a learned man

came to our village

to tell us

in every step

every motion,

and gesture

we do in the very act of living

we give birth

to a body of knowledge

& a corresponding tongue

articulating a specific

way of living.

at

the

same

time

he

presented

our

world

as

he

sees

it

in

his

eyes

portraying an image

of ourselves,

that is his

view

of the world…

mphutlane wa bofelo

The poem above depicts a patronising scholarship and research paradigm in which the voice of the scholar throttles the tongues of the common people and portrays them as mere subjects and objects of research, even as it pays lip service to an appreciation of their insights.

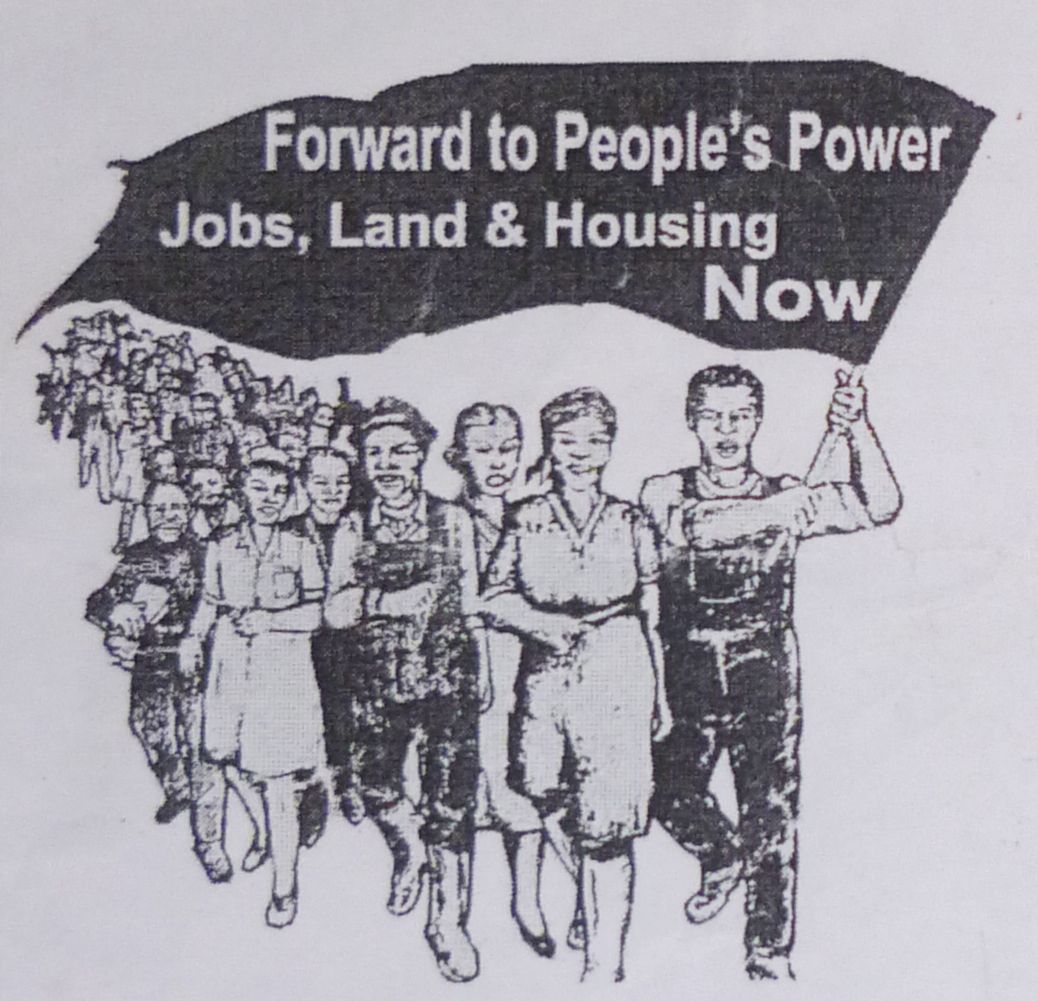

On the contrary, a progressive, critical, and engaged scholarship and radical academic activism seeks to amplify the voices, experiences, insights, and perspectives of the people and to portray the people as agents of history rather than mere subjects and objects.

