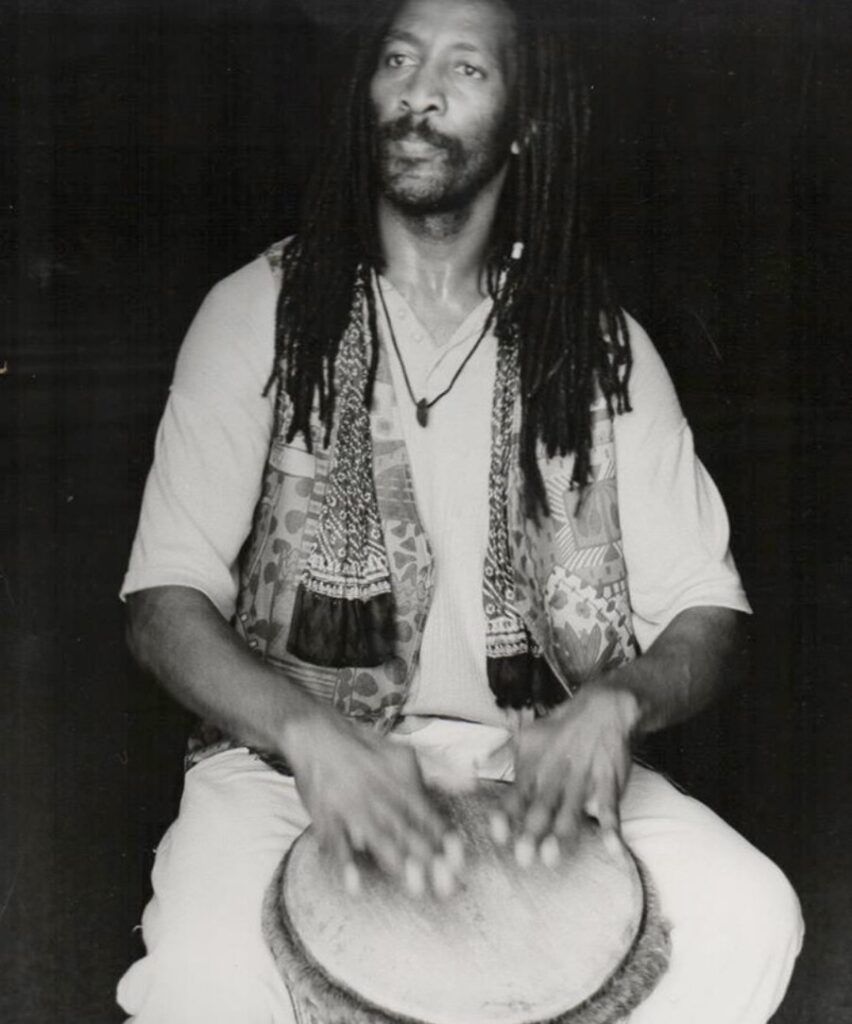

EUGENE SKEEF

Chant of Divination for Steve Biko

I-chant Yokubhula ka Steve Biko

The death of Steve Biko had a profound effect on me. It plunged me into the extended depths of a melancholia that I have spent my whole life ever since trying to tame.

Ukushona kuka Steve Biko kwaba nomphumela ogxilile kimina. Kwangiphonsa ekujuleni kobumnyama esengichithe impilo yami yonke ngizama ukukunqoba.

My close friend Abbey Cindi[1]The renowned South African flautist and co-founder – with guitarist Philip Tabane – of the seminal group Malombo Jazzmen.Usaziwayo ongumdlali we-flute kanye nongomunye wabasunguli – kanye nomshayi wesigingci uPhilip Tabane – weqembu i-Malombo Jazzmen,, came into my bedroom on the morning of 13 September 1977. Perhaps because I had not slept soundly the night before, I woke up instantly and sat straight up. Out of breath and in a state of shock, he proceeded to say, “Steve is nie meer.” He enunciated this statement in the truncated version of Afrikaans prevalent in the black townships whereby the second “nie”, at the end of a sentence, which is a standard double-negative grammatical imperative of the formal language, is stylishly and rebelliously omitted. “Steve is no more.”

Umngani wami omkhulu u Abbey Cindi, weza ekamelweni lami ekuseni ngomhlaka 13 ku Septemba 1977. Mhlambe ngenxa yokuthi bengingalalanga kahle ngobusuku obedlule, ngavuka ngokushesha ngahlala ngaqonda. Ephelelwa umoya futhi ethukile, waqhubeka wathi, ‘USteve akasekho’ (“Steve is nie meer”). Washo lamazwi ngesibhunu esifushane esijwayelekile emalokishini abamnyama lapho u’nie’ wesibili, ekugcineni komusho, okuyindlela yokubonisa ukuphika ngokolwimi olusemthethweni, ushiywa njengesitayela futhi ngendlela yokuvukela ulahlwe. “USteve akasekho” (Steve is no more).

Biko died on 12 September 1977, alone in a cell in a prison hospital in Pretoria. A few days before that he had sustained extensive brain injury as a result of being brutally beaten by Afrikaner security police officers during interrogation in the infamous Sanlam building in Port Elizabeth, before being transported, naked and in chains, in the back of a Land Rover for 740 miles to Pretoria[2]In February 1973 I had been at the wheel of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) VW Kombi, with Biko in the passenger’s seat next to me, when we were escorted by the Security Branch to that same building, which served as their Eastern Cape headquarters, for the principal anti-apartheid activist of the time to be handed his five-year banning order. NgoFebruwari 1973 ngangishayela imoto ye South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) okuyi VW Kombi, uBiko wayehleli esihlalweni sabagibeli eceleni kwami, masesilandelwa iSecurity Branch sibheke kulelobhilidi, nelalisebenza njengekomkhulu lase Eastern Cape, ukuze lomgqugquzeli wezepolitiki olwisana nobandlululo ezothola incwadi yeminyaka emihlanu i-banning order..

