These notes, which deal with the Paris arcades, were begun under the open sky—a cloudless blue which arced over the foliage—and yet are covered with centuries of dust from millions of leaves through which have blown the fresh breeze of diligence, the measured breath of the researcher, the squalls of youthful zeal, and the idle gusts of curiosity. For the painted summer sky that peers down from arcades in the reading room of the Paris National Library has stretched its dreamy, unlit ceiling over them.

Walter Benjamin[1]Walter Benjamin, “N [Re The Theory of Knowledge, Theory of Progress]” in Benjamin: Philosophy, Aesthetics, History, trans. Richard Sieburth, ed. Gary Smith (Chicago, 1983), p. 44.

When I was younger, I was talismanically inspired by these lines near the opening of Walter Benjamin’s Convolute N. The passage concerns his place of work, specifically the ceiling with “the painted summer sky.” I didn’t know then why I was so smitten. But now I do (fig. 1).

FIGURE 1. My drawing of the library.

Let me start at the beginning.

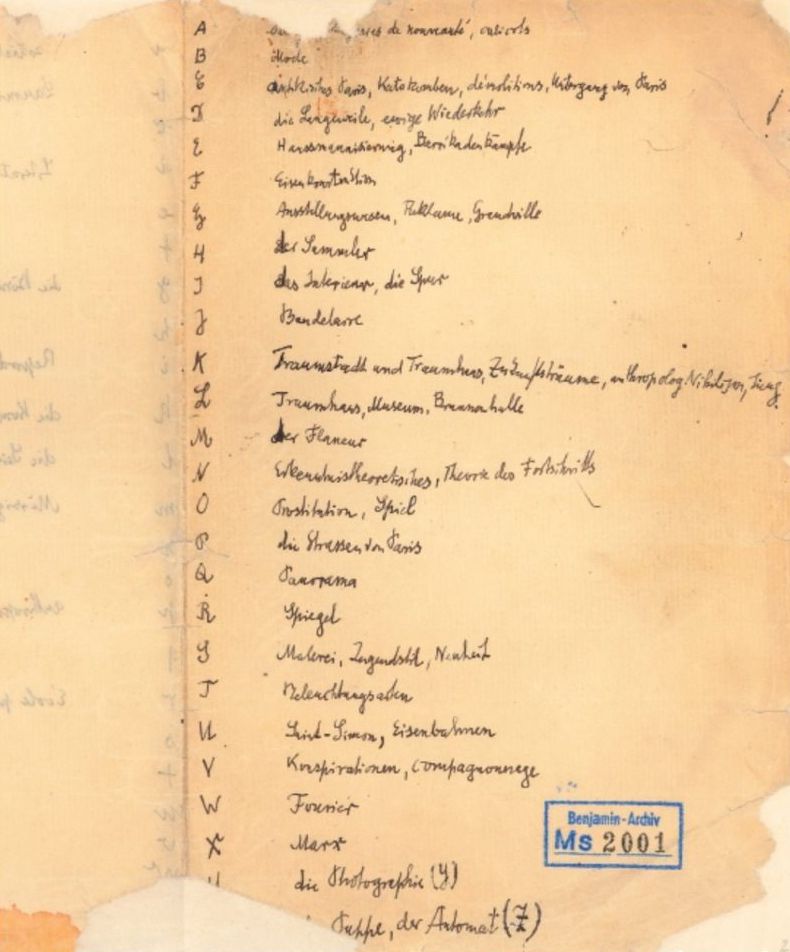

First there is the German name itself, Konvolut N, a strange and wonderful title especially for the non-German ear, straight out of J. R. R. Tolkien, James Bond, and Alan Turing’s code cracking. Even the English equivalent has a remote and magical ring to it. “Convolute”? What is that? A password for the initiated? Much better than file.

Actually, there are two names. The N refers to a file designation, like a number, while the name proper, referring to its contents, is “The Theory of Knowledge, Theory of Progress.” Within each file, such as N, each note is separated from the next and receives its distinctive number such as “N7,1,” “N7,2,” running to “N7,7” then jumping to “N7a,1” running through to “N7a8.”[2]See Benjamin, “N,” in The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge, Mass., 1999), pp. 456–88; hereafter abbreviated “N.”

This is more than numbering. The numbers seem more like the broken twigs in the forest that mark the passage of someone who has lost their way or is fearful of such. One could go further with this thought; perhaps one has to get lost in order to reach the promised land? Didn’t Benjamin himself say that the best way to know a city is to get lost in it?

