PATRICIA PISTERS

Set and Setting of the Brain on Hallucinogen: Psychedelic Revival in the Acid Western

Abstract

This article investigates the current psychedelic revival in the set and settings of film culture. The so-called acid westerns of the rebellious youth culture of the early 1970s will be compared to contemporary revisions of the genre in light of more indigenous and diverse perspectives on psychedelics in our current epoch. Exemplary case studies are El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970), The Last Movie (Dennis Hopper, 1972), Blueberry (Jan Kounen, 2004) and Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles, 2019). By zooming in on these films, the argument is not to claim any direct causal relationship between these films and reality. Rather, the point is to demonstrate how cinema as an ideographic popular art form is part and parcel of a larger cultural set and setting around psychedelics and that the transformations in these particular trip films unfold new “worldings of the brain” in the context of the current psychedelic renaissance.

Keywords

neuropsychedelia, acid western, mind bending, counter-culture, shamanism, healing, change

Introduction: The Psychedelic Renaissance

Hallucinogenic and other brain stimulants have been part of human culture for ages. Varying from the use of peyote in Native American tribes to psilocybin in Mexican curandera practices and ayahuasca in Amazonian rituals, hallucinogens in indigenous cultures are deeply rooted and integrated in practices of wisdom and healing. (Davis; Adelaars et al.) European cultures, however, have labeled altered states of consciousness and alternative knowledge systems related to plant medicine and practices that are not aligned with patriarchal laws of State and Church as work of the devil, as phenomena that must be eradicated, as in the case of witch hunts (Papasyrou et al.). The secret and sacred traditions of altering consciousness met again in psychedelic research and culture of the 1960s, when psychedelics were used in clinical experiments as well as in counter-cultural settings. In the USA and other western cultures, Nixon’s War on Drugs declaration in 1971 put an end to many of these practices in the ensuing decades, when scientific use of mind manifesting drugs was banned and went underground in subcultural circles (Greer) and was partially continued in the rave culture of the 1980s and 1990s, though XTC and MDMA are considered “empathogens” rather than hallucinogens (Shulgin). In Latin America and among indigenous cultures in other parts of the world there was no such radical rupture in the legal and cultural status of hallucinogens.[1]In Peru, for instance, ayahuasca officially belongs to the national heritage. One also has to note here that the Spanish conquistadors did eliminate many indigenous cultures and shamanic practices in the colonialization of the Americas.

Recent suggestions of a psychedelic renaissance refer to the revival of hallucinogen research in the West that picked up again in the 1990s and which has evolved rapidly during the last two decades. In Neuropsychedelia (2013) Nicholas Langlitz maps out how this research has progressed in the decade of the brain, while Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind (2018) situates the popularization of the psychedelic revival in a broader cultural context. Langlitz focuses on the rise of neuropsychopharmacology as a field of research centered on neuroscientific and psychiatric clinical studies on the therapeutic effects of ketamine, MDMA, psilocybin and LSD to treat depression, post-traumatic stress and other mental conditions, a development that is slowly but surely changing the field of psychiatry (Tullis). However, contrary to symptom-suppressing medications such as anti-depressants and anti-psychotics, the use of psychedelics raises philosophical and religious questions about the human soul and its relation to nature, the world and the cosmos. Because of their healing, spiritual and entheogenic potential that open new “doors of perception” (Huxley), psychedelics demand a more holistic and transdisciplinary approach that goes beyond the scope of the bio-medical sciences.[2]The other scientific fields that are strongly involved in the psychedelic renaissance are anthropology and ethnobotany. Adams et al., 2013; Luke and Spowers, 2018.

Moreover, as Eric Davis in High Weirdness argues, the extra-ordinary perceptions and experiences that come with psychedelics are “weirdly mediated a lot of the time,” often through myths, stories, images in popular culture and media technology (31). Hence, to gain a better understanding of the novel questions raised by the current psychedelic renaissance, it is vital to interrogate the past and present of the media forms and repertoires in and through which new psychedelic understandings emerge. In the following, I will examine emblematic and historically changing cinematic reflections on psychedelia through the lens of one specific popular film genre, the so-called “acid western”. The choice of this subgenre is pragmatic, in the sense that its relation to psychedelics and its peculiar manifestations is explicit, even if sometimes only generic.[3]The term “acid” refers to LSD, but in as a genre reference it is often taken as a more generic term, taking LSD as prototypical psychedelic, even if other psychotropics are often referred to the films that are designated by this term, especially in its transformations after the 1970s. Many other relations between film and drugs can be made (James), but these are beyond the scope of this article. By considering acid westerns as a type of fictional trip reports that resonate with broader developments in society, I will ask how this genre helps to trace a “worlding of the brain on hallucinogens” that is indicative of the psychedelic renaissance.[4] See Doyle 2013 for an extensive study on the value of trip reports as scientific method. By “worlding of the brain” I refer to the scope of this volume to stage an encounter between bio-medical and cognitive science of the brain and social and cultural disciplines.

