NIKLAS ZIMMER

Interspeller (some B-sides)

Niklas Zimmer & James Webb – Post

1980 (Maseru, Lesotho): I’m five or six years old, my mother has just put me to bed. It’s late in the evening, we have visitors. From under the blankets in my cold room with its single-glazed window panes facing the moonlit winter tree, I can hear music, talking, laughing. Across the hall, the adults are gathered in the lounge around the stereo speakers, next to the fire glowing in the Jetmaster. The sound of jazz and African politics. Years later, I learn that the records my father was playing for his colleagues and friends on those nights had been bought ‘overseas’ (i.e. Europe or the States) because they were banned in South Africa at the time. Huddling, harking – ‘We Want Miles,’ cans of Lion lager, cigarettes without filter – a lively, joyful togetherness. During the day I am always outside, whether the huge open sky is allowing the sun to melt the tar of the main road, or dark banks of clouds to spit hailstones on our lawn. My friends and I climb the big willow trees hanging over the orange mud banks of the Caledon. I smell the fresh bark and feel the swaying of the big branches over the thick water swirling below. My world is what is immediately around me. I fish for crabs under a rock at the dam, I see them, but they never take my bait. When I see a TV for the first time at my friends’ house, I run home and tell my parents all about this amazing fast car that can drive straight through walls without even getting scratched!

Niklas Zimmer & Julia Raynham – Aluminium Memories

1982 (Bergheim, Germany): The school building is tall, with stairs inside, so different from the spread-out bungalows of Maseru Prep. The kids aren’t wearing a uniform, just running around and screaming. Nobody gathers or walks in a line. I am bad at maths, the numbers are all spoken the wrong way around. Even though these teachers don’t hit you with a ruler on the outstretched hand for being naughty, I miss being able to know for sure what it is that I am supposed to do. I miss my friends, skidding and ramping our bicycles on the dusty dirt roads. All the streets are tarred and there are no kids playing outside. I spend a lot of time drawing at a desk in my room – awkward, naked stick figures in pink felt-tip pen because that’s what I imagine everyone here looks like under all their clothes, including the girl in my road that sometimes lets me visit her at her home. I fill the wallpapered, carpeted silence in my room playing back cassettes on a small silver Panasonic stereo radio cassette recorder, classic German children’s stories published by Deutsche Grammophon that my mother has bought from the bookstore in town. When I flip the blue switch away from ‘cass’ to AM or FM and carefully turn the dial upward or downwards to get a clear signal, the pop music coming from the radio feels harsh and cold, like crashing and shouting. I don’t remember the moment of being torn away from everything and everyone that I know and love, only the feeling of endlessly waiting for the loneliness to stop. My parents had driven me to the grassy Moshoeshoe airport without any explanation. No ritual, no goodbyes from my friends. It was what they had learned growing up in the wreckage of WW2: no use in looking back.

Niklas Zimmer & Derek Gripper – Still

1984 (Bergheim, Germany): I have made a friend. He lives in town, almost an hour’s drive away from our house. We have weekend sleepovers, drawing comics together on the floor. We discover that by recording onto a cassette with intact tabs in the top of the case, my Panasonic can be used to create ‘radio plays’. We spend a year filling two 90-minute tapes with recordings of humorous sketches about monsters, humans and machines, both scripted and improvised. To make the often totally nonsensical stories more realistic, we enlist items around us to serve as (unconvincing) sound effects – including of course Lego castles and spaceships being viciously destroyed (after hours of careful construction). Most scenes end with the sounds of our own whooping and giggling. In order to advance or reverse to the correct position for re-doing a section, we make use of the little counter constructed out of three rotating wheels (only lightly pressing down the FFW and REV buttons makes it easier). Eventually, we attain magically precise tape positioning skills with two-finger button control. On this B-side, being 9 is sipping hot cocoa in blanket forts with my one friend, and making ‘radio’ skits which nobody ever will listen to. When my father is home from work for the weekend, we watch live jazz on television late on Friday nights. Music is for active listening only. The only exception is Sunday mornings, when the Köln Concert LP plays while we eat a ‘good’ breakfast, bacon and eggs, and orange juice. The Green party gets into parliament.

