PHIWOKAZI QOZA

Choreographies of Protest Performance: 1. The Transgression of Space

Whilst doing interviews I often asked my Research Participants ‘why did you join protest?’ and quite a fair number said something to the effect that ‘I actually liked the vibe or atmosphere of protest’ and I began to think to myself that is something that is not in the literature – which is saturated with the ideation that individuals participate in activism due to an identification with the preferences and interests of an emerging group of actors or in solidarity with a pre-existing network that has resorted to a number of protest repertoires in order to make claims or demands.

This then created an opening for me to explore the atmosphere or vibe of protest… and amongst many videos and clips, I used Decolonising Wits styled as ‘Decolon I Sing: Wits’ to develop the idea of people transcending from bystanders to protest to actors in protest through song.

So, according to my thesis what occurs when protest song is belted out? In some people it creates a relation of feeling, which draws them into the atmosphere and that relation of feeling is resolved by the body in motion vis-à-vis stasis, structure. In the atmosphere of protest, the body displays and embodies a rhythm in the duration of song through which the face nods, smiles, frowns, sighs, manoeuvres the tongue to whistle, ululates, looks up and down, expresses joy and sadness, etc. The intensity moves down the body; starting with the placement of arms in an infinity cross underneath the breasts with the thumbs touching the flesh inside the elbow bend and the four fingers resting on the lower part of the upper arm, to the opening of the bind, drawing in the elbows towards the abdomen, bringing in the hands to momentarily clap in front of the body or the reaching of the hands overhead initiating or following synchronised clapping. Once overhead, the formation of fists by the hands swaying back and forth, the shifting of the body weight from the left side to the right side parallel to the fists above or the hands clapping and fingers rhythmically snapping. There is often the lowering of the upper body to give the lower body ease to waddle back and forth or to rhythmically stomp the feet in one place, followed by the lifting of the feet to a 90 degree angle to fire out knee kicks, full body jumps, and the take-off from one space to the next. A movement through which the participants march in formation while being used by the song and in turn using the song to communicate to one another. If a song is losing momentum, it is common for a participant to bolt to the front of the crowd or to the middle of the circle if the crowd is in a semi-circle or circle to lead a new song and to motion the crowd to sing their parts back to them.

I have termed this protest performance. I then argue that whereas the operation of power in society can be observed in the collective embodiment of the ideologies which keep bodies in place, the liminal and performative emergence of movement of the body creates differences in space through relations of encounter which transgress the ordering of bodies by breaking with the structure of the previous context and norms of place. The movement of the body, in the atmosphere of protest, is an event through which the body rejects the previously held image of being in space by adopting, through embodiment, a new movement image of becoming in place. Becoming protest performer is a somatic event whereupon the rhythm of song triggers a relation of feeling which is resolved by the extension of the body and is imagined as one of the primary means through which bodies are recruited into participation in activism. Thus, protest performance is in response to being affected by the atmosphere in ways which implicate sensation and movement as an affect of the encounter with socially constructed space.

In this essay, protest is presented as liminal and performative spatial transgressions which organize bodies who were ‘out of place’ in the previous spatial order via movement which negotiates difference in space via relations of encounter. To do so, it goes into the outbreak of performance to explore how the atmosphere of protest captures the spectator body and transforms it into an actor in protest. The suggestion becomes that the somatic event whereupon the rhythm of song triggers a relation of feeling, which is resolved by the extension of the body, is one of the primary means through which bodies are recruited into participating in activism. In following the participants’ felt affects, referred to as ‘feeling the vibe or atmosphere’, there was an immersion of the body into a performance of protest which beckoned the spectator of protest to respond in ways which sustained or amplified the intensity of the atmosphere found.