Collective Set and Setting of the Hippie Exploitation Film and the Acid Western

After Timothy Leary introduced the concepts of set and setting in psychedelic experiments, they have become an integral part of psychedelic practices and discourse. Set, or mind set, refers to personality, expectation, and intention of the person taking a psychedelic substance. Setting indicates the social, physical, and cultural environment in which the experience takes place. In his book American Trip Ido Hartoghsohn has proposed that set and setting are not only important for individual experiences, but also have an important collective dimension. Across several large sets and settings (such as the experimental psychosis movement in psychiatry or experiments by the CIA and Sillicon Valley psychedelic innovation workshops), Hartoghsohn demonstrates that the effects of psychedelics are “predominantly the result of sociocultural tendencies and interpretations”(12). Hartogsohn argues, for example, that the notorious bad trip became more prominent as an experience “after the media started to report more on this phenomena and societal and political consensus moved towards the war on drugs” (206). Hence, psychedelic experience are shaped by multiple feedback loops between psychedelic substances and (mediated) cultural repertoires in society.

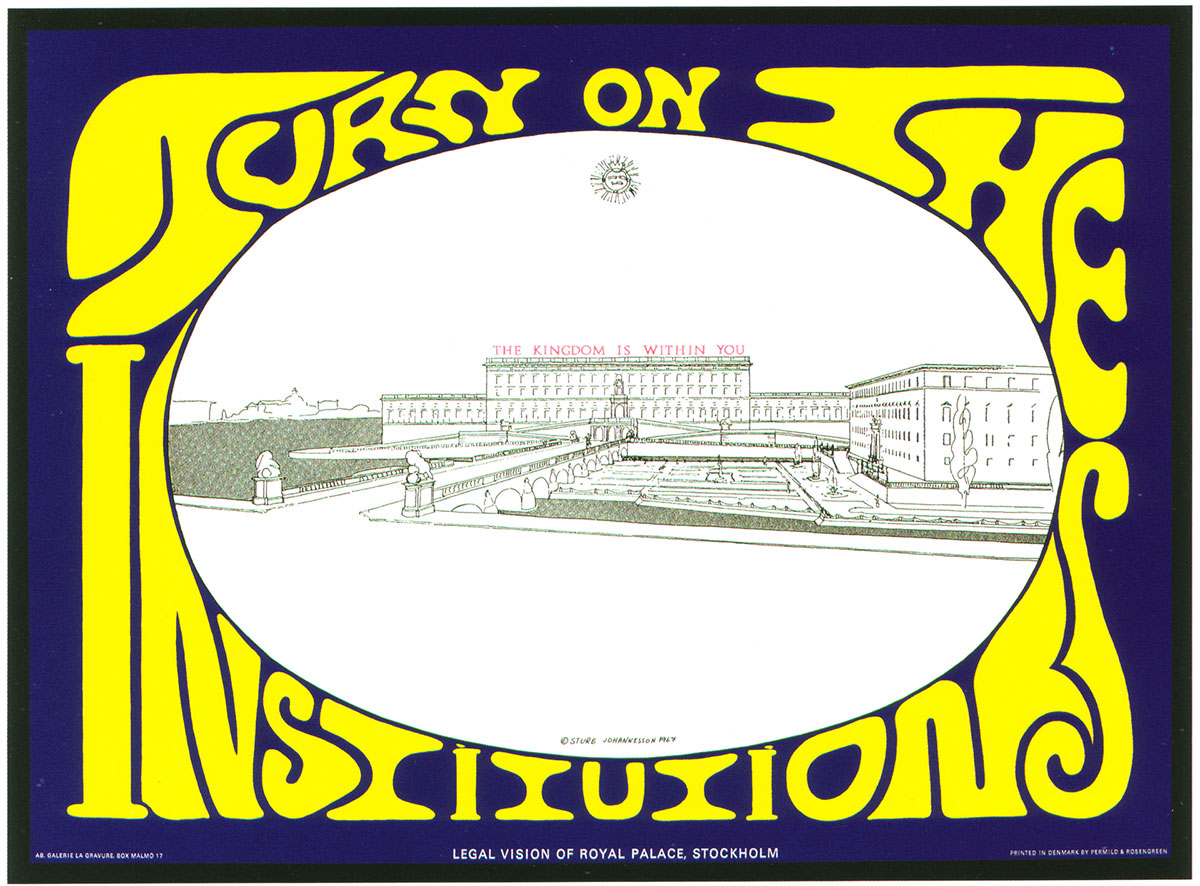

The creative and artistic field of the 1960s is the pre-eminent example of the close entanglement of psychedelic manifestations with their societal and collective set and setting (Hartogsohn; Davis; Das and Metzner). As a cultural style we are all familiar with the cliché curly letters and patterns on psychedelic posters, the flower power hippie-look and the typical dreamy or acid music styles, ranging from the Beatles to Jefferson Airplane and Jimmy Hendrix. Moreover, the 1960s saw experiments with artistic creativity by administrating LSD to painters, writers, musicians, actors and filmmakers (Hartogsohn 131); many artists self- experimented with psychedelics, as did tech-innovators in Silicon Valley (Markoff, Turner 2006). As one organizer of a psychedelic training workshop explained: “We said, for instance, you can try to identify with the problem from other vantage points than you’d usually use. You can see the solution. Visualize the part. Go inside the various parts of the physical apparatus. (…) You can see it in fresh perspectives” (Hartogsohn 157). LSD, mescaline or psilocybin were not seen as an easy fix for problems of creativity but certainly as potential mental boosters. As creative catalysts, psychedelics generated varying stylistic repertoires in different cultural contexts. Hartogsohn mentions the difference, for instance, between the rowdy acid tests of the West Coast’s sunny beaches and the grittier New York variation of psychedelia, more related to speed and the artistic underground scene (142, Turner).

Cinema has played an important role in the popularization of ideas about psychedelia and forms its own collective set and setting. While trippy science fiction films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick 1968) and drug-infused road movies such as Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper 1969) were shaping and shaped by a particular Zeitgeist, many of the controversies around psychedelics also found their way in the B-genre of the so-called hippie exploitation film. After the CIA’s loss of interest in LSD as potential mind control weapon, the rising scandals around the figure of Timothy Leary, and the association of drugs with anti-government protests and rebellion during the Vietnam war, the discourse on these mind expanders got marked by larger societal narratives of disapprobation. Michael DeAngelis cites an 1963 article in the Saturday Evening Post entitled “The Dangerous Magic of LSD” as exemplary for the way in which a general fear for LSD was provoked, associated with pathology and mind control (130).

