonial and segregationist older versions by limiting equality to a formality that is most effectively used against groups that demand change, and by considering demands for empowerment and co-participation as calls for tolerance and inclusion. Generally speaking, liberal societies, including universities and their liberal arts and sciences, strive to create a world to the measure of ambiguous and incomplete legal changes that perpetually postpone, if not seek to completely eliminate, any serious accountability, justice, and reparations.

In contrast, students’ actions that include calls for the creation of a Third World College in the late 1960s (USA), to more recent calls for a university of color (the Netherlands) and a “free and decolonised university” (South Africa), among many of such projects, represent the attempt to complete the process of formal desegregation of higher education and to participate in a project of social, economic, and cognitive decolonization. Liberal states should have predicted this: formal desegregation was only the first step in a process that would follow with continued demands for a concrete and real desegregation and for decolonization.

Desegregation is simply incomplete without decolonization.

It is equally predictable that the struggles for a “free and decolonised education” are bound to increase when segregation returns in the guise of fee increases that seek to socialize youth into a reality where the continued patterns of exclusion are justified with reference to the zero-sum game of state costs, a heightened individualism, and neoliberal criteria. That state leaders and leaders of liberal institutions are surprised by these developments simply shows how inadequate the dominant conceptions of social and political dynamics as well as of higher learning and the hegemonic criteria of excellence are. This inadequacy is what students around the globe are trying to address with analyses that take coloniality and decoloniality seriously.

As it is clear on the basis of the case of the colony of Puerto Rico, as well as the living conditions of Black people, Native Americans, and other minoritized subjects in the U.S., South Africa, and elsewhere, liberalism is by no means the opposite of racism, racist state formations, colonialism, or apartheid. Liberalism is rather a political ideology that facilitates a transition from vulgar legal forms of discrimination to in many cases less vulgar but equally or more discriminatory practices and structures.

Liberal institutions in a modern/colonial world aim to advance modernity without realizing that doing so also entails the continuation of coloniality. Universities become centers of command and control, which make them easy to militarize when opposition rises. Many students feel choked and breathless in this context.

Breathlessness is a constant condition in the state of coloniality and perpetual war, but it increases in certain contexts. It is not difficult to identify when breathlessness is caused by a sudden attack or by a very targeted and obvious brutality, like in the tragic case of Eric Garner in the United States (Baker, Goodman, and Mueller 2015). Even in cases like this, though, perpetrators are exonerated. It should not be strange, then, that educators do not even realize the extent to which their students may find themselves breathless as they seat in their classes and listen to their lectures and the comments of their peers, as they go to libraries and find symbols that over-glorify certain bodies and societies and dehumanize others, and as they walk through campus to constantly be reminded of their place by the symbols of white power and control, now presented in liberal forms as representatives of pure excellence. It should not be a surprise if one day students rise and call for this order to fall. As fallists, youth are no longer seen as the future, but as that which must be struck down, imprisoned, and if possible left completely breathless, choked unto death. As a student poet has it:

I stand out in the midst of your power and supremacy degraded by

(Masisi 2016, only abbreviated version here)

your battering and hatred for me because I am.

False lies perpetuated in classrooms and lecture rooms, to make me

feel insignificant and worthless.

Told that my story begins and ends with your supreme nature told

that being dark skinned is

A tyranny

An umbilical cord waiting to be cut and destroyed

Destroyed are the physical ropes and chains you tied my forefathers with.

Still strapped and chained like a slave, like a dog chained to Magogo’s gate.

Mentally enslaved is what it’s called.

Mentally enslaved.

Once again my mother and my father reduced to nothing but labour.

Stripped of my dignity

My integrity gone and nowhere to be seen

HENCE

I CAN NO LONGER BREATHE

The poem provides an insight into the lived experience of a good number of students in universities. Yet, they are supposed to beg for admission and be thankful if they can enter the halls of academia. Then some of them revolt and everyone goes about as if they are too sensitive. Soon enough they are labeled as criminals and thugs. Academics tend to fail them as they are typically more concerned about the state of liberal institutions and about their own professional aspirations and standing than about joining an effort that they will not necessarily lead and for which they will not obtain any positive recognition from the established order or other academics. Security forces are called and students pushed to points where the inevitable mess will be used against them—as if “them,” who are not paid for what they do, “them” who are sacrificing their time and opportunities, “them” who do not have the means of communicating effectively with each other and much less count with the necessary infrastructure to convene and reach collective decisions and orchestrate their actions, yes, as if “them” form a whole that can be accountable in the same way that the government and university leadership should be accountable. Instead, the resulting mess is used as yet another reason to respond to them with brutal force, strengthening coloniality and the tautological validation of the liberal order, liberal values, and the liberal conceptions of knowledge, knowledge production, and excellence. As a consequence, the fresh air that the most intelligent and responsible students are creating in the struggle continues to disappear. They are more used to this than is anticipated, though, as breathlessness – as in closeness to death, as in a condition of permanent torture – is a key dimension of modernity/coloniality and its perpetual war. These theses aim to contribute to the fresh air that is produced in revolt.[4]See Daly 2016 for a discussion of decolonial dimensions of air.

In this context, while some academics start or continue their struggle against colonization in dialogue and collaboration with students, others reappear in their role of critiquing the “irrational” students and sometimes the excessive state forces, as if their direct affiliation with the universities and their lack of direct and actual knowledge of student-led struggles did not challenge their presumed objectivity. The point is not that student movements are perfect. No group or individual is. The point is not that criticism does not have a place inside social movements either. Movements cannot be sustained without the production of critique and the mechanisms to address it. The point is rather that one can only criticize properly when one knows enough about what one is criticizing, and that the only way to know enough about movements that seek decolonization is not by studying them in books or looking at them from the outside.

Too many times some academics state that they agree with the principles of a struggle, but not with the practices of those advancing the struggle. They also feel that their job is to comment on the excesses that they observe. And they tend to think that if they are critical of the state or of the established order, that they need to engage in some equal opportunity criticism and target the movements as well—as if the state and the movements were in a horizontal plane. Everything takes place at the level of knowledge and with the liberal values of supposed distance and neutrality. Since there is hardly any relationship with the movements, other than seeking to lecture them, these academics speak to “civil society,” or just to their other academic readers. Everything is in line with the liberal conception of knowledge that is already inscribed in academia, missing the point that this whole conception is part of the decolonial student movements’ object of critique. The students learn quickly, however, and they start to run away from or confront anyone with these habits. They cannot stand being choked, and less when this is done with the arrogance of presumed liberal detachment and the assumption of a more refined sense of critique, as well as with apparent good consciousness.