UBiko washona ngo 12 Septemba 1977, eyedwa ekamelweni lasesibhedlela sasejele ePitoli. Ezinsukwini ezimbalwa ezedlule wayelimale kanzima engqondweni ngenxa yokushaywa ngamaBhunu angamaphoyisa ngesikhathi emupheka ngemibuzo endaweni eyase yaziwa kakhulu ibhilidi i-Sanlam elise Port Elizabeth, ngaphambi kokususwa, engagqokile futhi eboshwe ngamaketanga, ngemuva kwi Land Rover lapho bahamba 740 wamamayela ukuya ePitoli.

Since the day of Biko’s murder I have nurtured an augmentation of a private pain pulsing deeply within my heart, pruning it with the shears of my music, poetry, art and theatre. For it has made sense for me to cultivate its flourishing in the garden of my soul, because the presence of pain is a spot-lit reality in all our lives. Pain is the salt that flavours our every experience so that we may savour the fulness of life. Hiding pain beneath layers of pretence can lead to an incomplete fruition of life’s attainments and to an adverse state that I refer to as being dead alive.

Kusukela osukwini lokubulawa kukaBiko senginakekele ukwengezwa kobuhlungu engibuzwa ngedwa ngaphakathi enhliziyweni yami, ngibuncwela ngibuphuca ngomculo wami, izinkondlo, ezobuciko kanye nemidlalo yase-steji. Kwenza umqondo kimina ukuhlumelisa engadini yomphefumulo wami, ngoba ukuba khona kobuhlungu kukhanya bha ezimpilweni zethu. Ubuhlungu usawoti ononga isipiliyoni ukuze sinambithisise impilo ngokugcwele. Ukufihla ubuhlungu ngaphansi kongwengwezzi lokuzenzisa kulandela ekutheni impilo ingabi egcwele nokunqqoba empilweni kungagcwalisekisisi kanye nesimo esiphikisayo engisibiza ngokuthi ukuphila ufile. (being dead alive).

And so I have learned to live as creatively and with as much fulfilment as I can with the burden of my particular brand of sensitivity. This recognition of my deeper self ignited my peculiar understanding of the meaning of freedom, which has accompanied me throughout my cultural work. I came to know that all creativity is a sacrificial act of love.

Ngakho ke sengifunde ukuphila ngokudala (creatively) kanye nokweneliseka ngendlela noma nginomthwalo ofana nalona kanye nozwelo. Ukuqonda lokhu kujula okukimina kususe ukuqonda okuthize kimina ngencazelo yenkululeko, osekuhambe nami impilo yami yonke emsebenzini wezobuciko namasiko. Ngigcine sengazi ukuthi ubuciko buwumhlatshelo wesenzo sothando.

The profoundly painful personal impact of Steve’s death on me is rooted in a cardinal experience that took place during our student days in the early seventies. Every step I have taken since the day I learned that I was targeted as an informer has been a determined stride towards the destination of my healing.

Ubuhlungu obukhulu obuphathelene nokufa kukaSteve kimina bunezimpande kwisipiliyoni esenzeka ngesikhathi sethu sisengabafundi ekuqaleni kweminyaka yama-seventies. Wonke amanyathelo engiwathathile kusukela ngosuku engafunda ngalo ukuthi ngangiqondiwe njengempimpi sekube indlela ebheke ekwelaphekeni kwami.

Even in the earliest stages of the emergence of this strangling weed in the garden of my innocence, I became acutely aware of a profound and exquisite vibration deep within my consciousness. I was delivered by this negative charge that sought to consume my whole being to a place within my psyche where there resided an oracular pulsing presence that began to germinate and grow like one of those seeds that are trapped under a heavy rock but somehow still manage to communicate their inherent greenness to the sun hiding behind dark clouds. I transcribed this resolve into a silent mantra that I sang to myself from the moment I became aware of these unstoppable inner tides. I knew from that early moment that the accusatory arrows aimed at my heart would bless me by deepening the wound from which would flow forth the gifts of the healing work I was destined to do in this world.

Ngisho ekuqaleni kwalolukhula oluklinyayo engadini yobumsulwa bami, ngibe sengibona kunobunzulu kanye nokuzamazama phakathi emqondweni wami. Ngakhululwa ilamandla aphikisayo nayefuna ukungidla angiqede endaweni esemqondweni lapho kuhlala khona umdumo owedlula ukuba khona owaqala ukuhlumela nokukhula njengalezo zimbewu ezibambeke ngaphansi kwetshe elisindayo kodwa ngandlelathize ikwazi ukuxhumana nobuhlaza nelanga elicashe ngemuva kwamafu amnyama. Ngayidlulisela lento ekubeni yi-mantra yokuthula engiziculela yona kusukela ngalowomzuzu ngibona ukuthi nginalamagagasi angavimbeki ngaphakathi. Ngangazi kusukela ngaleso sikhathi ukuthi imicibisholo yezinsolo ebhekiswe enhliziyweni yami izongibusisa ngokujulisa isilonda okuphuma kuso izipho zomsebenzi wokwelapha engimele ukuwenza kulomhlaba.

Whenever I was in a public gathering I would look at people as they approached me and wonder if they knew, and if they knew, what they thought. Just to add quickly that the super irony of my experiences at the hands of people who tried to cease my breath is that in my time with Biko I was the most relied upon to complete missions without getting caught by the Special Branch, while those who who targeted me chanted slogans and waved their cleched fists and couldn’t wake up the next day from being hungover. I was never caught once on these missions, many of which I accomplished while on a fast and having done one hundred one-finger press-ups and extreme yoga. I used to drive at over 120 MPH in getaways, with Steve by my side (I was taught to drive at 9 years old by my father, who was the toughest task master I’ve ever had)…

Njalo lapho ngisendaweni lapho kuhlangene khona umphakathi bengiyaye ngibuke abantu khathi beza ngakimi ngizibuze ukuthi ngabe bayazi yini, futhi uma bazi, bacabangani.