The portrayal of psychedelics in films such as Hallucination Generation (Edward Mann, 1966), Riot on Sunset Strip (Arthur Dreyfus, 1967), The Love-Ins (Arthur Dreyfus, 1967) and Psych-out (Richard Russ, 1968), catered to a young generation, yet eventually subscribed to the cultural consensus of the older generation that tripping is bad, and thus by and large followed the general consensus of the dominant set and setting of the War on Drugs.[5]While the “hippie” is considered an American invention, it is a transnational phenomenon. European hippie trash” or cult films include, for instance A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (Lucio Fulci, 1971) and Performance (Nicholas Roeg, 1970). See also the documentary Soviet Hippies (Terje Toomistu, 2017). Only a few films, such as The Trip (Roger Corman, 1967) and Skidoo (Otto Preminger, 1968) give more nuanced perspectives on the potential dangers but also therapeutic benefits and entheogenic or spiritual insights of psychedelics. The Trip was praised for its authentic depiction of the experiences of its tripping protagonist Paul (Peter Fonda) who at one point exclaims that an orange is like holding the sun in his hands, and that he can see right through his own brain. Paul also confronts his marriage problems, emphasizing the therapeutic value of his psychedelic journey (DeAngelis, 139-140). Hence, these 1960s films can be considered time capsules that embody the generational conflict over psychedelics.

The acid western is a subgenre within the domain of countercultural hippie films that appropriates the repertoire of the Western to translate the psychedelic mindset by stretching the rules of the genre. The western is pre-eminently bound up with the emergence and development of Hollywood film culture itself. André Bazin called the western “cinema par excellence” (141). Defined by its setting in the frontier towns and vast landscapes of the American West, and by the iconic figure of the cowboy as the image of heroic masculinity, the genre is (not unproblematically) associated with mythological adventure and conquest.

John Ford’s Stage Coach (1939) is often cited as the prototypical western, in Bazin’s words, a “maturity of a style brought to classic perfection” (149). The genre has been revised both from within Hollywood (the revisionist Westerns of Arthur Penn, for instance, create more space for Native American perspectives, albeit still mediated by a white male protagonist) and from outside Hollywood, as in the famous spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone that present a more cynical view on the violence and monetary motives of its heroes.

The aura of absolute freedom associated with the cowboy, and even the cowboy aesthetics nevertheless also resonated with the countercultural generation. A case in point is Dennis Hopper’s hippie cowboy looks and the transformation of the western image of freedom into the road movie in his film Easy Rider. The acid western resonates with the psychedelic rebellious counter cultural spirits of the time, when psychedelics were already on the list of forbidden substances, the bad trip had gained prominence and when the ideals of freedom and flower power had moved into more vehement political protests and demonstrations against the Vietnam war and for sexual liberation and racial equality. In a way, the acid western can thus be understood as a stylistic protest genre against the established rules. It designates a subgenre of the western that puts genre conventions completely upside down in combining the masculine violence of the classic western with the absurd to “conjure up a crazed version of auto-destructive white America.” (Rosenbaum; Taylor). Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970) and Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie (1971) were released around the same time and point to different aspects of the connections between psychedelics and cinema in the rebellious spirit of the late 1960s and early 1970s.[6]El Topo was the first film marked as acid western. Later other (also earlier) films have been added, such as The Shooting (Monte Helmann, 1966), Zachariah (George Englund, 1971), Greaser’s Palace (Robert Downey Sr., 1972). Also Walker (Alex Cox, 1987) and Deadman (Jim Jarmush, 1995) have been labelled acid westerns.

