CHARL-PIERRE NAUDÉ

Dekonstruksie as gebundelde terrorisme

Deconstruction as curated terrorism

Charl-Pierre Naudé se resensie van Aryan Kaganof se eksperimentele teks Die wrede relaas van Vuilgat en Stilte staan van meet af uit omdat dit begin met ’n onomwonde verklaring – iets wat party resensente vir die einde hou, en waarby ander nooit uitkom nie. Tussen dié sterk begin en die oop vraag aan die einde, is ’n resensie wat konteks bied en vars inligting opdis wat as noodsaaklike sleutel dien om ’n dikwels verbluffende boek vir die leser te ontsluit. Waar Naudé ander boeke en skrywers by die resensie betrek, is die relevansie duidelik en die vergelykings verhelderend. Die literêre teorie rondom cento word soomloos in die resensie verpak en daar word voorbeelde en konteks verskaf om uit te wys hoe dit in die boek funksioneer, asook verduidelik wat die funksie van dié tegniek is. Naudé kry dit reg om die inhoud van die boek duidelik oor te dra en gee die leser ’n goeie gevoel vir wat hulle op stylgebied te wagte kan wees. Die aanhalings uit die boek is slim gekies om die voorsmaak te versterk terwyl dit Naudé se punte staaf en sy argumente ondersteun. Die resensie is vol humor en geweldig leesbaar. Naudé is ’n skerp leser wat verbande trek, interessanthede, speletjies en simboliek opmerk en uitwys, en vars insigte en interpretasies na sy resensie bring. Sy vermoë om sinne te skryf wat die essensie van ’n boek in ’n paar woorde vasvang, is ongeëwenaar.

KykNet Rapport Commendatio 27 September 2021

Charl-Pierre Naudé’s review of Aryan Kaganof’s experimental text The Cruel Tale of Dirty Arse and Silence stands out from the start because it begins with an unequivocal statement – something that some reviewers keep for the end, and which others never get to. Between this strong start and the open question at the end, is a review that provides context and dishes out fresh information that serves as an essential key to unlocking an often astonishing book for the reader. Where Naudé involves other books and authors in the review, the relevance is clear and the comparisons illuminating. The literary theory surrounding the cento form that Kaganof uses in the novel is seamlessly packaged in the review and examples and context are provided to show how it functions in the book, as well as explaining what the function of this technique is. Naudé manages to convey the content of the book clearly and gives the reader a good feel for what they can expect in terms of style. The quotes from the book are cleverly chosen to enhance the foretaste while corroborating Naudé’s points and supporting his arguments. The review is full of humor and extremely readable. Naudé is a sharp reader who draws connections, notices and points out interesting things, games and symbolism, and brings fresh insights and interpretations to his review. His ability to write sentences that capture the essence of a book in a few words is unparalleled.”

KykNet Rapport Commendatio 27 September 2021

Dit is een van die oneerbiedigste en ontsporendste tekste (albei in die beste sin van die woord) wat tot nog toe in Afrikaans verskyn het. Dis ’n hoogtepunt vir die uitgewer Naledi.

This is one of the most irreverent and derailing books (both in the best sense of the word) that has yet appeared in the Afrikaans language. It’s a highlight for publisher Naledi.

Kaganof het as eksperimentele fliekmaker onder die naam Ian Kerkhof bekendheid verwerf en is as Engelstalige skrywer ook bekend. Hy was lank in Nederland as politieke uitgewekene voordat hy na Suid-Afrika teruggekeer het, wat saamgeval het met die verandering van die naam. Dit is sy eerste gepubliseerde teks in Afrikaans en as radikale eksperiment verveel dit beslis nie. Dis by tye poëties, skreeusnaaks,platter as platvoers. En dis ’n opsetlike en wydlopige (ook loopse) verleentheid vir enige selfbewuste, literére fynproewer.

Kaganof gained notoriety as an experimental filmmaker under the name Ian Kerkhof and is also known as an English-language writer. He spent a long time in the Netherlands as a political expatriate before returning to South Africa, which coincided with the name change. This is his first published text in Afrikaans and as a radical experiment it certainly isn’t boring. It’s poetic at times, screamingly funny, more vulgar than vulgar. And it’s a deliberate and sprawling (and on heat) conundrum for any self respecting literary connoisseur.