It may seem a rather eccentric manner of arranging materials, but it makes sense as a working document and certainly adds to the allure of reading it as a book, or should I say a quasi book because it is more like a filing cabinet. At times it can seem like you are right there in the library watching and participating in the writing of each note wondering where the hell it’s all going, but who cares—we’re all in for the ride.

You can see the researcher sinking deeper and deeper into a sprawling heap of notes, losing the thread, losing control, which is why we catalogue things in the first place—this goes there, that belongs over there, one step ahead of the chaos. “Right from the start,” writes Benjamin, “the great collector is struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which things of the world are found.”[3] Benjamin, “H [The Collector],” in The Arcades Project, p. 211. “Every passion borders on the chaotic,” Benjamin writes in “Unpacking My Library,” “but the collector’s passion borders on . . . chaos.”[4] Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York, 1969), p. 60.

Of course, this is nothing compared with the maverick organization Aby Warburg made with his amazing library now under threat of dissolution by the University of London. Not for him the Dewey Decimal System! Benjamin wanted to meet, even befriend, Warburg in Germany.[5]See Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life (Cambridge, Mass., 2014), p. 295.

Their theories of the image as movement (like those painted skies), the dialectical image, or Warburg’s infatuation with the nachleben, meaning the afterlife of images, would have forever bonded them, I think. But as usual, luck was not on Benjamin’s side.

As for the contents, Convolute N was itself not short on talismanic power, which is why it was translated by Leigh Hafrey and Richard Sieburth into English in 1983, sixteen years ahead of the rest of The Arcades Project. For those who had no idea of the existence of this cache of carefully catalogued notes consisting largely of quotations, this translation was a jolt from the blue because, along with Convolute K (as Sieburth points out), Convolute N ventured into the heart of his quirky understanding of history, dialectical images, montage, Marxist method, and the prehistoric impulse to the past, to name but some of its key offerings, ruminations, insights, and breathtaking eccentricities. If The Arcades Project is unique for its lavish use of quotations, strung out like a pearl necklace for close to a thousand pages, then Convolute N and Convolute K stand out for their meditation on method, including the concept of the book that was supposed to eventuate.

The question was, How could digging into the past the way he was doing — citing it inexhaustibly — change the present, ushering in a new and better world? a question we all ask ourselves, surely, in our daily lives as much as in our work whatever that work might be. Benjamin’s method certainly had its mystical elements, as does Marxism and as does the Kabbalah,which were present in full force in his method, but at this stage let us merely say the essence of the method was antichronological.

Imagine an artist searching in a box of buttons and pins of different shapes and colors, iridescence and opacities, not thinking too much but wanting to match a pair or several into a constellation that “makes sense.” The different buttons and pins are events that happened in the past. The artist jumps over time to make the match that makes sense, ignoring what happened in between. In Convolute N, Benjamin writes something that shocked me when I first read it: “In order for a part of the past to be touched by the present instant, there must be no continuity between them” (“N,” p. 470). One would be tempted to call this an intuitive method, but what or who is intuitive here, the historian or history? Surely it is history, waiting for its chance.

For this antichronological way of doing history had something chronological about it after all. It was reliant on before-and-after models as well as Benjamin’s idea that changes occur in our ability to experience the world. Experience here means how we perceive and how we process what we perceive, a capacity that underwent seismic changes with modernity, dating roughly from the time when the Paris arcades were built in the early nineteenth century until now.

In other words, the very history that we are setting out to examine influences how we will perceive that history and understand it. This seems very Marxist to me as well as Borgesian. How can we step outside of that which forms us so as to stay ahead of it? Is there any way out of this trap? Might the peculiar form of The Arcades Project provide a way out?

Let us look at Benjamin’s On Some Motifs in Baudelaire for some clues. Here Benjamin sets forth the parameters of this change in the capacity to experience as the distinction between erfahrung and erlebnis, a distinction I will roughly translate as long-haul versus short-haul modes of experiencing.[6]See Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in Illuminations, pp. 155–200. The former relies a great deal on what we could call tradition, habit, and body memory. There is an emphasis here on what I call the bodily unconscious. By contrast erlebnis — child of cities, new technologies, and the accelerated stress patterns of modernity —is all consciousness, so much so that, paradoxically, this genre of experience passes into oblivion, as Sigmund Freud argues in A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’ (1925) and Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920).[7]See Sigmund Freud, “A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’” (1925), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. and ed. James Strachey,(( See Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. Carol Cosman (New York, 2001). vols. (London, 1953–74), 19:227–32 and Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, 18:7–64.)) Erlebnis is a rapid-fire mode of experiencing in which an experience, so long as it is not extreme, burns out as soon as it is born. And it is scattered — perfect reflection of our neoliberal age of tweet consciousness and also perfect for a book that is not a book but a compendium of notes.