The term “acid western” was coined by film critic Pauline Kael after the release of El Topo in 1971, describing how the film turned into an instant cult phenomenon that was shown for months in packed midnight theaters in New York (Rosenbaum; Mikulec). Kael’s term actually referred to the doped midnight audience that was watching Jodorowsky’s film and not to the film itself. Nevertheless El Topo came to designate certain transformations of the western genre associated with the acid aesthetics of the counterculture. Working outside Hollywood, and shot in Mexico on an extremely low budget, Jodorowsky transformed the exploitation genre in his own idiosyncratic way by creating images that “create a mental change” in a film that “is LSD without LSD” (Jodorowsky in Ivan-Zadey).

Jodorowsky himself plays El Topo, the black leathered cowboy who goes on a bizarre symbolic and spiritual quest in the desert which, halfway in the film, leads to his rebirth in a cave where he helps to escape the wretched of the nearby town by digging a tunnel. There is plenty of blood, sex and violence in the mise-en-scene, but in the end one realizes this is all part of a process of soul searching that involves both virtues and vices. By putting all genre rules upside down, remixing with incredible affective intensity the collective ideas and images about masculinity and femininity, violence and sexuality, we understand that Jodorowsky is a mind bending artist who bypasses the collective norms of the time by creating his own set and setting that therefore gains perennial qualities. El Topo undermines genre conventions by brewing all its elements in a surreal and alchemical transformation, which creates a psychedelic experience without any drug. The images themselves are colorful, extreme and hallucinatory, disturbing and insightful at the same time. And as such El Topo translates something of both the insubordinate spirit as well as the weirdness of the collective psychedelic set and setting of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Blowing Up Hollywood: The Last Movie Hallucinatory Sexism and Racism

While Jodorowsky came to the film industry as an outsider and used the western genre as an entrance point to create his own peculiar psychedelic universe, Dennis Hopper was an insider of Hollywood who unraveled genre conventions from within the system. The Last Movie feels like a feverish bad trip. However, unlike other hippie exploitation films, this is not a film about drugs, but rather a film made on drugs. Much of the chaos and of the sex, drugs and alcohol that we see consumed in front of the camera reflects the crew’s behavior on and off set (Chinchero was famous for its cocaine production at the time). The psychedelic nature of the film is conveyed by the unruly, jagged editing, and in the wildly looping self-reflexive and hyperbolic style of the mise-en-scene (Kohn, Ayd).

Hopper himself plays the lead in The Last Movie, similar to Jodorowsky’s appearance in El Topo. Hopper is Kansas, a disillusioned and depressed stuntman of a Hollywood western that was shot in the Peruvian Andes mountains. Kansas stays in the Peruvian village after the production is wrapped and hooks up with a local prostitute Maria (Stella Garcia). The villagers use the décor of the film for reenacting their own version of the script, using film equipment made out of wooden sticks and replacing fake violence for real violence. On this meta-level The Last Movie seamlessly mixes the actual shooting conditions, the Hollywood western and the version of the western shot by the locals to question the role of cinema. By demonstrating how real violence and actual violence bleed into one another, The Last Movie questions the influence of Hollywood tropes and stereotypes. The few scenes in ‘the film in the film’ that is produced by the Hollywood crew consists only of shoot outs and extreme violence: everybody shoots everybody, laying bare the deeply rooted violence of the conquest of the West. This violence in and of (Hollywood) filmmaking is shown to the point of troubling absurdity in the mise-en-scene of guns and falling and bleeding bodies. Moreover, by dismantling the entire grammar of the plot by presenting the events in non- chronological order (even the titles of the film appear at several places throughout the film), The Last Movie explicitly shows the distressing building blocks of sexism and colonialism.

So on this very concrete level of the mise-en-scene and editing of the film, The Last Movie both confirms and destroys the myths of the western and thus translates the revolutionary protest spirits of the counterculture. As a masculine genre, the western actually exemplifies the entire Hollywood industry and a society dominated by the white male gaze, much criticized by the emancipation movements of the 1970s. By calling his film The Last Movie Hopper shows the destructive extremes of dominant (Hollywood) culture, while also participating in it. The depiction of women as worthless products is painful to watch. Even if one scene shows how Kansas himself is hit by a woman, this does not make up for the evident sexism and violence against women. Moreover, the colonial gesture of the invasion of a western film crew in the Peruvian village Chinchero cannot be ignored either.

The fact that the indigenous natives re-enact the movie-making ritual reinforces the notion that Hollywood also colonizes peoples’ mental spaces with these violent ideas.

The film can certainly be seen as subscribing to all these problematic dimensions of the western. And yet, at the same time, because of all its subversive elements in style and production, the message of The Last Movie feverishly announces the end of an era by dismantling the Hollywood film industry and its inherent power structures.