Ukwengeza nje ngokushesha lendida kazi yesipiliyoni sami ezandleni zabantu abazama ukungikhipha umoya ukuthi esikhathini sami noBiko ngangiwuyena muntu othembekile ekutheni uyawuqeda umsebenzi awunikiwe ngaphandle kokubanjwa i-Special Branch, ngenkathi labo ababengiphokophelele becula iziqubulo futhi bephakamisa izingqindi futhi bengakwazi ukuvuka ngosuku olulandelayo ngenxa ye-hangover. Angikaze ngibanjwe nakanye ngikuma-missions, amaningi awo engawaqeda ngizile ukudla futhi ngishaya ‘one hundred one-finger press-ups’ kanye neyoga enzulu. Bengijwayele ukuhamba ngo 120MPH uma sibaleka, no Steve eceleni kwami (Ngafundiswa ukushayela ngina-9 weminyaka ubaba wami, nowayeqotho kunabobonke ekubhekeni imisebenzi esengake ngaba naye)…

Aside from the profusion of love that I have been showered with by my family and friends, no experience in my entire life has exercised so powerful and lasting an impact on me as being accused of being a sell-out, spy, informer or, as we say in the Zulu language, impimpi. But I have borne the painful excoriation with the dignity of the sweetest possible melody that is produced by the steel pan from the indentations in the wrought metal of discarded oil drums after severe hammering into the shape of the resilient note.

Ngaphandle kobuningi bothando engilunikwe umndeni wami kanye nabangani, asikho isipiliyoni empilweni yami yonke esithinte ngamandla futhi sashiya umphumela kimina njengalesi sokubhecwa ngokuthi ngingumdayisi, inhloli, impimpi noma, njengoba sisho ngolwimi lwesiZulu, impimpi. Kodwa ke sengithwale ukuhuzuka ngenhlonipho yomculo omndandi kunawo wonke ophuma kucwephe lensimbi olushawa insimbi evela ezigubhini zika-oyela emva kokushawa kakhulu zize zibe sesimweni senothi elizimele.

It was a known strategy of the Security Branch to accuse student activists of being informers. This strategy succeeded, to a limited degree, in inflicting fractures in our movement, resulting in some of us pointing fingers at each other and thereby reducing our effectiveness at undermining the apartheid state. This was a manifestation of the age-old oppressor technique of divide-and-rule, which had the effect of opening up more and more fissures of betrayal among some of us that dissipated and diverted our energies and focus from the real cause of our struggle. More and more we witnessed a culture of suspicion penetrate our ranks.

Kwakuyicebo elaziwayo le-Security Branch ukusola abafundi abangabaholi ngokuba izimpimpi. Leli qhinga belisebenza, ngokulinganisekile, beliwuqhekeza umbutho wethu, lokhu bekugcina ngabanye bethu bekhomba iminwe kwabanye lapho ke kwehla nezinga lokusebenza umsebenzi wokuphazamisa uhulumeni wobandlululo. Lokhu kwakuwukusebenza kweqhinga elidala labacindezeli elibizwa nge divide-and-rule, lokhu kwakunomphumela wokuthi kuvuleke uqhekeko olubangwa ukukhaphelana phakathi kwabanye bethu lokhu bekuqeda amandla ethu futhi kusisuse kwinhloso nakumsusa womzabalazo. Ngokuya ngokuya sibone isiko lokusolana lingena embuthweni wethu.

I wonder if I too was a target of this nefarious strategy. I still don’t know how to interpret the Special Branch agent’s strange unfounded reference to me in my comrade Sam Moodley’s reminiscence below.

Ngiyazibuza ukuthi ngabe nami ngangiqondwe ileliqhinga lobubi. Angikakazi ukuthi ngiyihumushe kanjani indaba yendoda ye Special Branch yokukhuluma ngami ku-khomrade Sam Moodley ngokukhumbula kwakhe lapha ngenzansi.

INTERROGATION

UKUPHEKWA NGEMIBUZO

All was quiet at the BCP (Black Community Programmes) offices on the morning of 3 March 1973. Business as usual you would say. The TECON (Theatre Council of Natal) van had left taking Harry Nengwekhulu, Steve Biko, Ben Langa with Eugene at the helm. Not much fuss as the guys left on their national visits to universities beginning their first leg of the journey to Ngoye University (now known as University of Zululand).

Konke bekuthule emahhovisi e BCP (Black Community Programmes) ngomhlaka 3 Mashi 1973. Konke bekuhamba ngendlela njengoba kuye kushiwo. Iveni ye-TECON (Theatre Council of Natal) beseyiphumile no Harry Nengwekhulu, Steve Biko, Ben Langa no Eugene njengomshayeli. Kwakungenzima ngoba babeqala uhambo lwabo lukazwelonke lokuvakashela amayunivesithi beqala ngomlenze wabo wokuqala waloluhambo oNgoye University (manje eyaziwa nokuthi i-University of Zululand).

The phone rang incessantly. No one else being there I had to answer the call. A deep voice with an Afrikaner accent asked boldly, “ Can I speak to Eugene Please?

Ucingo lwakhala lwangaqeda. Engekho omunye okhona kwafanele ngiluphendule. Izwi elibanzi elinesigqi sesiBhunu sabuza ngokuzethemba, “Ngingakhuluma noEugene Ngiyacela?”

“He’s not in,” I answered.

“Akekho,” ngaphendula.

“What time is he expected?” The voice was brash and rough.

“Ulindelwe ukubuya nini?” izwi lizwakala lingenasikhathi futhi lingacoyisekile.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “Who’s calling ?”

“Angazi,” ngaphendula. “Ubani obuzayo?”

“Tell him it’s Welman… Captain Welman… He has my number.” And the call went down…Silence…

“Umtshele ukuthi u Welman…Ukaputeni Welman…Unayo inombolo yami.” Ucingo lwavaleka…Kwathuleka…

A million thoughts went through my confused mind. Why would he ask for Eugene? Does the Special Branch know about the trip to Ngoye?

Isigidi semicabango yaya enqondweni yami eyayivele ididekile. Kungani efuna u Eugene? Kungabe i Special Branch siyazi ngohambo lwasoNgoye?

That afternoon the Special Branch swooped on the SASO offices and the first of the Banning Orders was handed to Strini as they removed him from the premises stating that he would be arrested if found to be physically present there.

Ntambama iSpecial Branch satheleka emahhovisi eSASO aqala ukukhipha ama-Banning Orders ewanika u-Strini ngenkathi bemukhipha ezakhiweni bemutshela ukuthi uzoboshwa uma engatholakala elapho.

