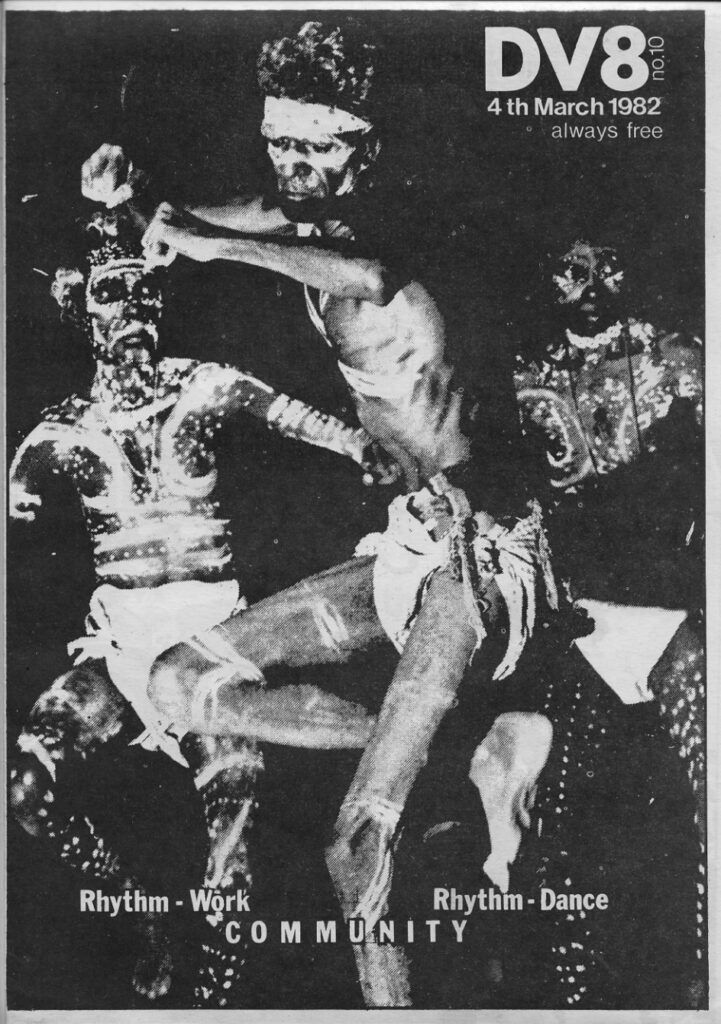

We used to call it a ‘magazine’, DV8 magazine to be precise, named after the nightclub. DV8 was in the basement of a hotel in Twist Street, Johannesburg, directly opposite Joubert Park, a stone’s throw from the South African Defence Force’s Witwatersrand Command Headquarters, and a brisk walk from Hillbrow.

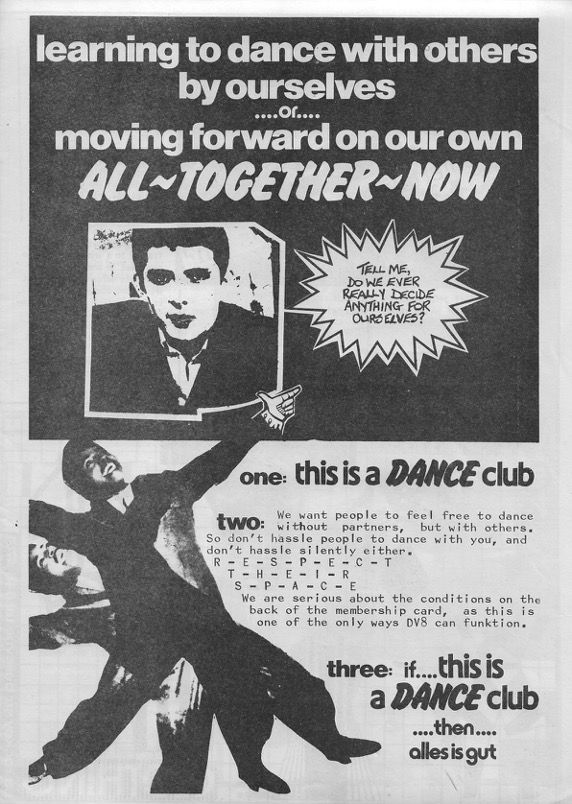

DV8 opened in January 1982. It was the most recent reincarnation of a series of nightclubs established by Martin Vogelman, one of the most progressive deejays of the era and a not always very profit-oriented entrepreneur. DV8 was a peculiar mix of private business and community – regulars were not only regular, DV8 was ‘home’ to many who were seemingly ever present on club nights, usually Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays.

