HILDE ROOS

Sicula iOpera – a raised fist?

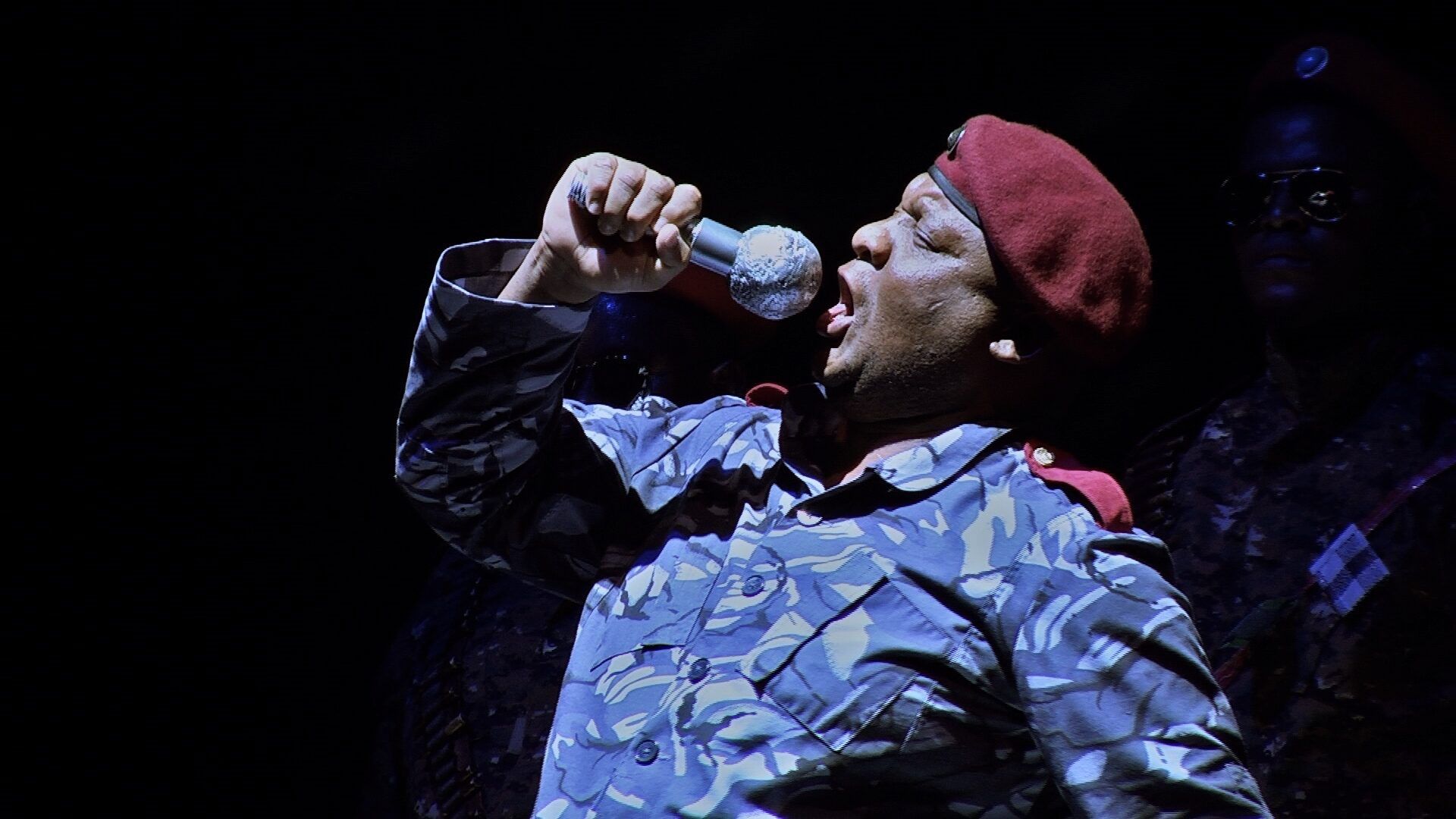

The image of a large red fist-shaped fez on Owen Metsileng’s head remains an enduring visual memory of Catherine Henegan’s documentary film Sicula iOpera. With the spotlight on Macbeth in the darkened theatre, the red and brown colours of the image augment Metsileng’s sonorous baritone, voicing a mixture of power and angst. A small orchestra, playing yet another re-imagination of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Macbeth, accompanies Metsileng. The red clenched fist feels like the right image to start writing about this film, a way into the maze of associations, impressions and archaeology suggested by the film.