The question therefore arises as to whether the form of The Arcades Project corresponds to this erlebnis mentality, yet does so in a way that matches the breathless conclusion to Benjamin’s Baudelaire essay, namely that what Baudelaire’s poetry achieves is giving to erlebnis the character of erfahrung; giving to the scattershot, short-lived mode of experiencing the quality of unconscious bodily force.

Shunting stimuli into oblivion thanks to conscious processing is the work of what Freud called the stimulus shield.[8]See Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, p. 27. If broken through, shock is likely, but finding a Zen position just short of shock might be where an artist like Baudelaire or a work like The Arcades Project wants to be. Are not these thousands of quotations carefully delivered shocks that threaten bodily as much as narrational integrity and whip past our defenses so as to telegraph the unconscious? Benjamin himself once stated that in his work quotations serve like highwaymen so as to rob readers of their convictions.

But above all, consider the library (as in “Unpacking My Library”) itself as a most marvelous stimulus shield where, without our necessarily being aware of it, we go for our erlebnis/erfahrung workouts.[9] See Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library.”

When Benjamin actually speaks outside of his quotations it can seem like he is making a to-do list like a knotted handkerchief. Other times he makes exorbitant demands on himself regarding the philosophy of history, spurring himself on with feel-good images of felling forests with the whetted axe of reason or of a sea voyage exploring the gap between the magnetic pole and the geographic pole and so forth. But these are generally quite muddled if you pause to think about them, yet who would be such a spoil sport?

As for this essay’s epigraph, it too has its share of befuddlement. You lose your bearing in the thickets of its metaphors that almost but don’t quite make sense. A draft, after all. A note in a notebook, after all. Could that be why I like my quotation, the one I put at the very start, for its vulnerability and enthusiasm, its poesy and gravity? A notebook is also a confidante, is it not, something more than a flycatcher? And here I am quoting the quoter!

What of that daydreaming under that “painted summer sky,” especially collective daydreaming? I ask because this question seems to me to be highly relevant to library culture and because Convolute K (which I regard as philosophically partnered with Convolute N) deals not only with dreams but with awakening, specifically with “the flash of awakened consciousness.” Its title reads: “Dream City and Dream House, Dreams of the Future, Anthropological Nihilism, Jung.”[10]Benjamin, “K,” in The Arcades Project, p. 388; hereafter abbreviated “K.” Is not a library a dream house? I ask because I, too, am reading and writing under that painted sky in the Bibliothèque nationale, where Benjamin worked, and I cannot but feel some kinship with the spirit of old Benjamin and through that spirit with the other readers and writers that have sat at these tables under that sky. It is like a sanctuary in here, with its intensity, its silence, and its ethereal beauty.

Is it because of the silence that I feel the energy emitted by the people on either side of me and in front of me? When Benjamin writes of the atmosphere in the library (as in the epigraph to this essay), he evokes that energy as if the paintings of branches of trees against the sky have come alive with their millions of leaves and the fresh breeze of diligence, the breathing of the researcher, and the squalls of youthful zeal scudding along with gusts of curiosity.

Hence my question: Do not these squalls along with this abundance of pneumatic activity gusting through the centuries refer to something primordial such as the collective effervescence of ritual, in this case the ritual of reading in libraries, especially this library? (I leave it to you, the reader, to determine whether the books also participate in this effervescence.)

As for reading, even when alone in the metro, in bed, or on the can, reading is a spiritual communion with the text and also with imagined readers and writers elsewhere. The text is brought to life no less than those readers. But how much more is this the case when on either side of you in a public library, as far as the eye can see, people are buried in their reading? (Did I write “buried”?)

You sense the energy such collective reading emits. It can approach inspired choreography. At times heads bend in unison, gazing into a book or a computer screen. Now and again an older person spurns the digital and writes in pencil in a thick journal. (Could be the spirit of Benjamin except that he loved his fountain pen, not pencils.) People take cell-phone photographs continuously of images in the books they are studying. After all it is now an art-history library. At other times faces disappear in mirage-like waves of compressed concentration in this oasis of learning. Eyes narrow. The body stiffens. You sense the hunter closing in on its prey. Whatever the posture, you feel the energy of the collective. No matter how isolated they may be, lost in their own worlds, each reader seems connected to the others.