Later we heard that seven others were banned and sent to their “homelands”. Apparently Steve and Harry were given their “papers” while on the trip.

So what of Eugene Skeef?

Ngokuhamba kwesikhathi sezwa ukuthi abanye abayisikhombisa baxoshwa babuyiselwa kuma ‘homelands’.

Kungathi u Steve no Harry banikezwa amaphepha abo besekulo uhambo.

Kwenzekani ngo Eugene Skeef?

I don’t recall what had happened to the van in which they travelled to Ngoye. In the following few days Eugene visited the office and I remember telling him about this suspicious call on that fateful day that changed our lives at 86 Beatrice Street.

Angikhumbuli kwenzekani kwiveni abahamba ngayo ukuya oNgoye.

Emalangeni alandelayo uEugene wavakashela emahhovisi futhi ngiyakhumbula ngimtshela ngocingo olusolisayo ngaleliyalanga nolwashintsha izimpilo zethu e 86 Beatrice Street.

So on the 25th March when I was arrested by the Special Branch after the Sharpeville Memorial Commemoration at the University of Natal Black Section(UNB), in the interrogation room where I was placed in a kneeling position for 4 hours, I was asked, “Who was at the meeting ?”

Ngakhoke ngomhlaka 25 kuMashi mangiboshwa i-Special Branch ngemva kwe Sharpeville Memorial Commemoration e-University of Natal Black Section (UNB), endlini yokuphekwa ngemibuzo lapho ngabekwa ngiguqile amahora amane, ngabuzwa, “Ubani owayesemhlanganweni?”

My mind raced trying to remember names and faces. “Come on, talk up ! Talk up !”

It was Captain Welman who persisted with the questions. Memory of the phone call on the fateful day of 3rd March flashed vividly… his voice… “he has my number” echoed clearly and, wanting to play his game, I said “Eugene Skeef.”

Ingqondo yami yaqijima izama ukukhumbula amagama nobuso. “Yenza, khuluma! Khuluma!”

Kwakungu Kaputeni Welman owayengipheka ngemibuzo. Ukukhumbula ucingo lwangalelilanga elinzima lomhlaka 3 Mashi kwadlula enqondweni…izwi lakhe…”unayo inombolo yami” ngezwa ngokucacile, ngifuna ukudlala umdlalo wakhe, ngathi “Eugene Skeef.”

“Was he the only one ? Who else ?” I still said “Eugene Skeef.” My interrogators exchanged glances, sharp piercing eyes squinted at me, heads shook. The interrogation continued.

“Kwakuwuyena kuphela? Ubani omunye” Ngaphinda “Eugene Skeef.”

Ababengipheka ngemibuzo babukana, amehlo ahlabayo angijeqeza, banikina amakhanda. Baqhubeka ngokungipheka ngemibuzo.

The national tour that Sam refers to of black universities to conscientize students kicked off at Alan Taylor Residence in Wentworth, Durban, where I had earlier witnessed Steve Biko’s charisma and eloquence for the first time in public. The occasion was a student rally that was held in the main hall on campus. I remember distinctly, as if it was only yesterday, hearing a resonant voice coming from the right back corner of the hall in response to a statement that someone on stage had made. The entire hall turned round to see who the owner of the voice was. It was Biko. That proved to be a major turning point in my life. There would be no looking back after that.

Uhambo lukazwelonke akhuluma ngalo uSam olwamanyuvesi amnyama ukuyogqugquzela abafundi lwaqala e-Alan Taylor Residence e-Wentworth, eThekwini, lapho ngabona khona okokuqala isiphiwo sokuthandeka nokugagu buka Biko okokuqala emphakathini. Lomcimbi kwa kuyi-rally yabafundi futhi yayibanjelwe ehholo elikhulu ekhampasini. Ngikhumbula kahle, kungathi bekuyizolo, ngizwa izwi elishukumisayo liqhamuka ngakwesokudla ekhoneni elisemuva nehholo liphendula owayekade ekhuluma esteji. Ihholo lonke laphenduka ukubona ukuthi ubani umnikazi walelozwi. Kwakungu Biko. Lokhu kwaba iphuzu elinoshintsho kakhulu empilweni yami. Kwakungasekho ukubheka emuva emva kwalokho.

I consider myself to be very fortunate, and in many ways blessed, to have known Steve Biko closely. The brief relationship that blossomed between us was toned by a spiritual resonance of a kind that exists only in an environment of love, respect and the florescence of humanity. Three dimensions of this relationship are indelibly inscribed in the temple of my deepest memories. One is the experience of drawing the first ever South African version of the clenched fist symbol of Black Consciousness in Steve’s presence at Alan Taylor Residence for Black students; the second is the exhilaration of driving him when we were being chased by the Special Branch; and the third is the everlastingly profound sadness of his death, which has enveloped me ever since that terrible moment and continues to propel my breath with a meditative pulse.

Ngizibone njengomuntu onenhlanhla, ngezindlela eziningi obusisekile, ukwazana no Steve Biko eduzane. Ubungani obufushane obabuphakathi kwethu babunomthelela wokomoya ngaloluhlobo olutholakala kuphela endaweni enothando, inhlonipho kanye nokuhluma kobuntu. Izinhla ezintathu zalokhu kuzwana zilotshiwe ngaphakathi kimina njengezinkumbulo. Okokuqala umuzwa wokudweba okokuqala eNingizimu Afrika isandla esifingqe iqupha njengomfaniso we Black Consciousness kukhona uSteve Biko e-Alan Taylor Residence lapho kuhlala khona abafundi abamnyama, okwesibili ukushisa komzimba lapho ngishayela imoto enaye uma sibalekela i Special Branch; okwesithathu ukudumala okungapheli ngenxa yokufa kwakhe, nosekungibambe seloku kwenzeka futhi kuyaqhubeka nokungenza ngijule ngakho.

So it must have been in 1973 that Steve was addressing a gathering of students at what we called Res at the launch of the tour of universities. The hall was packed to capacity again, with roused students raising clenched fists as they chanted Black Power slogans.