Decolonial movements tend to approach ideas and change in ways that do not isolate knowledge from action.

They combine knowledge, practice, and creative expressions, among other areas in their efforts to change the world. For them, colonization and dehumanization demand a holistic movement that involves reaching out to others, communicating, and organizing. A new kind of knowledge and critique are produced as part of that process.

That is, decolonial knowledge production and critique are part of an entirely different paradigm of being, acting, and knowing in the world.

This outline of ten theses will aim to shed more light on this other paradigm and on the conditions for the emergence of decolonial critique. The more complete discussion will appear in the full-fledged version of the theses to appear at a later date. The goal is to contribute to the movement and thereby to increase and help circulate the air, without which movement or real change cannot exist.

The theses and diagrams presented here are introductory, subject to revision, and fundamentally incomplete. They also represent a work in progress. The final version will incorporate more interlocutors and, if successful, offer a better sense of the interrelation between all the elements presented in the theses as well as of their connection to other concepts, practices, and issues that do not appear in the theses yet. Even in their current unfinished shape, however, the theses, the diagrams, and the basic conceptual architectonic can potentially facilitate reflection on coloniality and decoloniality in more comprehensive ways than it is typically done. This is much needed in contexts where these issues are discussed with all the depth that they have while also confronting the dangers that doing so entails, instead of purely or primarily academically. In this sense, the main goal of the theses is to contribute to decolonial intellectual, artistic, and social movements in their analyses.

Finally, the theses are not meant to be closed or conclusive but generative. Part of the reason for this is not only that no set of theses can capture the totality of existing analyses about coloniality, but also that it is simply not possible to encapsulate decoloniality in any singular set of theses. There are simply too many spaces, histories, experiences, knowledge formations, and symbols, to name only a few factors, to pretend to capture final definitions of coloniality and decoloniality. But this does not mean that we cannot aspire to have ever richer and more robust analyses, and that we cannot learn from each other and from the very struggle for decolonization. It does not mean that we cannot breathe together the air that we have left and that, in the closeness of our bodies and minds in struggle, find ways to pass the air that we have to yet more of us and to other generations.

“‘Maman, look, a Negro; I’m scared!’ Scared! Scared!”

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

This thesis addresses the atmosphere that is created and the predominant attitudes that become dominant when anyone raises the question about the meaning and significance of colonialism and decolonization. Addressing colonialism and decolonization as anything more than past episodes or events raises anxieties and fears: anxieties about the legitimacy of the normative citizen-subject and the social, political, and economic order that sustains it, and fears about the very presence and the potential action of those who typically address these topics in this way—that is, the colonized. These kinds of anxiety and fear lead to multiple forms of evasion, to micro-aggressions, and to open aggressive behavior. Anyone who introduces the question about the meaning and significance of colonialism and decolonization most likely faces a decadent and genocidal modern/colonial attitude of indifference, obfuscation, constant evasion, and aggression, typically in the guise of neutral and rational assessments, postracialism, and well-intentioned liberal values. Education, including academic scholarship, national culture, and the media are three areas where this modern/colonial attitude tends to take hold and reproduce itself.

Typical responses to raising the question about the meaning and significance of colonization and decolonization are visceral and aim to relativize the value of the questions as well as to undermine the position of the colonized as a questioner. The bad faith responses are eminently predictable: “This happened in the past and we need to move forward,” “my ancestors were also colonized,” “my parents were poor,” “I am also othered,” “in truth, we are all racists,” “my wife (or husband, or best friend) is one of you,” “I try to join, but they reject me,” “if you keep doing this, the university will be destroyed, the country will perish, or all whites will leave,” and “I am just afraid for what they can do to me and my family.”

The responses also include the assertion that “all lives matter” as a counter to those who declare that “Black lives matter” in a context where Blacks are disproportionally killed and imprisoned by the security forces and the judicial system of the modern state. The abstract universalism of this humanist statement, “all lives matter,” misses the point that, while all lives are supposed to matter—a commonsensical point of departure—, Black lives tend to be taken as a continued exception. This is one among many examples that demonstrates the ways in which liberal abstract universalisms are often used against, rather than in favor, concrete struggles for freedom, equality, and related political rights. Aimé Césaire regarded these responses as decadent (Césaire 2000) and Frantz Fanon as plain idiocy (Fanon 2008).

The goal of these responses is to conceal the relevance of colonization and decolonization and to avoid giving any ground to the protests and questions of the colonized. There is an extraordinarily wide range of responses, created through the long-durée of modern colonialism and racial slavery, collected in cultural symbols, scholarly texts, legal documents, etc., and inscribed in the subjectivities and bodies of normative subjects, that serve as defensive mechanisms in face of these questions. To be sure, the responses are continually asserted even before the critical questions are made. It is a key part of a war that takes place in classrooms, meetings, TV programs, and hallways before any colonized rises in explicit revolt. This is the war in which the citizen-subject and some of the most eloquent agents of the state, typically scholars and the media, do their job aiming to silence the forms of questionings that emerge from the lived experience, creative work, and knowledges of the colonized. This war is constant and its true aim is to make it impossible for the colonized to emerge as a questioner or agent.

If appearing as Black is inherently a violent act, emerging as questioner is taken as a declaration of war against perpetual war.

Modernity/coloniality seeks to conceal its war-like character by not even allowing its status to be named or questioned by those who are at the receiving end of its constant violence.

One important consideration in relation to the idea that decadent and bad faith responses are already inscribed in disciplines, methods, and texts is that individuals only have to rely on what they take as established knowledge in order to justify and hide from themselves the problematic character of their bad faith, decadence, and phobias.[5]The concept of decadence here is informed by Aimé Césaire’s classic statement at the opening of Discourse on Colonialism (Césaire 2000), and by Lewis Gordon’s discussion of “disciplinary decadence” in Gordon 2006. Also relevant in this context is the analysis of bad faith in Gordon 1995a.