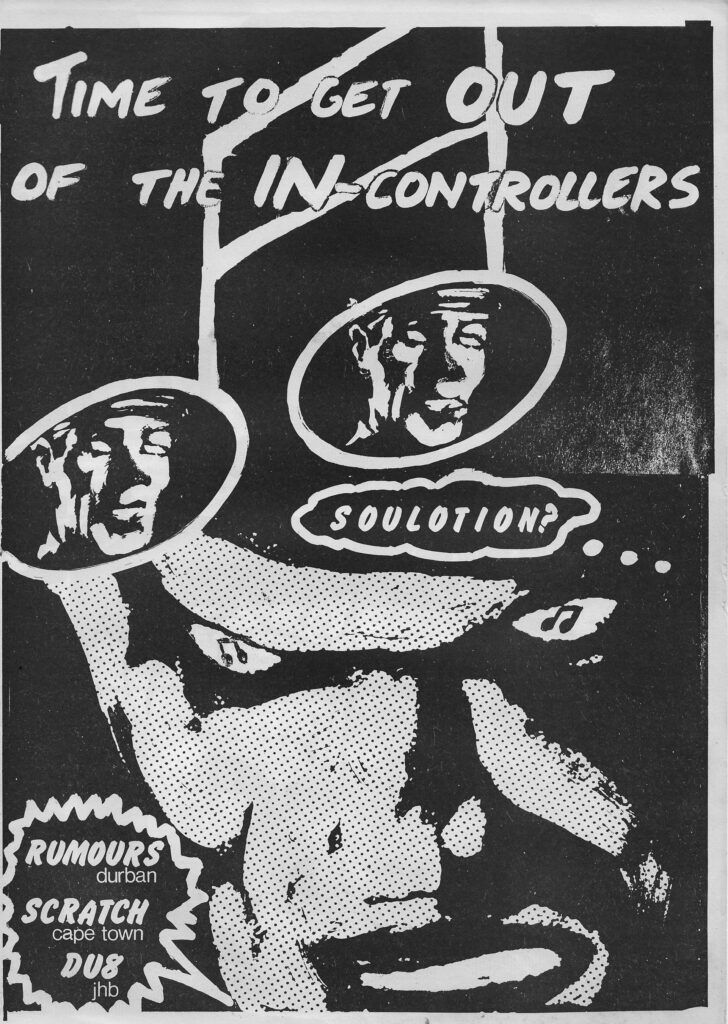

I was there from its inception – my first job after art school, employed as resident deejay, arriving in the final days of Metal Beat, the predecessor to DV8. I barely knew Martin, but secured the job on the basis of my involvement with Scratch, a fraternal nightclub in Cape Town. These clubs, along with other less sustained ventures in Durban, were like an extended family. If you were new in town, or just passing through, you could easily assimilate into your new environment thanks to these spaces providing a locus for belonging.

That said, the nature of this belonging was constrained by the segregationist policies of the day. Scratch got around this by disallowing alcohol. It was also aided by its proximity to the central train station. These factors enabled Scratch’s evolution into a club with a largely black clientele, leading to intense police harrassment and finally forced closure.

In contrast, DV8’s location in a whites-only hotel (where the bar was an integral part of the business arrangement) compromised prospects for black clientele, if they could make it across town without being stopped by police. This led to DV8 being a largely white club, although the dancefloor pulsed as much with the sounds of Fela Kuti, James Brown, Grace Jones and Black Uhuru as it did with Talking Heads, Kraftwerk, Cabaret Voltaire and Simple Minds.

One thing that distinguished DV8 from its immediate predecessors was that it benefitted from the migration of some of the core Scratch crew, namely Lee Hobbs, Hazel Crampton, and myself. There were several other regulars with a related lineage, but it was Lee and Hazel whom Martin gave the task of producing the club magazine. Over the next year the publication went from its original folded A4 sheet to, at its peak, a 48 page A4 sized monthly publication. Without a doubt, the quality and character of the magazine distinguished DV8 from its contemporaries.