Niklas Zimmer & Brydon Bolton – Nocturne

1986 (Himberg, Germany): We have moved into a freestanding house in a different country village, and I start going to high school. The ‘soft start’ staccato of my little Braun travel alarm in the darkness of my bedroom every morning. A rushed breakfast at the little kitchen table sitting between my parents. The faint voice of the newsreader jabbering through the aromatic mist around the burbling coffee machine. Numb comforts that precede the walk to the bus station, the half hour of mutely swaying from the rails or handles in the crowded school bus. Dodging the routine cruelties of the schoolyard pack. In the afternoon, I have hobbies to keep me company: cycling on my GT Timberline All Terra (with 21 gears!) through the surrounding woods, taking photos of the rocky, tree-topped hills and the horses on the meadows, immersed in the golden bloom of a summer evening, or through the flat greys of a snowy winter morning, experimenting with the effects of chromogenic Ilford XP-2 film with my mother’s old Canon FT QL 35mm SLR (with the lovely FD 50mm f/1.8 lens). The choir I sing in goes on a tour of Moscow, St Petersburg, East Berlin and Leipzig. I take photos of poor children playing in the empty streets, cement walls still pockmarked from the impact of shells from 40 years ago, the odd little plastic cars, the huge old government buildings and boulevards, everything faded and crumbling into muted greens and browns of chipped mosaic and cracked cast iron. On one of the long bus journeys, I get to plug my headphones into a friend’s (all-metal!) WM-DD2 Walkman (with two headphone outputs and autoreverse!) and hear Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway for the first time. Being one of a small handful of boys surrounded by almost fifty teenage girls, singing Händel, Mozart and Orff in old TV studios, churches and monuments behind the iron curtain, music now has an erotic dimension that finds its only relief in more. Singing, playing, listening more, I want to get my hands on all of its devices. I yearn to feel it, to hold it, to make it.

