FRANK MEINTJIES

James Matthews: dissident writer

The diminutive writer, James Matthews, is known as the dissident poet. Although he refers to himself by this term, he is so much more. Since his voice spanned poetry, journalism and short stories, the term ‘dissident writer’ captures this greater breadth.

On 17 June 2022, James Matthews was honoured by the Department of Sports Arts and Culture (DSAC) under the Van Toeka Af programme at a special recognition event in Cape Town. This acceptance by the establishment is ironic given that Matthews has – for so much of his life – been on the outside, banging on doors, lobbing verbal broadsides and sparring with the establishment.

Much more will be written about Matthews and his life, one which has inspired so many over the decades. This piece, however, focuses on his short story writing.

James’ impulse towards writing came from within. His first piece of writing was done as schoolwork. Matthews’ teacher, a Ms Meredith, gave him 21 out of 20 (more than the maximum) and, according to Matthews, christened the piece a short story and declared that Matthews was a writer.

Like many who wanted to be writers, Matthews was drawn towards journalism. Initially this was only towards low-level jobs close to the newsroom – after leaving school in standard eight he held jobs as messenger, clerk and switchboard operator. “James had begun as a messenger boy running errands, moving slowly up the ranks as the night telephonist and a clerk at The Cape Times,” according to the DSAC text titled James Matthews: A Dissident Poet. He did these jobs even while continuing with his creative writing. While a messenger at the Cape Times, one of the journalists assisted him with access to a library. This allowed him to take his reading beyond thrillers by writers such as James Hadley Chase.

By 17 years of age, he had his first story in print. In those days, newspapers or magazines were the medium for releasing single stories. After this first byline in The Sun newspaper, he went on to have short stories published in Golden City Post and Cape Times Magazine, Hi-Note and Drum.

For much of his life, the short story and journalism tracks ran together. He entered journalism by the freelance door, contributing articles to publications such as Golden City Post, Drum and The Cape Times. At some stage Drum employed him – and by 1955 he was its point person in the Cape. At that time, Can Themba was deputy editor, Es’kia Mphahlele the literary editor, and the magazine boasted a galaxy of dashing reporters with diverse writing styles. Matthews made his first short story submission to Drum magazine in 1954, a piece called The Champ, followed by more entries later that year. This was a boom period for short stories at Drum, a season that would end in about 1958 when Mphahlele resigned and was not replaced.

James made full use of this milieu, this space of mutual inspiration. His sense of calling as a writer deepened, and short stories – most with a biting view of the realities faced by the Cape oppressed communities – rolled off his pen. The link to the Drum writers complemented Matthews’ Cape-Town based writers group that Rob Gaylard termed District Six Writers and which Richard Rive calls the Quartet group: Alf Wannenburgh, Alex La Guma, Richard Rive and James Matthews.

Referring to the group, Gaylard says: “Unlike the Drum writers, they did not publish in the same magazine or share the same workspace. Their association arose from personal contact with each other.” Gaylard also observed that whereas “the Drum writers leaned towards a popular literature whose primary purpose was to entertain, and whose stock characters were the gangster or tsotsi, the detective, the good-time girl and the shebeen queen”, the District Six writers were probably more forthright and uncompromising. These debates are too detailed to go into here, save to note that Chapman took one view – that socio-political realities of black urban life carried over into Drum writers’ fiction and ensured a degree of social relevance – and writers like Lewis Nkosi and Njabulo Ndebele adopted another. Nevertheless, the Drum era constituted lively journalism, a go-getting vibe, imaginative writing and, as Es’kia Mphahlele would have it, a case of “the black man writing for the black man. Not addressing himself to the whites”. It was into this setting that James Matthews and his fellow Cape writers injected something particular – that more pronounced ‘dissident’ tone.

In a signal move that fell within this period, in 1956, Matthews, Clarke and Richard Rive experimented with the idea of jointly writing “a sketch of a young coloured delinquent, analyzing aspects of his mentality and history”, and persuaded a skeptical Drum editor to publish. The three pieces were laid out side by side under the heading Willie-boy. Matthews’ piece was called Downfall.