That is why individuals, particularly academics in this case, seldom feel racist themselves. As Césaire put it, “In dealing with this subject, the commonest curse is to be the dupe in good faith of a collective hypocrisy that cleverly misrepresents problems, the better to legitimize the hateful solutions provided to them” (32). Colonization, racism and widespread dehumanization are always located in bad faith responses elsewhere: in another society, in one’s society but out of the university or the liberal institutions of the state, in another time, etc.

If those in the structural position of the colonizers feel protected by decadent discourses, for the colonized subject, the effect of this body of work is chilling and paralyzing. As Fanon put it, “I’m bombarded from all sides with hundreds of lines that try to foist themselves on me. A single line, however, would be enough. All it needs is one simple answer and the black question would lose all relevance” (Fanon 2008, xii). And we all know what kind of lines he was alluding to: standard liberal conceptions of the human being of those that plague all the human sciences such as “Striving for a New Humanism. Understanding Mankind. Our Black Brothers. I believe in you, Man. Racial Prejudice. Understanding and Loving.” Fanon refers to these abstract universals as idiocy. In short, anyone who raises the question of what is, fundamentally, colonialism, as Césaire put it, has to be prepared to face a) decadent attitudes that wish to appear as critical, sophisticated or historically informed, b) decadent knowledge that passes as science, c) massive forms of hypocrisy and bad faith, and d) idiocy in the form of decent Western humanism and liberalism.

The reason why the anxiety-producing character of the concepts of colonialism and decolonization as well as the presence of phobias toward the colonized as agents/questioners are the first thesis, is that this thesis calls attention to what represents a performative a priori in the approximation to all the theses. The performative a priori is a demonstration of a decadent modern/colonial attitude which tends to be expressed through multiple forms of evasion and bad faith where the standards of reason constantly change in the effort to make the questions about colonialism and decolonization inert and irrelevant, as well as making the questioner appear as out of place, out of time, and problematic. In that sense, this first thesis is the result of a meta-reflection on the very act of pronouncing any thesis regarding colonization or decolonization. The thesis depicts the terrain of a hypocritical and sleazy form of reason that only allows for a cat and mouse game (Fanon 2008, 99). Victory at this level is simply impossible (99). As Fanon also put it elsewhere: “For the colonized subject, objectivity is always directed against him” (Fanon 2004, 37).

“In the colonies the economic infrastructure is also a superstructure. The cause is effect: You are rich because you are white, you are white because you are rich. This is why a Marxist analysis should always be slightly stretched when it comes to addressing the colonial issue.

Frantz Fanon, Toward the African Revolution

If the first thesis addresses the context and attitudes that one finds when posing the questions of the meaning and significance of colonialism and decolonization, the second provides a basic conceptual differentiation and clarification. Clarity, in this context, challenges the constitutive systematic obfuscation that exists, and the responses that the normative citizen-subject and the institutions and discourses of modernity create when facing the questions of colonialism and decolonization.

While many decolonial figures have used the concepts of colonialism and decolonization to refer to what we call today coloniality and decoloniality, it is also helpful to differentiate between them. The reason is that colonialism and decolonization are for the most part taken as ontic concepts that specifically refer to specific empirical episodes of socio-historical and geopolitical conditions that we refer to as colonization and decolonization. When approached in this way, colonialism and decolonization are usually depicted as past realities or historical episodes that have been superseded by other kind of socio-political and economical regimes. In this way, colonialism and decolonization are locked in the past, located elsewhere, or confined to specific empirical dimensions. They become objects for a subject that is considered to be already beyond the influence of colonialism and the imperative of decolonization. In like manner, from this perspective, those who make the questions about the meaning and significance of colonialism and decolonization inevitably appear as anachronic—as if they exist in a different time and therefore can never be entirely reasonable. In contrast, coloniality and decoloniality refer to the logic, metaphysics, ontology, and matrix of power created by the massive processes of colonization and decolonization.[6]For other definitions of coloniality see, among others, Quijano 1991, 2000; Quijano and Wallerstein 1992, and Mignolo 2000.

Because of the long-time and profound investment of what is usually referred to as Europe or Western civilization in processes of conquest and colonialism, this logic, metaphysics, ontology, and matrix of power is intrinsically tied to what is called “Western civilization” and “Western modernity”.

In fact, the modern West, its hegemonic discourses, and its hegemonic institutions are themselves a product, just like the colonies, of coloniality.

If coloniality refers to a logic, metaphysics, ontology, and a matrix of power that can continue existing after formal independence and desegregation, decoloniality refers to efforts at rehumanizing the world, to breaking hierarchies of difference that dehumanize subjects and communities and that destroy nature, and to the production of counter-discourses, counter-knowledges, counter-creative acts, and counter-practices that seek to dismantle coloniality and to open up multiple other forms of being in the world.[7]For other definitions and uses of decoloniality see, among others, Pérez 1999; Sandoval 2000; Walsh 2005, 2012, 2015.

“Colonialism is the organization of the domination of a nation after military conquest.”

Frantz Fanon, Toward the African Revolution

A third concept that seeks to clarify the meaning and significance of colonialism, in addition to coloniality and decoloniality, is the modern/colonial world (Mignolo 2000). This means that, due to its peculiar genesis and to the practices and categories for understanding that became central in it, Western modernity not only became entangled with the production of coloniality, but was itself constituted by coloniality. Western modernity and coloniality constitute each other: the sense of a particular place, the West, and of the majority of people living in it, that alone are able to break effectively with the past, focus on the present, and go toward the future, distinguishing themselves qualitatively and naturally from all other peoples in the planet and making Europeans and everything that is produced by them superior to everyone else, makes of Europe the modern place that it has considered itself to be for several centuries.

Certainty of European superiority and a constant skepticism towards the full humanity of others took place in the context of the most ambitious expansion of any territories in the history of humanity: an expansion that started in the middle to late 15th century and that still continues into the present.

Europe became modern in the process of conquest and colonial expansion, a process that made colonialism, more than a practice, an organizing logic and a modality of knowledge, power, and being—that is, coloniality.