The Perception of Space

According to Heelan (1989: 3-7), philosophies of perception fall under three main categories; in the first, the empiricist or analytical, to perceive is to be in possession of an image that matches or mirrors physical reality; in the second, the naturalistic, the movement of the perceiver “orders the environment, accommodating to it and finding their way around it”; and in the third, the phenomenological/ hermeneutic, “a perceived object makes itself present by acting physically on the body of the perceiver”. The space, an historically white institution, in which protest emerged in 2015 had long been defined as one in which black students feel intense frustration and alienation (Koen et al.: 2006; Makobela: 2001; Matthews: 2015). In order to get a sense of how the participants of protest perceived the space in which protest emerged prior to widespread student activism in historically white institutions, participants were asked “how was your undergrad?” to which they responded:-

I found it inclusive and alienating at the same sense. Inclusive in the sense that… at the time, the social culture at Rhodes was… It did have that whole liberalness about it. And also alienating in the sense that you had to have a buy in into Rhodes culture in order to flourish and to feel the Rhodes culture – Swish

It was tough. I don’t want to lie. It was tough – Kendoll

It was very frustrating – Jaune

These students possessed an image of the historically white institution space as tough, frustrating and alienating. Traditionally, space has been viewed, in terms of its geometric properties, as an Euclidean metric area that is linear and finite dimensional (Massumi: 2002), but Lefebvre (1984: 2) proposes that space entered the realm of multiple meanings as mathematicians appropriated space and time, made them part of their domain by inventing spaces- an ‘indefinity’ of spaces: non- Euclidean spaces, curved spaces, x- dimensional spaces (even spaces with an infinity of dimensions), spaces of configuration, abstract spaces, spaces defined by deformation, transformation, by a topology.

Following which, an image of space as producing and being produced by social structures and social action emerged (Low: 2008). In the former, social structures organise relations between bodies via the norms, rules and regulations, and the laws which are expected, imposed and apply to bodies inhibiting space (Cresswell: 1996). Moreover, deviation from the conventions of place is prohibited by codes which signify that deviance is ‘out of place’ (Cresswell: 1996).

Swish, a research participant, reveals that whereas he was able to avoid “not fitting in” by performing being ‘in place’, performing being ‘in place’ did not preclude him from feeling “out of place”:

Remember when I told you that when I got to Rhodes…? Rhodes was sorted a particular manner and I could navigate this space… but in doing so you kind of go through a pathology of shifting. There is nothing more tiresome than shifting who you are in order to fit into a particular space. To fit in this space I need to strip of my essence, my blackness. I need to strip off my blackness, my essence and perform a particular Rhodes body. And that was painful. It is very painful.

The participants’ actualised place performance was an effect of his embodiment of the conventions of the place called Rhodes University. It was the only way he could accommodate to the space and find his way around it. In 2015, however, the repetition of the spatial order, for him and many others, was disrupted by the performance of protest which appeared as a transgression of space according to Van Gennep’s (Turner: 1979) ‘rites of passage’ of separation and liminality playing out as a mode of embodied activity whose spatial, temporal and symbolic “awareness” allows for dominant” social norms to be superseded, questioned, played, transformed. A mode of embodied activity that transgresses, resists, or challenges social structures. (Mckenzie, 1997: 218)

Change between before and after is the break with a prior context which functions as a decontextualization which is separate from form and routine, but at the same time, is distinguishable as a form that suspends the norm, making way for new ways of being in place (Butler, 1997: 47; 148). The space in which protest emerged is ordinarily characterised by the formal academic programme of the university which made some bodies feel out of place, but the energy of the participants in carrying out protest performance not only disrupted the structural relations of that space, but created an atmosphere of protest.

The Atmosphere of Protest

To historically situate the re-emergence of protest at Rhodes University, the participants were asked whether there was a political culture prior to the emergence of protest in March 2015, to which some of the participants responded:-

Um… no. not really. I don’t think… not that I was aware or involved. It didn’t feel like there was one – Amie.

No. not at all. There was nothing… I don’t remember – Reggie.

On campus?!? I wasn’t politically active anywhere because I had decided that any alliance-related politics are not for me – Bo

No, actually. I wasn’t politically inclined to join Sasco or Daso [student organizations], but when I got here in terms of the political climate it was virtually non-existent even though the students have SRC elections and all of that – Somila

Somila, a research participant, mentions two student organizations and the students representatives’ council (SRC) which, historically, have organized meetings and protests in South African institutions of higher education (Koen et al.: 2006). At the time of the re- emergence of protest, there was no national student union which represented student interests to the extent that NUSAS purportedly had in historically white institutions during Apartheid and none of the aforementioned student organizations initiated the protest action which the participants took part in.