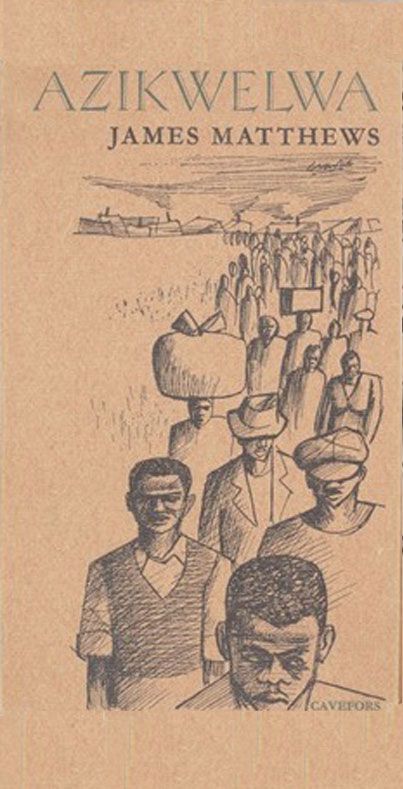

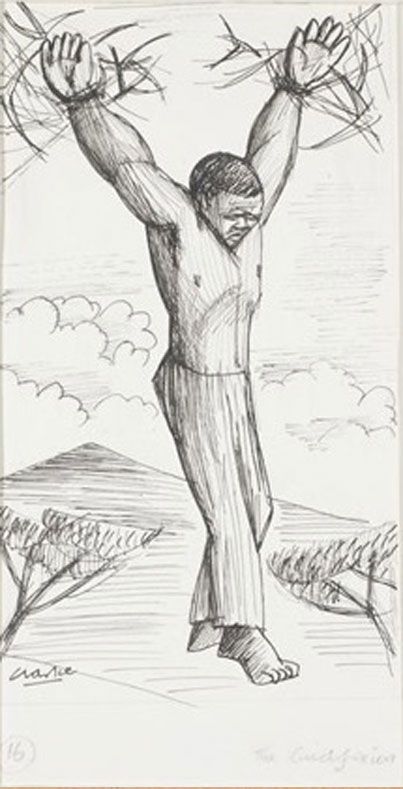

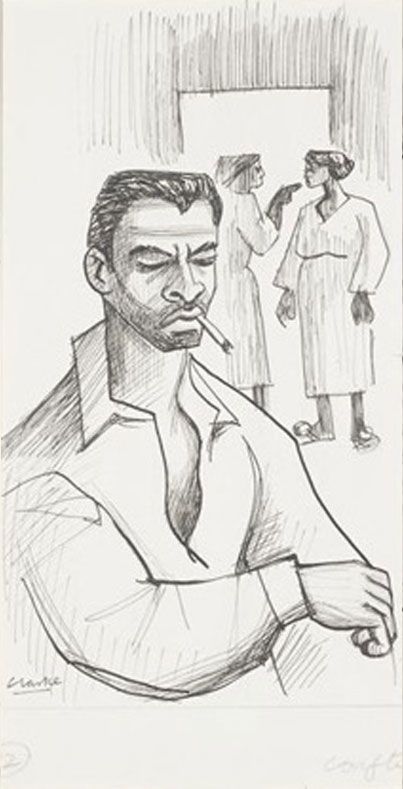

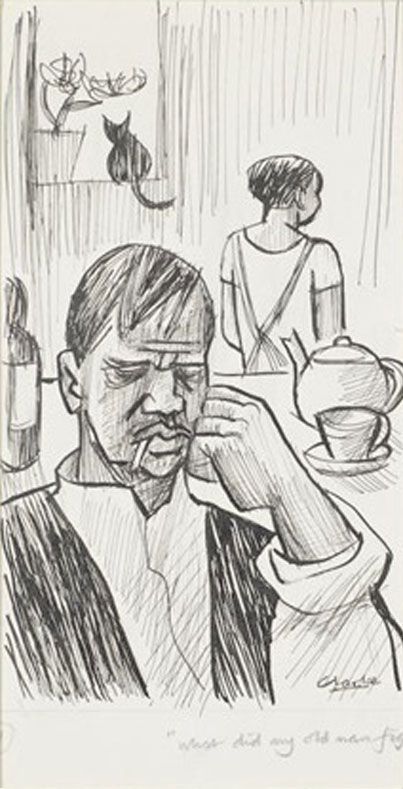

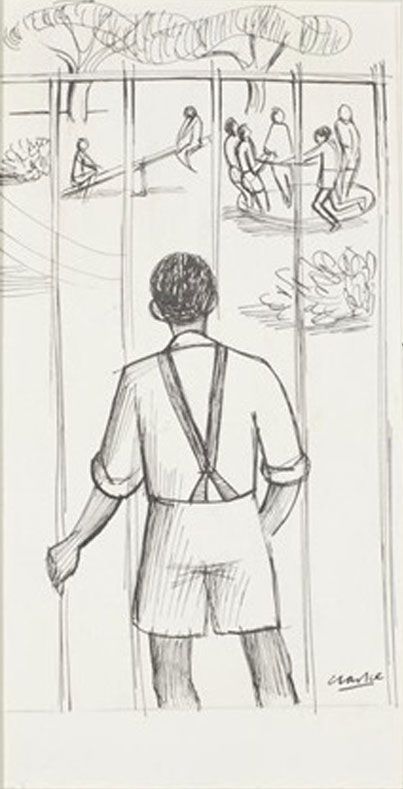

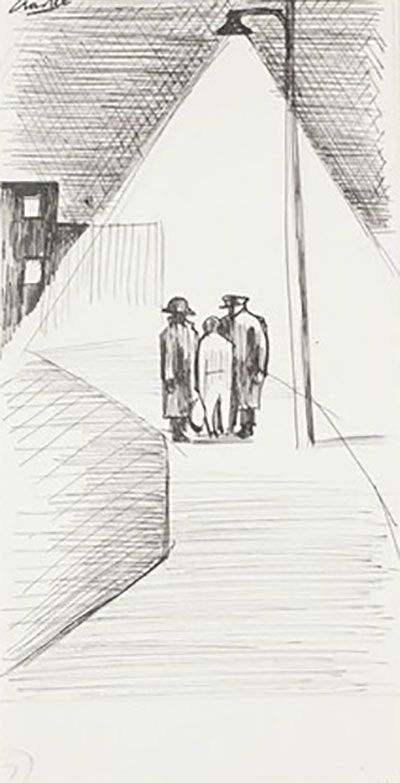

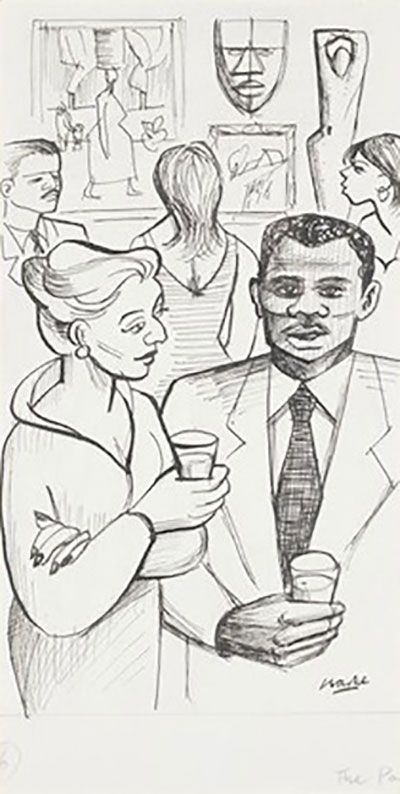

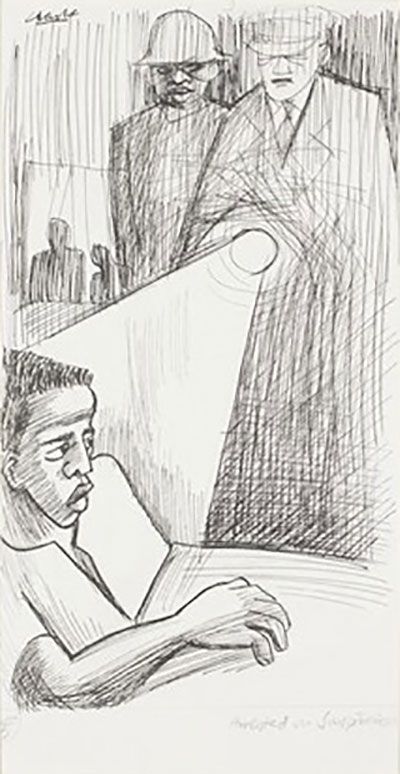

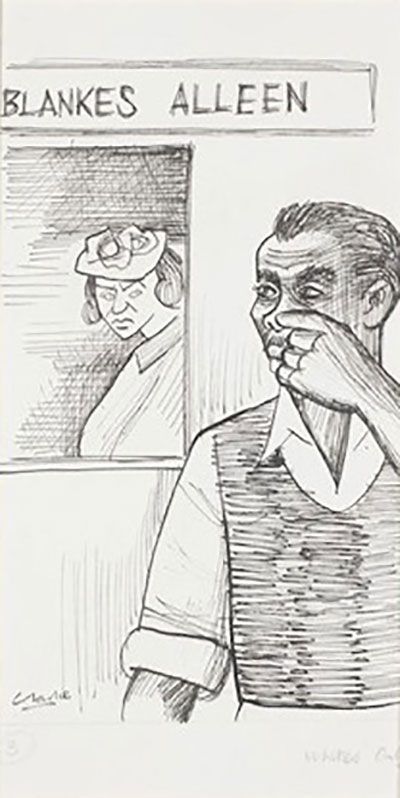

Based on his prolific output, Matthews produced a debut collection containing 16 stories – published in Sweden in 1962. It was titled Azikwelwa and illustrated by artist and close associate Peter Clarke. Four of these stories, The Park, Portable