Where the violence in El Topo is surreal and symbolic and part of a trajectory of spiritual death and rebirth, as encounters with good and bad in order to learn and change, the violence in The Last Movie is allegorical, exposing the western (and Hollywood more largely) as part of Western patriarchal colonialism that is based on the desire for conquest.

Because of this, both films are at times difficult to watch, and yet, since these are quite remarkable acid westerns that refract each in their own way the conventions of filmmaking and open new perspectives, these films remain unique sign posts in cinema that mark the end of the countercultural era where the collective set and setting of psychedelics was coloured by the disillusion of the flower power movement and its insistent association with the bad trip. In the meantime the war on drugs and the ban on psychedelia had stopped most clinical studies on the use of psychedelia. Culturally the “hippie scenes” everywhere in the world were replaced by other subcultures and youth scenes, including the ravers of the 1980s and 1990s when XTC took over from the classic psychedelics of the 1960s counterculture. More recently, with the emergence of a new psychedelic renaissance since the 2000s, there has been a remarkable return to the tradition of the acid western. Tracing the similarities and difference between these recent examples and the acid westerns of the psychedelic revolution in the 1970s helps to understand the shifting but persistent critical potential of genre subversion.

Blueberry’s Ayahuasca Gold Rush and the “Western” Quest for Shamanic Healing

Since the 2000s, a growing number of clinical and neuroscientific experiments in the therapeutic properties of psychedelia are prudently set up. Such experiments need to be carefully monitored and mediated to gradually counter the longstanding controversial imago of psychedelics (Langlitz; Calvey; Pollan) Recent documentaries such as Trip of Compassion (Gil Karni 2017) and From Shock to Awe (Luc Coté, 2018) show the experiences of several patients with severe symptoms of trauma when they receive treatment with MDMA or ayahuasca. They present deeply moving insights in the remarkable effects these drugs have on patients, and the different approach they demand from doctors, psychiatrists or shamans who guide the patients in their journey toward healing. In these and other popular media productions, such as the Netflix feature Have a Good Trip (Donic Cary, 2020), there is a noticeable shift in the way drugs culture is portrayed that resonates with larger societal changes towards the brain on hallucinogen. Additionally, in fiction film there is also renewed attention for narratives about the use of hallucinogenic substances and the integration of an immersive psychedelic style. Contemporary versions of the “acid western” reveal a number of updates to the genre. One striking revision is that more explicitly than before, the typical American genre of the western has become a “global genre” (Costanzo, 204).[7]Jodorowsky and the Spaghetti western were mentioned before. The Wuxia, Samurai, and Kung Fu films in China, Japan and Hong Kong have influenced and been influenced by the Western. The Good, the Bad and the Weird (Kim Jee-Woon, 2008) is a Korean translation of the Spagetthi western. Two contemporary acid westerns provide particularly salient expressions of the new cultural dimensions of the contemporary psychedelic revival: Jan Kounen’s ayahuasca western Blueberry (2004) and Kleber Mendonça Filo & Juliano Dornelles psychotropic western Bacurau (2019).

Kounen’s Blueberry can be considered a film that previsions the current psychedelic revival, which is commonly marked by a large 2006 symposium on LSD in Basel, organized on the occasion of the hundredth birthday of Albert Hofmann, the inventor of LSD. Blueberry is loosely inspired by the Moebius comics of Jean Giraud (started in the 1960s) and presents the story of Mike Blueberry (Vincent Cassel), nicknamed Broken Nose. The film is shot in the Mexican desert, featuring typical Western elements such as cowboys, saloons, greedy gold rushers and Native Americans. However, contrary to the previous recalcitrant acid westerns, in Blueberry the Amazonian ayahuasca rituals feature as the film’s “mind set” based on Kounen’s experiences with these sacred ceremonies during his frequent visits to Peru in the 1990s. In his 2015 book Visionary Ayahuasca, Kounen presents the notes of his inner journeys to meet healers and to undergo “a few hundred ceremonies” that he practices with the Indigenous Shipibo people (Kounen). He is therefore dubbed a “cineaste ayahuasquero,” a filmmaker who embraces ayahuasca (1). The journey notes are composed as a “metaphysical drama, constructed in flashback mode,” in which Kounen himself is the hero, much like his hero in Blueberry. (4).

Looking at Blueberry in relation to the 1970s acid westerns of Jodorowsky and Hopper, it is striking to see that the iconography and the grammar of the western remains more intact compared to the crazy and intense transformative symbolism of El Topo and the wild achronological self-reflexive and self-destructive structure of The Last Movie. Blueberry stays closer to the traditional storyline of the genre: a stranger arrives in a typical western town, enters into a conflict and after several duals and shoot outs, there is a resolution of the conflict. However, in Blueberry the sought after gold is not the precious stone of the traditional goldrush but the secret and holy ayahuasca brew that creates deep insights and is the source of healing. Ayahuasca, as spiritual gold, has been integrated into the narrative where Blueberry confronts the villain Blount (Michael Madsen) inside the Sacred Mountain where they challenge each other in a trip. In this sense, it is possible to read Blueberry as a visionary allegory of the current psychedelic revival, which sometimes is indicated as the psychedelic goldrush, referring to the countless capital ventures and startups who have discovered psychedelics as a new “gold mine” (Farah). Obviously, the development of entrepreneurship and patents is not without risks of appropriating and stealing from indigenous communities who are not included in these ventures (Gerber et. al. 2021).