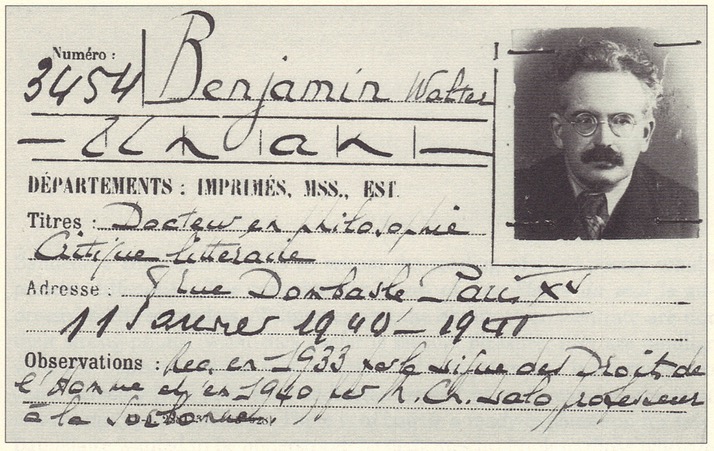

All of which is to say that along with intensity there is this other rhythm, something Benjamin would have been quick to note, namely the power of the daydreaming he must have experienced in the Bibiothèque nationale where he spent most of his time in the 1930s copying down what he called the trash of history, meaning marginalia, the leftovers and discarded materials like what children love to play with in building sites. Years he must have spent there accumulating trash, if you were to add it all up. Years under those mother-of-pearl cupolas and alongside those wall paintings close to the ceiling of green-leafed trees sighing across blue skies. We should also note that for much of this time Benjamin was poor, in bad health, and malnourished.[11]See Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin. By the time he started walking over the Pyrenees from France into Port Bou in Spain in 1940 trying to escape the Gestapo, he had to lie down frequently on account, he said, of his heart. Being Benjamin, he had it strictly scheduled to lie down at set intervals, every half hour or thereabouts. This is what Lisa Fitko, his guide, told me when we talked about that journey at length in her apartment in Hyde Park, Chicago, on Lake Michigan.

Does not the library rhythm of intensely concentrated reading alternating with daydreaming find its parallel in Benjamin’s famous Theses on the Philosophy of History? “Thinking involves not only the flow of thoughts,” he wrote, “but their arrest as well. Where thinking suddenly stops in a configuration pregnant with tensions, it gives that configuration a shock, by which it crystallizes into a monad.”[12]Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, pp. 262–63; here- after abbreviated “T.” This is the sign of a “Messianic cessation of happening, or, put differently, a revolutionary chance in the fight for the oppressed past” (“T,” p. 263).

But which is the daydreaming? Is it the effortless flow of thinking or is it what occurs in the cessation of happening?

This question underlies the epigraph Benjamin appended to Convolute N, a quote from a letter written to Arnold Ruge by the young Karl Marx in 1832: “The reform of consciousness consists solely … in the awakening of the world from its dream about itself ” (quoted in “N,” p. 456).

I see the reader stretched out on the desk asleep under the mother of pearl cupolas refracting the Parisian light, then startled into wakefulness, saying to him or herself, “I’m not asleep. I was awake all the time. Thinking. Thinking dialectical images, one after the other. Setting the sails — fighting for the oppressed past.”[13]On setting the sails in relation to the dialectical image, see “N,” p. 473.

Something like that.

The quote from the letter to Ruge was certainly from another Marx, a Marx before Capital. But then Benjamin was his own type of Marxist, (indeed, did he even need Marx?) and this emphasis on awakening resonated not only with Convolute K but with his focus on Marcel Proust’s extraordinary achievement in directing our attention to sleep, to falling asleep, and to waking (something Roland Barthes places at the center of his last lectures, published as The Neutral [2002]).[14]Roland Barthes, The Neutral, trans. Rosalind E. Krauss and Dennis Hollier, ed. Thomas Clerc and Eric Marty (New York, 2005).

As for awakening, this is akin to Proust’s memoire involontaire, which happens when, thanks to a sensation, an unexpected connection is made resulting in an ever-expanding image of the past in the present. More like a documentary movie than a static image, this awakened visual memory image infiltrates one’s body brought to a state of such excitation that, in Proust it can seem orgasmic. And not only does it infiltrate the body of the person remembering. It spreads further into the body of the world. It becomes ever wider in focus to become an expanding moving image as described in the first account of its happening early on in Swann’s Way where the narrator recalls the village of Combray unfolding in successive waves through the bedroom window of his aunt Léonie. Like Japanese paper flowers and other figures unfolding when in water, he says.[15] See Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way, vol. 1 of In Search of Lost Time, trans. Lydia Davis, ed. Christopher Prendergast (New York, 2004).