In the absence of an organization of student interests, recent studies into the emotions of protest posit that certain events or situations, referred to as ‘moral shocks’, often raise a sense of outrage which is addressed via collective action (Jasper: 1998; Polletta & Jasper: 2001). At the time when research participants embarked on their first protest performance, it was widely reported that they did so in response to and under the influence of the actions of Chumani Maxwele, who threw faeces at the then statue of Cecil John Rhodes which was situated at the University of Cape Town (UCT) (Pett: 2015). The statue in question, however, had been subject to numerous acts of defacement prior to the events of March 2015 and those did not lead to wide-spread collective protest, thus a sense of outrage is not sufficient cause for collective protest action (Knoetze: 2014; Olson: 1971).

Moreover, resource mobilization scholars posit that prior to protest action, there must be the generation and adoption of an injustice frame;

a misfortune must become conceived as an injustice or a social arrangement must become viewed as unjust and mutable. In each case, a status, pattern of relationships, or a social practice is reframed as inexcusable, immoral or unjust (Snow et al.: 1986:466, 475).

At the time of the emergence of protest performance, there had been no political climate which would propel individuals to identify with the organization of student interests or sufficient outrage to bind individuals in a network of outrage, and as a result, the participants had no frame with which to “locate, perceive, identify and label” occurrences, events or situations as justifying protest action prior to its occurrence (Goffman, 1974: 21). Instead, a significant number of research participants claimed that they had been drawn to attend some of the political activities3 which occurred between 2015 to 2017 due to the atmosphere and vibe of the protest;

It’s… it’s… the atmosphere is electrifying cause you are gravitating towards other people coming together… the singing, the dancing, the demands they are making. You gravitate towards the entertainment value of being involved in the protest. Cause you see the people are chanting and singing. It’s interesting and it’s lively – Hefe.

I didn’t even know the words of the songs initially, but I wanted to join in… it’s like…

The vibe. You can feel it. It’s so fun – Asande.

It’s a lively atmosphere. So certain people gravitate towards that atmosphere – not necessarily they like what’s being said, but they just like the atmosphere around the student protest – Bo.

To understand how one feels an atmosphere, there needs to be an enquiry into how that atmosphere is constituted through an image which gives a sense of being in that atmosphere (Brennan: 2004). This calls for a protest event analysis that “goes into the moment” to reveal “the lived immediacy of experience” offered by the atmosphere of protest (Pred, 2005: 11; Thrift, 2008: 16). In approaching the atmosphere of protest, consideration is given to the idea that “protest almost always assumes an audience, onlookers for whom the events are ‘played out’” (Kershaw, 1997: 260). As such, Asande, a research participant, stated that she was initially a bystander to protest, watching the gathering of bodies and heard the tuning of protest songs and then subsequently joined protest. The interest is the encounter of the bystander body with the performance of protest which propels them to transcend from an observer to an actor in protest. Since protest is made up of singing and movement, it is what has been traditionally considered as a performance and hence it will now be imagined as protest performance.

Protest Performance

Performance is often contested for being an elusive term; for instance, “any event, action, item or behaviour can be examined ‘as’ performance” (Schechner, 1998: 361- 362). This entails both what has traditionally been thought to be performance, e.g. theatre, music, dance, art etc. which often is rehearsed for desired effect, that which is socialised through the repetition of political activities can include, but are not limited to protest, marches, rallies, meetings, occupations etc. (Billei & Cabalin, 2013; Gill & DeFronzo, 2009; Gonzalez, 2008; Tan et al, 2014; Zhao, 1998).

Since the early 1990s, performance has enjoyed a privileged status in the turn to embodiment prior to representation (Butler: 1997; Thrift, 2004, 2008). Judith Butler’s work on ‘performative behaviour’ spearheaded an engagement with performance in places and situations not traditionally marked as the performing arts such as how people play gender, heightening their constructed identity, performing slightly or radically different selves in different situations (Schechner, 1998: 361- 362)

Performance involves relations, interaction and participation between two or more bodies that constitute the performance (Fischer-Litche, 2008: 32). Whereas some literature places emphasis on the physical co-presence of bodies, it is common for some bodies to be an imagined other, contributing to the overall performance in absentia (Goffman in Burns, 1992: 112). On the one hand, performance is the art of the present; a particular constellation of forces that are ephemeral and disperse as soon as the event is consummated (Martin, 1998: 188- 189; Thrift, 2008: 136). Performance is infamous for its ephemeral status for as the body transitions between postures, there is the creation of a passive present by the future present of the next posture which becomes the vanishing point of the just occurring posture (Siegal: 1972).