Niklas Zimmer & Ben Amato – Heatseeker

1988 (Himberg, Germany): I spend a couple of hours every day practising the piano (Bach, Czerny and Debussy). I have no talent, but the difficulties of fingering and of bringing out different voices offer a complete mental escape. It’s painful but also addictive. Apart from attending choir practice and piano lessons in the nearby villages, at home I now get to operate the stereo system. Listening for countless hours on the Infinity speakers, or on my father’s old pair of closed, white Pioneer SE-30 stereo headphones (that always leave behind little black flecks of plastic on the ears), I discover recorded music from all over the world. There is no context in this activity. I don’t know anything about genres, other than perhaps some unconscious scraps of pedestrian snobbery around ‘classical vs pop’. Each record I pick from the shelf is a new sonic exhibition of works by artists from all over humanity’s times and places, and each one fills me up with notions and sensations that I sense are otherwise somehow absent from my life. Literally hundreds of records with well-worn covers, from a lifetime of listening before me that I give no thought to at all … Santana’s Abraxas, Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. I sit for hours every week on the cold marble step next to the Hi-Fi set, listening, selecting and arranging the ‘best’ pieces into some kind of 90-minute abstract narrative onto cassette. Hunched over artfully decorating the blank, serrated covers, I faithfully copy out the wonderfully strange titles, album and artist names with a fine liner. Everything has to be handled and adjusted carefully: pulling the vinyl record from its sleeve while only touching the edge; lowering the diamond needle in the Shure M91 cartridge on the SME 3009 arm slowly into the groove, after first giving the heavy platter of the Thorens TD 125 MK II turntable a gentle push start; setting the push-buttons and click-wheels on the Onkyo A-8150 stereo amplifier to route the signal correctly; trimming the input on the L/R faders on the Nakamichi BX125E tape deck while keeping it in ‘record pause’ mode, after advancing the tape for a few seconds, until the signal is neither too hot nor too weak to be faithfully recorded onto a fresh Maxell XLII-S chrome cassette (or on rare occasions, when I have pocket money to spare, even one of the heavy, rubbery MX metal ones). Once every other week, I post the mixtape to my new best friend in the city, whom I met at a youth camp. The tape is generally accompanied by a jumbo print of my latest best photo, and a few pages of thoughts and news about music and girls, either handwritten (ALL CAPS, in sepia ink) or typed (not all caps) on my mother’s old Olympia SM3. I sometimes give him a phone call on our avocado green, rotary dial telephone, while sitting on the staircase in the hall. We can never keep the line occupied for long because he has siblings, and his mother works from home for Amnesty International. Magnetic tape, drug store photo prints, airmail paper, and machine-printed postage stamps (because they’re much cooler) are the first materials of our friendship. A year or two later, these are joined by alcohol, bicycles and roll-up tobacco (Javaanse Jongens), when we ride on weekends from one teenage house party to the next, getting as drunk as possible, through the misty nights, putting on LPs by The Police, REM, Talking Heads and Frank Zappa (depending on our poor estimation of which songs won’t chase the girls into the other room). My greatest LP love at the moment is the Beatles’ Rubber Soul that I recently bought (which makes me ache to experience the 1960s, just for a day), but I’ve learnt to keep that a secret. Nobody is into that cheesy old rock their parents used to like. As the nameless Heimweh inside me begins to move down from my heart to my groin, I wake up to the fact that scores of villages spread out over the hills of the Siebengebirge are teeming with girls my age, all busy growing up right now like me in their own little bedrooms. Except theirs smell different and are covered in posters of horses and rock bands. ‘Petting’ in the cultural wake of ‘Posers’ and ‘Poppers’ always has to happen to a soundtrack, and while for one girl it’s whiny, slow Michael Jackson playing softly from beyond the pillows, for the other, it’s Metallica’s Ride the Lightning on loud (with ‘loudness’ switched on), until her mother comes in and finds us half naked. The total aesthetic alienation makes perfect sense while exploring the equally foreign terrain of their bodies. At school, I get labelled as a ‘Goth’ because I only wear black, I’m pale and I smoke. In order to understand this new label that the bullies are using to frame my otherness with, to affirm my status as an outsider, I buy a couple of albums by Bauhaus and Joy Division. But I don’t get this music at all – it’s derivative, self-indulgent, dull, bleak and repetitive. The idea of large quantities of young people subscribing to this artless trash and it being a whole, profitable subculture literally scares me. Despite the fact that the two records cost me as much as 10 fresh Maxells, none of the songs make it onto a mixtape of mine.

Niklas Zimmer & Mark Odonovan – Unrest

1990 (Himberg, Germany): On a Saturday morning at a flea market in Bonn, on a whim and for the price of a Döner Kebab and a Coke, I buy an old Philips N4308 Reel to Reel tape recorder with a couple of shopping bags full of dusty ½-inch tapes. That night, once I have learned by trial and error how to thread and playback a tape, my room suddenly turns into a spaceship. My skin is literally tingling with fear at the nameless sounds coming out of the built-in speaker. In the following nights, I lie back in my Thai Papasan chair, dead still, being bathed in the strangest music (or whatever some of what I am hearing should be called). I am not even always sure whether I have selected the correct playback speed. There are no labels, no pictures, no titles, no lyrics … no words to contain the experience, no essays, notes, warnings even! [To this day, I encounter fragments of what I first hear on these nights: Billy Cobham’s Spectrum, Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel, Kraftwerk, Woob, Tangerine Dream … but many of the electro-acoustic, experimental soundscapes have remained unidentified, perhaps some were original]. It feels like my ears have only now really started opening and connecting to my brain. The countless metres of smooth, grey-brown tape being pulled through the electric machine reveal a hidden universe of sound and spool out a promise of endless discovery and fulfilment. Again, I disregard completely the collector, the intermediary in this discovery. As my dull inner yearnings are unmuted, awakened and placated by the music and the sound, I regain a sense of connectedness to beautiful strange humans, somewhere out there in the world.

