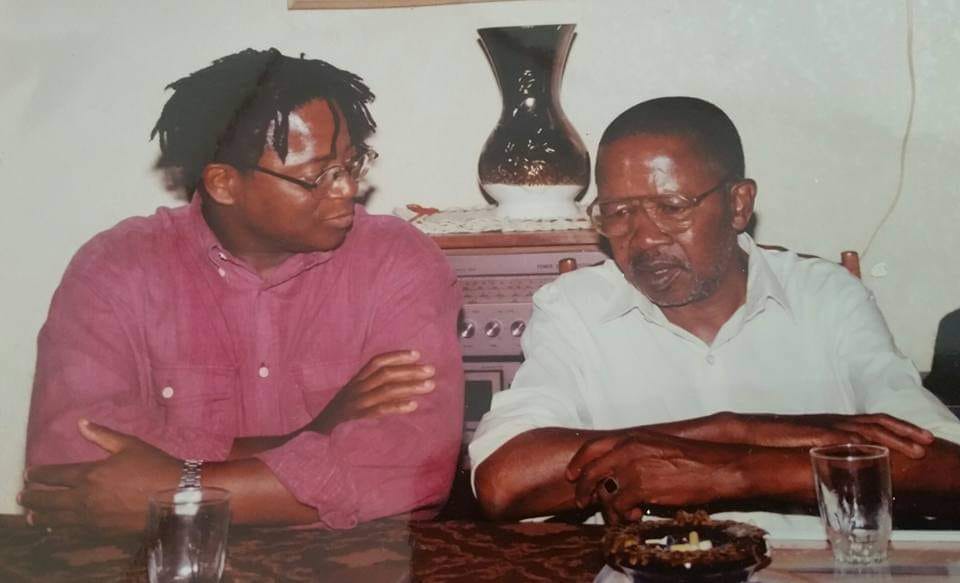

SANDILE MEMELA

Things My Father Taught Me

– there are more questions than answers –

My father was a messenger and registrar at an American research company, A. C. Nielsen, in Bree Street, Johannesburg. He walked the pavement to the central office in the CBD to collect or deliver letters and parcels. It was very important mail that carried survey results and other documents that told the story of market developments in society. Sometimes they measured the political mood.

I told friends that he was a clerk at work. He wore a white shirt and a jacket to the office. This made him look respectable.

He came to Johannesburg when he was 17 to start work in the mines. I don’t know how he ended up in high rise offices of Jozi. But he could read and write and spoke Shakespearean English, imitating a British accent sometimes. I learned that English was a powerful tool and instrument. If you spoke it well, you stood a chance in life. You could be mistaken for a highly educated or intelligent person. I think that is largely true.

My father had his standard 6, perhaps. I am not sure. As mentioned, he started work at 17 and was forced into early retirement at 60. He was devastated. He was a chain smoker and his lungs had almost collapsed. He had emphysema, a disease that smoked out your lungs. I don’t smoke.

For almost 30 years, I recall, he left the house around 6.30am or earlier. It did not matter whether there was Azikhwelwa or student upheavals in the township, he braved it to go to work. He was politically conscious but not an activist. I remember him saying as he quoted Shakespeare, “Politics is a game for knaves.” What are knaves, I asked. He advised me to learn to consult a dictionary. “Thugs,” he muttered.

In fact, he did not care for the much vaunted struggle. He believed that freedom or ‘one man one vote’ will not deliver equality and justice for the oppressed. He said every man had to work for himself. Fix the individual man, you fix the family. When a man fixes the family, he fixes the community. A happy man. A happy couple. A happy family. A happy community. Ultimately, a happy people. Thus a happy nation will be born.

I don’t remember a single day when he did not go to work because he had flu or a hangover. I guess he was a strong and healthy man who hid his pain and trauma. He was focused, disciplined and hard working in volunteered slavery.

He could not afford a decent life. We had to make do with whatever we had. I have always thought my father, this man who always came back home with a copy of The World newspaper, was the smartest man I knew. He would playfully hit me with the paper on the head and throw it on the table. He would look at me and say, “Read.”

“Dont forget to look up at least one word,” he would say.

When I was 7 years old, they called me Teacher Nhloko, the principal. I was regarded as a smart child because I read a newspaper at a young age. It was a compliment that boosted my confidence. And thus, because my father read the paper everyday, so did I. And we grew close to each other through this intellectual exercise. The written word is what bonded us.

I have no recollections of my father lifting me up or giving me a hug. I don’t remember when he kissed me or told me he loved me. He was a Zulu man who happened to live in the townships. He did not know how to express his feelings.

But he loved his family. He loved me, too.

When he was forced into early retirement because of his disease, he was not prepared. I don’t think he had any savings. They may have paid him for 3 months or so and let him go. Volunteered slavery, it was.

You get paid enough to come to the office. One day he came back home with a new watch. It was given to him for long loyal service. He had been with the company for 20 years. And all he got was a watch. Eish, these Americans. They have modernized slavery to a voluntary exercise.

So, when he was not working, we spent a lot of time together. We would be reading and talking and debating and asking questions. Sometimes, I would buy him his favorite Gordons. But I was not allowed to drink with him. He set clear boundaries.

It was these intellectual exchanges I loved most. I learned to examine and question every assumption. He encouraged me to do that: ask questions.

And he would be drinking his dry gin. And he would be on a roll, talking a lot of truth mixed with wisdom. The truth smelt like dry gin.

You have to give credit to men like him. He was self-taught; an organic intellectual if you like. They knew so much yet they did not hold a Masters degree or PhD. They just knew. I guess they possessed the quality of comprehension. You need to understand what’s going on in order to break it down.

In retrospect, I am not sure if I enjoyed it when he, playfully, hit me, again, on the head with his knuckles. He did that often when he asked me hard questions I could not answer. I was young and he would ask me, of all people: “Who is God? Why do you pray to Him when I am here? I am his image,” he would declare.

“What is Oliver Tambo doing in London? Why did Nelson Mandela go jail, abandoning his law practice? Why is Africa in such a mess? Above all, Who are You? And why are you on earth? Do you have a purpose?”

He did not demand or expect the answers from me. He was teaching me a lesson: ask questions. Question everything.

I think questions are more important than answers. My father taught me that it is very important for me or any man to think for himself. It is only a man who thinks that can ask questions, right questions that cut through the BS, like Socrates did.

The mind is everything. And one of the ways to put it to good use is to ask questions.

I truly enjoyed my intellectual musing with my father. He was the first man to shape me to be who I am. I wake up with love for him in my heart on some mornings. This piece is in his memory. Sometimes I miss my father. But I know he is not dead. I am his son. And his spirit lives in me.