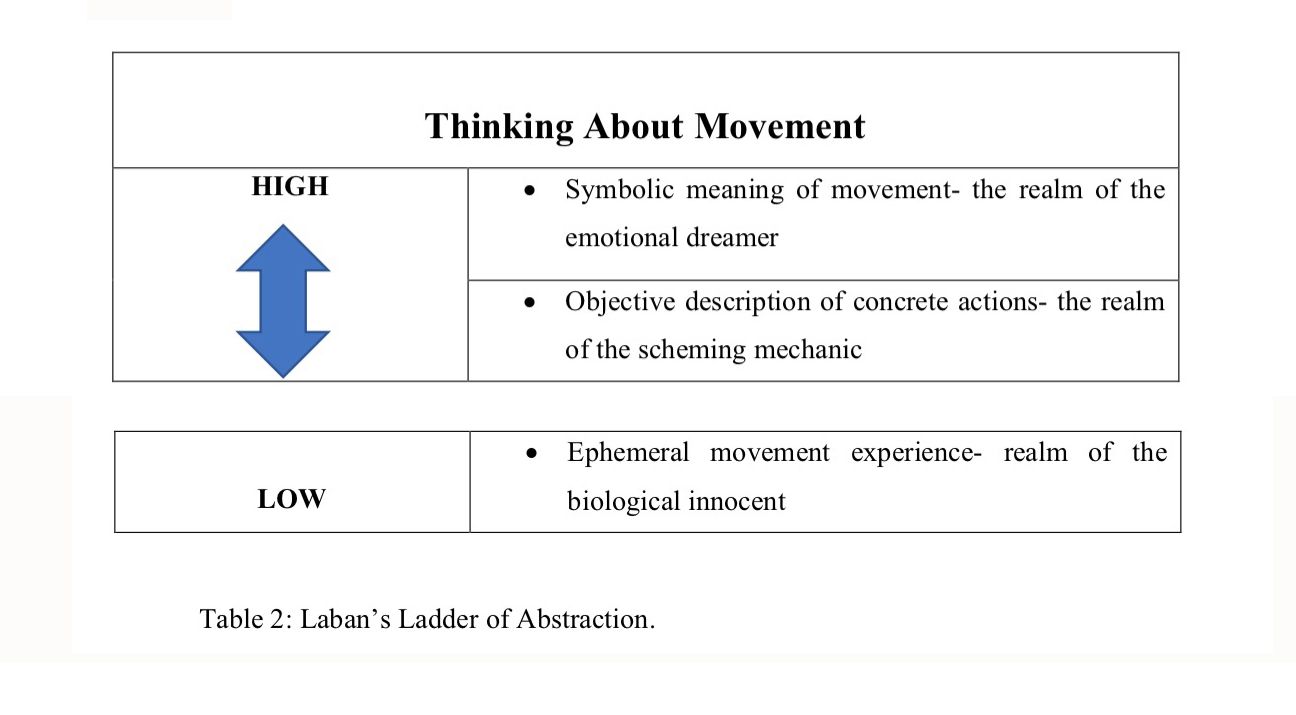

According to Laban (1974: 7), however, there is a ladder of abstraction which can be utilised to perceive movement; movement can be viewed as an ephemeral emergence of the now which is uncapturable, it can be viewed through the objective sequences it transitions through, and it can also be viewed in symbols and signs it emerges in and as creating signification in the world it leaves behind. The ladder of abstraction functions as a movement notation system enabling the possibility to read and extract meaning from movement (Moore & Yamamoto, 2012: 7;78). Below is an illustration of Laban’s ladder of abstraction taken from Moore and Yamamoto (2012):-

On the other hand, performance is liminal; it transgresses, disrupts, transforms, resists or challenges social structures in the duration of performance and long after its appearance (McKenzie, 1997: 218). The turn to embodiment latches on to performance as that which is liminal in emergence, but productive as it leaves traces in structures and beings (Rattray: 2016). Thus, the movement of the body is an event that is never consummated for it becomes how it is organising a particular constellation of forces within a specific space and time and this enables the signification of performative acts long after their immediacy (Dewsbury, 2000:473).