Radio, Azikwelwa and The Party went into Quartet, a joint endeavour with Richard Rive, Wannebergh and La Guma. Quartet was published in the US in 1963 and republished for SA consumption almost a decade layer. Both were banned in South Africa.

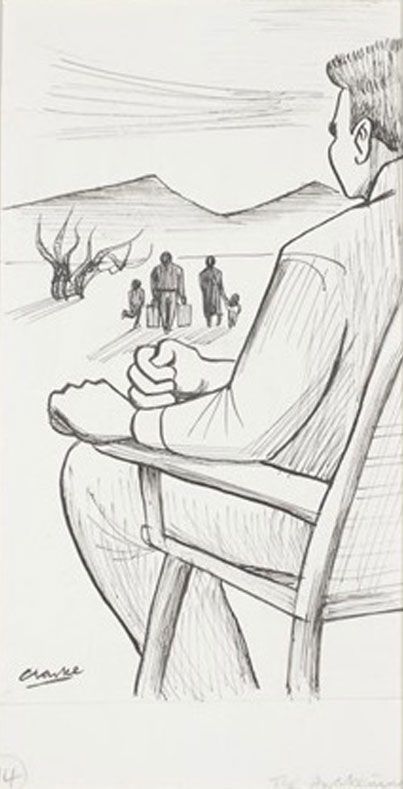

Azikwelwa takes place in the Alexandra bus boycott. It depicts the resilience of protestors and shows the transformation of a character who was initially opposed to the boycott. At the centre of the story is the issue of dignity; a collective display on dignity became a powerful magnetic force on the protagonist Jonathan. According to Nadine Gordimer, in this piece Matthew “shows not generalized heroic or saintly figures, but ordinary, frightened men, driven to find themselves through experiences they half-shrink from, tempted to prefer deprived life to the danger of risking what little they have in the hope of attaining something better”.[1]Michigan Quarterly Review (Vol. IX, No, 4. Fall, 1970 ), Nadine Gordimaer gave the Hopwood lecture. ‘Themes and attitudes in Modern African Writing’, p. 228. Like the writing of Harry Gwala in the 1940s, the work is set in an organisational and mobilisation context and, like Gwala’s prose, it holds up well as a work of art.