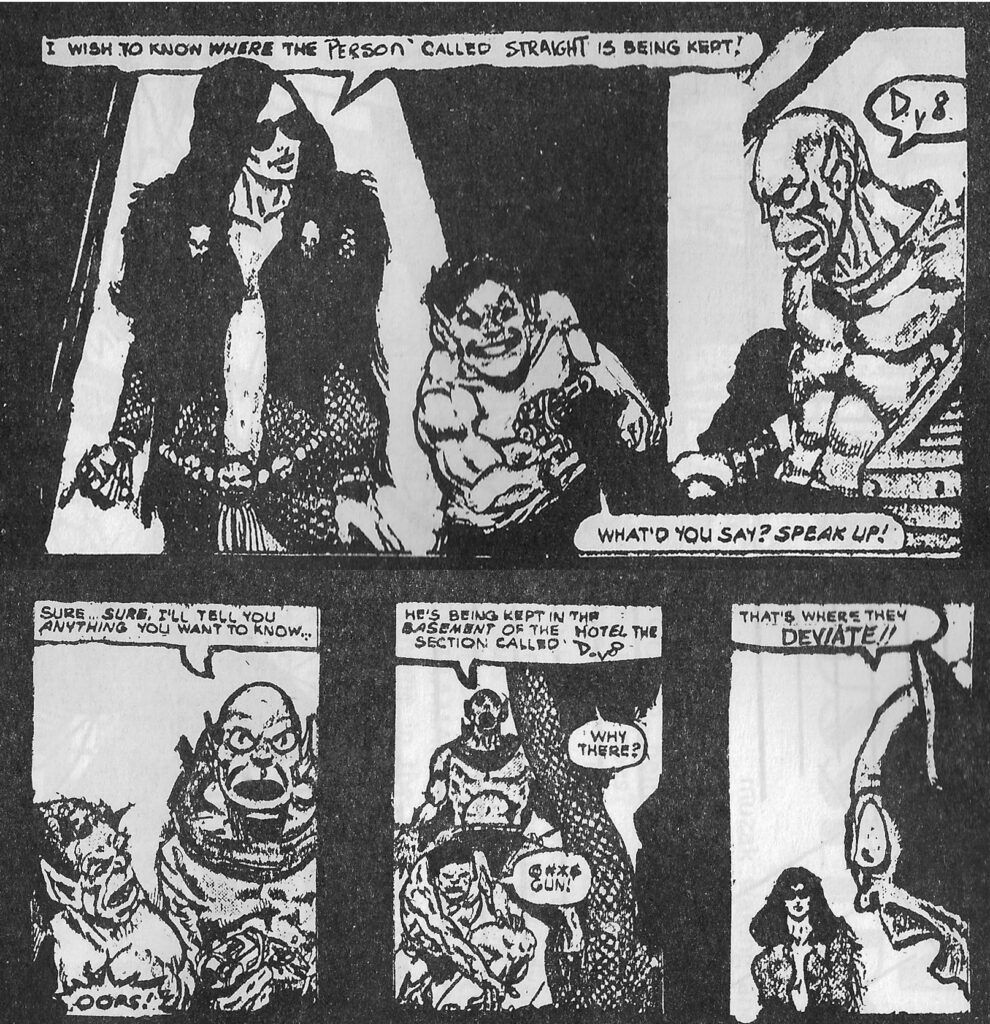

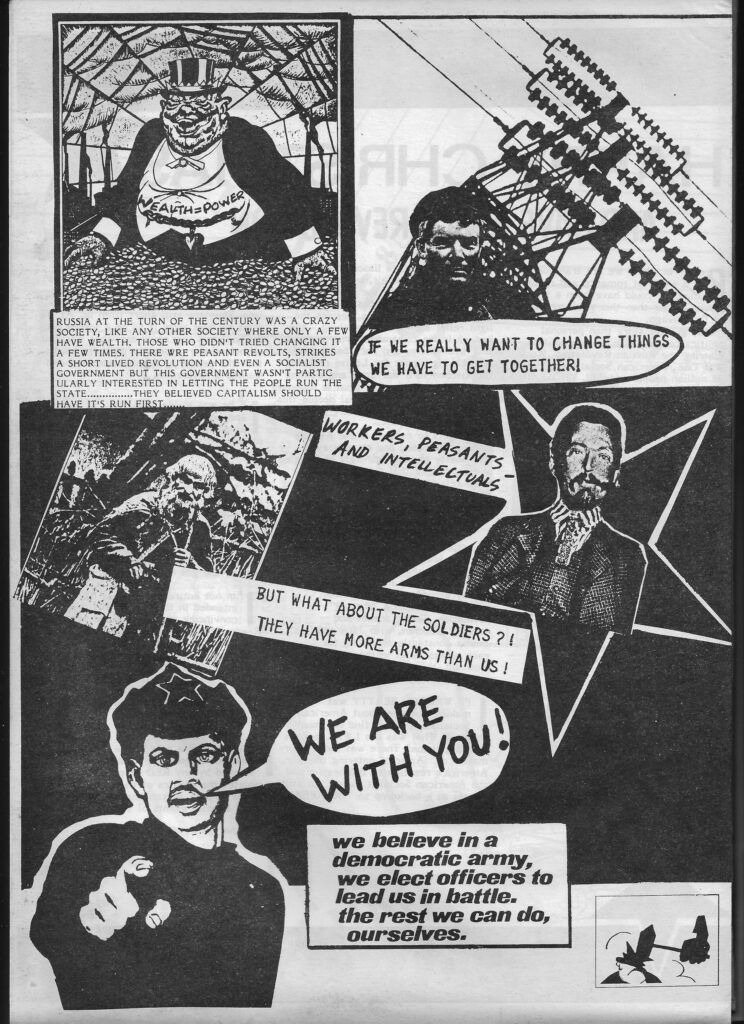

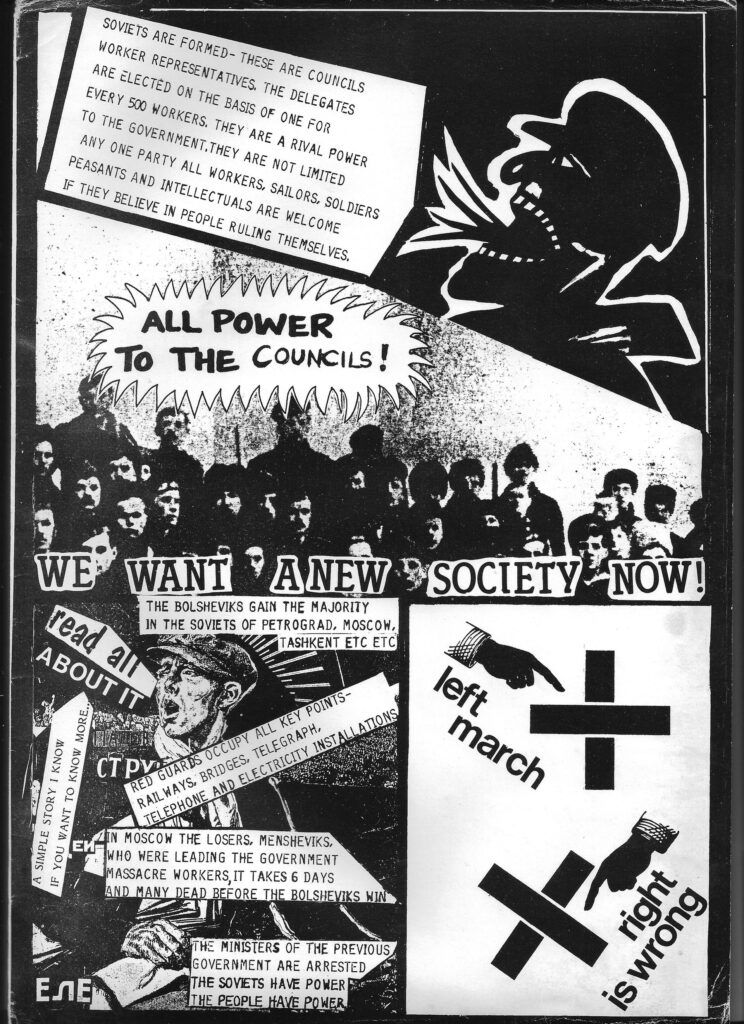

DV8 magazine was a strictly non-commercial affair, given out freely to club goers. Most of the content was original and, unsurprisingly, much of it was music related – there were features on Via Afrika, Shifty Records, Juluka, Malcom McLaren’s colonial foray into mbaqanga, Hip Hop, and Rastafari in South Africa, along with a column on locally distributed reggae imports, playlists, and reviews of the music being played at the club. There were also fairly regular film and book reviews – a review of Julie Frederikse’s None But Ourselves got three full pages. This material