CHRIS ALBERTYN

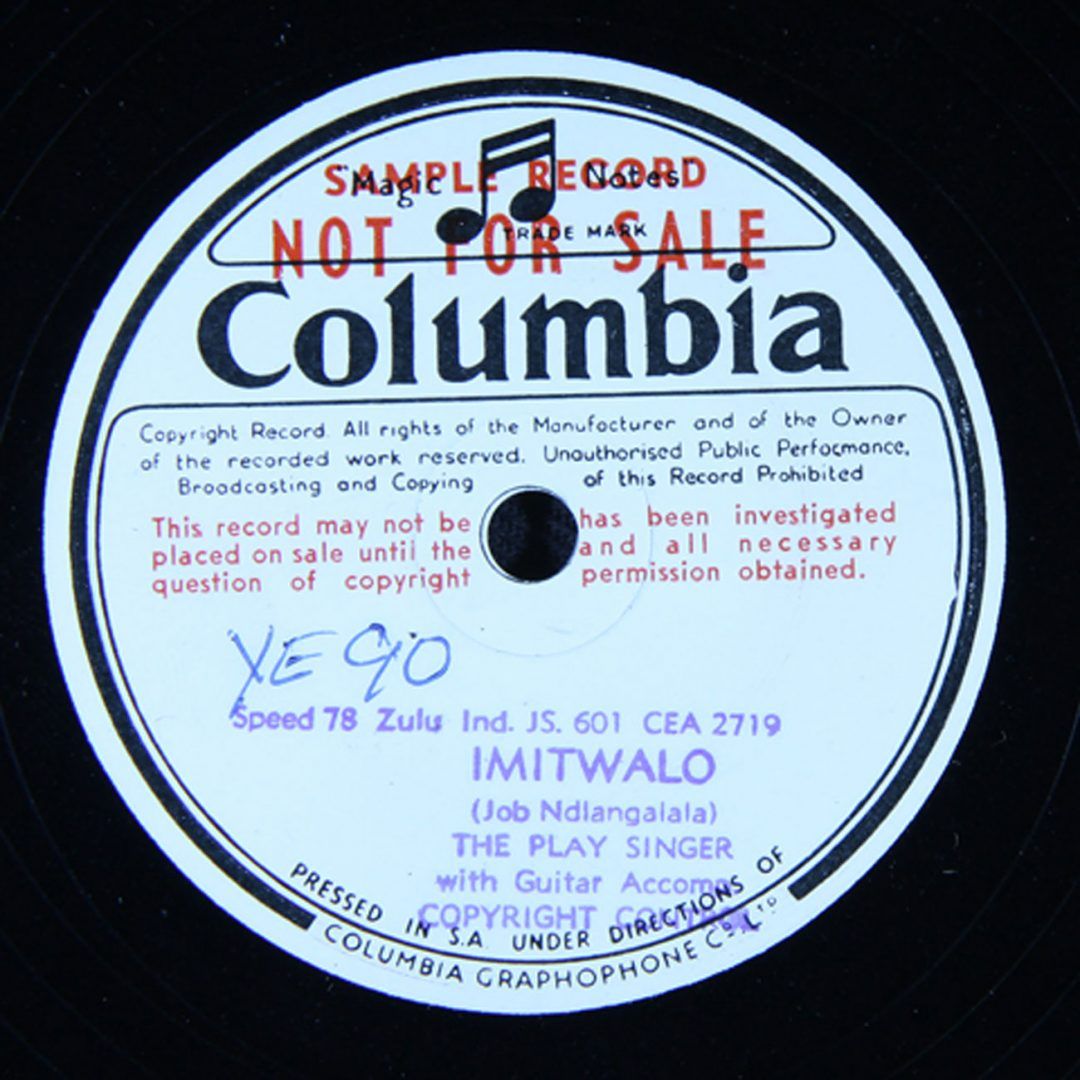

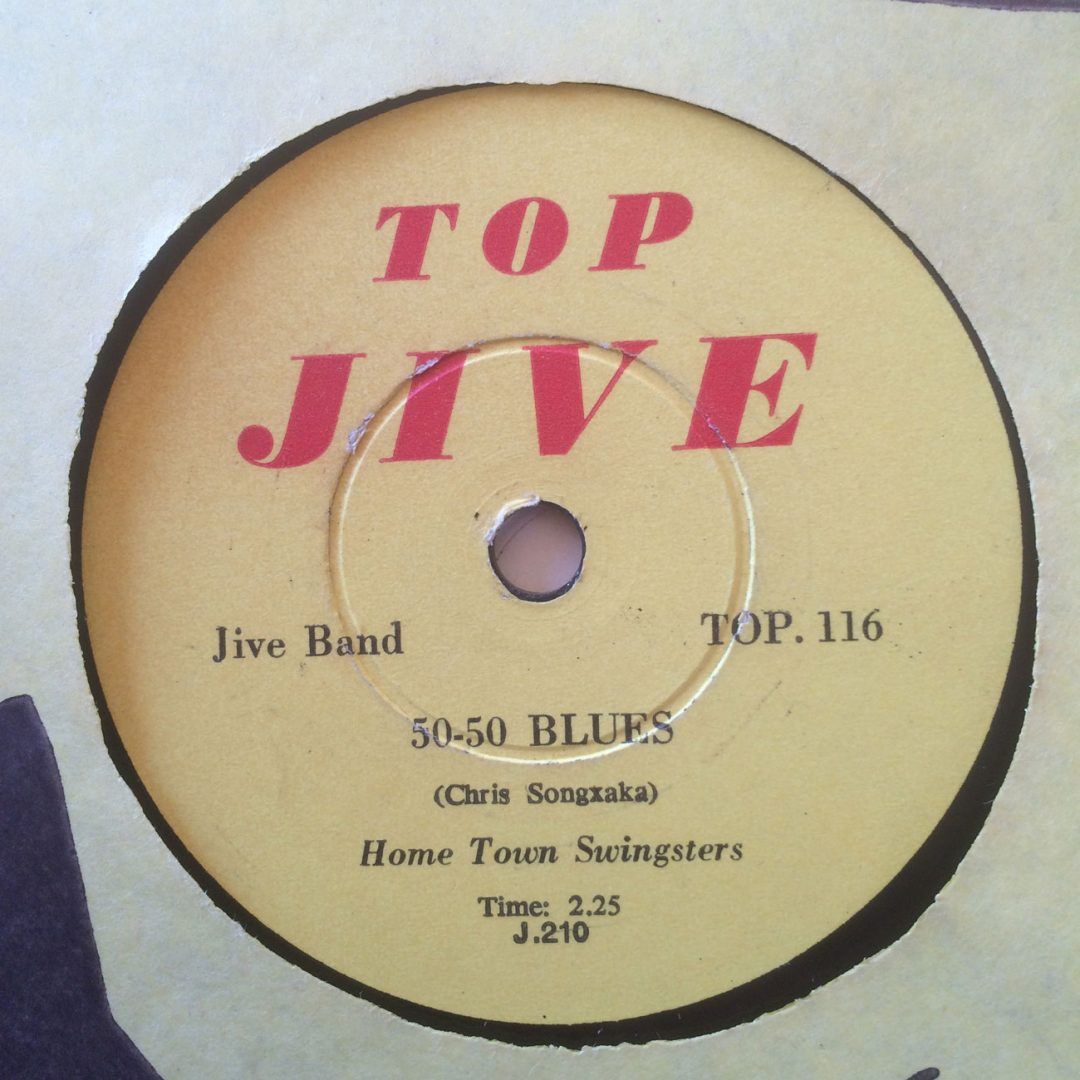

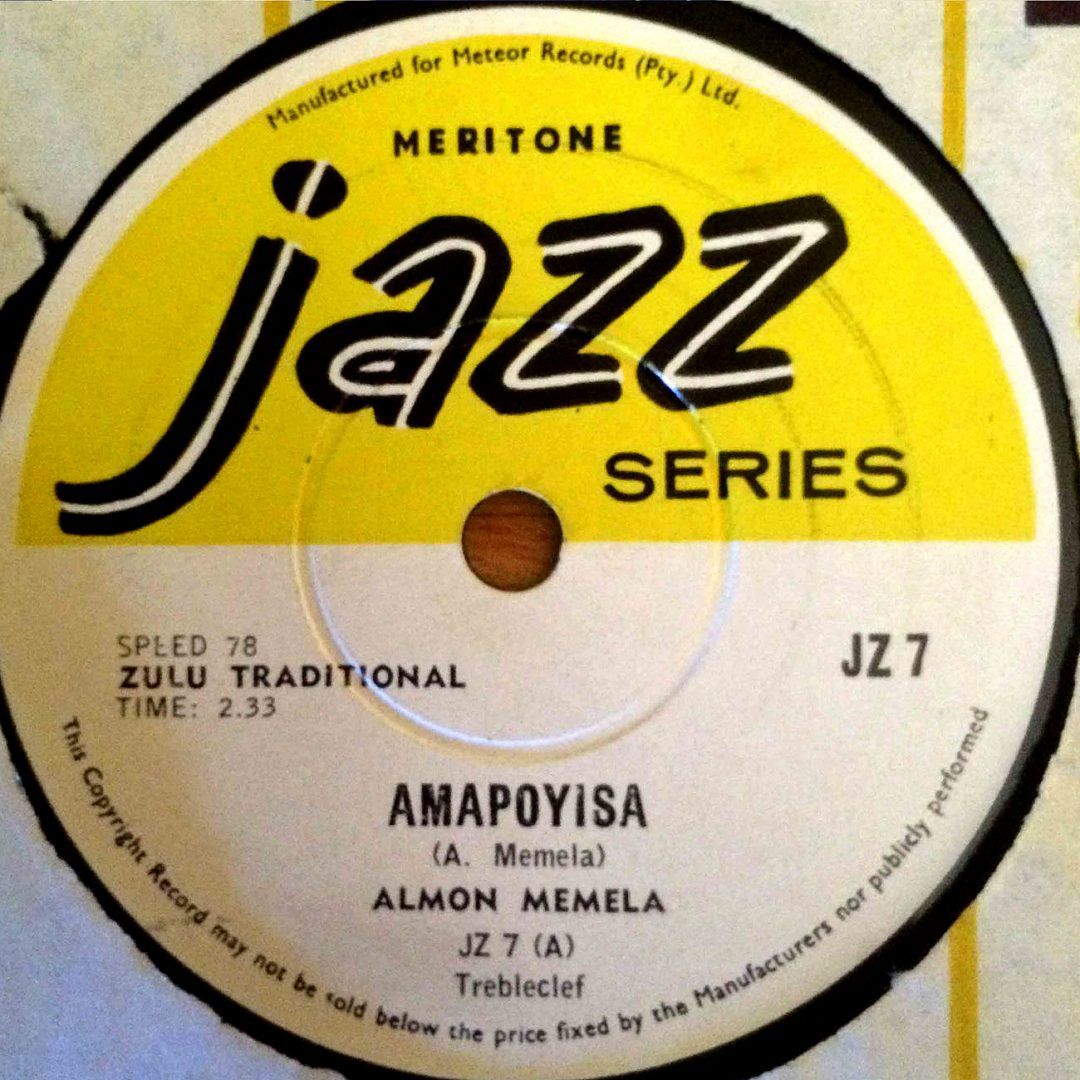

Lost, unknown and forgotten: 24 classic South African 78rpm discs from 1951-1965.

It’s a cruel warp of history that a musical flowering, an explosion of diverse South African cultural expressions during the 1950s and 1960s, is mostly unknown, lost, and forgotten. Originally pressed on ten-inch shellac records, very few of these discs have survived. Furthermore, thousands of the original master tapes no longer exist. In a relentlessly evolving, profit-driven music industry, these recordings effectively became disposable music. But, much of that might all be about to change.