In Amakomiti: Grassroots Democracy in South Africa’s Shack Settlements, Trevor Ngwane trod the road of a critical and engaged scholarship – or what Giroux would call “a borderless pedagogy”, in unmuting the voices and experiences of the residents of South Africa’s shack settlements and unveiling their agency. Amakomiti is more than an ethnographic study and narrative that enlists an appreciative inquiry paradigm that entails a form of social engagement in which questions and dialogue are used to unearth, reveal, and expose existing strengths and opportunities within a community and to recognize what works well and analyse why and what is required to enhance it. It is a journey of rediscovery and reassurance in which the writer\researcher who unequivocally express his admiration for the workers and his fondness to talk to people – and is himself a seasoned activist in grassroots-based organizing and movement-building – walks, talks, and learns with and from the people who are at the forefront of the recovery, resurgence, and revitalization of a longstanding tradition of self-organization among the working-class and underclasses.

Like Saul Alinsky’s outsider-insider professional agitator, Trevor Ngwane starts from the premise that there is no unorganised or leaderless community. His entry point is that all communities have some or other form of organization or leadership and have their own ways and language of expressing their agency. Accordingly, in Graaff-Reinet, in the Great Karoo, Ngwane starts his entry and voyage into the community, as a rover, asking for direction from the locals about where the local committee is. His voyage of rediscovery begins with a direction-seeking question: “Ngingalitholaphi ikomiti lalendawo? (Where can I find this place’s committee?).

The acknowledgement of the ordinary man\woman on the street, rather than the usual gatekeeper, as a repository of knowledge about the community elicits not only a confirmation about the existence of a committee in the settlement. It also prompts voluntary sharing of information about the place’s economics and climate:

“Living here is terrible; there are no jobs. And it can be hot.”

In this way, Ngwane finds an informant and a tour-guide\community-guide in one person. While moving from the position of conviction about the existence of community agency\institution in one form another, Ngwane makes no presumptions about the organizational forms nor is he romantic about local experiences and local experiments of self-organization. Out of 46 settlements that he visited, Ngwane found only one without a committee. The rest had committees in one shape or another and consisiting of all types of characters: the young and the old, men and women, employed and unemployed, literate and illiterate, sober and drunk people.

Throughout the journey, Ngwane is met with the reality that the types of organisations (in this case, committees) and leadership existing in each shack settlement may not be ones that rhyme with one’s own intellectual, ideological, and political orientation nor with idealised or conventional notions of individual and collective agency, organizations, and leadership. Instead what are to be found are organisations and leadership that rhyme organically in response to the intricate and complex workings and dynamics of the specific different and unique communities.

Ngwane expresses no shock at the existence of one-person committees, nor does he hide the existence of autocrats and landlords within shack settlements’ committees. He does not allow the enigma, charisma and controversy associated with some of the legendary figures and “big-men” of Amakomiti to strangle his appreciation of the “organizing skills, political acumen and ideological underpinning involved in leading the shack-dwellers movement.”

Importantly, Ngwane does not paint an idyllic or utopian image of the self-organization in the shack settlements. He recognizes possibilities and points of infiltration and instances where the committees are either abused as conduits of the interests of all sorts of opportunists and charlatans or are subdued by the organizational and resource capacity and patronage of the ruling party. He is aware of the squeeze of state terror and police brutality on political and organizational action in the shack settlements. Moreover, Ngwane acknowledges the limitations that the conditions of squalor, lack, and absolute deprivation, systemic and structural violence, unemployment, and poverty places on the humane agenda of “bringing the best out of human beings.”

Ngwane also emphasizes the dynamic interaction of organization and spontaneity in the phenomenon of Amakomiti as well as the existence of both centralization and decentralization in the workings of different committees in the shack settlement. This is not a book of romance. It is a treatise on the barriers and possibilities of building democracy from below through innovative and diverse forms of self-organization and alternative forms of organizations informed by the desperate struggles of the damned of the world to reanimate and rehumanise themselves under de-humanizing and brutalizing conditions.

As much as the book provide examples of hope such as the political culture of open debate, participatory democracy, and respect for the collective voice of the so-called common people inculcated by Thembelihle Crisis Committee (TCC), it points out weaknesses and excesses and the hard and critical thought and action that it will require to take the radical optimism represented by Amakomiti beyond hope.

Publisher: Jacana Media, Year of publication: 2021