Niklas Zimmer & Waldemar van Wyk – Shining

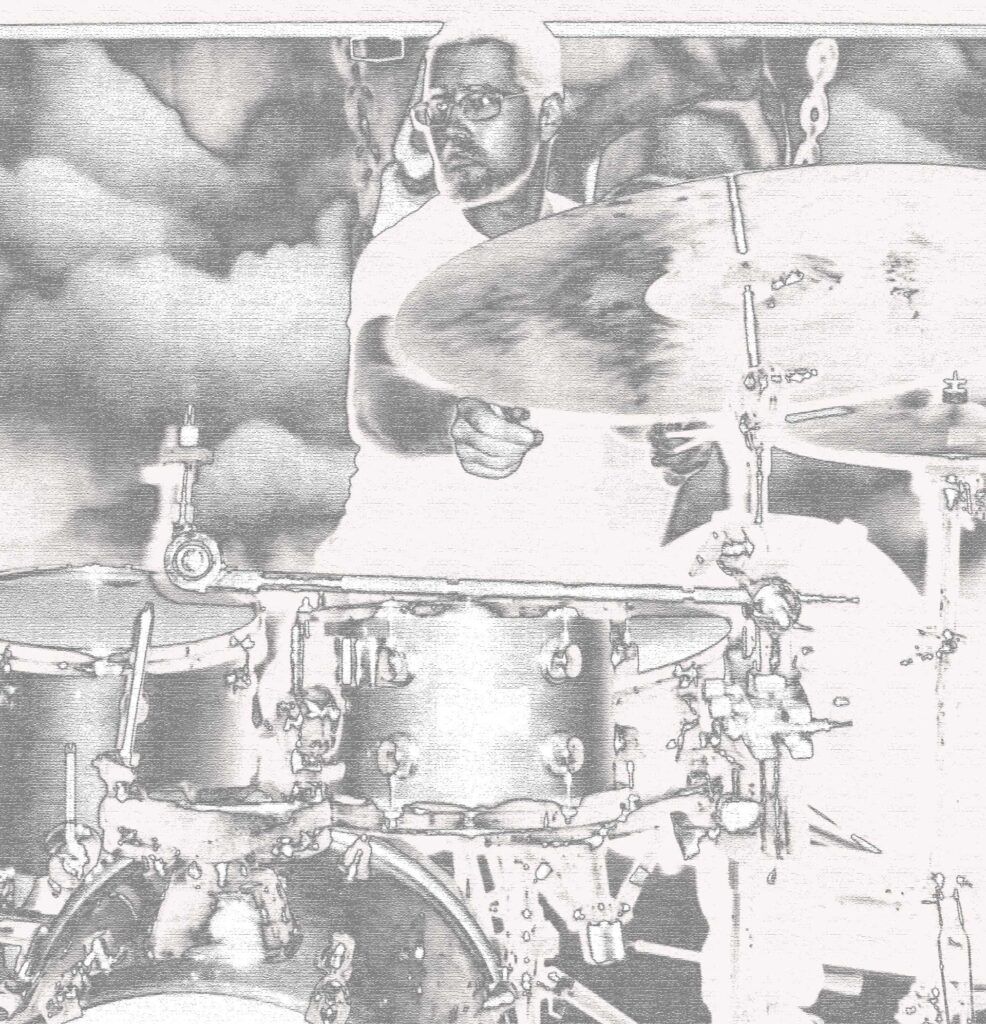

1992 (Himberg, Germany): I have come to an agreement with my teacher, the local church organist, that I also get to practise some Chick Corea and Bill Evans. He lends me an old Arp Odyssey synthesiser pulled down from his attic, together with a big old amp (with a spooky spring reverb inside it). Once everything is hooked up and powered on, it’s fun manipulating the sound via the many little, multi-coloured faders, for example repeating the same pattern with my right while pushing up the ‘Portamento’ with my left, and hearing what happens. But eventually the limitations of the narrow keyboard with fiddly plastic keys, of which you must only push down one or two at a time, amounts to feeling like a waste of time. Also, the heated-up dust stinks. I have started teaching myself to play the drums, which I play in the ‘Jazz AG’ (Arbeitsgemeinschaft = working group) at school. Our little octet practices hard, pieces like Blue Monk, Hit the Road Jack, I Feel the Earth Move, entertainment for pensioners and parents. The band is a refuge from all the jocks around us, as well as – even worse – those that believe themselves to be ‘alternative’ because they consume exactly what is being marketed to our population segment: Die Toten Hosen, Die Ärzte, or – even worse – Guns ‘N Roses. Our music teacher and band leader arranges a lot of gigs for us, at local cafes, the opening of a bridge or a library in town, and so on. We go away on weekends to rehearse. The pianist, Andrea, whom everyone calls ‘Mausi’ is my first big love. She lives down the road from me, and we divide our time between making love and making music. I teach myself to play some electric bass and saxophone, too – on cheap old musical instruments that are easy to find in the local second-hand paper, often for the price of picking it up yourself or ‘what have you.’ I start using a Tascam 424 PortaStudio and a pair of Sennheiser MD421 microphones borrowed from our teacher to make recordings of my ‘experimental’ compositions, inspired by the minimal music and jazz I currently revere, like Steve Reich and McCoy Tyner. Of course nothing ever ends up sounding the way I imagine while clumsily sketching basic melodies and rhythmic patterns on earnest paper notations. I am hopeful that through hours of constant daily repetition, my theoretical ignorance and lack of manual skill will eventually give way to more interesting compositions and more lively playing. But instead of spending any time actually studying harmony, I am waging a constant battle against tape wear. Over the course of constructing a