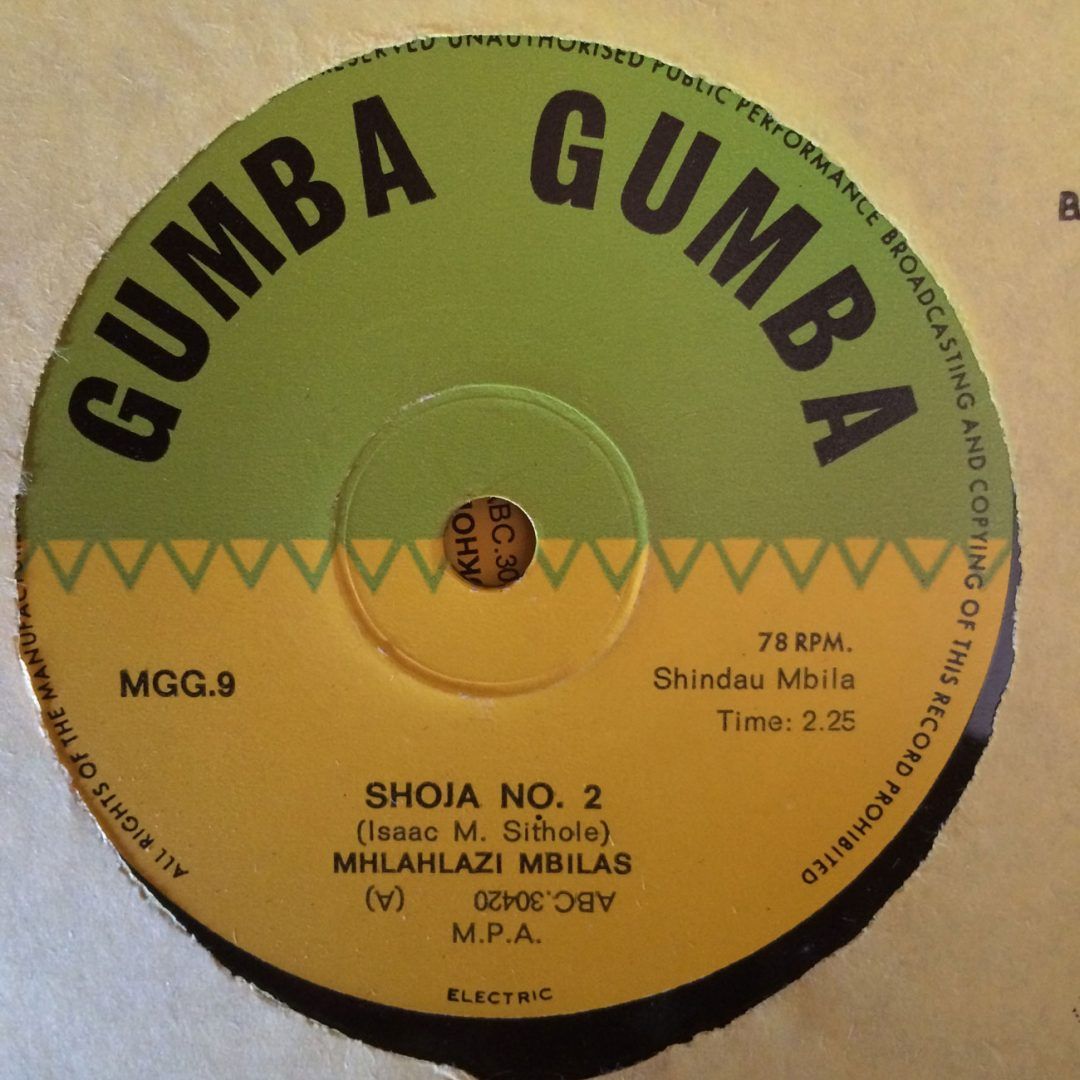

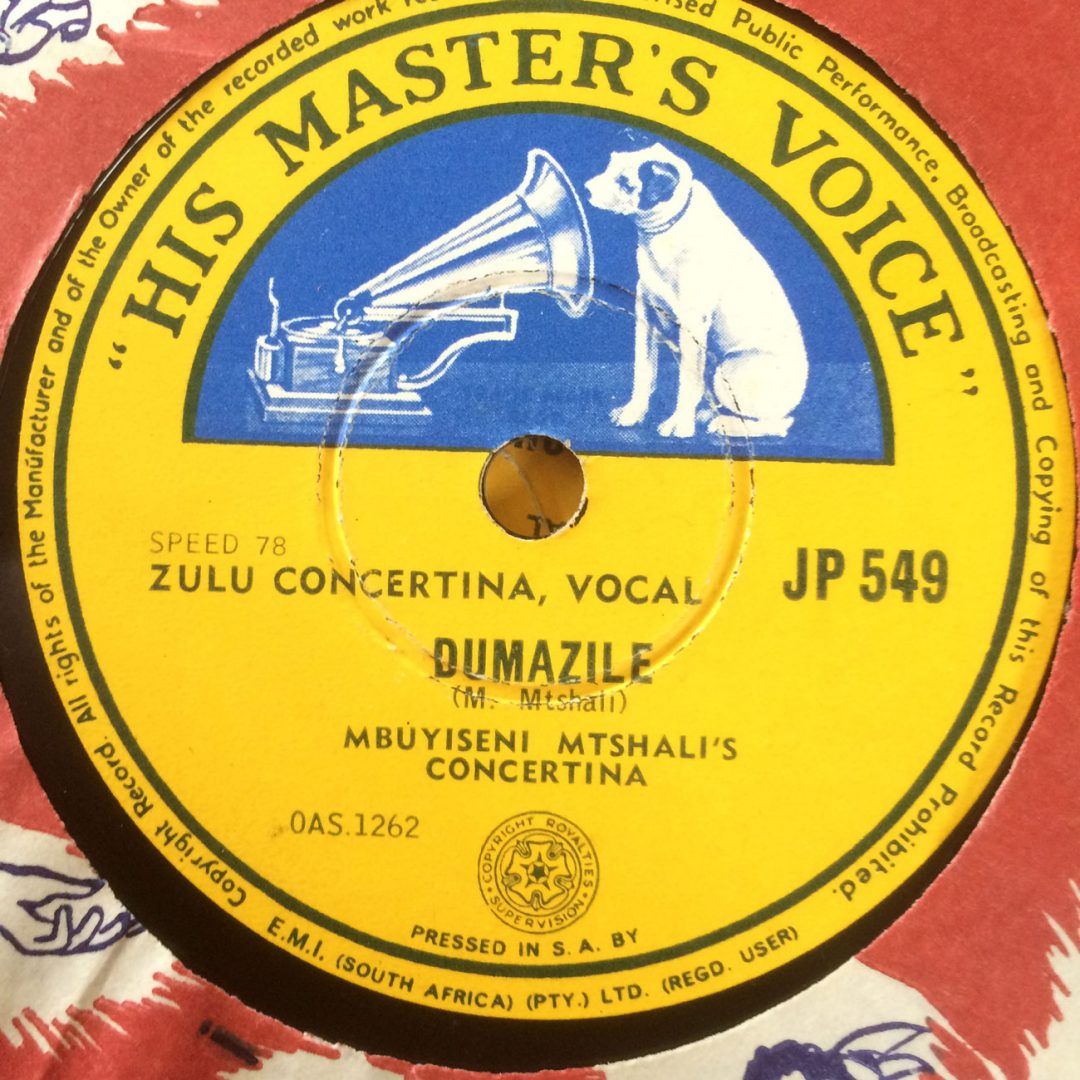

The 1950s saw technological advances which meant that records and players became affordable to a much wider audience. Multiple record pressing plants sprang up around Johannesburg between 1949 and 1952, from companies such as Trutone, Gallo, EMI and others.

An explosion in private ownership of 78rpm records among an African target market was further reinforced by developments in radio broadcasting. A new, hitherto unheralded, era of diverse popular African musics “went viral”. They became available to anyone with access to a record player or radio. It became easier to hear contemporary music without actually having to be in the moment and at the place it was played.

For example, from 1954 through to 1964, the genius that was Gideon Nxumalo hosted a highly popular weekly “This is Bantu Jazz” show on the rediffusion radio services of the South African Broadcasting Corporation. Nxumalo earned his nickname “Mgibe” (The Trap), precisely because his show shaped tastes, and motivated his large audience into buying hundreds of thousands of 78rpm records.

Of course, the portability of radio and records also meant a much greater accessibility to, and influence of, incoming popular international music. More than ever, there was a staggering choice and diversity of musical genres, fashions and fusions being composed, played and recorded.