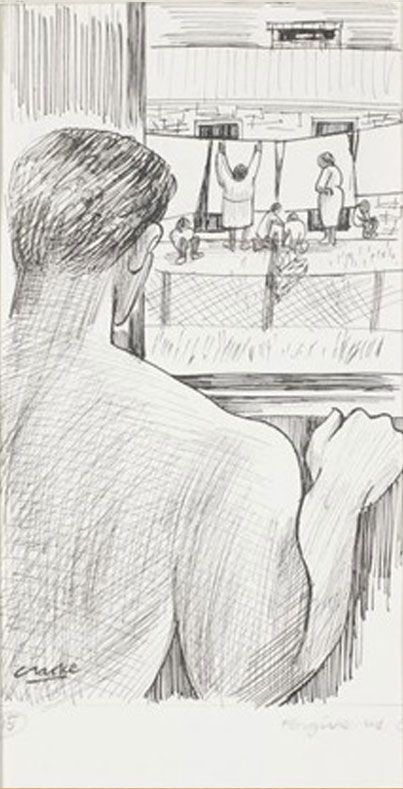

James Matthews’ story, The Park, is a jewel in Quartet. In this story, a boy who assists his mother with laundry delivery comes face-to-face with racial discrimination. The story starts and ends with the boy looking longingly at the swings and other play equipment in the park. The story has echoes with Oswald Mtshali’s poem, Boy on a Swing, where the boy’s pleasure at riding a swing is rudely interrupted by painful thoughts of apartheid reality. In Matthews’ story, the unnamed boy enters the Park and drinks deeply from the cup of life. He soars higher. At this point the swinging, the heights it can reach, becomes a symbol for being free – of gay abandon and the soul in its natural state. Thus Matthews writes: “He could touch the moon. . . . The earth was far below. No bird could fly as high as he. Upwards and onwards he went”. But then, the park attendant arrives with the Whites only message. Nothing is clichéd as Matthews brings home the experience of the child under apartheid – and we see the child’s basic yearnings, his closeness to his mother and her resilience just as we see the dilemma of the park attendant who must do his job but also has a deep empathy with the child’s desire to use the swings.

In Portable Radio, a character who comes in to some money buys a radio. Having found the money, the character makes a dash to obtain external trappings as a way to win back some sense of pride. This story shines a spotlight on how, among some of those who have had their dignity systematically stripped, those with money give in to shallow aspirations and superficial displays of wealth. As the story ends and the lead character’s money dries up, things sink back to the way it always had been. The story suggests that, absent of community members finding ways to restore what was broken and interrogating received values, the arrival of financial bonanzas serve only to expose the cracks and hollowness of the system.

Mathews examines closely the human condition under the oppressive conditions that prevailed. And here, he looks deeper than the race issue. “(I)t’s not only a racial thing, it’s also a class thing,” he told an interviewer.[2]Interview with James Matthews At the same time, he is searching for values that matter. Although he was extremely publically motivated, his stories were so much more. Matthews’ stories showed a deep concern with the journeys of characters. His skillfully-crafted descriptions and faithfulness to the narrative thread showed his commitment to good writing.

Academic Hein Willemse notes that Matthews took a conscious decision to abandon short story writing. This occurred as the apartheid system tightened its grip and – as a counter to it – a renewed political mobilisation in the form of the Black Consciousness Movement was taking off.

“James turned to poetry when writing political short stories became, in his words, ‘a daunting challenge’”, Willemse wrote. “This turn in his creative output coincided with a shift in our social and political environment. It became harsher than ever before,” he added.[3]James Matthews a revolutionary poet Thomas Penfold, referring to this switch in the early 70s, states: “Poetry, he felt, was a form more suitable for rapid and accessible declarations”.[4]Penfold, ‘Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation’ in South Africa, University of Birmingham theses, p. 150.

Matthews’ own view of his work and where it fitted in can be complicated. At times, James identified with his calling as a writer, moving in writerly circles. At other times, it feels as if Matthews wanted more of the very things academics would lambast him for – directness, more message-driven work, and a strong focus on changing the system, factors that can undermine the aesthetic element of a work.

Matthews was never a political party person, at least not in the same way that, for example, Wally Serote was. He was never a card-carrying member of a political organisation. His earliest stories were apolitical. According to Gaylard, it was after engagement with La Guma and, as a mentor of sorts to him, the Communist Party’s Wolfie Kodesh, that his political sensibility increased. At the same time, he worked on developing his writing skills. He fine-tuned his craft in an informal writing group he shared with Wannenbergh and La Guma, a process which – together with exchanges he had with Richard Rive and Peter Clarke – would have underlined elements such as subtlety, a deeper understanding of human motivation, more open-endedness to stories and authentic characters with flaws and frailties. Both of these factors – “an interest in the political side of what stories could mean” (as Matthews put it) and his growing literary awareness – created the depth in his stories.