This does not mean that everything produced by Western modernity is a colonial artifact that cannot but promote colonialism. What it means is that the project of Western modernity as a whole is inherently a colonial one and that many of the ideas and practices that are part of it, including some of the ones that are central to contemporary views of knowledge, good manners, state formation, and education, are entangled with and can easily reproduce coloniality. There is no place for laziness in the analysis of modernity/coloniality. The project of critique, construction and reconstruction is massive. Nothing can be automatically embraced as constructive and empowering; not everything can be rejected as a pure instrument of coloniality. It is possible, however, to aspire to build a different worldview, project of coexistence, and institutions with the collective set of ideas and practices that we have (from everywhere, including Europe, but not only Europe) and that we can create (Gordon and Gordon 2006).

When it comes to conceptions of humanity and to ideals of inter-human contact modernity/coloniality represents a veritable catastrophe (which means a “down-turn”) whereby the world populations started to be divided according to, not merely specific practices or beliefs, but degrees of being human. This catastrophe can be considered metaphysical because it transformed the meaning and relation of basic areas of thinking and being, particularly the self and the other, along with temporality and spatiality, among other key concepts in the basic infrastructure that constitutes our human world. This metaphysical catastrophe is informed by and helped to advance the demographic catastrophes of indigenous genocide in the Americas and the middle passage, as well as racial slavery, among other forms of massacre and systematic dehumanization in the early modern world. Both demographic and metaphysical catastrophe continued and continue in the colonization of Asia, Africa, Australia and all other colonized and peripheralized territories in the modern world-system.

Metaphysical catastrophe is also the basis for nation-state and education models that are continually embraced as “modern” and therefore presumably superior to any others.

In addition to working at the geopolitical and national levels, metaphysical catastrophe also takes place at the level of intersubjective social interactions and in the lived experience of subjects. The first lines of the fifth chapter in Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks offer an example of the colonial and racial dehumanizing turn of metaphysical catastrophe:

“Dirty nigger!” or simply “Look! A Negro!” I came into this world anxious to uncover the meaning of things, my soul desirous to be at the origin of the world, and here I am an object among other objects. Locked in this suffocating reification, I appealed to the Other so that his liberating gaze, gliding over my body suddenly smoothed of rough edges, would give me back the lightness of being I thought I had lost, and taking me out of the world put me back in the world. But just as I get to the other slope I stumble, and the Other fixes me with his gaze, his gestures and attitude, the same way you fix a preparation with a dye. I lose my temper, demand an explanation. . . . Nothing doing. I explode. Here are the fragments put together by another me. (Fanon 2008, 89)

The various layers of metaphysical catastrophe—the geopolitical, the national, the intersubjective, and the subjective—are interrelated and reinforce each other. As the Chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldúa put it in her theoretico-poetic language:

1,950 mile-long open wound

dividing a pueblo, a culture

running down the length of my body,

staking fence rods in my flesh,

splits me splits me

me raja me raja

(Anzaldúa 2007, 24)

The border between Mexico and the United States is presented as a wound that divides a people, a culture, and an embodied self.

Metaphysical catastrophe changes the meaning and function of the basic parameters of geopolitical, national, as well as subjective and inter-subjective dynamics to the extent that it creates a world to the measure of dehumanization. It turns a potential world of human relations into one of permanent forms of conquest, colonialism, and war. I have referred to this elsewhere as the modern/colonial paradigm of war (Maldonado-Torres 2008). This means that the extraordinary behavior that takes place in war becomes normal and ordinary in colonial contexts and wherever there are colonial subjects. This paradigm can be in effect in actual wars and genocidal practices as well as in democratic societies.

That metaphysical catastrophe is linked to Western civilization and war and that it leads to the naturalization of war explains why colonial conditions in modernity resemble perpetual war zones where extreme violence and constant low-level violence are continually directed to colonized populations and those who are identified as their descendants. This helps explain the significance of the Movement for Black Lives calling for an “end to the war on Black people,” a war that is waged constantly on certain bodies and on everything closely associated with them through a myriad of practices that include profiling, imprisonment, rape, low wages, difficult or no access to adequate housing and health care services, never ending condescension, epistemological and pedagogical disciplining, and multiple other forms of putting Black people “in their place.”

Metaphysical catastrophe creates a profound scission in the concept of humanity, serving as foundation for a system that will no longer be structured in terms of intra-human differences justified by tradition and religion only, but gradually also by scientific and secular accounts of differences between the human proper and the sub-human. In the process of the expansion of the West since the 15th century to our days, metaphysical catastrophe has increasingly divided what used to be conceived in terms of the Christian oecumene, into zones of being human and not being human or not being human enough. The advancement of modern conquest and colonialism involved not only the creation of a geopolitical division based on metaphysical catastrophe, but also the imposition of ideas of social organization and structures. In this context, the plurality of conceptions of community and human difference is violently flattened down, effectively although in many cases not entirely with complete success, resulting in the creation of a global community with similar priorities, perceptions, and desires: what Sylvia Wynter refers to as ethnoclass Man (Wynter 2003).

Metaphysical catastrophe can therefore be understood as the production of zones of being human and zones of not-being human or not being human enough.

Living in the zone of being human means finding oneself, others, and the institutions of one’s society affirming one’s status as a full human being with a broad range of potentials and possibilities even in precarious conditions of poverty. Living in the zone of sub-humanity means, not only that one is not meant to have easy access to basic means of existence, but also that it is normal for everything and everyone, including oneself, to questions one’s humanity. One can refer to this as a fundamentally misanthropic skeptical attitude. Misanthropic skepticism is a characteristic questioning attitude of modernity/coloniality, whereby the humanity of large part of humanity is questioned. Misanthropic skepticism is the quintessential attitude of modernity/coloniality and one that not only justifies but calls for the elimination of populations, slavery, and permanent war (Maldonado-Torres 2007). The zone of subhumanity is the zone of endless war.