Sales of 78rpm record players and shellac discs in South Africa rocketed. The burgeoning music industry diversified and took chances, recording and pressing examples showcasing an amazingly broad range of genres – from traditional, through religious, choral, maskandi, swing, jazz, marabi, blues, jive, doo-wop, rock ’n roll, twist, and quite a few trends and gimmicks in-between.

While no one really knows, informed guesstimates are that as many as sixteen thousand recordings (more than 8000 different shellac discs) targeted at an African audience were pressed in Johannesburg. Each record was usually pressed in runs of between 300 and 350, with the popular issues being re-pressed multiple times. Doing the sums, that means at least three million 78rpm records of African music were sold over this time. In the 1950s, each record changed hands for between three shillings and ‘three and six’. In today’s inflation-adjusted terms, that would be about R35.00 per disc containing two songs.

Shellac 78rpm records were selling so well to the African market that South Africa was among the last countries in the world – in 1968 – to stop pressing in this format. English and Afrikaans recordings were transitioned from shellac to vinyl pressings at slower speeds in the early 1960s.

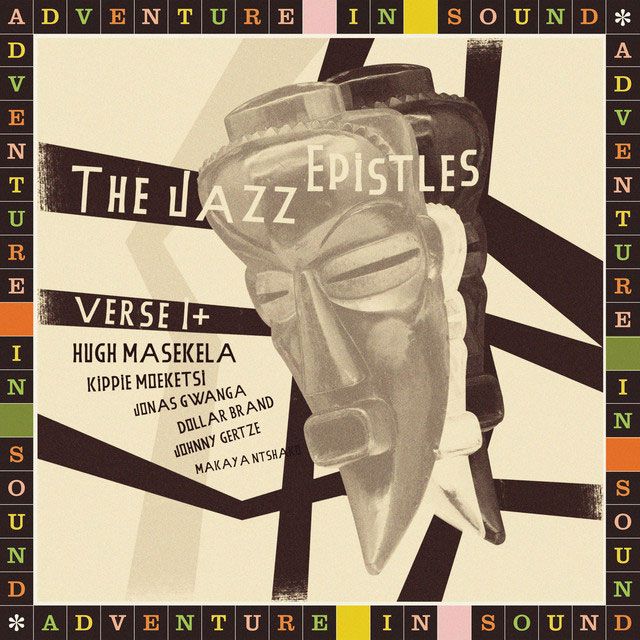

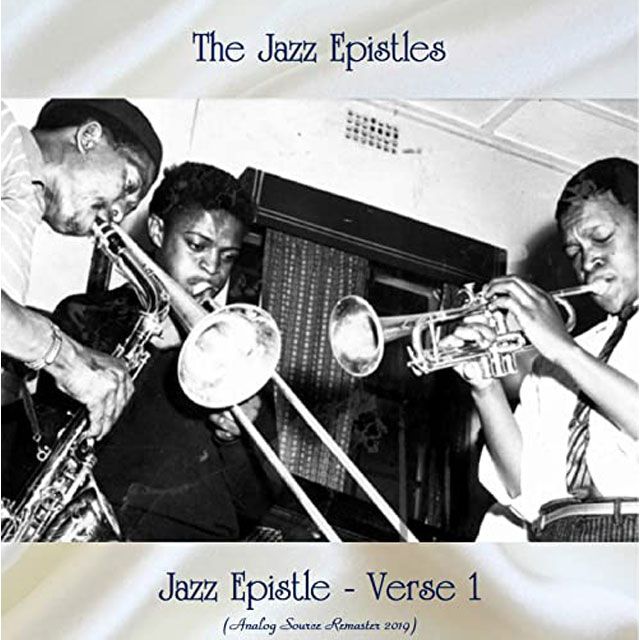

The first African jazz record, by the Jazz Epistles, (Verse 1) was recorded in 1959 and was pressed on vinyl long-player at 33rpm speed. In the same year the King Kong musical was also pressed to vinyl at 33rpm and it sold in excess of 25,000 copies.

But, nonetheless, there were so many African households that owned 78rpm players, it apparently made commercial sense to the music moguls to keep pressing music for the “African market” in the shellac ten-inch 78rpm format.