At the same time, Blueberry also reflects another dimension of the psychedelic revival. Rather than countercultural rebellion, the European and North American cinematic manifestations of the psychedelic renaissance are more directed towards healing. Kounen’s western is a healing journey in which Blueberry confronts his traumatic memories with the help of the spiritual guidance of his Native American friend Runi (Temuera Morrison) whose family took care of Blueberry after he was found wounded. While the theme of a white man growing up with native Americans is not new (in fact it is a central fantasy in revisionist westerns such as Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man (1970) and Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) ) the emphasis on traumatic memories and healing via plant medicine is clearly a new dimension that is part of the current psychedelic revival, previsioned by Blueberry. In the film, the ayahuasca visions are represented in splendidly immersive images, full of graphic details in golden mandalas, bird’s eyes perspective in flight, and (scary) confrontations with totemic and archetypical animals that guide him to see the painful and repressed truth of his memories. (Recently, Kounen has reinvigorated these immersive qualities in a VR-experience titled Ayahuasca Kosmik Journey (2019) ). Only when Blueberry confronts his own inner demons, he can fight his opponent. Rather than subversively undermining the genres of the western, Kounen opens up the genre to inner visions and spiritual growth. It could thus be argued, Blueberry is exemplary for the psychedelic renaissance: instead of resonating with a rebellious counter-culture the film rather reflects the spirit of integration into existing practices.

As in other westerns, the role of women has not changed much (it’s the favorite prostitute of both Blueberry and Blount who is the direct cause of their conflict; and since she dies, she is also the source of Blueberry’s trauma). In regard to gender, the rules of the genre basically remain the same. In turn, the colonialism that is part of The Last Movie in its invasion of Peru as set and setting of the excessive drugs consumption of cast and crew, has now been replaced by the implicit references to westerners looking for spiritual healing via the plant wisdom of the Amazon. As Kounen indicates in his book, since he started traveling to Peru in the 1990s, spiritual tourism grew exponentially, which prompted him to write a manual included in Visionary Ayahuasca (143-250). In the film, as in reality, the Native Americans hold the wisdom to this ancient knowledge, decimated in the conquering of the West. By including these deep insights into knowledge of the soul, Blueberry points towards the growing importance of ayahuasca in the psychedelic revival as important healer for PTS and other traumas (Adelaars et al.). As indicated before, there is a danger this may lead to neo-colonial practices of a new “gold rush,” or simply to renegade tourism that does not respect the rules and ritual. Such dangers need to be addressed critically (Williams and Labate). Yet, we can sense here that within the confinements of Western culture, self-criticism, modesty, respect and a desire for transcultural and transhuman (plant) knowledge is opening up. In this sense, Blueberry constitutes a different type of “acid western” as “aya western”, a novel variation of the genre that resonates with larger developments in the world marked by the psychedelic renaissance.

Shooting Back and Collective Action in Psychotropic Western Bacurau

While most variations of the acid western have white, male and heterosexual characters in the lead (even though their position is also undermined in and sometimes literally shot to pieces), the film Bacurau, as the latest addition to the acid western subgenre tree, brings to the fore an important new perspective. Not only is the US setting of the frontier town transposed to Brazil, but importantly, the film is told from the perspective of minorities that have not been central to the western: indigenous people, the colonized, refugees, black populations, women and non-binary gendered characters (see also Zang). They are the central characters in Bacurau and in this film the western is appropriated to express resistance and self-esteem.

Bacurau is a remote and isolated town in the hinterlands, the sertão (the “wild west”) of Brazil, where the action takes place. A resident, Teresa (Bárbara Colen), returns to her hometown for the funeral of her mother when the town is attacked by a group of armed, drone-assisted foreigners looking for entertainment and opening the hunt (Bittencourt). But the residents hit back. Writers and directors Mendonça Filho and Dornelles use the conventional semantic elements of heroes and villains (Altman), but they turn all the iconic archetypes of the western upside down: not one brave man, but an entire village becomes the collective hero of the film. The genre rules are stretched further by hallucinatory images. The village seems to have its own psychedelic means of fighting:

“we have taken a powerful psychotropic, you are going to die”

one of the villagers tells the villains in a final shootout scene. This non-specified psychedelic, and the entire revisionist story of the film, can be read as an allegory that offers an important political commentary.