Another way to understand the catastrophic creation of zones of being human and zones of not-being human is in relation to existential ontology. If, following Jean-Paul Sartre, one defines “being” as fullness and “non-being” as transcendence from being or the indetermination of freedom, then metaphysical catastrophe creates a zone below the zones of being and non-being. In the zone of being human, human existence is driven by the dialectic between the embodiment and sense of identity of the self on the one hand, and consciousness and freedom on the other. For Sartre, human beings are “condemned to be free,” in the sense that they cannot escape the indetermination and responsibility of freedom (Sartre 2007, 29). In this context, the perceptions that others have of oneself are often taken as confirmations of or challenges to one’s own sense of who one is. The social arena is the space of these encounters where subjects meet others. For a subject who is trying to have others confirm her or his own sense of being, sociality can feel like hell. For them, as Sartre put it in his play No Exit, “hell is—other people” (Sartre 1989, 46).

If for subjects in bad faith, freedom and sociality appear as forms of being in hell or condemned, metaphysical catastrophe creates a veritable hell below any such hell of authenticity or inauthenticity.[8]See also Lewis Gordon 2005, 2007, and 2015 for reflections on the meaning of the mythopoetics of hell and the zone of nonbeing in Fanon’s work. Here I am combining insights from Gordon’s Fanonian decolonial phenomenology, Latin American, Chicana/o, Latina/o, and Caribbean coloniality and decoloniality theorizing in addition to constructing new categories, including efforts at fresh readings of Fanon, at the intersections of these and other bodies of knowledge.

This is a hell where “torture-chambers, the fire and brimstone, the ‘burning marl’” are less “old wives’ tales” or mythical images of damnation (Sartre 1989, 46), and more one where war is endless and perpetual. If the “black man cannot take advantage of this descent into a veritable hell,” writes Fanon, it is because he is already living in a hell where his very existence, and not his authenticity, is at stake (see also Gordon 2005). This means that the project of decolonization is one that strives for something more than authenticity: it is empowerment, liberation, decoloniality, and a war against metaphysical catastrophe and permanent war.

In the hellish existence of modernity/coloniality, the imposing other for the Black subject and the colonized is not so much an Other, but a vicious and brutal Master.

In a similar vein, the Black and colonized do not appear to this Master as others, but as perpetual slaves (Fanon 2008). This is a hell where one is condemned not because of being free or because one has to contend with the image that multiple others have of oneself, but because one is always already trying to become someone else. For a black person, this means that one is always trying to kill the black in oneself. The war therefore is within and without. As the very title of Black Skin, White Masks suggests, the modality of existence in the hell of coloniality is that of self-erasure: blackness must disappear or at least be covered-over by whiteness. Blackness must not have anything substantially, neither land or much time to live, nor goods and resources, and not even the possibility to generate self-esteem.

Value, for Blacks, is supposed to be elsewhere and forever postponed.

In this context, the meaning of death is overdetermined and the anticipation of one’s death as black is not meant to provoke anxiety, potentially leading to authenticity, but rather to a sense of accomplishment, of having finally killed the black in oneself.

That is, one’s death as black is not the end of oneself, but the precondition of entering the zone of being human and the world of modern salvation.

This is different for those in the zone of being human who are not only accepted but become the norm of a social order. For them, their finitude reveals their innermost possibilities within the zone of being human, meaning that authenticity does not lead to decoloniality. For them also, death is only the possibility of passing their knowledge and wealth to yet new generations of others who continue building the world of coloniality. Where true anxiety over death emerges for the normative subjects of the zone of being human (e.g., the white) is when they consider, not their individual death, but the complete de-legitimation and the end of their world. When considering finitude from that perspective—the end of their world— what the normative subject experiences, more than just anxiety, is terrible fear of the ones whose very presence put in question the legitimacy of their world. From here that normative subjects (particularly whites) experience anxiety in the face of discussions about colonialism and decolonization and that they have an innate fear of the colonized as both non-human and as a perceived threat to the order of modernity/coloniality. This third thesis, then, helps us to better understand the first thesis: the anxiety and fear of normative subjects and of all of those who assume some degree of authority in the modern/colonial world toward the question about the meaning and significance of colonialism and decolonization is the standard response of subjects who belong to or believe that they have been adopted into the zone of being human. Driven by anxiety and fear, “objectivity,” along with other presumably lofty ideals such as excellence, are used to keep or increase the boundaries between those who claim to be in the zone of being human and those condemned to the zone of dehumanization. This is all part of the never ending warfare over colonized bodies and minds for them to keep their assigned status under modernity/coloniality.

In short, metaphysical catastrophe creates a context where the colonized subject is at war with itself, trying to kill any trace of the black, native, and colonized within and without, while also being at war with each other to achieve the same purpose. All the while, the colonized also face another war in the form of a constant evasion and multiple agressions by those in the zone of humanity who consider them as sub-humans. Then there is the established discourse and institutions that locate the colonized in a precarious place of existence: the ghettoization of space, prisons, environmental racism, death by police, recolonization through education, etc. These are four modalities of war that mark the day to day life of the colonized.

Metaphysical catastrophe, the naturalization of war, and the productions of the zones of being human and not-being-human—not ontological difference, but sub-ontological or colonial ontological difference (Maldonado-Torres 2007)—can contribute to the theorization of various forms of coloniality, such as the coloniality of nature, the coloniality of language, the coloniality of vision, and the coloniality of gender. Given the central role of gender in wars (see Goldstein 2001; Sharoni, Welland, Steiner, and Pedersen 2016), and, particularly in European conquests and colonialism, as Pumla Gqola has noted (Ggola 2015), it is important to make explicit at least some basic implications of metaphysical catastrophe and the naturalization of war to the way in which gender difference is understood in modernity/coloniality.

With regards to gender, this analysis suggests that the modern/Western male and female binary is informed and informs the division between the subject as freedom and the subject as body that was discussed earlier. Masculinity is typically conceived as the seat of the highest form of self-determination and freedom and to some extent also in terms of the most refined and able body. If the male is rational and active, the female is seen as irrational or emotional and passive. In the modern/colonial world, this activity and this passivity is understood against the background of another reality where subjects seem to share more characteristics with non-human animals than with humanity proper (Lugones 2007, 2010). This does not mean that femininity has not been identified or continues to be identified with animality in some ways, but that coloniality naturalizes this condition and makes it irrefutable, systematic, and permanent for all colonized subjects in ways that justify a perpetual war. Colonized men and women therefore appear as natural and permanent enemies who are always threatening and suspicious. The response is consistent with actions of war, as we will see more carefully in the next thesis: people are treated as enemy combatants whose bodies are annihilated, rape, and/or tortured. Lands and resources are taken away. Since war is anchored in the catastrophic order of things and is perpetual, neither land, resources, or any sense of dignity are meant to be given back. Quite the contrary, the colonized live as if they always have to pay reparations to the colonizers for their loses and efforts during conquest and the construction of the new society. The colonized have to continually pay to the colonizer for allowing them to continue existing, which is why any demand from the colonized is considered to be a call for an undeserved “entitlement”, if not a declaration of war.