Die ontsporende struktuur en wispelturigheid herinner aan Naked Lunch van William Burroughs, maar as aanstoker tot diepsinnige nadenke herinner dit weer aan tekste soos Waiting for Godot deur Samuel Beckett. Albei hierdie tekste word in Kaganof se teks opgeroep deur middel van cento, ’n interresante “genre” waarin die skrywer ’n teks saamstel uit passassies of idees wat kom uit bestaande tekste.

The derailing structure and mercurial register changes are reminiscent of William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, but as an instigation to profound reflection it is reminiscent of a text like Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett. Both of these texts are evoked in Kaganof’s book by means of the cento form, an interesting “genre” in which the author composes a text from passages or ideas that emerge out of pre-existing texts.

So het die Belgiese skrywer Paul Bogaers ’n hele roman, Onderlangs (2007), geskryf wat uit sulke “gesteelde” passessies saamgestel is. Dis ’n tegniek wat soos die res van Vuilgat interessante postmodernistiese vrae vra oor die oorspronkelikheid en kreatiwiteit.

In this cento form the Belgian author Paul Bogaers wrote an entire novel, Onderlangs (2007), which was compiled exclusively from these “stolen” passages. Cento is just one of the many techniques used in The Cruel Tale of Dirty Arse and Silence that pose interesting post-modernist questions about originality and creativity.

Deur die naasmekaarstelling van frases uit disparate werke aktiveer cento gapings van betekenis tussen sulke passesies wat sluimerende was.

By juxtaposing phrases from disparate works, cento activates significant fields of meaning that were latent but dormant until the juxtapositions were made.

Ek kon ’n handvol sulke “diefstalle” plaas, ’n interessante passassie gelig uit Dashiel Hammett en ’n idee gelig uit Naked Lunch, die pratende poepgat, waarin ‘’n man se khaktonnel (só geskryf) alles leer wat die kop kan doen en die geplagieerde kop dan bedroë laat. Maar Kaganof skryf dit in sy eie woorde oor. Dit kan as metafoor vir cento gelees word. Die karakter Vuilgat ondergaan ’n enema waarin hy al sy kak aan die niet afstaan, maar twee dermdiere bly in sy gange agter, ene Frensch Johannes en Hendrik Balthazar.

I could recognize a handful of these “thefts”, an interesting passage lifted from Dashiel Hammett and an idea drafted in from Naked Lunch; the talking poephol, in which a man’s khaktonnel (so written) learns to do everything that the head can do (eat, talk, kiss) and then leaves the head behind, deceived. But Kaganof rewrites this episode in his own words. This could be interpreted as a metaphor for the cento itself. The character Dirty Arse undergoes an enema in which he surrenders up all his shit to the Nothing, but two intestinal dwellers remain in his bowels, a “Frensch Johannes” and a “Hendrik Balthazar”.

Die leser kry die prentjie. “Innie khakstorie is niks verbied nie” (bl.150).

The reader gets the picture. “In the khak story nothing is forbidden” (p.150).

“This is a delightful attack on the usefulness and self-perception of literature per se. It is deconstruction as curated terrorism.”

As ’n onkategoriseerbare, genrelose boeket van ontploffende kleur herinner Vuilgat aan die surrealiste en ’n skrywer soos Antonin Artaud. Die teks verskyn soos deels drama- of fliekteks en deels soos digkuns. Vuilgat is ’n manskarakter van onvaste en veranderende karaktertrekke en Stilte is sy meisie, ’n bruin wilgerlat-dingetjie wat soms na Kaaps oorslaan en daardie mooi Bolandse, benadrukkende intonasie besig, soos in: “Hoekom hou jy aan om my aannnssstoot te gee” Vuilgat wetie. Maar die woorde praat onderlangs, een stryk deur.

As an uncategorizable, genre-less bouquet of exploding colors, The Cruel Tale of Dirty Arse and Silence is reminiscent of the surrealists and a writer like Antonin Artaud. The book is written in parts as a theatre play, in parts as a movie script or movie text and occasionally as poetry. Dirty Arse is a male protagonist with fluid, constantly changing character traits and Stilte is his girlfriend, a brown willowy beauty that sometimes slips into Afrikaaps and then that beautiful Boland accent, emphasizing intonation, as in: “Why do you keep offffending meee?” Dirty Ass doesn’t know. But the words speak subterraneanly, until one strikes through the (un)consciousness.