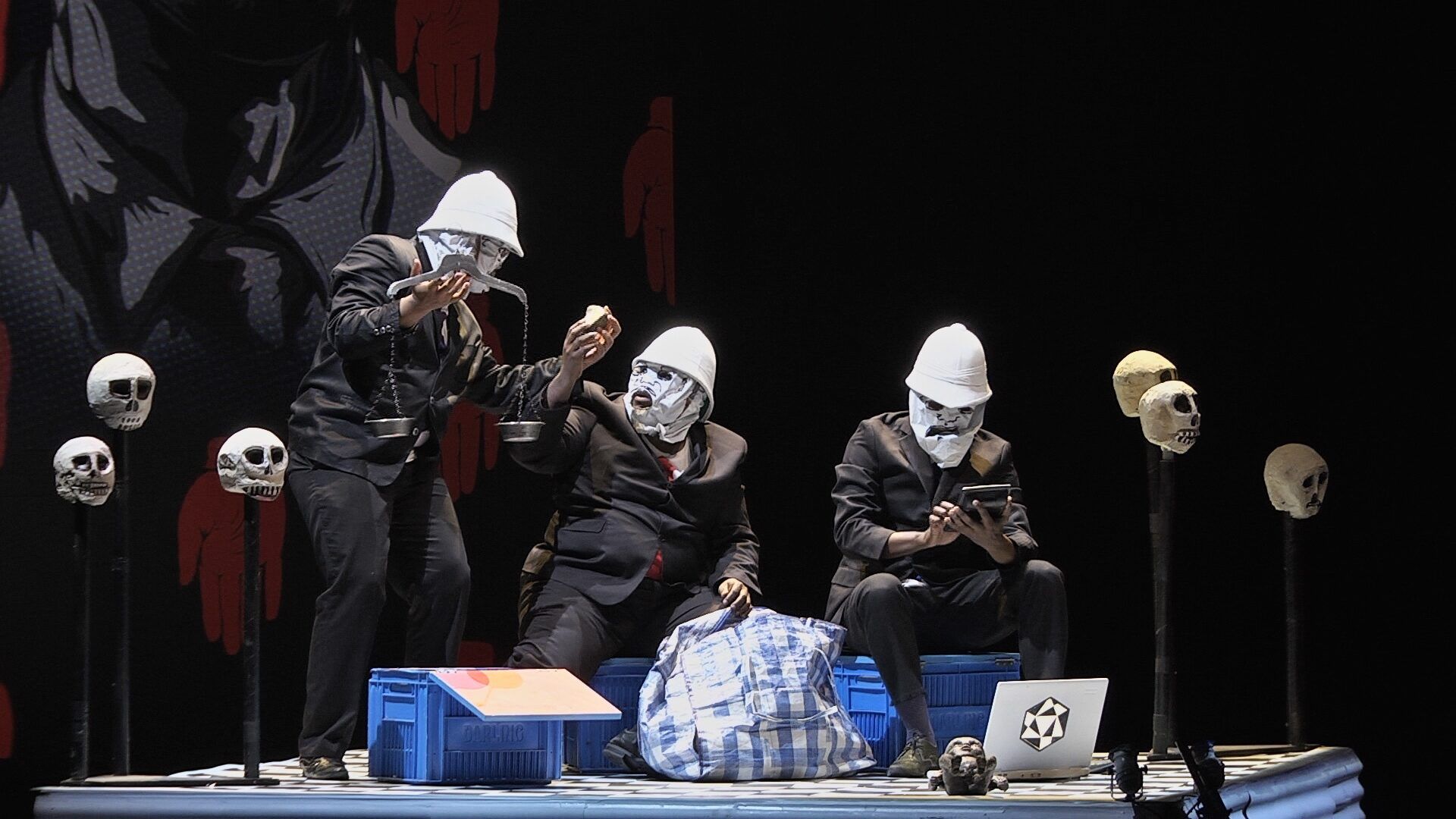

The fist-shaped fez was theatre director Brett Bailey’s choice to visualize Macbeth’s power, the king who murdered his former master, King Duncan, according to Shakespeare’s play on which the opera is based. Bailey situated this production in the Democratic Republic of Congo to highlight how large international companies exploit the natural resources of the country with the help of greedy rulers. Such exploitation fuels a war in central Africa that continues to cause millions of deaths and hundreds of thousands of refugees. However, the fist also says something about the emerging power of the black South African opera singer who, in South Africa at least, serves as the format’s post-1994 saviour. Yet, just how empowered local black opera singers are in a funding environment unsympathetic to the art form remains an open question.

Sicula iOpera (2018, duration 74 minutes) documents the worldwide tour of Brett Bailey’s adaptation of Verdi’s opera Macbeth and gives glimpses of the lives of the singers for whom opera has become a way of life. As the film’s director Catherine Henegan states, it is ‘a portrait of a project and its players’. The production started in 2014 and after a single performance in Cape Town, toured throughout the world intermittently until 2017, performing at more than thirty opera houses and festivals. Bailey’s production company, Third World Bunfight, lists close to forty reviews and interviews from all over the world on the production. Henegan travelled with the controversial production in the role of company manager, giving her access to the project and its players over an extended period of time. In September 2018, Sicula iOpera was awarded the special jury prize for originality at the Parma International Music Film Festival.

The project

The project is Bailey’s third engagement with Verdi’s Macbeth. As artist, designer and theatre director he produced the opera in 2001/2, in 2007 and again in 2014, successively moving further away from Verdi’s original version by reworking and re-imagining not only the setting, but also the text and the music. Shakespeare’s 1606 play about how corrupted power leads to death and destruction, has since its inception inspired art works of all sorts and Giuseppe Verdi’s opera (composed in 1847) is one of a few works to have an enduring afterlife in Western art music.