Kwenzekake ukuthi ngo 1973 u-Steve wayekhuluma nabafundi ababehlangene kulokhu esasikubiza ngokuthi ama-Res ngesikhathi siqala uhambo lwamayunivesithi. Ihhlolo laligcwele phama futhi, nabafundi ababephakamisa izingqindi zabo bememeza neziqubulo zamandla amnyama.

At the end of the speeches students emptied out onto the lawn and gathered in small groups of heated discussion inspired by the words of Biko. One of the groups on the lawn under a clear blue sky was gathered around a man they had dragged from the hall. He was of medium build and dressed in a button-down Ivy League American shirt, Levi’s jeans and dark brown shoes that looked like fashionable Doc Martens. His mistake was to not have been recognised as one of the students by the group that surrounded him, and to have attended the rally wearing brand new pleated jeans and shoes that resembled the supply footwear for officers of the South African Police. These features of his apparel were a sure giveaway to his attackers who were accustomed to it being more acceptably fashionable for students to wear jeans that were worn and faded, and American Converse All-Star trainers, or what we called amateku/tekkies in hip township ghetto parlance.

Emva kwezinkulumo abafundi bahlangana etshanini ngamaqoqo amancane bedingidisisa inkulumo esuswe amazwi kaBiko. Elinye lamaqoqo lalihlangene lingunge indoda ababeyihudule beyikhipha ehholo. Wayethi akabe phakahi nendawo ngobude egqoke okunezinkinobho okwaziwa nge Ivy League American shirt, udangala weLevi’s kanye nezicahulo ezinsundu ngokumnyama ezazibukeka njengama Doc Martens ayesemfeshinini. Iphutha lakhe kwakuwukungabonakali njengomfundi kulabo bafundi ababemngungile, nokuza kwi-rali egqoke odangala abasha kanye nezicathulo ezibukeka njengomfaniswano wamaphoyisa aseNingizimu Afrika (South African Police). Lezizingubo zakhe yizo ezamveza kubahlaseli bakhe ababejwayele ukuthi abafundi bagqoka odangala asebebadala nasebephuphile, kanye namateku i-American Converse All-Stars, noma lokhu esikubiza ngamateku/tekkies ngolwimi lwase-ghetto.

The guy was forcefully frogmarched to the nearest room, which belonged to one of my close friends. Along the way one of the worked-up mob picked up a strewn sharp-edged brick from the lawn and chanted some fiery slogan to endorse the man’s impending doom. The accused was shoved into the spartan room containing a small table and chair against the whitewashed brick wall, a little wardrobe, modest bookshelf and a single coil-sprung bed along the side wall. A pungent premonition immediately filled the ceiling-less room making the air feel even more compressed by the low corrugated asbestos roof. Once everyone was inside, the door was locked and the jaded curtains drawn. With the man on his knees in the middle of the floor, and everyone crowded around him, there was no room to move. Some of us had to stand on the bed and get onto the table. Then the student holding the brick took the lead and used it to bash the wailing man’s tear-soaked face. The brick was passed around the circle from one person to the next to administer their share of mob justice to a man who none of us could say with any certainty was a police informer.

Lomlisa waphoqwa ukugxumisa okwesele ebheke endlini eseduzane, okwakuyindlu yomunye wabangani osondelene nami. Endleleni omunye walabafundi abadiniwe wathatha isitini esihlephukile etshanini wamemeza iziqubulo ezivusa uhlevane ebhekise kulendoda eyayisibhekwe ukushabalala. Umsolwa wahlohlelwa kulendlu encane eyayinetafula kanye nesihlalo nombhede wezi-pringi ngasodongweni. Ukusola okuzayo kwagcwala kulendlu eyayingenasilingi kwenza umoya uzwakale ucinene ngenxa kabhestazi owawuseduze wophahla. Kwathi sekungene wonke umuntu, umnyango wavalwa kwadonswa namakhethini. Lendoda yase iguqe phakathi nendlu, wonke umfundi ongaphakathi esondele kuyona, yayi ngekho indawo yokunyakaza. Abanye bethu kwafuneka ukuthi sime embhedeni abanye etafuleni. Kwathi lomfundi owayephethe isitini waqala washaya lendoda ebusweni obase bugcwele izinyembezi. Lesi sitini sadluliselwana kulesekele sisuka komunye siye komunye ukuze naye ashaye njengoba sekushaywa lendoda okwenkantolo yasehlathini esasingeke sisho ngokugcwele ukuthi uyimpimpi yamaphoyisa.

In seconds the man’s face was unrecognisably disfigured and covered in blood. The blood from the pounding splattered onto us and stained every surface of the cramped room. When the brick was passed to me, indicating that it was my turn to add blows to the unconscious victim’s face, I remained still and did not stretch my hand out to receive the bloody weapon, to the consternation of everyone else, whose faces froze into sterile stares.

Ngemizuzu nje emibalwa ubuso balendoda base bungabonakali futhi bugcwele igazi. Igazi elaliphuma uma eshaywa lase ligcwele kithi futhi selingcolise indlu eyayigcwele ichichima. Uma lesi sitini sifika kimina, sikhombisa ukuthi isikhathi sami sokushaya lendoda eyayingasabonakali nobuso, ngama ngathi dlengelele angaselula isandla ukuthatha isitini esinegazi, lokhu kwacasula wonke umuntu, ubuso babo bamangala bangibheka ngokudinwa.

That day a man’s fate was determined by the whipped up emotions of a group of young students who drew unsubstantiated conclusions on the unfortunate basis of his unwittingly misguided attire.

Ngalelolanga impilo yendoda yabekwa emizweni yeqeqebana labafundi abancane abazikhethela ukukholwa abakufunayo ngenxa yezingubo zokugqoka.

Many years later, when I was in exile in London, two events would bestow my wounded soul with a redemptive cadence.

Eminyakeni eminingi elandelayo, lapho ngisekudingisweni e-London, izehlakalo ezimbili zabuyisela umoya wami endleleni.