Vuilgat se meisie vul die stilte met liefdeswoorde soos “fistfucking” en teen die einde van die relaas is sy ook Vuilgat, die khakskrywer, se ma (Vuilgat is ’n bekende skrywer van ongepubliseerde kakwerke.) Ek wil nie te veel weggee nie. Net sê: Dit sal roekeloos wees om hierdie teks se gekonstrueerde interteks met gelade kwessies, soos die rol van geweld in identiteitsvorming, te onderskat. Dis ’n heerlike aan val op die nut en selfopvatting van letterkunde per se. Dis dekonstruksie as gebundelde terrorisme.

Dirty Arse’s girlfriend fills the silence with the vocabulary of love; words like “fistfucking” and towards the end of the story she turns out all along to have been the khak story writer’s mother. (Dirty Arse is a famous khak story writer of an entirely unpublished khak oeuvre). I do not want to give away too much. Suffice to say: It would be reckless to underestimate the manner in which highly charged issues, such as the role of violence in identity formation, are woven into the text’s elaborate construction. This is a delightful attack on the usefulness and self-perception of literature per se. It is deconstruction as curated terrorism.

Die doek van swymelende betekenisse spring van die Middeleeue na ’n Kaapse plakkerskamp, dan na Parys en ook na die Bybel. Om die digter Adam Small by te haal, die Here het geskommel en wat Kaganof doen, is om dit te wys. Die sosiaal bewuste laag van die teks is navrant.

The canvas of intoxicating meanings jump cut from the Middle Ages to a Cape squatter camp, then to Paris and also to the Bible. To quote the poet Adam Small, the Lord shook things into being and what Kaganof is doing is to give literary form to this shaking. The socially conscious layer of the text is heartbreaking.

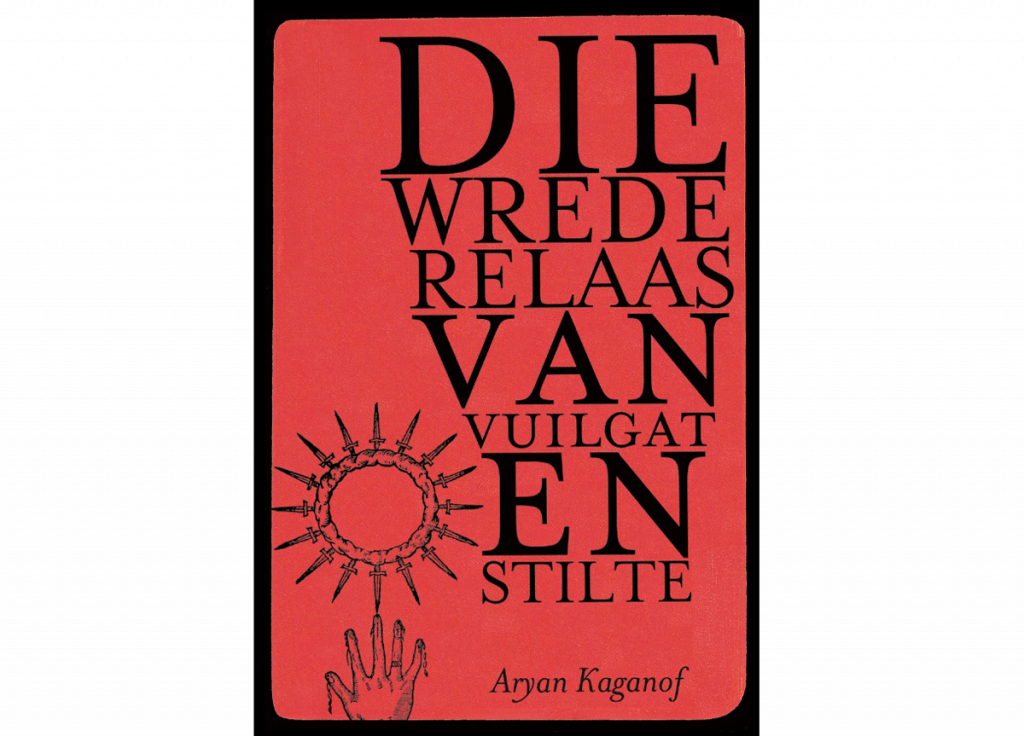

Die leser tref ’n mooi uitgawe aan waarin die titel in geëm boseerde letters verskyn, soos op ’n Statebybel. Daar is ’n afbeelding van wat lyk na ’n Middeleeuse tekening van ’n sekte in ’n hoek van die voorblad. Blaai dan na die teks se slotwoorde: “Toe hulle eindelik die grot oopmaak,/ oppie derde dag ná die steniging,/ was haar lyf weg.” Tussen hierdie twee meesterteks-verwysings kom Vuilgat, ’n opsetlike “weggooi”-teks wat allerlei sluimerende spanninge tussen die waarde van die kanonieke en die weggooibare aktiveer.