[1]Verdi’s admiration for Shakespeare resulted in three operas, Macbeth (1847, revised in 1865), Otello (1887) and Fallstaff based on the Merry Wives of Windsor (1893). Throughout his life, Verdi had wanted to write an opera based on King Lear, but this never came to fruition. Sicula iOpera presents a number of layers of engagement with Shakespeare’s story, each time adapted to a particular moment and genre that reflects its context in time.

Verdi composed this opera early in his career during a time that he later in life, famously referred to as his ‘years in the galley’. He was a contract composer in Milan, composing on demand with little freedom or control over his subject, artists or staging. Within fourteen years (1839-1853), he composed 28 operas and he compared such working conditions with ‘slaves who sweated over the oars in Roman ships of old’.[2]Richard Taruskin (2010), ‘Artist, Politician, Farmer’, The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. Volume 3, p. 568. This reality is far removed from the romantic notion, in Western art music at least, of artistic freedom where composers create music untethered to economic or social demands. Verdi’s creative conditions were at the mercy of opera house directors, politicians and a market place that had to draw audiences in order to turn a profit – not so different from how arts production functions today. In fact, Bailey’s setting of this production in the context of the exploitation of the Congo’s natural resources conjures up images of slave-like labour where workers sweat to the demands of a merciless ruler. The degree to which such images reverberate with the working environment in South African opera today comes into focus in the film too, but more about that later.

Contrary to the majority of 19th century opera story lines, Macbeth is not a sentimental love story but one of ruthless politics. In Italy it was known at the time as ‘l’opera senza amore’, the work without love. The story goes as follows: Scottish army general Macbeth receives a prophecy from three witches predicting that he will be king. He and his power-hungry wife, Lady Macbeth, conspire to kill King Duncan and after having done so, accede to the throne. However, in time the duo become overwhelmed with paranoia, fear and rage and kill everyone who may threaten their power, including women and children. Their killing frenzy ends after Banquo, a former friend of Macbeth, kills them.