The bodies of the colonized, subjected to total and perpetual war, have different meanings than the bodies of those who inhabit the zone of being-human. As much as femininity is conceived in terms of passivity and embodiment, femininity is generally considered to be an abused but also protected zone that limits the extend and degree of violence towards those who are seen as feminine. Therefore, a black woman is, by definition, never considered to be feminine enough, or is outside of the standard norms of the feminine (see Davis 1983; Spillers 1987), which means that whatever safeguards come with being recognized as female do not extend to black women. Something similar happens with black men. This is part of the results of metaphysical catastrophe and dehumanization. The categories of male and female in Western modernity are already overdetermined by a chain of significations that are created with coloniality as a background. This means that colonized males and females would be ill advised by trying to become masculine or feminine in the way that these terms have been already defined. The challenge is to create new meanings, new concepts, and new forms of being human.

One challenge for this imperative of creation or re-creation is that while there is space for a degree of movement and transformation in the relation between body and consciousness, and that of one’s first person perspective and the perspective that others have of us, as well as between masculinity and femininity in the modern/colonial world, the relation between the zone of humanity and the zone of sub-humanity, and therefore the relationship between the colonized and the colonizer is fundamentally non-dialectical. This means that the line between being human and not being human enough is meant to be solid, even if some subjects or groups are located in different positions with regards to it and even though some groups are able to change positions after a certain time. What persists is the line of differentiation itself, as well as its logic and organizing framework, which tends to be anchored on specific peoples and bodies. For example, when the Movement for Black Lives calls for an end to the war on Black people the movement makes evident that Black people have remained as one of the most consistent references to maintain the line of differentiation between the human and the sub-human. The word “nigger,” in fact, is perhaps the most, or one of the most, direct terms in English vocabulary to make anyone appear as belonging to the hell of sub-humanity (Wynter 2003). As Gordon notes “‘Nigger’ points to the fatalism of the ultimate Other. ‘Niggerness’ is the lowest denominator; it robs itself of most human possibilities—freedom, value, self-awareness” (1995, 105). The term has an immediate metaphysical violence. It tries to place a human in a zone where s/he/they is susceptible to denigration and a constant target of the violent dimensions of perpetual war.

In summary, metaphysical catastrophe and perpetual war shape time, space, subjectivity, as well as many other areas including the conditions for producing knowledge, the criteria for truth and validity, aesthetics and the criteria of aesthetic value, morals, and politics, etc., including the possibilities of change. Metaphysical catastrophe creates new coordinates for the unfolding of being and nonbeing and changes the conditions for any kind of dialectical change, making such change a perpetual postponement and a formal impossibility with regards to the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized.

“Colonialism cannot be understood without the possibility of torturing, of violating, or of massacring. Torture is an expression and a means of the occupant-occupied relationship.”

Frantz Fanon, Toward the African Revolution

“The Algerian woman is at the heart of the combat. Arrested, tortured, raped, shot down, she testifies to the violence of the occupier and to his inhumanity.”

Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism

“There is a connection between rape culture, the manufacture of female fear and violent masculinities…. Hypermasculinity goes hand in hand with violent masculinities, misogyny and war talk.”

Pumla Gqola, Rape: A South African Nightmare

Extermination, expropriation, domination, exploitation, early death and conditions that are worse than death such as torture and rape are all predominant in warring contexts. In modernity/coloniality, all of these actions take place perennially, not as a response to specific conflicts, but as ways to be in accordance to the perceived order of nature and the world. In this context, a presumably extraordinary practice such as torture becomes a “way of life” and “a fundamental necessity of the colonial world” (Fanon 1988, 66).

Like colonialism, coloniality involves the expropriation of land and resources. Unlike traditional colonialism in which expropriation primarily takes place through direct forms of conquest of one group over another, under modernity/coloniality expropriation happens also through the logic of the market and of modern nation-states. This leads to a situation of colonies where their native and colonized subjects continue experiencing vast forms of dispossession even after independence. In this process land and resources are taken away, but so also are the very possibilities for the colonized and dehumanized self of emerging as embodied subjects that can properly give, receive, think, create, and act.

The colonized are meant to be bodies without land, people without resources, and subjects without the capacity for autonomy and self-determination whose constant desire is to be other than themselves.

The bodies of the colonized and dehumanized are exploited for labor in ways that remain in a lower status than the normative subjects in the metropolitan proletariat. Time, for the colonized, is less the time of production, and more the time of surveillance and of waiting for denigration, violation, and murder to take place. Life is lived as in a torture chamber making life acquire the overwhelming feeling of it being worse than death. Similarly, being colonized means that life is lived waiting for the permanent possibility of one’s body to be violated by another. This is particularly devastating for colonized women because in the modern/colonial world masculinity is defined as power over women, meaning that anyone who wishes to claim masculinity is expected to perform violence over female bodies. Colonized women are particularly vulnerable as they are not protected by the codes of femininity in the first place, codes that allow for violence but that also extends some protections. Therefore, violence towards the bodies of colonized women can be seen as an affirmation of masculinity that does not carry major consequences. This assertion of violence, however, leaves a hole, as it were, since power over colonized women does not indicate any substantial amount of real power in a system where they do not even properly represent the idea of the feminine. Therefore, there does not have to be an ultimate purpose for violence to be exercised over the black, native, and colonized women. The system marks them as available for immediate sexual gratification. These dynamics extend and acquire various other subtleties when one considers trans bodies and homosexuality.