At the height of the struggle against apartheid, the top South African spy Craig Williamson’s cover was blown. A book as fat as he was published revealing details of the dirty secret work of the Security Branch, much of which had links to the vast and complex networks of political activists like myself. Everyone in my circles rushed to buy Inside BOSS by Gordon Winter to see whose names were revealed in what was regarded at the time as the definitive exposé of the nefarious techniques of the South African security police agents (BOSS was the acronym for Bureau of State Security). I remember a group of my closest comrades gathering at my place to share red wine while discussing the forensic details of this who’s-who of state collaborators. My relief at the vindication of my sullied name was palpable.

Ekulwisaneni nobandlululo, inhloli enkulu yaseNingizimu Afrika u-Craig Williamson wakhishelwa obala. Incwadi eyayikhuluphele njengaye yakhishelwa ukuthengisa iveza wonke amawunguwungu omsebenzi we -Security Branch, omningi wawo owawunokuxhumana nenxanxathela yezindlela sosopolitiki abangabagqugquzeli abafana nami. Wonke umuntu eduze kwami wagijima wayothenga i-Inside BOSS ka Gordon Winter ukuzibonela lawo magama abantu aveziwe nokwakuyisikhathi sokuvela komsebenzi wokungcola kwamaqhinga enhlangano yezokuphepha eNingizimu Africa (BOSS imele ukuthi Bureau of State Security).

Ngiyakhumbula iqeqebana labangani bami behlangana endaweni yami ukuzophuza iwayini elibomvu sibe sidingida imininingwane yobani nobani ababesebenzisana nohulumeni wobandlululo. Ukukhululeka kwami ngokugezeka kwegama lami kwakungabambeka.

The second event transpired in the nineties at the home of the comrade in whose student room the tragic reconstitution of the unfortunate man had taken place. He had been posted to London by the African National Congress (ANC) to coordinate the cultural prelude to Nelson Mandela’s imminent release from prison and preparation for his preordained presidency. One evening he invited my family to his home for dinner. After a sumptuous meal and sharing of stories from our past, he produced a novel he had written and read part of a chapter to the quiet table detailing a crucial dramatic moment involving the principal protagonist. I was moved to tears by what was clearly a story inspired by that fateful event, in which my courageous act had stayed with my friend all those years while he was in exile in another country where he was involved in the armed struggle for our liberation. He signed the book with revelatory candour and handed it to me.

Isigameko sesibili senzeka ngama-nineties ekhaya lomunye wama khomrade okwakusendlini yakhe njengomfundi lapho kwashayelwa khona leya ndoda.

Wayesethunyelwe eLondon umbutho i-African National Congress (ANC) ukuze ahlanganise izindibano zamasiko ukwendulela ukukhululwa kuka Nelson Mandela ejele nokulungiselela ukuya kwakhe esikhundleni somumongameli. Ngobusuku obunye wamema umndeni wami ukuzodla naye isidlo sasebusuku. Emva kokudla okwehla esiphundu kanye nezindaba zakudala, wakhipha incwadi (novel) ayeyibhalile wafunda isigaba esithize esasifaka umlingiswa oqavile. Ngezwa ngifikelwa izinyembezi ngalokhu engakubona kususelwa kulesosigameko, lapho isibindi sami sahlala khona nomngani wami yonke leyo minyaka esekudingisweni kwelinye izwe lapho ayelwela inkululeko yalelizwe. Wasayina lencwadi ngokuzithoba okuqotho wanginikeza yona.

The partition between acts of compassion and aggression is infinitely thinner than the cement that holds together the parallel bricks in a standing wall that divides the security of an enclosure from the threat of the world outside. But in truth there are wildernesses on either side of these fundamental symbiotic human qualities, just as in the dividing wall.

Ukwehlukanisa phakathi kozwelo nesihluku kuncane kakhulu kunosimende obamba uhlanganise izitini obondeni olwehlukanisa ukuphepha kanye nokwesabiswa komhlaba ongaphandle. Kodwa eqinisweni kunokudlova nxazonke kanti lokhu kuyisakhiwo somuntu, njengoba kunjalo nasodongeni.

The rumour of me being an informer nearly cost me my life. I became aware of at least a couple of attempts to erase me from the face of the earth. My vigilance intensified, but I tried as much as possible to never let it show that I felt targeted. The irony of my situation was that I ended up fearing the possibility of an untimely death by the hands of my own comrades more than by the brutal agents of the apartheid regime. This fear was so real that without thinking I found myself gradually receding from open association with my comrades in the Black Consciousness Movement.

Amahlebezi okuthi ngiyimpimpi acishe angephuca impilo yami. Ngiyazi ngemizamo emibili yokuzama ukungisusa lapha emhlabeni. Ukuzibheka kwami kwaya ngokuqina, ngazama ngakho konke okusemandleni ukungakhombisi ukuthi ngangiwohlosiwe.

Isimanga salesisimo sami ukuthi ngagcina ngesaba ukuthi ngigcine ngifa kabuhlungu ezandleni zama-khomrade kunezandla zesihluku zikahulumeni wobandlululo. Lokhu kwesaba kwakunzima kakhulu kangangokuthi ngagcina ngihlehla ekuhlanganyeleni nama-khomrades kwi-Black Consciousness Movement.

This is the fear that kept me away from Steve Biko’s funeral, an omissive omen that would follow me into exile in 1980, and that to this day still weighs heavily on my conscience. It is like a mist that descends on me periodically, but which I consistently lift into the open skies of my cultivated self-belief through the redemptive and transformative powers of my creative work. Meditation, music, movement, poetry and every aspect of my creative expression combine to cleanse me of that contamination of being wrongly accused of being a collaborator.

Ilokhu kwesaba okwenza ngingayi emngcwabeni kaBiko, ukungenzi okwangilandela ngisho ekudingisweni ngo 1980, lokhu nanamhlanje kusangisinda engqondweni. Kufana nenkungu eyehlela kimi ngezikhathi, kodwa engiyiphakamisela esibhakabhakeni esivulekile ngokuzethemba emsebenzini wami wokuzakha nokuzikhulisa ngamandla omsebenzi wobuciko. Ukujula, umculo, ukunyakaza, izinkondlo kanye nayo yonke indlela yokuzibonakalisa kuyahlangana ukungigeza kulokho kungcoliswa kokubhecwa ngecala lokuba umdayisi.