As a political allegory the film operates on at least three levels of resistance. First of all, the corruption of Brazilian politics itself is addressed. The local politician Tony Jr. (Thardelli Lima) regularly arrives in town to buy votes by distributing cheap and outdated food and addictive painkillers while at the same time putting pressure on the village by cutting off water supplies and by allowing American tourists to come in for shooting games, thus silencing, quite literally, the villagers. The hypocrisy and corruptness of the politician is explicitly revenged by the united villagers at the end of the film. Secondly, another level of resistance marked by references to the western is directed towards the masculine figure of the cowboy. The gun crazy and ruthless “cowboys” that come in to hunt are tricked to enter the village museum that holds many western memorabilia, including old shot guns. By taking revenge on these structural elements of the Western shoot out, the villagers change the traditional rules of white masculinity: they call in the non-binary gendered local rebel Lunga (Silvero Pereira) to help out in the counter strike. Moreover, by completely bending the rules of the genre’s hero narrative, the film retaliates against the position of the western (and of Hollywood film more generally for that matter) in our collective unconscious. Thirdly, by referring explicitly to the devastating addictive effects of big pharma medication, expressed most explicitly by the town’s doctor Domingas (Sonia Braga), and the emphasis on the community’s own plant medication, the film references key themes of the psychedelic revival. The status of symptom-suppressing, conventional medicines versus the more profound healing properties of psychedelics are an important part of current debates.

Bacurau addresses a vital aspect of the psychedelic renaissance that has not yet been mentioned: the necessity to change the balance of power in the world. While Blueberry shows the danger of Western “treasure hunters” of all sorts going to the Amazon only to get gold, Bacurau gives voice to those who have never been heard in the mythology of the western, and for whom the psychedelic renaissance is not a renaissance at all, but an ancient tradition. By way of these genre revisions, transformations and appropriations, Bacurau addresses the need for active resistance to old and engrained power structures that tend to return, as well as the importance of agency from the perspective of a range of diverse characters that have always been placed in minority positions. This aspect of the indigenous and ancient traditions and wisdom of the psychedelic revival currently receives increasing attention and Bacurau, as a “psychotropic western” makes a case in point in this respect.

The Weird and the Disturbing in the Psychedelic Revival

The genre of the acid western that emerged within the set and setting of the psychedelic counter-culture of the 1960s and early 1970s offers “weird mediations” and imaginative translations of the brain-on-psychedelics. Its transformations and adaptations in more recent times resonate more clearly with concerns of the current psychedelic revival. Taken together, these films offer, in their historical variation, a cultural prism that reflects larger cultural and political questions entangled with the past and present psychedelic movements. Jodorowsky’s surreal El Topo, with the midnight crowds it inspired, as well as Hopper’s The Last Movie, with an explosive and disillusioned force that marked the end of an era, are connected to the rebellious spirit of the counterculture. This type of rebellion has been replaced by the integrative qualities of Blueberry, which returns to the classic language of the western, but transforms into a quest for healing and plant wisdom that is prevalent in the current psychedelic renaissance. And the resistance of Bacurau, as a hybrid psychotropic western, addresses the power and agency of indigenous views and diverse minority perspectives to battle traditional power structures. This new generation of acid westerns also implicitly warn against neo-colonial practices that threaten to spur a new “psychedelic gold rush” in cultural and neuropharmacological medical practices today. In any case these films demonstrate that the confrontation with the weird, the disturbing, “the good, the bad and the ugly” are necessary for both individual and collective healing in the set and setting of the psychedelic renaissance.

Adams, Cameron, David Luke, Anna Waldstein, Ben Sessa and David King, eds. Breaking Convention: Essays on Psychedelic Consciousness. Strange Attractor Press, 2013.

Adelaars, Arno, Christiaan Ratsch and Claudia Muller-Ebeling. Ayahuasca. Rituals, Potions and Visionary Art from the Amazon. Divine Arts, 2006.

Altman, Rick. “A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre.” Cinema Journal, Spring 1984, 6-18.

Ayd, Jade and Jennifer Ayd. “The Last Movie: Dennis Hopper’s Curiously Frustrating Experiment.” Moving Image. 30 July 2019. Accessed 30 January 2021.

Bazin, André. “The Western: or the American Fil par excellence.” and “The Evolution of the Western”. What is Cinema? Volume II. Essays selected and translated by Hugh Grant. University of California Press, 1971, 140-157.

Bittencourt, Ela. “Rise Up! Interview with the Makers of Bacurau.” Film Comment. March- April 2020. Accessed 3 April 2021.

Calvey, Tanya, ed. Psychedelic Neuroscience. Special issue Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 242, 2018.

Costanzo, William. World Cinema Through Global Genres. Wiley & Blackwell, 2014.

Davis, Erik. High Weirdness. Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies. MIT Press, 2019.

Das, Ram and Ralph Metzner. Birth of a Psychedelic Culture. Synergetic Press, 2010.

DeAngelis, Michael. Rx Hollywood. Cinema and Therapy in the 1960s. State University of New York, 2018.

Doyle, Richard. Darwin’s Pharmacy: Sex, Plants, and the Evolution of the Noosphere. University of Washington Press, 2013.

Farah, Troy. “Psychedelic Gold Rush? Psilocybin Startup Compass Pathways Goes Public at More than $1B.” Double Blind 29 September 2020, Updated 12 March 2021.