In order to follow the immersion of body into performance, the performance is opened up via song. The effects of song, widely referred to as music, have been researched through experiments conducted in a controlled environment or through a musical anthropology of how people use music to construct their social reality. In the former, research participants who do not perform or create music have been asked to rate the arousal, valency and dominance of short video or audio clips through observation, questionnaires and semi-structured interviews (Christensen et al.: 2016; Sokhadze: 2007). Following which, it has been argued that through contagion, imagination and expectation, “music has the potential to induce collective affective phenomenon, such as behavioural, physiological and neural changes, in large groups of people” (Christensen et al.: 2016; Scherer, 2004: 247).

How do musical effects manifest outside of controlled quantitative research experiments? One of the contributors to the Body and Society Journal proposes that listening and noticing call for “a practical methodology where sound is subject, a vehicle and a medium for thinking” and to do so, Sonic Bodies encourages a “thinking through sound” instead of “thinking about sound” (Henriques, 2011: xvii- xviii).

In the African Noise Foundation published documentary Decolonising Wits styled as ‘Decolon I Sing: Wits’, Kaganof (2015) captures a number of protest songs in duration and two will be sampled below to draw out the structure of protest song;

Caller: ‘Senzeni Na?’ (What have we done?)

Responders: ‘Senzeni Na? Senzeni Na!?’ (What have we done? What have we done?!) X4

Caller: ‘Sono Sethu… (Our only sin…)

Responders: Sono Sethu Bubu’mnyama’ (Our only sin is that we are black)

Caller: Aya’ncancazela (They are Trembling) Responders: Aya’ncancazela (They are Trembling) Caller: Aya’ncancazela (They are Trembling) Responders: Aya’ncancazela (They are Trembling)

Both Callers and Responders: Aya’ncancazela Amabhunu/Amabhulu Ayebulale uChris Hani

(The Boers who killed Chris Hani are Trembling).

Caller: Uthi’ Masixole Kanjani? (How are we supposed to forgive/ be at peace?)

Responders: Uthi’ Masixole Kanjani? (How are we supposed to be at peace?)

Both Callers and Responders: Uthi’ Masixole Kanjani Amabhunu/Amabhulu Ayebulale uChris

Hani (How are we supposed to forgive/ be at peace when the Boers killed Chris Hani?)

The above transcription illustrates the structure of protest song, and by extension its performance, is characterised by repetition. What is repeated makes it possible to compare and contrast the traction of some protest songs and not others, to evaluate the degree of intensity that carries the performance of protest song in one space and not another, to distinguish the tone used or rhythm built when particular songs are tuned and not others, and to follow schemas used to constitute the performance of protest etc. Whenever protest song is sung, it is at the discretion of its performer to select a particular chant and tempo, but most South African protest songs are short in length and have two main parts, that of a caller and that of responders (Kaganof: 2015; Mbuli: 1994; Ngema: 1992). The antiphony begins with a leading voice asking or stating something which the rest of the group repeats or confirms back to him or her (Kaganof: 2015; Mbuli: 1994; Ngema: 1992).

Although protest song is structured by the antiphony, a number of those featured in the Lee Hirsch (2003) documentary Amandla: A revolution in four part harmony state that in duration, there is no universal order of protest song and the manner in which the crowd follows or unfollows the song being led is spontaneous. The caller may employ the schema of serenade, which entices the audience and invites it to participate in the potential of song. An invitation can be accepted or rejected in a number of ways; song might be ignored, song might be followed and the audience may reject the initial caller by following a different caller which changes the song in duration. This is typical of ‘songs of persuasion’ which appeal to the listener and attracts them into their duration (Denisoff: 1966; Vail & White: 1978; Widdess: 2013).