My ability to overcome a fear of immeasurable proportions has developed over the decades into a technique that I have incorporated into my creative workshops. Even as I type I can hear the voices of those close to me who share the intimacies of my story. The corpuscles of my pain pulse in their blood as well because that is the nature of true friendship and family and what it means to have comrades. My mother carried the pain of her first-born’s accusation to the grave like an inverted inheritance. The recently passed radical activist Rubin Hare, who was once Vice President of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) and my fellow student at the University of the Western Cape where we were activists together, was a true comrade and friend. From day one he never accepted that I could be an informer. He stood firmly in his belief of my innocence, often challenging me for accepting those in our movement who perpetuated the rumour back into our circle of trust.

Ukukwazi kwami ukunqoba ukwesaba okungaka kukhule kanye nesikhathi neminyaka kwagcina sengikusebenzisa emsebenzini wami wokuqeqesha kwezobuciko. Ngisho ngibhala lapha ngisawezwa amazwi alabo ababesondelene nami ababelwazi kahle loludaba. Imivimbo yobuhlungu igijima egazini labo ngoba bunjalo nje ubungani beqiniso nomndeni kanye nokuba nama-khomrades. Umama wami wathwala ubuhlungu bokusolwa kwendodana yokuqala yakhe waze wayongena ethuneni njengefa elihlanekezelwe. Umgqugquzeli osanda kushona u Rubin Hare, owake waba nguSekela Mongameli we South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) nowayefunda kanye nami e-University of Western Cape lapho sasingabagqugquzeli ndawonye, wayengumngani weqiniso kanye neqabane.

Kusukela ngosuku lokuqala akazange amukele ukuthi ngingaba impimpi. Wama wamisisa ekukholweni ukuthi ngangimsulwa, wayengilwisa ngokwemukela labo embuthweni ababelokhu bebuyisa lendaba esigungwini sethu.

My pain resurfaced as I seriously considered returning permanently to South Africa. I wondered if there were still remnants of the story littering the memories of some people. This is when I thought of asking Rubin to write me a reminiscence of a crucial moment in our comradeship towards my further vindication. When I recently decided to contact Rubin again to request his written reminiscence so that I could insert it in this chapter, I was told by his daughter Imaan Hare that he had left this world two days before that.

Ubuhlungu bami babuya ngesikhathi ngicabanga ukubuyela eNingizimu Afrika. Ngazibuza ukuthi kungenzeka yini ukuba kusenezinsalela zaloludaba ezingqondweni zabanye abantu. Ilapho ngacabanga ukucela khona u-Rubin ukuthi abhale sakukhumbula izinsuku ezadlula ngalesisigameko esibalulekile ngobuqabane bethu ukuze ngigezeke. Ngithe uma sengikhetha ukuxhumana no-Rubin futhi ukuze ngimcele abhale sakukhumbula ukuze ngifake leyombhalo kulombhalo, ngatshelwa indodakazi yakhe u-Imaan Hare ukuthi ubese enezinsuku ezimbili edlulile emhlabeni.

After decades of not being able to put my finger on who exactly the person was who initiated the terrible accusation that sparked the rumour, the answer was providentially delivered to my laptop screen. In 2020 I opened a Facebook link to an online newspaper article paying tribute to Doctor Zama Norman Dubazana who had recently passed on. The tribute celebrated his achievements as a Bergville-born political activist who was once the SASO Publications Director. I had forgotten Dubazana’s name, but immediately recognised his handsome face from the photo that accompanied the article.

Emva kweminyaka engamashumi ngihluleka ukubona ukuthi ungabe ubani lomuntu owaqala ukungibheca nowasusa lamanga, impendulo yangena kwi-laptop yami. Ngo 2020 ngilandele isixhumaniso saku-Facebook esangiyisa ephepheni eli-online elalinendatshana lihlonipha u Doctor Zama Norman Dubazana owayesanda kudlula emhlabeni. Loludaba lwaqhakambisa izenzo zakhe njengomgqugquzeli ozalwa e-Bergville nowake waba i-Publications Director ye-SASO. Ngase ngilikhohliwe igama lika Dubazana, kodwa ngabubona ubuso bakhe obuhle esithombeni esasihamba nalendatshana.

The image took me back to our youth with lightning speed! I had a vivid visualisation of us in meetings with Steve Biko during the early days at Alan Taylor Residence. Then it all began to make sense! Dubazana is probably the person who started the unsubstantiated rumour that I was an informer. I recall him being present during the attack on the man who was suspected of being a police informer. The certainty of my feeling about this memory is rooted in the particularities of the relationship I had with Norman during our time at Alan Taylor. I associate this with the extreme coldness that he began to exude towards me soon after the incident of the brick-bashing in our comrade’s room. This inexplicably swift freezing of our relationship confounded me at the time, especially given that we were always close, united also by our love of martial arts and fitness, which we tried to get my close friend Ben Langa to take an active interest in.

Lomfanekiso wangithatha wangibeka ezikhathini zethu sisebancane ngokushesha! Ngakhumbula kahle sisemihlanganweni no Steve Biko ngalezo zikhathi e-Alan Taylor Residence. Konke kwaqala ukwenza umqondo! UDubazana uyena umuntu owaqala lamanga okuthi ngangiyimpimpi. Ngiyamkhumbula ekhona ngenkathi kuhlaselwa lendoda eyayisolwa ngokuba impimpi. Ukuqiniseka kwalomuzwa ngalokhu kukhumbula kusuka ekutheni ngikhumbula ubudlelwane enganginabo no Norman ngalezo zikhathi e-Alan Taylor. Lokhu ngikuhlanganisa nendlela ayebanda ngayo makuza ngakimina emva kokushawa kwendoda ngesitini endlili lomunye wamaqabane.

Lokhu kubanda kokuzwana phakathi kwethu kwangidida ngaleso sikhathi, ikakhulu kazi ngoba sasisondelene, sihlanganiswe ukuthanda kwethu i-martial arts kanye nokuzivocavoca, nesazama ukufaka kukho umngani osondelene wethu uBen Langa.