piece, the first tracks are always already drowning in the rising hiss, especially once I start bouncing them down. This only increases the sombre, hermetic mood overall, sort of like a colour filter or solarisation on a photograph. Initially, I have no master recorder to mix down to [eventually I get my hands on a Philips DCC-170, and then a Tascam DA-20], so I keep the multi-track tapes and just make individual tape copies for the small handful of friends that might care to listen. These daily recording journeys become all-consuming, and I hardly do any work for school, except for some writing and painting in German and Art. My parents occasionally take me to the Philharmonic in Cologne. We go to see some of the greats whose many records are on the shelves at home – the incredibly virtuoso Chick Corea with his Akoustic and Elektric Bands, Pat Metheny solo with a huge box of pedals and cables on the floor [yet to little effect], and my one and only ‘idol,’ Miles Davis, with a band that is fierce, liquid fire. We hear The Alban Berg quartet perform all of Bartok’s String Quartets over three days, and we attend the premiere of a composition by John Cage for large orchestra. Witnessing the sheer mastery in these performances brings it home to me that I will never be skilled enough to compete and survive in the world of live music. I sense that any contribution or participation from me will by default be remote, marginal and unpopular. In the meantime, my ensemble of old and odd instruments has taken over half of the lounge, and I spend my day in loop-record mode, endlessly repeating takes… rewind, hit record, run around the drumset or back to the piano, put the headphones on, listen for the last clicks of the pre-recorded metronome and dive in for another attempt at a faultless two-, five-, eight-minute single take, ears always pricked (have to keep the headphone volume low to avoid bleed) for those passages with slight changes in speed, and straining to keep the dynamics as even as possible (not having any pre-amps or processors in the ‘chain’), hoping that no car will hoot outside and that the telephone won’t ring. As the end of high school slowly approaches, my ongoing disinterest in most subjects, along with my amateurish escapades into recording music, but most of all my relationship present as increasingly worrying distractions. This does not deter Mausi and me, of course – we are Gottfried Keller’s Village Romeo and Juliet. One afternoon, she plays me one of the first CDs she has bought: Tom Waits’ Rain Dogs. The title track embeds itself directly and permanently in my heart, although I don’t really understand the lyrics.