segued into more recognisably political content – features on the cultural boycott, nuclear power, the Russian revolution, the CIA coup in Chile, and Palestine all come to mind. There were also several original comic strips. Contributors were rarely identified, with most items credited to an ever changing roster of pseudonyms, usually irreverent in their invention.

There can be little doubt that DV8 magazine fulfilled a role for creatives to publish outside of the limited constraints available at the time. My first critical text – where I argued that Factory Records had cynically exploited the tragic death of Joy Division’s Ian Curtis – was for the magazine. Among the contributors one finds future authors (Hazel, Michelle Rowe, Roger Smith, Donald McRae), experimental film makers (Anthony Chase and Oliver Schmitz), and future sound engineers and music archivists (Ian Osrin and Steve Gordon). Of these Michelle, Anthony and Ian can be counted among the regular contributors, as can Lee, who wrote some of the more politically acute critiques, and of course Martin, whose playlists provide archival evidence of the experimental and eclectic space occupied by Dv8.

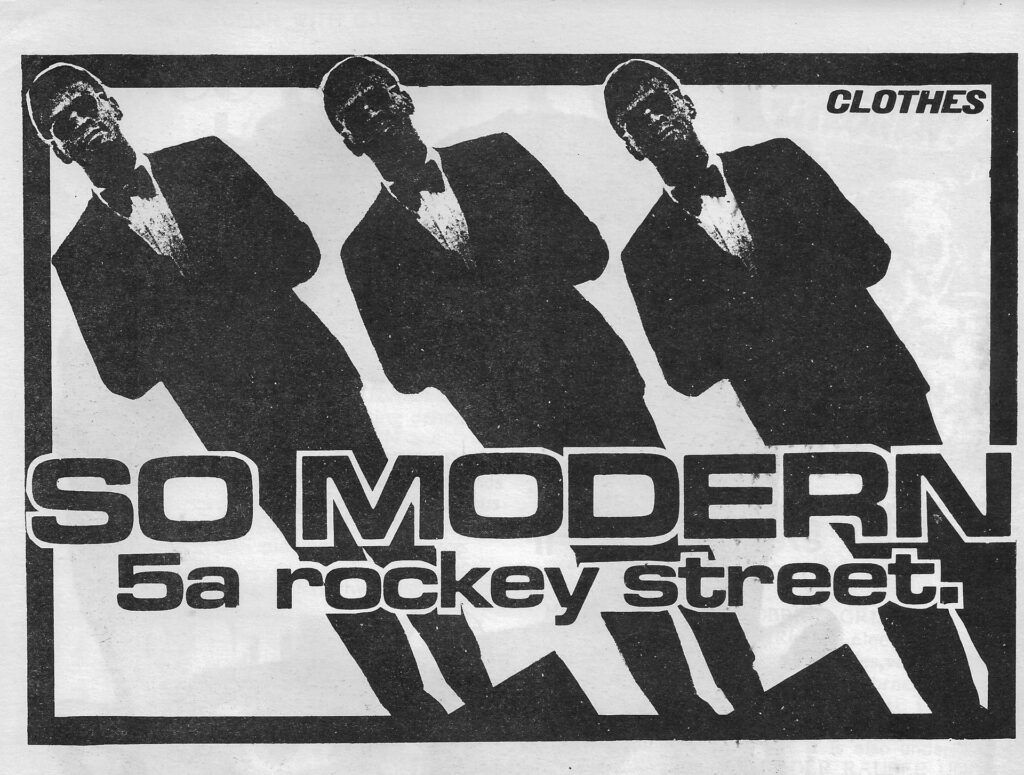

Adverts, mostly unpaid for and generally not a prominent feature, add to the archival value of the magazine, providing rare references to largely unwritten histories of local youth culture.