The importance of awakening in Benjamin’s thinking about revolution is rarely pointed out in Benjamin studies. Yet there it is plain as can be as the epigraph to Convolute N. The opening passages in Convolute K, centered on awakening, are virtually ignored by most commentators even though they are, in my reckoning, the backbone of the project. “What follows here,” writes Benjamin in the first paragraph of Convolute K, referring to the Arcades Project as a whole, “is an experiment in the technique of awakening.” Further down the page he will refer to “the flash of awakened consciousness” and he will set forth two ideas of considerable importance pertaining to this (“K,” p. 388).

The first is that between sleep and awakening there are many states of consciousness, in fact “an unending variety of concrete states of consciousness,” and the second concerns the parallel between the individual and society. “The situation of consciousness as patterned and checkered by sleep and waking need only to be transferred from the individual to the collective” (“K,” p. 389).

“Need only to be transferred.” Only! Well, there’s a thought!

As for the many states of consciousness between sleep and waking, is not this spectrum in plain view in the reading room under the dreamy unlit ceiling? Does not this oscillation between sleep and waking achieve one of its most fervid forms in public libraries? Anthropology attests in detail to similar states of fluctuant consciousness in states of spirit possession such as Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Native North America, Latin America, and the US Northeast in the nineteenth century. That is a long list, so long that it is exceedingly strange that with a few important exceptions, spirit possession does not occur in the Euro-American heartlands, yet here in the very heart of the heart — in the pinnacle of civilization as represented by the treasure trove of books housed in the exquisite taste and architecture of the Bibilothèque nationale, a stone’s throw from the Louvre — we find states of consciousness the same as or parallel to those of spirit possession en masse in the postcolony. (In this regard I often wondered, à la Breton, the pope of Surrealism, about the weakly illuminated Chinese-run café next door to the library, which sold lottery tickets most days at a rate and volume to rival a casino. It was just the sort of place Nadja and Breton would have frequented.)

A few paragraphs further along in Convolute K we read the astonishing claim that there exists a microcosm/macrocosmic identity between the insides of the human body and its sociocultural surround — including the weather, fashion, and architecture: “And so long as they preserve this unconscious, amorphous dream configuration, they are as much natural processes as digestion, breathing, and the like. They stand in the cycle of the eternally selfsame, until the collective seizes upon them in politics and history emerges” (“K,” pp. 389–90). This micro/macrocosmic identification waxes and wanes along with the movement from sleeping to waking. It is an idea reminiscent of the final two pages of Benjamin’s 1929 essay on surrealism where he evokes the image-body sphere and the awakening of a collective consciousness by the collective body.[16]Benjamin, Surrealism, in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott, ed. Peter Demetz (New York, 1986), pp. 177–92. Could the reading room of the Bibliothèque nationale provide a model — nay, the model — of this macro/micro process? Here the beauty of the library gives shape and form to the love stories (horrific stories, I was about to say) concerning Benjamin’s immersion in books. If his essay “Unpacking My Library” can be read as a meditation on collecting focused on his own, private, collection of books, stolen from him in Berlin with the ascension of the Nazis, how much more of a treasure is the cornucopia of books that is the Bibliothèque nationale?[17]See Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library.”

This mix of love and horror stimulated by the books in one’s library and in public libraries was unforgettably awakened for me by the British historian E. P. Thompson in his address at the opening of the Eugene Lang undergraduate school of the New School for Social Research in New York City in the 1980s. While the other speakers such as Perry Anderson, Eric Hobsbawm, and Christopher Hill spoke to issues such as what is meant by cause and effect in history (without a trace of Benjamin!), Thompson grabbed everyone’s attention with his opening statement (as I recall) to the effect that “I have given up studying history so that there will be history for others to study.” He was referring implicitly to his work on nuclear disarmament and went on to say (as I recall): “When I walked here this morn- ing and passed the New York Public Library on 42nd Street, my heart soared at the thought of the treasure therein.”[18]E. P. Thompson, lecture at the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, New York, 20 Oct.1985.

As for Benjamin, the term bookworm seems far too mild for him. He lived in books, he cannibalized books, he virtually made love to books and vice versa; they were his great friends through thick and thin — much to the despair of his long-suffering wife Dora and others. He seems to have lived not only in the world of reading but in the world of books, qua books, more than in the human world. No wonder that he was always thinking of putting together and publishing books with nothing but quotations. No wonder that his most elegant and easy-to-read essay, the one that Hannah Arendt chose to open Illuminations, is called “Unpacking my Library.” Even more to the point, the library he is referring to turns out to have some peculiar properties. It can function as a “magic encyclopedia,” one that can be consulted for divination.[19]Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” p. 60. Perhaps the oddest and certainly most charming thing is the way the reader at the end of the essay disappears into the books even more than the books disappear into the reader, all of which is to say that books and libraries are more than meets the eye.