1994 (Himberg, Germany): Mausi moves out of her parents’ home into a student digs in Bonn. A few weeks later, after not being able to get her on the phone for two nights in a row, I alert her father and we drive to Bonn together. We break down the door to her room, where she is lying in her bed, cold and blue in the face. The autopsy reveals that she likely died in her sleep from a heart condition. In a sleepless haze of suicidal thoughts, I stop trying to make things work at school and start living each day as my last. At home much less now, hitching rides to town to hang out and go out for days and nights on end with a group of friends that are all busy wasting their youth in an unbroken string of parties crisscrossing the city from under the bridges over the Rhine to the empty homes of parents away on holiday. Amongst Antifa sympathisers, having a defined relationship status is at best uncool, and the soundtrack to our misdemeanours ranges quite narrowly from old punk to the latest hardcore and grunge.

Not being alienated can feel alienating, too.

Somewhere in the months of late nights fuelled by booze and cigarettes, loud music and sex without love, I start finding the dreamless sleep I seek. As we make our way through the city streets, riding trains, shacking up for weekend getaways in holiday homes across the border, I document our burning fall into beautiful self-destruction with the camera. Taking their portraits is an organic extension of our love as a group and a celebration of the tenderness hidden inside all the noise. In this period, I get to go twice on a ten-day ‘Jazz & Rock in process’ workshop at Akademie Remscheid (with many cool teachers, including Udo Dahmen, Peter Wölpl, T. M. Stevens and many more). On a secret outing, Willi Kellers takes me along to visit Peter Kowald in the nearby Wuppertal. Kowald lives with his double bass and a huge bicycle in a largely empty loft, which is like the home I wish I could choose for myself. In the following months, I often visit him there, ‘am Ort’. Occasionally, I get to join the Ort Ensemble (Cuts, 1995), and also play some free improvisation during the intermission of a Pina Bausch production. I am there to listen and learn.

Peter’s ‘Ort’ is a space for artists, musicians, dancers, poets and painters from all over the world (as well as some locals). In the ‘rehearsals’ and during the performances I become witness to beautiful ways in which free improvisation (nobody really talks about Jazz) can be used to sound out the depth of each present moment; ways of letting go of the expectations inherent in genres and styles – limiting judgements, ‘right’ and ‘wrong.’ On Saturdays, when everyone helps to set out trestle tables and folding chairs in the studio, the performance begins with Kowald’s solo ‘trance,’ bellowing out a deep, overtone chant while bowing and plucking with both hands all four strings of his double bass at once, melting down the discord of artifice in the world and channelling it into a rebirth of raw sound energy.

Niklas Zimmer & Thain Torres – Ellipse

1996 (Cape Town, South Africa): In my first year of studying Fine Art at the University of Cape Town I live in digs with a DJ who introduces me to the world of electronic dance music. CDs and LPs scattered everywhere play into the night – brand new releases of Ambient, Drum and Bass, Jungle and Trip Hop from London, casually mixed together at different speeds and in different directions with ‘retro’ finds from local junk stores, like 70s Easy listening or educational spoken word stuff. Cold breakbeats by Roni Size or Squarepusher cutting through nameless schmalz designed for suburban cocktail lounges; a Learn Xhosa LP playing backwards over a white label (actually Autechre) single playing at 33⅓ rpm. Many of us students feel that there is so much not happening; so much untapped, potential synergy between the worlds of fine art, fashion, music, drama and dance. Most of us learned in art history at school about DADA, installation and performance art, but of course our actual, present-day sense of ‘(visual) culture’ is informed by movies, magazines and MTV, and not by what’s for sale at the small handful of galleries and museums in town – which are concerned with peddling meaningless kitsch as <insert: authentic/traditional/etc.> ‘African Art‘ to tourists. In the apolitical lull after the recent waves of ‘struggle art’ and ‘identity art,’ most symbolisms have gone cold, and the focus is now on the medium and on space/place. The whimsy of détournement has a rebirth, as we experiment with collaboratively producing works that are site-specific/interactive/multimedia. Much of this happens ‘after hours’ through friendships and relationships with drama students, using borrowed AV gear, in unoccupied buildings in the CBD. It’s the beginning of the Sluice collective, The Public Eye and District Six festivals, Night Vision, and the Pickle Parties at Long Kloof Studios. It was also the time of Raves popping up in the middle of nowhere at night. Chill Out lounges, Ecstasy, the first cell phones, emoticons… and the School of Fine Art continues to teach design, drawing, painting, photography, printmaking and sculpture – Eurocentric and traditional. While the lecturers like to tell us to ‘push’ the work, really where they are coming from is a modernist, formal aesthetic. Actually, they are completely disinterested in the hyper-medial work many of us are yearning to get involved in making. The department is not encouraging of us working across disciplines (let alone faculties!). Digital glitch culture is happening all over the world, Björk releases Post, Trip Hop is top-10 radio mainstream, and postmodernism is taught in the English department, but most of us haven’t even touched a computer mouse yet! A friend of mine in the flat above our digs ditches studying jazz guitar to start building websites for big corporates and makes too much money much too fast – while on campus the only person using a computer (reluctantly!) is the school secretary. I realise that