These fragile discs, collected in households in Sophiatown, Alexandra, Orlando and multiple other mostly urban locations right across the country, did not last long. If wear and tear did not destroy them, then apartheid’s forced migrations and relocations denied the possibility of permanent family storerooms where collections could be kept and handed down across generations.

There was, and still is, no official public archive of this music.

The Troubadour label alone issued an estimated 3000 African records (6000 songs) on 78rpm, counting their sub-labels like “HIT”, “Goli” and others. Sadly, their entire archive of master tapes was thrown away in the early 1970s when Gallo took over the Troubadour studios to use as rehearsal rooms. All of the Teal Company’s 1,600 master recordings were also thrown away, while a 1972 fire at the EMI warehouse destroyed around 8,400 recordings, plus a whole lot more English and Afrikaans recordings.

Legendary Gallo archivist Rob Allingham estimates that the master tapes of perhaps fifty percent of all the recordings made in the 1950s and 1960s have been destroyed. Fragments of this destroyed archive of recordings remain on those 78rpm discs that have somehow survived. As for the other 50%, these master recording tapes still exist.

Nowadays, original copies of these 78rpm records are challenging to find. A handful of collectors around the world do have some important collections, with pieces going way back in time to the first recordings made in 1912. The International Library of African Music in Makhanda has an extensive African (South Africa and beyond) archive as a result of Hugh Tracey’s exceptional work. The National Archive of Zimbabwe has around 900 discs of South African 78rpms (no such archive in South Africa), while it is suspected (hoped) that the South African Broadcasting Corporation has preserved what should also be an extensive archive. Mostly, these collections and archives are not accessible to a broader public – meaning that this music remains unheard and unknown, until … enter Black Coffee.

In 2020 South African DJ Black Coffee paid Lebashe Investment Group an undisclosed sum for a significant stake in Gallo Music Investments – the holders of South Africa’s most extensive musical archives. The press release at the time reads:

“… it is our intention to explore and reintroduce these amazing classical archives to our mainstream market, locally and globally. The collaboration with internationally renowned DJ Black Coffee will usher in a new era for the South African music business on a global scale”.

Black Coffee is quoted as saying:

“This is the first of many moves we are working on to change the landscape of both the South African and African music industry. The music in the Gallo catalogue is some of the most culturally rich that has ever been created in this country. The partnership with Lebashe to invest in the catalogue and masters, is more than just a business transaction – it’s about creating an environment in which artists and creatives have a truly equitable stake.”

If you head over to Bandcamp and search Gallo, you will find they are building a commercially available digital archive of “African Classics” – 69 albums and artist compilations so far, and counting. Word is that by 2025 we can expect to see all of Gallo’s master tapes from the 1950s and 1960s, and beyond, digitised and available for sale. A whole new world!I am interested to know how the complex and complicated business of identifying beneficiary relatives for royalty payments might pan out.

Most of the artists in the 1950s and 1960s (and beyond) were paid a once-off studio fee. While composers are documented, this too is a fraught and complex minefield of appropriation and contest.

It is a curious quirk, and synchrony, that if you do decide to purchase two digital tracks from that era from the Gallo Bandcamp site, you will pay $1 U.S, for each track … which amounts to around ZAR35.00 … which matches the inflation-adjusted three shillings and sixpence a 78rpm disc cost in the late 1950s. While I celebrate and look forward to the opportunity of hearing this previously hidden and lost music; for me personally a digital file does not satisfy in the way that a re-issued vinyl compilation might.

The following selection is a personal one-hour compilation of 24 songs digitised from original 78rpm shellac records, chosen to represent a cross-section of some of the genres popular at the time.

Thanks to Siemon Allen at Flatinternational for confirming the dates of these recordings, and, along with Rob Allingham, for your generosity with various details and helping with estimates of numbers.

As for the fidelity of the sound, if one has the correct equipment, the mono sound quality of these 78rpms can potentially be excellent – some effort is needed in matching the right analogue equipment, especially stylus size and shape, according to the label and year. And then there is some digital re-mastering after that. Each record label sold their own record player, and pressed their own records at a groove-width to match their players … if you play a 78rpm with the wrong size or shape stylus you will then get lots of surface noice. I have styluses/stylii of different widths (50 to 70 microns) and shapes (spherical for the more worn records, and eliptical for those in better condition).