Regular inserts for Vinyl Jahnkys remind us of the once buzzing record store, almost on the doorstep of the Carlton Centre (then a jewel of white urban culture). Vinyl Jahnkys (owned by Ian) was in part a distribution point for much of the contemporary reggae and post punk music coming from the UK – labels distributed included Mikey Dread’s Dread at the Controls, Negus Roots, Greensleeves, On U sound, and a host of independents linked to Rough Trade. All this during the cultural boycott. On Saturdays Vinyl Jahnkys, with Ras Farouk at the controls, was a skanking and smoking satellite for the city’s rastas.

So Modern, one of two ‘alternative’ clothes stores on Rockey Street, where many club regulars purchased designer ware at not unreasonable prices, is another regular feature among the adverts. There are also notices that recall forgotten record outlets, like Urban Sound in Durban, as well as obscure notices for independently produced cassettes.

All that I have said here does not explain the real success of DV8 magazine. Many zines were similarly eclectic, travessing a terrain that was in parts a reflection of the social alienation of youth, along with an earnest call for change. Where the magazine rises above its cultural peers is in its aesthetic quality, which frequently disrupts distinctions between text and image.

This is a pattern that became more pronounced with each addition. Here the success can be largely attributed to Hazel, who had a background in fine arts. With few exceptions (such as the music pages I produced, using basic cut and paste, tippex and letraset), she designed the pages and produced most of the covers, often playing with the ambiguous idea of the magazine as ‘free’.

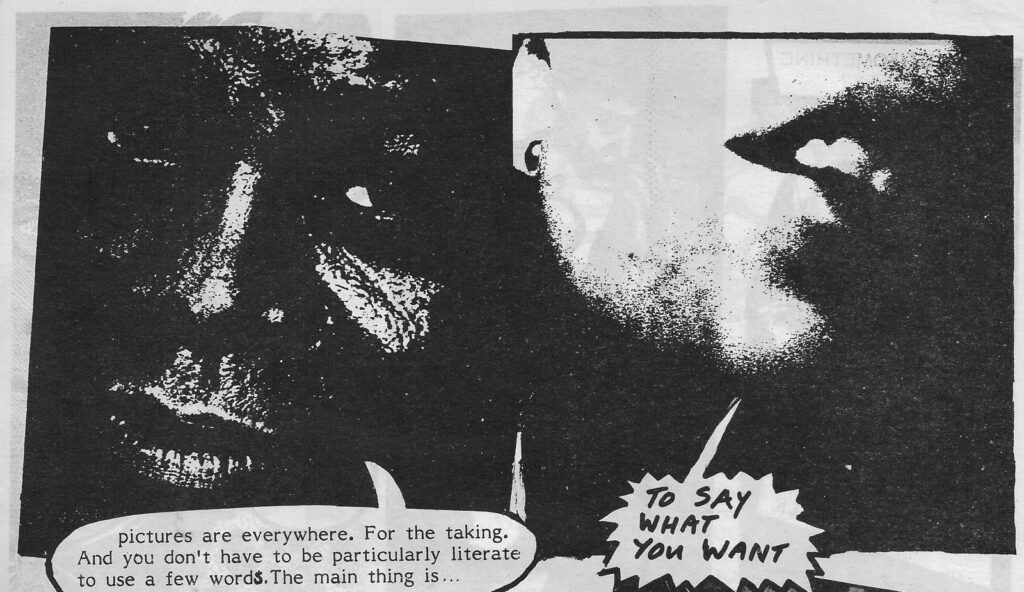

Where Hazel really elevated the magazine was in producing a startling series of non-linear graphic sequences. These adapted the idea of the comic book, with speech bubbles and captions acting to reframe the mostly found images she sourced from children’s books, magazines, comics and who knows where. These typically ran over several pages. She also produced several stand alone quasi-poster graphics, often for the back cover.