With respect to colonized men, including Black, Native, and other men that in a particular context are perceived as colonized or substantially inferior, they are also marked in ways that make their bodies accessible for sexual pleasure, but male supremacy, heteronormativity, and the oversexualization of the feminine makes women particularly susceptible to this reality. In the world of perpetual war, colonized males are in many contexts particularly susceptible to being conceived as enemy combatants who are a threat to the lives and power of white males and to the “honor” of white women. Therefore, the best approach is to kill them, imprison them, and profile them, all tactics of war. Female bodies of color will also be killed, imprisoned and profiled, as they also threaten the integrity of the modern/colonial world and cannot but appear as violent as well. Therefore, the modern/colonial world demands a complex, systematic, and enduring exercise from the colonized to perform non-threatening behavior. They must appear as impeccably professional, rational, and nationalistic, among other features that reduce the anxiety and fear that their constitution as colonized creates in this context. Anything else than that can easily make them appear as thugs, militants, “whores,” etc. All of this is also part of the day to day reality of endless or perpetual war.

“And since I have been asked to speak about colonization and civilization, let us go straight to the principal lie that is the source of all the others. Colonization and civilization?”

Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism

Worldviews cannot be sustained by virtue of power alone. Various forms of agreement and consent need to be part of it. Basic ideas about the meaning of basic concepts and the quality of lived experience, about what constitutes valid knowledge or points of view, and about what represents political and economic order are areas that help define how things are conceived and accepted in any given worldview. Human identity and activity (subjectivity) also produce and unfold within contexts that have precise workings of power, notions of being, and conceptions of knowledge. The coloniality of knowledge, being, and power is informed, if not constituted, by metaphysical catastrophe, by the naturalization of conquest and war, and by the various modalities of human difference that unfold in the zones of being and not-being human.[9]The coloniality of power, being, and knowledge are concepts that emerged in what Arturo Escobar called the “Latin American modernity/coloniality research program” (Escobar 2010). Counting with several participants from the Caribbean and the United States, the “research program” was not precisely Latin Americanist, but Escobar’s article is a good introduction to the ideas that circulated in this network between the 1990’s and 2010. For early elaborations of the notion of coloniality and coloniality of power see Quijano 1991; Quijano and Wallerstein 1992; and Quijano 2000. Walter Mignolo identifies the extension of the “coloniality of power (economic and political)” to the “coloniality of knowledge and coloniality of being (gender, sexuality, subjectivity, and knowledge)” to three of four years prior to 2007 (Mignolo 2007).

Each of these major dimensions of what constitutes a worldview (knowledge, power, and conceptions and forms of being) has at least three basic components and each of them includes reference to the embodied subject. For the purposes of this reflection, I will approach what we usually consider knowledge as consisting of at least three major elements or coordinates: subject (and subjectivity), object (and objectivity), and method (and methodology). This does not mean that there might be other conceptions of knowledge that do not admit of such a clear differentiation between these terms or that include other terms. The idea is rather that subject, object, and method are key terms in the modern/colonial conception of knowledge and that we have to understand this structure in order to critique it and take whatever is of worth for a decolonial conception of knowledge and understanding.

In like manner, I will approach power as having three major elements that constitutes it and that it helps to constitute: structure, culture, and subject.

This understanding of power is largely inspired by Fanon’s concept of sociogeny which calls attention to the nexus of the social structure and culture, on the one hand, and the subjective realm, on the other. Fanon believes that any effective disalienation has to take place in the subjective and the objective levels. In turn, I approach being as having the following three major elements or coordinates: time, space, and subjectivity. From a very concrete approach, everything that exists does so in time and space. Being, in the concrete sense of the terms, means existing in time and space. The representation of any being in such time and space, in turn, involves subjectivity. In summary, we have the following basic scheme to approach modernity/coloniality:

Knowledge: Subject, Object, Method

Being: Time, Space, Subjectivity

Power: Structure, Culture, Subject

One important point to note is that there is one element that is part of each trio of terms: subjectivity. I am also following Fanon here. Even though Fanon was a psychiatrist, for him the subject was not a psyche that could be medicated in the effort to make it more attuned with the “civilized” world. Rather, for him, the subject was a constituted and constituting basis that stands at the crux of being, power, and knowledge. That is why Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks is not ordinary psychiatric or psychological study. In it, Fanon offers crucial elements to decolonize, not only these specific areas, but the entire range of the human sciences, subjectivity, and society. Fanon saw the subject as both the product and a generator of the social structure, culture, and the entire worldview of a time. Fanon approaches the subject as not only a key element in the constitution of being, power, and knowledge, but also as perhaps the most direct and central element that connects them to each other. I propose that for Fanon, therefore, and for my approach here, the subject is a field of struggle and a site that must be controlled and dominated for the coherence of a given worldview and order to continue undisturbed. We can represent these basic points in the following way:

Modernity/coloniality is a peculiar construction of knowledge, power and being that divides the worlds into zones of being and not-being human and that makes war endless and perpetual. Following Fanon, then, the subject can be conceived as a point of entry into the critical examination of modern/colonial conceptions of being, power, and knowledge, which together help create the basic infrastructure of the modern/colonial world. Now, Fanon does not focus on just any subject or on the subject in total abstraction. In Black Skin, White Masks Fanon focuses on the colonized black subject. Later, in The Wretched of the Earth [Les damnés de la terre], he refers to subject in a similar structural and subjective position as the damnés, a word that had circulated before to refer mainly to the world proletariat. In Fanon, the concept of damnés acquires new meanings. To start, from a Fanonian point of view, the damné is the subject who appears at the crux of the coloniality of power, the coloniality of knowledge, and the coloniality of being. The coloniality of power, knowledge, and being refer to how power, knowledge, and being, along with its constituent element, function in the zone of sub-humanity. The coloniality of power, knowledge, and being is also, generally and abstractly speaking, what creates the line between the human and non-human, between the world where perpetual peace is considered a possibility and the world that is defined as perpetual or endless war. The coloniality of power, knowledge, and being also refers to how time, space, culture, structure, method and conceptions of subjectivity and objectivity transform through metaphysical catastrophe. Modernity/coloniality is, in fact, the catastrophic transformation of whatever we can consider as human space, time, structure, culture, subjectivity, objectivity, and methodology, into dehumanizing coordinates or foundations that serve to perpetuate the inferiority of some and the superiority of others. It is an epochal instantiation of the master/slave dialectic, with the exception that the structure is meant not to be dialectical. That is, in the modern/colonial world, the colonized are meant to perpetually be condemned to the zone of damnation or hell. And so, following Fanon, the subject that is constituted by the coloniality of knowledge, power, and being as the subject against other forms of subjectivity will be defined, can be described as the damné or condemned. This is an embodied subject who is pinned down in hell in various ways including by virtue of how it appears.