Lady Macbeth as the ‘evil woman’ lives strongly in the public imagination and Verdi composed a number of important arias for her.

The other famous aria from the opera is the scene where Lady Macbeth’s guilty conscience plays out in her sleep.

Verdi scored Macbeth for twelve principal singers, a large chorus and symphonic accompaniment, all of which is scaled down in Bailey’s production to three soloists and nine chorus members and a small orchestra of ten musicians. Verdi’s three hour opera is also truncated to ninety minutes. 21st century economic realities and the logistics of touring clearly contributed to the need for paring down this large-scale work. Chopping and changing existing repertoire from the Western art music canon was long considered not done and classical musicians are to this day trained to uphold a high fidelity to the composer’s text. The idea of the composer as the ultimate authority in the execution of a musical work is, however, a late 19th century aesthetic invention that was upheld for close to a century. Today musicians have much more freedom, but the hallowed image of the composer still tends to dominate. Bailey has certainly put paid to that idea and his ‘butchery’ of Verdi’s text fits the brutal aesthetic that he aims to portray through this production.

The drastic adaptation of operas from the Western canon into local settings has been a particular focus in South Africa’s post-1994 opera production and provides context to both Bailey’s Macbeth and Henegan’s Sicula iOpera. Most notable here is the Isango Ensemble of Mark Donford-May whose 2006 production (and film) uCarmen e Khayelitsha, after George Bizet’s popular opera Carmen, was extraordinarily successful, touring the world and winning the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Festival in the same year.

Isango continued in this vein ever since with radical re-imaginings either in live performance or in film of, among others, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Zauberflöte,

Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème and Benjamin Britten’s Noye’s Fludde. Other local opera companies that experimented with drastic adaptations include Cape Town Opera, Opera Africa and the now defunct Gauteng Opera.

During Bailey’s earlier engagement with Macbeth in 2001/2 and 2007 he worked with the South African composer Peter-Louis van Dijk. These productions still had large casts but the opera was shortened to 90 minutes and the score was adapted to include saxophones and African percussion instruments such as the djembe and the marimba.[3]No author, ‘Macbeth as you’ve never seen it’. accessed 17 August 2009. This link has subsequently been deactivated. Roos Tuesday 4 August 2020. These earlier adaptations were set in an imaginary African country with Macbeth as a black leader and Lady Macbeth as his white wife, framed in a postcolonial setting.[4]Herman Wasserman. ‘Opera, ‘n onredbare Eurosentriese kunsvorm?’, Litnet. oulitnet.co.za

A 2007 review of the production stated that the opera was ‘not the Macbeth that European audiences have come to expect’[5]‘Macbeth as you’ve never seen it’. and this sentiment has been pushed even further in the 2014 production. The postcolonial setting has now been broadened to include the exploitation of natural resources, the civil war in the Congo and the spate of refugees that resulted from it. Bailey also chose a new composer for the 2014 version, this time the Belgian saxophonist Fabrizio Cassol, who had to reduce the musical forces to twelve singers and ten musicians. A closer look at the technicalities of how Verdi’s score was adapted each time and how each of these productions rendered different musical and political scenarios is beyond the scope of this review, but would be a fascinating study on opera in and of South Africa.

What did Bailey want to achieve through this production and how did he do it? Bailey often grapples with the idea of power, greed and the supernatural in the African context in his work, and he is known never to have shied away from controversy. In this production though, the line between exotification and genuine humanity is paper thin. I felt intrigued by the exaggerated images, shapes and colours that make the production so engrossing, and I could not help but feel a mixture of fascination, disgust, pleasure and revulsion as a black Lady Macbeth, through some exquisite operatic singing, administered her poison to her spineless husband. This while the stereotype of black violence and excess, voiced through opera, is played out on stage. This is all extremely uncomfortable.

Of course, the backdrop to all of this is European extortionist companies, but that evil remained rather obscured by the strength of the visual images. Which, on second thought, accurately reflects how such companies operate, invisibly pulling the strings. However, the stereotyping of black violence in a space that is predominantly frequented by white audiences (i.e. European opera houses) remains problematic for me.