Gerber, Konstantin, Inti García Flores, Angela Christina Ruiz, Ismail Ali, Natalie Lyla Ginsberg, and Eduardo E. Schenberg. “Ethical Concerns about Psilocybin Intellectual Property.” ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2021 4 (2), 573-577.

Greer, Christian. Angel-Headed Hipsters: Psychedelic Militancy in Nineteen-Eighties North America. PhD Dissertation. University of Amsterdam, 2020.

Hartogsohn, Ido. American Trip. Set, Setting, and the Psychedelic Experience in the Twentieth Century. The MIT Press, 2020.

Huxley, Aldous. The Doors of Perception. Chatto & Windus, 1954.

Ivan-Zadeh, Larushka. “El Topo, the Weirdest Western Ever Made.” BBC Culture, 23 July 2020. Accessed 29 January 2021

James, David. “The Movies Are the Revolution.” Imagine Nation. The American Counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. Edited by Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle. Routledge, 2002, 275-304.

Kohn, Eric. “The Last Movie: Dennis Hopper’s Misunderstood Masterpiece Deserves a Second Chance.” Indiewire. 2 August 2018. Accessed 30 January 2021.

Kounen, Jan. Visionary Ayahuasca. A Manual for Therapeutic and Spiritual Journeys. Park Street Press, 2015.

Langlitz, Nicholas. Neuropsychedelia. The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain. University of California Press, 2013.

Luke, David and Rory Spowers, eds. DMT Dialogues: Encounter with the Spirit Molecule. Park Street Press, 2018.

Markoff, John. What the Dormouse Said. How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. Penguin, 2006.

Masters, Robert and Jean Houston, eds. Psychedelic Art and Society. Grove Press, 1968. McLuhan, Marshall and Quentin Fiore. The Medium is the Massage. Penguin, 1967.

Mikulec, Sven. “A 1971 Interview with Jodorowsky on El Topo, the Psychedelic, Genre- Bending Midnight Movie.” Cinephilia & Beyond. Accessed 29 January 2021.

Papasyrou, Maria, Chiara Baldini and David Luke, eds. Psychedelic Mysteries of the Feminine. Creativity, Ecstasy, Healing. Park Street Press, 2019.

Pollan, Michael. How to Change Your Mind. The New Science of Psychedelics. Allen Lane, 2018.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. “Acid Western” Chicago Reader. 27 June 1996. Accessed 1 February 2021.

Shulgin, Alexander and Ann. Pikhal. A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press 1991.

Taylor, Rumsey. “Acid Westerns.” Not Coming to a Theater Near You. 1 April 2013. Accessed 1 February 2021.

Tullis, Paul. “How Ecstasy and Psilocybin are Shaking up Psychiatry.” Nature 27 January 2021, Accessed 30 January 2021.

Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Turner, Fred. The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism Form World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Williams, Monica and Beatriz Labate, eds. Special Issue on Diversity, Equity and Access in Psychedelic Medicine. Journal of Psychedelic Studies 4(1), 2020.

Zang, Pam. How Much of these Hills is Gold? Riverhead Books, 2020.

| 1. | ↑ | In Peru, for instance, ayahuasca officially belongs to the national heritage. One also has to note here that the Spanish conquistadors did eliminate many indigenous cultures and shamanic practices in the colonialization of the Americas. |

| 2. | ↑ | The other scientific fields that are strongly involved in the psychedelic renaissance are anthropology and ethnobotany. Adams et al., 2013; Luke and Spowers, 2018. |

| 3. | ↑ | The term “acid” refers to LSD, but in as a genre reference it is often taken as a more generic term, taking LSD as prototypical psychedelic, even if other psychotropics are often referred to the films that are designated by this term, especially in its transformations after the 1970s. |

| 4. | ↑ | See Doyle 2013 for an extensive study on the value of trip reports as scientific method. By “worlding of the brain” I refer to the scope of this volume to stage an encounter between bio-medical and cognitive science of the brain and social and cultural disciplines. |

| 5. | ↑ | While the “hippie” is considered an American invention, it is a transnational phenomenon. European hippie trash” or cult films include, for instance A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (Lucio Fulci, 1971) and Performance (Nicholas Roeg, 1970). See also the documentary Soviet Hippies (Terje Toomistu, 2017). |

| 6. | ↑ | El Topo was the first film marked as acid western. Later other (also earlier) films have been added, such as The Shooting (Monte Helmann, 1966), Zachariah (George Englund, 1971), Greaser’s Palace (Robert Downey Sr., 1972). Also Walker (Alex Cox, 1987) and Deadman (Jim Jarmush, 1995) have been labelled acid westerns. |

| 7. | ↑ | Jodorowsky and the Spaghetti western were mentioned before. The Wuxia, Samurai, and Kung Fu films in China, Japan and Hong Kong have influenced and been influenced by the Western. The Good, the Bad and the Weird (Kim Jee-Woon, 2008) is a Korean translation of the Spagetthi western. |