I am not only living in a different country but also in a different historical present.

eMail takes place in an ‘iCafe’ with four PCs on Long Street. In the English course where we read Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Chinua Achebe and discuss white privilege, I come to realise that I am basically criminally naïve. While I slowly come to understand art as a social activity, and its materials as comprising a self-conscious play with expectations, gaps and tensions, our curriculum doesn’t seem to provide for ways of working that feel relevant to our time and place at all. Beyond the boring confines of our little academic art world, web and print designers all over town are using Apple Macs and running (ripped versions of) Photoshop, Quark and Dreamweaver to produce basically all of the things we look at and listen to – on and off campus. And they are making a living doing it. Which means they can also get their hands on, install and play around with tools like Reason, Acid, Reaktor and SuperCollider. Studying ‘Fine’ Art – which the lecturers are so fond of saying “can’t be taught” – feels like a fine waste of time! I’m playing drums in a 4-piece band that never quite makes it from the rehearsal space (a gallery above Outlaw Records in Castle street) to the stage. We are gunning hard for a cut-and-paste, deconstructionist aesthetic. But, listening back to our live recordings on MiniDisc once a week, it seems evident that repetitive combinations of breakbeats, bass drones, floaty guitar riffs and random vocal phrases actually do sound better when they are recycled by machines with cold precision. Between Arvo Pärt, Radiohead, John Zorn and Red Snapper everything is becoming accessible, and the field of play seems to be shrinking.

Niklas Zimmer & Deborah Poynton – Ivory Tower

1998 (Cape Town, South Africa): The inside and the outside are starting to catch up to one another – being 22 can do that to you. I am in the third year of my honours degree, majoring in sculpture. I just got married, why not, and am living with my wife in an old victorian house in Observatory. In the cupboard under the telephone is her record player and some LPs, from her ex – Charles Mingus, Tuck and Patti and Funky Porcini. Again, a collection that archives something to be elided. What do we use to get us closer? She carries on living in her box of paints, we walk the dogs by the river, and I continue to rock up on campus on my Suzuki DR500 scrambler, with office hour regularity. I finally get my hands on some gear that allows me to sample and loop with, and to bounce tracks losslessly. My sampler is a used Kurzweil K2000 synthesizer found via the CapeAds. I feed it with my ENG-style MiniDisc recordings. I capture these ‘found’ sounds like photographs, audio-snapshots of my motorbike’s single cylinder idling erratically, our cats’ circular-breathing purring, the rain’s wild polyrhythm on the corrugated iron roof … all of which I can now manipulate, arrange and play back via the keyboard! It’s a puzzling, immersive and all-consuming activity. While installing the expansion sampling unit, for which I have to cut out a part of the plastic casing with a carpet knife, the blade slips and I slice open my hand and wrist like a fisherman gutting his catch. I don’t want to go to the hospital for stitches, and ask my wife to just tape the flesh together with a long piece of plaster. The resulting hypertrophic scar is a sign of how unfinished I will always be in this life. My recording setup now also includes an Alesis Studio 24 mixer (with two stereo subgroups!) and a Fostex DMT8 VL digital multitrack hard disc recorder. I have no critical understanding of how tightly preconditioned the road I’m going down here actually is. Even though sampling has now become the asininely ubiquitous aesthetic of virtually all radio pop, the possibilities of experimenting with concrete sounds as instrumentation – and vice versa – remain exciting in the home studio. I produce a run of 100 CD-Rs of my first album, The Magic Spaces [if anyone has a working copy, please get in touch]. I lose the appetite for sampling already published material quite quickly after spending several weeks creating a whole track constructed around samples I made from Meredith Monk’s Dolmen Music (another one of my parent’s old LPs), and then hearing a track on DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing with samples from the same album. It seems that while artists are now becoming creatives churning out recognisable and reproducible product, Industry always precedes, and Capitalism wins every Culture War.