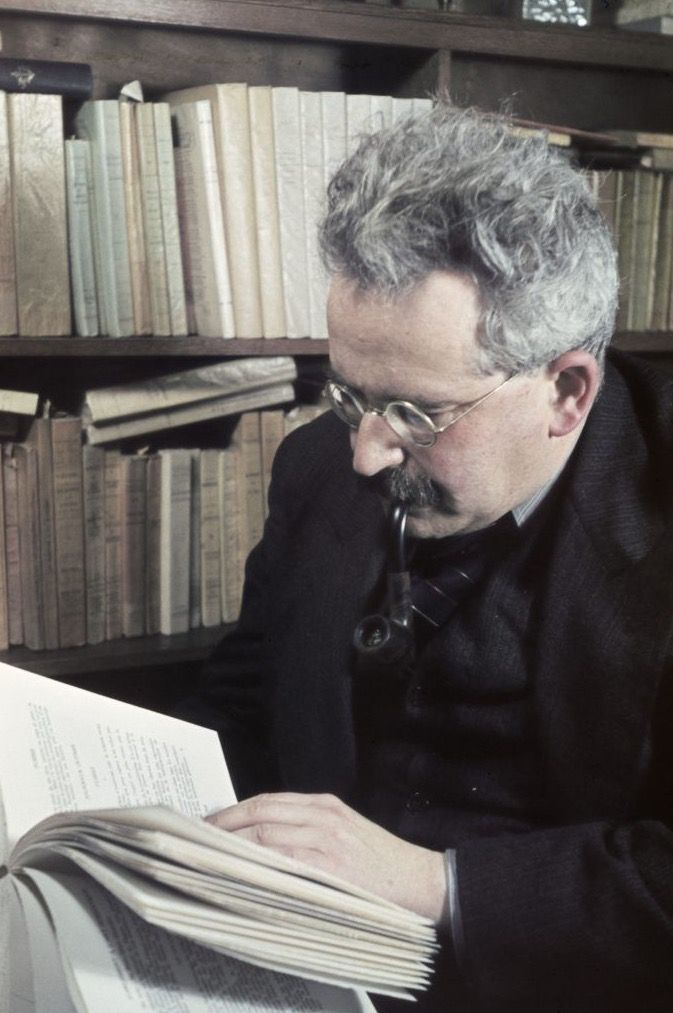

You can see a few photographs by Giselle Freund of Benjamin sitting at a desk in the library looking suitably scholarly, which was not hard for him. But she seems to have ignored the mother-of-pearl cupolas and the trees in the sky and focused instead on his face and his posture seated in his chair. Perhaps that was because—so I was told by the librarian—he actually worked downstairs. What’s more, the librarian said, you can’t go there today. It’s full of machinery. So, once again, the loser is pushed out of sight of the sky, the sky-high trees, and those aura-evoking mother-of- pearl cupolas.

Could this be why he inserted that out-of-character paragraph in Convolute N, the one about the painted sky? All he could do was dream of it, like a Warburg afterimage.

Yet as for the method extolled in Convolute N—this method of loosely connected fragments, most of which were to be quotations—how much of this was actually intended as the final product? It is certainly plausible to assume that if a book had emerged, it would be largely quotations (as with the earlier book on Trauerspiel ), yet what we have today is surely not what Benjamin intended but a set of notes in a notebook, a huge notebook, but still a notebook. It is this notebook character that makes reading it both charming and tedious.

At the risk of pedantry let me say there are two issues here. One concerns the theory of literary montage by which I mean fragmentation designed to weave images together through the combination of dissimilars, thereby evoking imaginary worlds (and a view of history as a mosaic).

The other and more original issue here concerns the power of note-books, which are by no means consciously designed as literary or filmic montage but can be read that way (as I have suggested elsewhere in relation to ethnographic notebooks).[20]See Michael Taussig, I Swear I Saw This: Drawing in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own (Chicago, 2011).

But here, in the library, I want to ask: What is reading, anyway? The author may be a producer but then so is the reader; The Arcades Project asks its reader to weave and shuffle the fragments like cards in a pack (as Bertolt Brecht said in reference to Alfred Döblin).

We need to be careful here of falling into a false dilemma. Either we see The Arcades Project as incomplete or we mindlessly celebrate its fragmentation. But what if we tilt our attention away from the writer towards the reader, who is likely to be immersed in what Benjamin called the “time of the now” (“T,” p. 273) of “dialectics at a standstill” (“N,” p. 463)? Is this not where the quotation qua quotation lives and breathes, poised, waiting, for a response?

And what of that other quotation—those painted summer skies hanging over the readers’ bent heads? Are they not also bursting with the tension and energy of “dialectics at a standstill”?