Ben was assassinated on 20 May 1984 by armed members of Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), the ANC’s military wing, after he was framed as being an informer. Ben’s younger brother Mandla Langa, also my close friend and comrade, recently sent me the following email:

UBen wabulawa ngomhlaka 20 May 1984 ngamalungu ayehlomile oMkhonto weSizwe (MK), umbutho wezempi we ANC, emva kokuba wabhecwa ngelokuba impimpi. Ubhuti omncane kaBen, uMandla Langa, ophinde abe umngani wami osondelele kanye neqabane, ungithumelele le-email:

“Dear Eugene,

Thanks so much. I received and downloaded the letters and will read them once the clamour has subsided in the house where there are too many people who have dropped in. On 12 March we exhumed and reburied the remains of four members of my family – Baba, Mama, Ben and Thembi – from the KwaMashu cemetery in F Section, which has become inaccessible, crime-ridden and waterlogged, to Botha’s Hill. It’s been a bit of a journey and I was happy at last to commune with Ben’s remains as I had been in exile and unable to return for the burial in May 1984. The same with Ma. There were scores of people from the community, and friends, some of them still harbouring the bitterness over how our family was isolated after Ben had been tagged an informer. These days, many of those who boycotted the funeral are reaching out to us, the family, and we’re still processing that. When I think of that I always try to put myself in Ben’s shoes and come to the conclusion that, since he was a very forgiving and generous person, materially and spiritually, he would have found it possible to let bygones be bygones if, say, any one of his brothers had been killed under those circumstances. I also think of the loneliness of Bhut Pius, who had to attend meetings where the men who had been hanged for killing his brother were praised to high heaven in the form of song.

Eugene Othandekayo,

Ngiyabonga kakhulu. Ngizitholile futhi ngazithwebula izincwadi kanti ngizozifunda uma sekunciphe ukuphithizela endlini lapho kunabantu abaningi abafikayo. Ngomhlaka 12 March simbile sakhipha imizimba yabane bomndeni wami – uBaba, uMama, uBen noThembi – ebebeKwaMashu F Section, nokuyindawo engasangeneki, inobugebengu kanye nokuba phakathi namanzi, sabayisa eBothas Hill. Sekube uhambo khona bengithokozile ekugcineni ukuba nomzimba ka Ben ngoba ngangisekudingisweni angikwazanga ukuza emngcwabeni ngo May 1984. Kuyefana naku Ma. Bekunezinkumbi zabantu basemphakathini, kanye nabangani, abanye babo besenokudangala ngendlela umndeni wethu wakhishwa ngayo inyumbazane emva kokuba uBen wabhecwa ngelokuba impimpi. Kulezi zinsuku, abaningi balabo abangezanga emncwabeni sebeyasithinta, umndeni, kanti sisabhekene nalokho. Mangicabanga ngalokhu ngiyaye ngizame ukuzifaka ezicathulweni zikaBen ngigcine nokuphuma nelithi, ngoba wayewumuntu onoxolo futhi enomusa, ngokwenyama nokomoya, wayezokwazi ukudlulisa axole, asithi nje, uma omunye wabafowabo ebengashona phansi kwalezo zimo. Ngicabanga futhi ngomzwangedwa kaBhuti Pius, okwakumele ahambe imihlangano lapho amadoda alengiselwa ukubulala umfowabo ayedunyiswa phezulu emazulwini kusetshenziswa ingoma.

Meanwhile, stay stone cool as you’ve always been. We’ll chat in time.

Okwamanje, hlala uphole okwetshe njengoba uhlezi unjalo. Sizokhuluma emva kwesikhathi.

And thanks again.

Ngiyazibongela futhi.

Mandla”

And so on that September morning when Abbey Cindi shoved open the rickety door to my outside bedroom to confirm my dream of Steve Biko’s transcendence, my tears spouted from the fountain of love’s everlasting flow…I wept like a baby and was filled with the profoundest sadness because I knew that I would not be able to attend the funeral of one of the greatest inspirations of my life. I succumbed to the fear for my own mortality when my courage was challenged. I failed to join the throngs of people in the historic moment of collectively memorialising the soul of one of our country’s greatest leaders who made the ultimate sacrifice by giving his life selflessly to our struggle.

Kuyenzekake ukuthi ngalelo langa ekuseni ngenkathi u-Abbey Cindi ephusha kuvuleka umnyango wangaphandle egumbini lami ukuzoqinisekisa iphupho lami lokudlula kuka Steve Biko, izinyembezi zami zaphuma kumthombo wothando ophuphuma ungashi…Ngakhalisa okwengane futhi ngigcwele ukudumala okunzulu ngenxa yokuthi ngangazi ukuthi angeke ngikwazi ukuya emngcwabeni womunye wabantu abangihola kakhulu ngomoya empilweni yami. Nganqotshwa ukwesabela impilo yami ngenkathi isibindi sami sicelwa inselele.

Ngehluleka ukuhlanganyela nezinkumbi zabantu ngalolusuku lomlando lokuhlangana sikhumbule umphefumulo womunye wabaholi balelizwe owazinikela wanikela impilo yakhe ngokungananazi kumzabalazo.

isiZulu translation by Mkhulu Maphikisa.

| 1. | ↑ | The renowned South African flautist and co-founder – with guitarist Philip Tabane – of the seminal group Malombo Jazzmen.Usaziwayo ongumdlali we-flute kanye nongomunye wabasunguli – kanye nomshayi wesigingci uPhilip Tabane – weqembu i-Malombo Jazzmen, |

| 2. | ↑ | In February 1973 I had been at the wheel of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) VW Kombi, with Biko in the passenger’s seat next to me, when we were escorted by the Security Branch to that same building, which served as their Eastern Cape headquarters, for the principal anti-apartheid activist of the time to be handed his five-year banning order. NgoFebruwari 1973 ngangishayela imoto ye South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) okuyi VW Kombi, uBiko wayehleli esihlalweni sabagibeli eceleni kwami, masesilandelwa iSecurity Branch sibheke kulelobhilidi, nelalisebenza njengekomkhulu lase Eastern Cape, ukuze lomgqugquzeli wezepolitiki olwisana nobandlululo ezothola incwadi yeminyaka emihlanu i-banning order. |