According to participant reflections, upon hearing song there was a common ‘feeling of the atmosphere or vibe’ which propelled actors to gravitate towards the site where song was being performed. Theories of emotion would suggest that a state of knowing, such as feeling, illustrates an emotions schemata for it is only when the subject becomes aware of itself does it produce “human actuality” which is personal and biographical (Damasio in Wetherell, 2012: 35). Moreover, the process of event evaluation, through which the feeling or sensation becomes perceived, has to be checked against previous experiences and represented as the said state of knowing (Scherer, 2004: 244; Shouse: 2005: 1). Indeed, a relation of feeling speaks to how the dynamics of an event are felt and it is a perception of the atmosphere or vibe of protest (Massumi: 2002; Phillips-Silver & Trainor: 2005). What delineates feeling as an emotion, however, is when it is appraised. That is, the feeling only becomes subjective after the fact of its actualisation.

At the time of emergence, in its liminal-becoming, the feeling is not only viscerally sensed, but it opens the body to variation in its capacity or power to act and change in any direction, which is the manifestation of affect (Georgsen & Thomassen: 2017; Lobo: 2013; Massumi: 2002). The body which varies in power or capacity to act implicates an event of the somatic nervous system (motor expression in the face and body) (Massumi: 20002; Scherer: 2004). The somatic nervous system receives and relays information through exteroceptors, interoceptors & proprioceptors (Moore and Yamamoto, 2012: 13). The first, exteroceptors, receive information via the five senses of vision, hearing, smell, touch, and taste; which is passed on to the second, interoceptors to accept, ignore or modify by the third, proprioceptors, which orientate the response to be carried out as motor activity (Moore and Yamamoto, 2012: 13-14).

In those who transcend from a spectator of the performance to an actor in the performance, the imperceptible rhythm of song is received by distant senses of hearing and oftentimes vision, which is then resolved in ways that increase the body’s capacity to act. The resolution of imperceptible forces and intensities can show forth as …automatic reactions, non-conscious, never to be conscious remainders, outside of expectation and adaptation, as disconnected from meaningful sequencing, from narration. [They are] narratively de-localized, spreading over the generalized body surface (Massumi, 1995: 85).

The body displays and embodies a rhythm in the duration of song through which the face nods, smiles, frowns, sighs, manoeuvres the tongue to whistle, ululates, looks up and down, expresses joy and sadness, etc. The intensity moves down the body; starting with the placement of arms in an infinity cross underneath the breasts with the thumbs touching the flesh inside the elbow bend and the four fingers resting on the lower part of the upper arm, to the opening of the bind, drawing in the elbows towards the abdomen, bringing in the hands to momentarily clap in front of the body or the reaching of the hands overhead initiating or following synchronised clapping. Once overhead, the formation of fists by the hands swaying back and forth, the shifting of the body weight from the left side to the right side parallel to the fists above or the hands clapping and fingers rhythmically snapping. There is often the lowering of the upper body to give the lower body ease to waddle back and forth or to rhythmically stomp the feet in one place, followed by the lifting of the feet to a 90 degree angle to fire out knee kicks, full body jumps, and the take-off from one space to the next. A movement through which the participants march in formation while being used by the song and in turn using the song to communicate to one another. If song is losing momentum, it is common for a participant to bolt to the front of the crowd or to the middle of the circle if the crowd is in a semi-circle or circle to lead a new song and to motion the crowd to sing their parts back to them (Ibid.).

Conclusion

Whereas the operation of power in society can be observed in the collective embodiment of the ideologies which keep bodies in place, the liminal and performative emergence of movement of the body creates difference in space through relations of encounter which transgress the ordering of bodies by breaking with the structure of the previous context and norms of place. The movement of the body, in the atmosphere of protest, is an event through which the body rejects the previously held image of being in space by adopting, through embodiment, a new movement image of becoming in place. Becoming protest performer is a somatic event whereupon the rhythm of song triggers a relation of feeling which is resolved by the extension of the body and is imagined, in this chapter, as one of the primary means through which bodies are recruited into participation in activism. Thus, protest performance is in response to being affected by the atmosphere in ways which implicate sensation and movement as an effect of the encounter with socially constructed space.