The reader encounters a beautiful edition in which the title appears in embossed letters, as on a State Bible. There’s an image of what looks like a medieval drawing of a sect in a corner of the cover. Then turn to the closing words of the book : “When they finally opened the cave, / on the third day after the stoning, / her body was gone.” Between these two master text references comes Dirty Arse, a deliberately “disposable text” that activates all sorts of dormant tensions between the value of the canonical and the throw-away.

“The reader can also just forget about deeper meanings, why not if the text does so itself sometimes, and sit back and enjoy the game.”

Die steniging het eers na Vuilgat verwys, dis tog hy wat in die hospitaal beland het nadat hy met groen appels gepeper is, maar hy ruil plekke met Stilte. En nou weet ons die liggaam wat weg is, is eintlik Stilte s’n, sy wat 64 messteke, ja, soos in ’n skaakbord, deur Vuilgat toegedien is, maar weer begin lewe het. Dit herinner natuurlik aan die Opstanding. Maar een waarin Vuilgat en Stilte (dalk twee bergies?) “nnet daardie mann en vrou wat bewe vann liefde” is.

The stoning first referred to Dirty Arse, after all it was he who ended up in hospital after being pelted with a hail of green apples, but he swaps places with Silence. And now we know the body that is missing is actually Silence’s, she who was stabbed 64 times, yes, as in a chessboard, by her lover Dirty Arse, but mysteriously come to life again. It is, of course, reminiscent of the Resurrection. But one in which Dirty Arse and Silence (perhaps they are two bergies?) are “Just that ordinary man and woman trembling with love”.

Die leser kan ook net vergeet van diepe betekenisse, waarom nie as die teks dit self soms doen, en terugsit en die spel geniet. Wat maak ’n mens van ’n sin wat Stilte as volg beskryf: “(Haar) ouer suster het nege maande gesterf voordat Stilte gebore is”. Of: “die black e i n d b e s t e m m i n g” (so, met die wit tussen die letters). ’n Beskrywing van die dood? Of van swartbewussyn (die ideologie wat ter sprake kom) as die ontwaking van die gemarginaliseerdes?

The reader can also choose to forget about deeper meanings, why not if the text does so itself sometimes, and sit back and enjoy the game. What is one to make of the sentence that describes Silence as follows: “(H)er older sister died nine months before Silence was born”. Or : “the black f i n a l d e s t i n a t i o n” (so, with the white spaces between the letters). A description of death? Or of Black Consciousness (the ideology that is discussed) as the awakening of the marginalized?

Die talle karakters en stemme en vervloeibare situasies het in plaas van ’n vermenigvuldiger-effek ’n vereenvoudigende effek, ’n sametrekking tot ’n simboliese spel. Hiervan is Vuilgat en Stilte die vernaamste, Freudiaanse argetipes bykans, iets soos Kreatiwiteit/Ekskresie en die Niet.

The numerous characters and voices and fluid situations serve to, instead of enhancing complexity, rather, induce a focusing effect, the contraction of the narrative into a symbolic game. Of these symbols, “Dirty Arse” and “Silence” are the most important, they can be read as Freudian archetypes almost, something like Creativity / Excretion and The Not.

Die teks bekla die ontoereikendheid van Engels om die werkelijkheid van Suid-Afrika te teken. Die skrywer vertaal soms direk uit sy moedertaal-Engels na Afrikaans, en die Afrikaans is ’n spel van eiesinnig gekonstrueerde demotiese vorms. Watter beter milieu as Suid Afrika om alle vastigheid in te bevraagteken?

The text laments the inadequacy of the English language to properly draw the contours of the reality of South Africa. The author sometimes translates directly from his mother tongue-English to Afrikaans, and the resulting Afrikaans is a play of idiosyncratically constructed demotic forms. What better environment than South Africa to interrogate any and all attempts at stability?