Just as history as experienced, according to an entry in Convolute N, gives way to stories, and stories give way to images, we cannot easily ignore the movement in those painted skies and what, together with the translucence of the mother-of-pearl cupolas, such movement implies for history understood as stilled images on the move, a motility brought to our atten- tion by Philippe-Alain Michaud in his recent book on Warburg (see “N,” p. 476).[21]See Philippe-Alain Michaud, Aby Warburg and The Image in Motion, trans. Sophie Hawkes (New York, 2007).

Speaking of movement in stillness, the pages of The Arcades Project are chockablock with chips of pastness throwing us this way and that. You can feel Benjamin carving out a space in the nineteenth century, a space like the arcades themselves, into which we readers are being invited to come and wander. It is a space alive with the spirits of the dead inhabiting the world of European revolutionary traditions (Louis Auguste Blanqui was a favorite with his astral sense of time and space, along with Charles Fourier and his seas of lemonade). Overall this was an attitude towards history and memory in which the present instigated its “rescue” by forming an eccentric and passionate fusion with elements in the past, flashing forth at a moment of danger such as Europe was experiencing in the 1930s and is now experiencing again.

And today, what of daydreaming on the verge of sleep on the part of the readers reading in the reading room? Are they not, as the surrealists might claim, daydreaming in a dream space of capital as housed by the arcades way back in the early nineteenth century? For is not the Bibliothèque nationale on the rue de Richelieu with its dreamy ceilings an arcade itself ? Is it not the mother of all arcades, posing as a library with its slender cast- iron columns, extending the extraordinary sense of lightness of the cast- iron technology that came in for focused attention in The Arcades Project?

Benjamin makes this equation between the library and the arcades when he writes early on in Convolute N of “the painted summer sky that peers down from arcades in the reading room.” Designed by Henri Labrouste in 1867, the reading room ascends from the readers’ desks in their orderly rows to the book-lined walls up, up, into the luminous domes of the ceiling, transmitting the light of the sky onto the paintings of the skies screened by green boughs that mediate, so to speak, the ethereal world of those mother-of-pearl domes with the scholars below. It surely qualifies for what Benjamin in his essay on surrealism called a “profane illumination.”[22]Benjamin, “Surrealism,” p. 179. This particular arcade poses as a library providing cultural treasures of the past to avid con- sumers of those treasures, a library across whose portal could be inscribed those often quoted words in Benjamin’s last writing that “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism” (“T,” p. 256).

Yet libraries like the one I am describing seem increasingly like an ideal type or Platonic idea. This is because libraries today have shrunk as places meant for the collective reading of books. In my university they are basically places for students doing homework while listening to music and furiously texting each other. And I doubt that professors today go much to libraries and form part of the reading collective that I have described above. They have assistants who go to get books for them or else the books are delivered to their office by library staff. Indeed, in my own university such virtuality is encouraged, and I get the feeling that the more important a professor, the less likely are they to sit down at a table in the library full of students. Perhaps, as with flying, there will soon be first class and economy?

What a contrast with the libraries in which I worked as a student. Not only would I see professors rummaging excitedly through immense card catalogs, but the library was where you met everybody and where, given that there were no copying facilities, people would scribble comments in the margins of journals, and other students would write comments on the comments, ad infinitum.

And how many brilliant theses, I wonder, were born from the odd, dreamy glance or even the meditation of oneself in the eyes of other readers with whom one detected an elective affinity or the physiognomic route to an idea?

I have heard it said that the stacks of libraries where books are housed are places for trysts, and I have no doubt this is true, not merely because of the privacy they provide, but because of the erotic quality of the library — by which I mean that social energy I referred to earlier where spiritual communion is established merely by reading. The tryst, then, would be the carnal fulfillment of that. Speaking for myself, I still recall the grace, generosity, and good humor of the librarians I got to know at the London School of Economics and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor long before the internet came and ruined everything. As for the readers, even disembodied scholars with ice water running through their veins can be turned on by books.

So what can be said about the library today? “To Restore Civil Society, Start With the Library,” a recent op-ed in the New York Times by a professor of sociology, provides a list of valuable social functions libraries can serve such as companionship, de facto child care, welcoming public spaces for the poor and homeless, as well as help with personal problems.[23]See Eric Klinenberg, “To Restore Civil Society, Start with the Library,” New York Times, 9 Sept. 2018, These are valuable functions, but let it not be overlooked that they spring from the magic of books and reading on a collective scale.

Full of books, the organic energy in libraries, apart from trysts in the stacks, is not always easily deciphered. The energy is blanketed by silence, somnolence, and gravity. Like the rest of us in academe, libraries perform scholarship, yet above our bowed heads the mother-of-pearl cupolas glow with a different story.