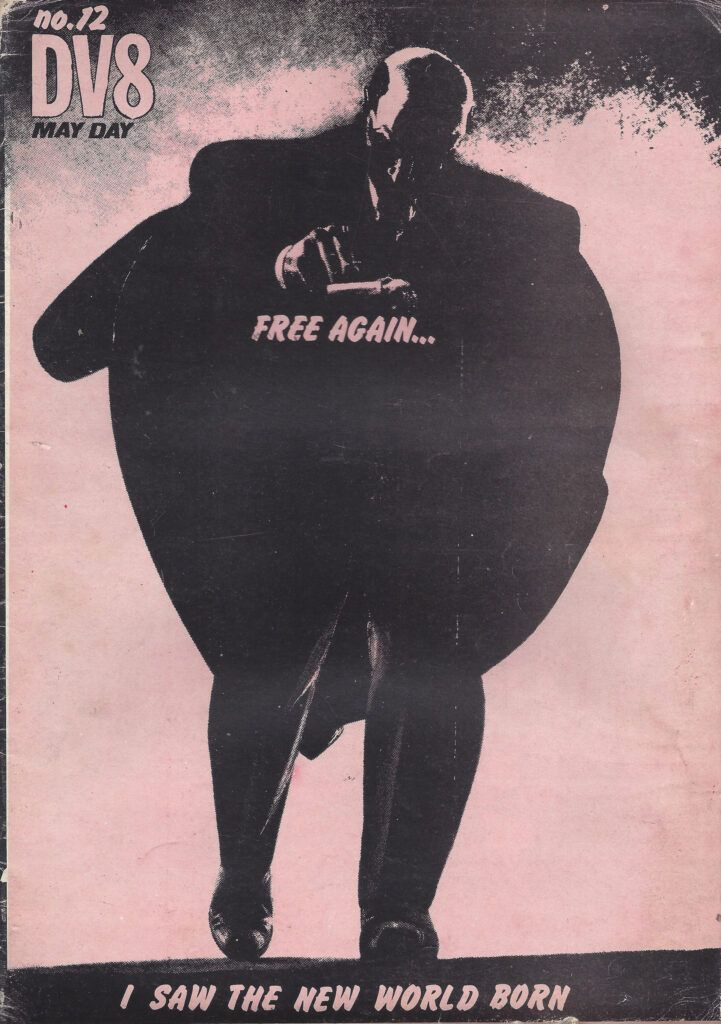

Through her graphics the feminist, anti-colonialist, anti-militarist and anti-capitalist perspectives that erratically punctuated the magazine surfaced with dramatic flair. But mostly the content of her work skimmed the perimeters of agit-prop, filtered with an absurdist edge that must have perplexed the authorities. A cover image of Lenin looking like Dracula rolling a joint, set against a pink background with the legend ‘free again… I saw the new world born’ is exemplary of the multi-layered cultural and political references that found expression in her work for the magazine.

It was largely due to Hazel that the publication went beyond the punk DIY fanzine, begging a retrospective dialogue on its historical place within contemporary cultural and political movements.

I left South Africa at the end of April 1983, my savings from my tenure as club deejay rescuing me from military conscription. By then the magazine had ceased publication. Martin had never been one for tightening reins, and with the magazine bulging further with almost every edition, I suspect it had to do with the rising costs of printing, coupled with the commercial challenges of sustaining the club.

In hindsight I imagine that its demise would have been fortuitous for Hazel and Lee who were recruited into the political underground in 1983. I don’t think their commander would have approved them putting out pro-Soviet features when they were doing risky work that required them to be off the radar. This information was not known by their peers – for instance, I only learned of Lee’s activities when she recruited me in 1989.

Does the knowledge of subsequent political activity by core contributors to the magazine alter the way we read it today? Does this information enable us to link some of the critical and provocative content to graphic works from other contemporary South/ern African movements that were more explicitly anchored in the ‘political’, such as the Medu Art Ensemble, or the poster workshops that were set up in Cape Town and Johannesburg after the Culture and Resistance conference in Botswana, or the End Conscription Campaign that came a little later?

Is it far-fetched to bring a publication that targeted a largely white, urban, clubbing audience into a reappraisal of the cultural work of the 1980s? Does it fit squarely into conceptions of dissident white culture, or should it be inserted into a longer trajectory of literary and cultural magazines that include the likes of Staffrider and Chimurenga?

Alternately, should its legacy be appraised internationally, within the contexts of post-punk, post-modernism and, particularly with Hazel’s graphics, international feminist art?

Then again, being self-professed as deviant, why should it fit anywhere at all?