Niklas Zimmer & Adam Lieber – Twinkly

2000 (Sedgefield, South Africa): We have moved to the country, a remote hill-top house half an hour’s drive away from a small sea-side town. With chipboard and carpet, I convert an old, brick outbuilding into Upland Studio. Into this tranquil wilderness, my son is born. His mother and I, our studios across the garden from each other, slip into the A-type neurosis of ‘50-50’ time looking after the baby. It has become affordable to record sound directly to a PC, because the read/write speed bottleneck of built-in IDE drives (vs external SCSI ones) is basically gone. With our G3 PowerMac, a cheap sound card, some old mics and a copy of Cubase, I get to work on Conference (UP01). Most of the day is spent playing and recording drums and piano. Later, I edit reusable sections, burn sets of separates to several CD-Rs and post them to my collaborators. As I start receiving their CD-Rs in return into our postbox in town, the editing work intensifies, but also my playing opens up with the needs of each composition. It’s like a year-long rehearsal, and I learn a lot of new things. Music made in bits and pieces, by adding and taking away, in the mode of a traditional artwork. We know what we know. Eventually, 1000 copies are produced, and we give a long, freely improvised launch concert at the Armchair Theatre in Observatory. Conference contributors that have never met before go on as performers – actor, bassist, DJ, drummer, and so on. I honestly don’t understand the reluctance of some to do this. Someone from eTV is there to cover it. All the money made at the door goes to the sound engineer [I have still not received his recordings]. The album gets some lukewarm reviews in a couple of magazines and blogs, and a couple of agents get it placed it in some stores (although I never did get a barcode), but it seems the project is lost between the requirements of ‘serious’ music for the self-conscious historicities of a single author on the one side, and on the other those of contemporary popular music for catchy riffs and danceable beats. A sense of failure, the meaning of sour grapes, and reality checks in: you’d be better off aspiring to other people’s clichés; making things complicated just means you’re hiding in parentheses.

Niklas Zimmer & Nicholas Birkby – Idle Hands

2004 (Strauscheid, Germany): The time for playing music has vanished. I am still studying, but am also working as an archivist at the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany in Bonn. I sell my dearly beloved Yamaha 9000 recording custom drums and C2 baby grand piano. For what money I get, I buy a PowerBook G4 and a used Herman Miller Aeron chair. The ongoing optimisation of sound reproduction is just one of the myriad side effects of an ongoing, modernist class struggle, and my creative journey in music has been a common atom in the cosmic clouds gathering towards the singularity of total, global datafication. I have just been a monkey jabbing at the infinite typewriter. Now that I am largely screenbound, I join the faceless ranks of workers ingesting and disseminating standardised information in emails, word documents and archival management software.

2006 – 2020 (Cape Town, South Africa): Do not affront or confront the elite that feeds you; Divorce; Amputation of familiar souls; Dissociation; New love; Acceptance; A third son; Discord; Just google it; There is no resisting or understanding the formless void created by humanity going online; Facebook; You are collaged and constructed from copies and quotations; Freelance; This is only a quasi-’Global South;’ Work; Photography; Humans broken on the digital wheel, we are samples fed to a ceaselessly self-reproducing maelstrom of products and byproducts, a ruinous, plastic wonderland; img016.tif; 2009-12-12_Dada South; 2010-03-04Moving house; Work; Burnout; Work; Covid-19; A few days spent working in the garden, from inside the house, the Köln Concert is playing on YouTube.