Sometimes the social energy emitted by collective reading can be so overwhelming that protection is sought, not in the stacks, but with blankets. In the case of the Bibliothèque nationale in the rue de Richelieu where Benjamin sat for a decade, the blankets are scarlet.

Yes! It is an astonishing sight to see someone returning to their seat with a scarlet blanket around their shoulders like a shawl or Latin American serape. Huddled over and bulked out like that, they are transformed. They have become Tibetan monks, as if now they truly personify the spiritual energy of collective reading alive with the glow of the cupolas and those trees painted against cloudy skies. It starts slowly. One person leaves and returns wrapped in scarlet. Then another person rises from their seat and returns and, as in a collective hysteria, others follow suit. After an hour or so almost my entire table-load of fellow readers has become a Tibetan monastery, and the character of this extraordinary building has changed. For sure, the blanketed figures are beautiful. But more beautiful still is how this ritual in its sweeping power occurs wordlessly and spontaneously as if nothing is happening, nothing at all except that reality has been turned inside out. The library has become mythical. We are now actors in an unwritten drama.

It is August, the height of summer, 2018. The librarian tells me that since the French are not used to air conditioning, blankets are provided because they feel cold in this air-conditioned building. “Has anyone correlated what a person is reading with their body temperature?” I asked her in jest (yet I am attached to this idea). I don’t think people feel cold. What happens in my opinion, having spent a fair bit of time in libraries, is that the air-conditioning cools the air heated by the collective effervescence (see Émile Durkheim on the collective effervescence of “primitive” ritual), such that the readers feel anxious and disturbed, cheated of their collective creation, the collective heat of reading. They resort therefore to artificial means such as flaming red blankets that the library supplies in abundance. They are now flames themselves, some simmering, others rising like angels to where, in 1940, as Benjamin fled Paris, Georges Bataille hid the notes that today we call The Arcades Project.

First published in Critical Inquiry 46 (Winter 2020) . Re-published by herri with kind permission of the Author and the Publisher. Copyright 2020 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

| 1. | ↑ | Walter Benjamin, “N [Re The Theory of Knowledge, Theory of Progress]” in Benjamin: Philosophy, Aesthetics, History, trans. Richard Sieburth, ed. Gary Smith (Chicago, 1983), p. 44. |

| 2. | ↑ | See Benjamin, “N,” in The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge, Mass., 1999), pp. 456–88; hereafter abbreviated “N.” |

| 3. | ↑ | Benjamin, “H [The Collector],” in The Arcades Project, p. 211. |

| 4. | ↑ | Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York, 1969), p. 60. |

| 5. | ↑ | See Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life (Cambridge, Mass., 2014), p. 295. |

| 6. | ↑ | See Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,” in Illuminations, pp. 155–200. |

| 7. | ↑ | See Sigmund Freud, “A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’” (1925), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. and ed. James Strachey,(( See Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, trans. Carol Cosman (New York, 2001). |

| 8. | ↑ | See Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, p. 27. |

| 9. | ↑ | See Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library.” |

| 10. | ↑ | Benjamin, “K,” in The Arcades Project, p. 388; hereafter abbreviated “K.” |

| 11. | ↑ | See Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin. |

| 12. | ↑ | Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, pp. 262–63; here- after abbreviated “T.” |

| 13. | ↑ | On setting the sails in relation to the dialectical image, see “N,” p. 473. |

| 14. | ↑ | Roland Barthes, The Neutral, trans. Rosalind E. Krauss and Dennis Hollier, ed. Thomas Clerc and Eric Marty (New York, 2005). |

| 15. | ↑ | See Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way, vol. 1 of In Search of Lost Time, trans. Lydia Davis, ed. Christopher Prendergast (New York, 2004). |

| 16. | ↑ | Benjamin, Surrealism, in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott, ed. Peter Demetz (New York, 1986), pp. 177–92. |

| 17. | ↑ | See Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library.” |

| 18. | ↑ | E. P. Thompson, lecture at the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, New York, 20 Oct.1985. |

| 19. | ↑ | Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” p. 60. |

| 20. | ↑ | See Michael Taussig, I Swear I Saw This: Drawing in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own (Chicago, 2011). |

| 21. | ↑ | See Philippe-Alain Michaud, Aby Warburg and The Image in Motion, trans. Sophie Hawkes (New York, 2007). |

| 22. | ↑ | Benjamin, “Surrealism,” p. 179. |

| 23. | ↑ | See Eric Klinenberg, “To Restore Civil Society, Start with the Library,” New York Times, 9 Sept. 2018, |