Creating discomfort is often what artists want to achieve through their art and I wondered what the nature of my discomfort was. This too is something that artists may want to achieve and in that sense, Bailey succeeded. But, I am not sure if I know if my discomfort lies with Bailey’s production or somewhere else.

The players

How does Henegan negotiate this ambivalence between exotification and genuine humanity? Sicula iOpera does not question Bailey’s approach and does not engage with any of the issues that the production raises, if anything, Henegan endorses it. As much as Bailey’s production can be described as controversial, Henegan’s film is not. However, it is through her portrayal of the players that we move closer to a sense of genuine humanity.

The people in and around the production are at the heart of the film. Sicula iOpera is isiXhosa for ‘we sing opera’ and from the onset the viewer is drawn into the lives of the three principal singers, on- and offstage. Soprano Nobulumko Mngxekeza (Lady Macbeth), baritone Boikhutso Owen Metsileng (Macbeth)[6]Metsileng’s voice has since then developed into a tenor. Such a change in ‘fach’ is not unusual. and bass Otto Maidi (Banquo) are interviewed during the tour and also in their home environments where they generously share how opera became their lives’ calling and tell of the challenges of being a professional opera singer in South Africa today. The principals are given ample screen time and emerge as convincing protagonists in the film. Slightly in the background we find the chorus members who are interviewed in group formation. They too discuss the internal politics of local opera production and the impact that the lack of sponsorship for opera companies has on their lives. Throughout the film the sense of community among the singers (principals and chorus) is portrayed as a supportive network that carried them through the many days of touring. The convivial and dignified manner in which Henegan portrays the singers is commendable and stands in sharp contrast to the characters they portray in the opera.

Circling out from that, Bailey and Cassol provide a secondary frame in the film focusing on the production itself and Verdi’s music. They sketch the creation process of the production but they are portrayed as professional figures whose personal lives remain off screen. Towards the end of the film, we find a snippet on the No Borders Orchestra from the Balkans that accompanied the singers, and even farther in the background there are two short, yet significant vignettes on 19th century European monarchs that had a conceptual influence on the production. They are Leopold II of Belgium (1835-1909) who, as the constitutional head of Belgium, colonized the Congo in the 19th century and treated the country as his personal property from which he excessively enriched himself. The other is Victor Emmanuel II of Italy whose call for the unification of Italy became closely intertwined with Giuseppe Verdi’s life. Verdi’s surname was an acronym for the slogan used for the unification of Italy and the restoration of the Italian monarchy: Vittorio Emanuele Re D‘Italia (Victor Emmanuel King of Italy). Verdi became a popular composer and public figure at the time and was indeed tightly embroiled in Italian politics. Europeans are thus the creators of the musical work and the adaptations for this production, they control the various environments specific to the film, and are the paying audiences of the production. The singers execute the music with little influence on creation, production, management or reception, an all too familiar pattern in the hierarchy of opera production.

The large number of highly talented and world class black South African opera singers that emerged since the early 1990s has had a significant impact on opera production in the country and their presence has ever since been met with a mixture of puzzlement and delight. The white opera establishment that supported the genre during apartheid have for various reasons welcomed black singers with open arms. Not only is their presence a safer bet with post-1994 funding agencies, the exotic fantasy of this anomaly on the African continent continues to fascinate and entertain, not only in South Africa, but also abroad. The phrase ‘from township to the world stage’ remains a popular way in which the lives of successful black opera singers are reported on in the media. There is however also much genuine and creative renewal that comes with such forces and Bailey’s production of Macbeth would not have been possible in the previous dispensation.

Puzzlement is equally present and manifests itself in various ways. The abundance of extraordinary talented black singers has baffled the opera and scholarly fraternity alike and engagement therewith has up until now been rather tentative. It is as if people, in South Africa at least (and I include myself here), have not yet developed a new vocabulary to talk about it and thus keep falling into old and racist tropes. Public statements by various role players in South African opera production regarding the ‘special quality’ or ‘rich timbre’ that apparently is unique to the black operatic voice has been with us for a while now, but such notions in essence continue the racial profiling of the previous era.