The very surface of this body, the skin, can serve as an immediate identifier.

The more a subject can be thus identified, the more difficult it is for that subject to live other than in a constant hell. Black Skin, White Masks focuses on the black subject, an embodied subject who simultaneously lives in various layers of hell.

Here is a possible way to conceive of this basic analytic of modernity/colonality:

The damnés are the subjects that are located out of human space and time, which means, for instance, that they are discovered along with their land rather than having the potential to discover anything or even to represent an impediment to take over their territory. The damnés cannot assume the position of producers of knowledge and are said to lack any objectivity. Likewise, the damnés are represented in ways that make them reject themselves and, while kept below the usual dynamics of accumulation and exploitation, can only aspire to climb in the power structure by forms of assimilation that are never entirely successful. From here the tragic dimension of this structure (see also Gordon 1995b, 1997). The coloniality of power, being, and knowledge, aims to keep the damnés in their place, fixable.

There is another meaning of the concept of damné, and one which opens a path towards the notion of decoloniality. As I have developed elsewhere (Maldonado-Torres 2008), etymologically speaking, the French word damnés is related to donner, which means to give. The damnés are literally the ones who cannot give because what she or he has has been taken from them. This means that coloniality erodes the basis of giving and receiving, which is intersubjectivity.

Giving and receiving are central in Black Skin, White Masks and they form a central part of Fanon’s understanding of the human being. That is why, to a large extent, Black Skin is a text about the primacy of love and understanding. These are both relations that for Fanon are based on the primacy of body-to-body intersubjective contact: eros and other forms of love as well as communication or understanding in terms of language and knowledge. This is why the first four chapters of Black Skin focus on love (chapters 2-3) and language and knowledge (chapters 1 and 4). These chapters seek to demonstrate the distortions of love and communication in the zone of damnation or not-being human. In it, subjects are condemned to live in a world where love and understanding are systematically distorted. From being nodes of love and understanding, subjects become entrapped in a kind of narcissism that partly generates and/or is partly generated by suicidal and genocidal tendencies. This is key to understanding the catastrophic character of modernity/coloniality: the basic coordinates of what for Fanon defines humanity are fundamentally distorted to the point of turning a human being into a promoter of extreme forms of narcissisms, superiority, and self-hate. The centrality of love and understanding give way to the naturalization of death, rape, and torture in conditions of endless or perpetual war.

From this point of view, more than a treatise on psychiatry, Black Skin is a foundational work in the area of philosophical anthropology that offers an entire new definition of philosophy (see also Gordon 2005b; 2015). That is, while philosophy is traditionally conceived as the love of wisdom, for Fanon, or rather through Fanon, we can conceive of philosophy as the intersubjective modality of love and understanding. Philosophy is therefore not simply a particular form of questioning or production of knowledge that characterizes the work of some people called philosophers. Rather, philosophy can be conceived as a name for the basic coordinates of human subjectivity: the modality of intersubjective love and understanding.

Fanon has a conception of the subject that is directly at odds with the Hobbesean notion that in the state of nature human beings are in a war of all against all (Hobbes 1982 [1651]). Fanon refused to hypothesize about the state of nature, but rather, arguing for sociogeny, started from modernity and the fact of coloniality. Coloniality is a veritable war, and an endless or perpetual one at that, though not a war of all against all exactly. Coloniality and its perpetual war represent the state of humanity, not before the emergence of a Sovereign, but more exactly after the global expansion of modernity/coloniality. In this form of warfare, all bodies are not the same and it is not simply strength that rules. In modernity/coloniality, human beings are not so much wolves, as supremely socialized subjects who target specific subjects and modes of being for elimination, even themselves if they carry the marks of damnation. In this sense, the endless war of coloniality is both, more discriminating and also more lethal than a generalized war in which all human beings act like wolves. Modern gendered and ethno-class Man creates and preserves borders of differentiation that aim to distinguish bodies, spaces, knowledges, and forms of being targeted for elimination, rape, and torture, from others that are meant to be protected from such actions.

In its most basic form, metaphysical catastrophe refers to transmutation of the human, from an intersubjectively constituted node of love and understanding, to an agent of perpetual or endless war. In modernity/coloniality, embodied subjects emerge, not by the interpellation of an-other, but by the co-constitution of regimes of knowledge, power, and being that aim to make of this subject an agent of coloniality. The subject is meant to support and help refine these regimes from generation to generation, making war endless.

Ending perpetual war thus necessitates the formation of embodied subjectivities that resign from the process of searching for recognition and validation in the modern/colonial world. Decolonization is not so much about obtaining recognition from the normative subjects and structures, but about challenging the terms in which humanity is defined and recognition takes place. This necessitates the formation of new practices and ways of thinking, as well as a new philosophy, understood decolonially, not so much as a specific discipline or way of thinking, but as the opposition to coloniality and as the affirmation of forms of love and understanding that promote open and embodied human interrelationality. This is why decoloniality can be understood as first philosophy: it is the effort to restore love and understanding. This includes the critique of coloniality, on the one hand, and the affirmation of all practices and knowledges that promote love and understanding, on the other. Without a subject who can love and communicate with others, and without forms of wisdom, knowledge, and objectivity that cannot so easily lend itself to the anxieties, fears, and forms of bad faith of cognitive subjects, there cannot be any true philosophy.

It is often said that philosophy starts with a change of attitude. In a context defined by modernity/coloniality, the emergence of philosophy depends on the formation of a decolonial attitude. The decolonial attitude is part of a decolonial turn away from the “down turn” of metaphysical catastrophe. It is a turn to the metaphysical and material restoration of the human and the human world, including nature. The first philosophers are therefore those who, oriented by a decolonial attitude, commit to creating the conditions for love and understanding. These are decolonial activists, artists, theorists and intellectuals, as well as community leaders and everyone committed to undermine coloniality and to promote decoloniality.

“From this cell of history this mute grave we birth our rage.”

Janice Marikitani, “Prisons of Silence”