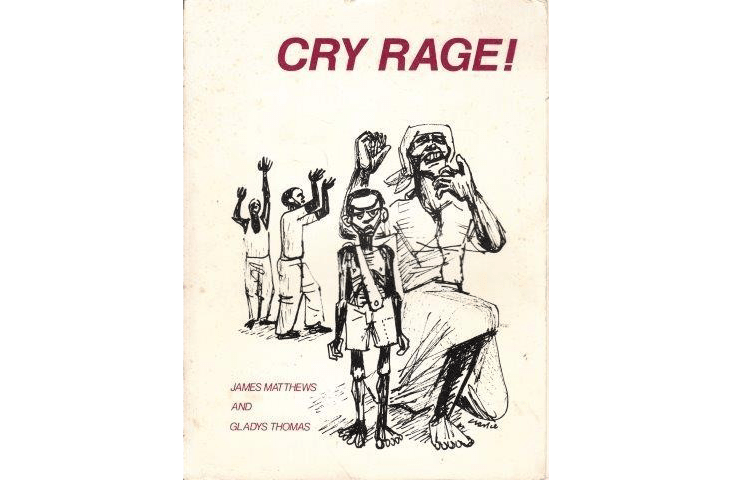

“I first wrote because of my background; my short stories dealt mainly with poverty,” Matthews said in an interview with Daniel Magaziner.[5]Interview with James Matthews “I then became more interested in trying to write about the political situation, how it effects and not too much the political situation with slogans – the people’s sayings, the people’s suffering and not an ideological party.” But by the late 60s, Matthews’ trajectory was taking him towards greater stridency. His prose was not militant enough, he said. He felt shackled by the requirements and conventions of the short story, he told Magaziner. “With the poem, I form my own structure,” he said. He further noted that his stories lacked the militancy of Cry Rage.

Not only did he want the directness of poetry, he also wanted to be on the outer edges of the poetry frame – to explore anti-poetry. “(S)ome of us weren’t interested in the whole poetry bag – we were just writing things; others labeled it poetry (and) stupid observers said ‘protest poetry’, which is such a bullshit term”. He once called his poems ‘utterings’ and on the title page of Pass Me A Meatball, Jones as “a gathering of feelings.” In some ways, he succeeded at being the master of un-poetry – Gordimer said in 1973 that Matthews’ poetry was “a public address system for the declarations of a muzzled prose writer”[6] Gordimer, Nadine. 1973. ‘Writers in South Africa: The New Black Poets’. Dalhouse Review. 53.4: 645- 64 (this specific quote is on p.663). and Penfold slammed his work as “leaning towards a linear poetry of facts, slogans, simple similes and metaphor.”[7] Penfold, ‘Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation’ in South Africa, University of Birmingham theses, p. 150. At the same time, this aspiration of remaining a stepchild in the poetry world was dashed; in an article published in 2019, Willemse declared that “it is hard to think of South African political poetry without the name of James Matthews”.[8]James Matthews

Regardless of how he views them, Matthews has left an important legacy in his short stories. Matthews may have turned away from story writing and many profiles speak only of the dissident poet, but his short stories stand as a beacon on the South African literary landscape, have enriched the South African short story tradition and, taken together, powerfully demonstrate the role of the arts in social transformation.

James Matthews – Taxi To Town (1992)

| 1. | ↑ | Michigan Quarterly Review (Vol. IX, No, 4. Fall, 1970 ), Nadine Gordimaer gave the Hopwood lecture. ‘Themes and attitudes in Modern African Writing’, p. 228. |

| 2. | ↑ | Interview with James Matthews |

| 3. | ↑ | James Matthews a revolutionary poet |

| 4. | ↑ | Penfold, ‘Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation’ in South Africa, University of Birmingham theses, p. 150. |

| 5. | ↑ | Interview with James Matthews |

| 6. | ↑ | Gordimer, Nadine. 1973. ‘Writers in South Africa: The New Black Poets’. Dalhouse Review. 53.4: 645- 64 (this specific quote is on p.663). |

| 7. | ↑ | Penfold, ‘Black Consciousness and the Politics of Writing the Nation’ in South Africa, University of Birmingham theses, p. 150. |

| 8. | ↑ | James Matthews |