The fact that the black operatic voice has post-1994 accrued positive connotations does not make such profiling less othering. Furthermore, as the singers attest in the film, not everybody is enthusiastic about black singers’ passion for opera. Former Minister of Arts and Culture, Pallo Jordon, will forever be remembered for his antagonism towards this development when he said in 2005 that ‘what tends to happen in South Africa is that when people are speaking about opera they are speaking about European opera, and what it entails is usually teaching African kids to imitate Italians. What’s wrong with the way Africans sing? Why should you teach them to sing like Italians? To make them into imitation whites — and poor imitations as well?”.[7]Celean Jacobson, ‘Disarming cultural weapons, Art’s place in a transforming land’, The Sunday Times, 28 September 2005. Although this statement is reductive and disregards the integrity of the singers and the role of appropriation and transformation in the genre, fifteen years on, such simplified notions continue to plague black singers on a day-to-day basis. Not only are they questioned about why they sing opera, at the same time the lack of funding and support from the public sector is wreaking havoc on the local opera industry.

However, opera can also have a hold on the most staunch of political activists. The combination of anti-European sentiments and a love of opera lives side by side in UCT opera student Slovo Magida who was a student activist in the #FeesMustFall movement in 2015. At the time, he was prosecuted for ‘acts of violence’, which included the burning of paintings that represented UCT’s colonial past.

The financial situation of local opera production (even before the Covid-19 pandemic) is truly dire and interviewees in the film comment on the instability caused by lack of funding in the industry. Except for Cape Town Opera (CTO), local opera companies work on a project-to-project basis, hiring singers only when funds are available, and many cannot even guarantee one production per year. As the film illustrates, singers often have to fall back on other work to make ends meet. Furthermore, international tours have become an indispensable form of income for local opera companies with the result that local productions have endless tours abroad and very few performances at home. Indigenous opera production has ironically morphed into an export product and Bailey’s Macbeth is a prime example thereof.

In 2018 Henegan’s film won the special jury prize for originality at the Parma International Music Film Festival and I was compelled to wonder why. The film is a great story and as a lover of opera and a scholar in the field, I enjoyed it tremendously, but films that tell stories of courage and endurance in unlikely circumstances are staple food for international festivals. My hunch is that opera singers from Africa still retain their exotic flavour for European audiences and for Parma, in the heartland of Italian opera, this African celebration of Verdi is surely original.

Returning to the image of the clenched fist on Owen Metsileng’s head, the question remains whether opera has become a symbol of solidarity and support for black South African opera singers. Are they saluted, and is there unity, strength, defiance and resistance in the industry? I fear not. South African opera production has become a precarious and unreliable business venture and as much as local singers have become popular and accrued excellent international reputations, much work needs to be done at home. It is clear the conceiving of an opera industry in the same way as it has always been done, will not carry the genre through the bumpy road of economic depression caused by Covid-19 or the #RhodesMustFall generation that will manage arts production in the future.

| 1. | ↑ | Verdi’s admiration for Shakespeare resulted in three operas, Macbeth (1847, revised in 1865), Otello (1887) and Fallstaff based on the Merry Wives of Windsor (1893). Throughout his life, Verdi had wanted to write an opera based on King Lear, but this never came to fruition. |

| 2. | ↑ | Richard Taruskin (2010), ‘Artist, Politician, Farmer’, The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. Volume 3, p. 568. |

| 3. | ↑ | No author, ‘Macbeth as you’ve never seen it’. accessed 17 August 2009. This link has subsequently been deactivated. Roos Tuesday 4 August 2020. |

| 4. | ↑ | Herman Wasserman. ‘Opera, ‘n onredbare Eurosentriese kunsvorm?’, Litnet. oulitnet.co.za |

| 5. | ↑ | ‘Macbeth as you’ve never seen it’. |

| 6. | ↑ | Metsileng’s voice has since then developed into a tenor. Such a change in ‘fach’ is not unusual. |

| 7. | ↑ | Celean Jacobson, ‘Disarming cultural weapons, Art’s place in a transforming land’, The Sunday Times, 28 September 2005. |