JOHNNY MBIZO DYANI, one of the most accomplished bassists to have come out of South Africa, died on stage at the Berlin Festival on Friday, 24th October 1986. He was born in East London on November 30, 1945[1]“We don’t know where exactly Johnny was born, although it was probably in the home of Ebenezer Mbizo Ngxongwana and his wife Nonkhatazo. We don’t know who were present, and even the date of the event has been under discussion. According to the Home Office in King William’s Town, Johnny was born on June 4, 1947. This date will be new to anyone who has known Johnny Dyani. The date itself speaks about what was to be one of the main themes in his life: alienation. Not only did Johnny never know his biological mother, he didn’t even know his own birthday. When he was to leave the country and needed a passport, it was issued with December 31, 1947, as his date of birth. Later in his life, after he had come to Europe. Johnny somehow got the idea that November 30, 1945, was a more likely date for his birth. I have not been able to find out who suggested that date to him or what made him believe in it. Johnny kept the 1947 date in his passports for the rest of his life but quoted 1945 in all conversations and interviews, and he celebrated his 40th (and final) birthday on November 30, 1985.” Lars Rasmussen, ‘When Man and Bass Became One’ in Mbizo – A Book about Johnny Dyani (The Booktrader, Copenhagen 2003).. His instrument was a piano, but he was later attracted to the bass which, to him, has the deep notes resonant of the folk choirs back home. In this profile, I trace some of the influences that made him a great artist.

Freedom was the lodestar of Johnny Dyani’s life. He sought it for both his country and his people. He sought it also in his chosen career — in music.

Johnny Mbizo Dyani’s path to a career in music began like that of many others in the bustling townships of South Africa’s urban areas. He was fortunate in one singular respect — an early exposure to some of the leading musicians from the black community. His home, in East London, had for years been a regular stop-over for musicians on the road. He thus rubbed shoulders with seasoned professionals from an early age. Much of their skill was passed on to the impressionable youth. He displayed a precocious interest in the double bass, first picking up tips from itinerant musicians, then beginning to play with his peer group. The formative influence at this point in his life was Tete Mbambisa, an exceptional pianist, composer and arranger. It was as part of a quintet of singer/dancers, led by Mbambisa, that Johnny made his stage debut. Throughout his musical career singing remained one of his great passions.

Touring the coastal cities along the garden route, the quintet made a big hit with their spirited and highly original renditions of such American jazz standards as A String of Pearls, Three Coins in the Fountain, My Sugar is so Refined, This Can’t be Love; and others. It is a lasting testament to both his talent and perseverance that from these small beginnings, in non-amplified, dingy, drafty dance-halls, that he grew into a much sought-after international talent.

During the 1950s, as Johnny entered his teens, the most influential band in East London was led by Eric Nomvete. Playing a very eclectic repertoire that incuded jazz standards from the swing era, waltzes, the Tango, mbaqanga, be-bop and host of other dance-hall favourites, this band directly impacted the moulding of his taste and the breadth of his musical vision. But the decisive influence on Johnny’s musical career came from outside his immediate environment.

In Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, Johannesburg, Queenstown and East London a tiny fraternity of black musicians found an affinity with the pioneers of the modem jazz movement in the United States — Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. They were avid collectors of records and sheet music and incorporated the influences of the be-bop style in their own music. Many of the figures that have since become legendary in black South African music were members of this group. One thinks of names such as Kipple Moeketsi, McKay Davashe, Sol Klaaste, Christopher Columbus Ngcukana, Cups and Saucers Kanuka, Gideon Nxumalo, and, amongst the younger generation of musicians, Dollar Brand, Duda Pukwana, Chris McGregor, Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa and Johnny Gertze.

The modern jazz movement struck roots in the major metropolitan areas, especially the port cities of the Cape, through which the music journals and records from abroad were imported. It was a movement of the young, daring and talented. From the beginning modern jazz was a minority taste. patronised by black workers and intellectuals in the urban areas, a growing number of ‘off-beat’ white students and artists, and the occasional music business impressario. Its breeding grounds were centres such as Dorkay House in Johannesburg, run by the Union Artists, the Ambassadors Jazz Club in Cape Town, the Blues Note cafe in Durban and various university campuses.

In the South Africa of the 1950s the very notion of an African making a career in music was legally impossible. That a musician should hope to prosper by playing modern jazz, was even more far-fetched. But despite this, the pioneers of the movement were prepared to brave the worst adversities. Perhaps it was their youth; that most did not have the additional responsibility of raising a family enabled them to steer the perilous course between the shoals of racist laws and discriminatory practice. Life itself was a tight-rope act, governed by numerous dodges to circumvent the pass laws, the Urban Areas Act, and the Group Areas Act. All this made it hard to form stable bands or groups. Record dates were even harder to come by.

At the time, the major outlet for black talent was the “African Jazz and Variety Show”, owned and managed by a musical huckster, Alf Herbert. Most of the adherents of the modern jazz movement had passed through the mill of “African Jazz” where they had learnt the bitter lessons of cultural exploitation and artistic prostitution Herbert was notorious for. Their determination to preserve their cultural and musical integrity was in great measure a direct consequence of this experience.

One of the first stable modern jazz groups was made up of Kipple Moeketsi (alto sax), Hugh Masekela (trumpet), Jonas Gwangwa (trombone), Dollar Brand (piano), Johnny Gertze (bass) and Makhaya Ntshoko (drums). Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim) at the time also led his own trio, composed of Johnny Gertze and Makhaya Ntshoko, which regularly featured at the Ambassadors Jazz Club in Cape Town.

It was into this milieu that a bright student at the South African College of Music entered. His name. Chris McGregor, the Transkei-born scion of white missionaries. Chris was strongly influenced by the intellectual currents affecting France and the United States in the period immediately after the Korean War. He had become a well-known figure in Cape Town artistic circles as an exponent of existentialism and a modern jazz pianist. Using both the campus of the University of Cape Town and the fledgling jazz clubs around Cape Town as his base, he had integrated himself with a group of black musicians from the townships of Cape Town. Among this number were Cups Kanuka, the tenor saxophonist from Langa, with whom McGregor often shared the stage; Christopher Columbus ‘Mra’ Ngcukana; Dayanyi Dlova, an alto sax man; Sammy Maritz, the bassist. From 1961 he developed a lasting and extremely fruitful relationship with an alto sax player from Port Elizabeth. Duda Pukwana.

1960, the Sharpeville Massacre, the banning of the ANC and the declaration of the State of Emergency, inaugurated the campaign of massive repression that characterised the next two decades. The regime definitively cut off all avenues of peaceful struggle, forcing the national liberation movement to reassess its entire strategy. An aspect of the new strategy was a concerted campaign to isolate the apartheid regime in the world community. This necessitated the creation of the African National Congress’ international mission to co-ordinate and plan this campaign. The decade of the sixties was to be the turning point in Johnny Dyani’s life.

The nodal moments were the Jazz Festivals in Moroka in 1962 and 1963. At the ’62 Moroka festival, Chris McGregor fielded a septet drawn from Cape Town musicians; Dudu Pukwana came with a quintet, the Jazz Giants, including Nick Moyake on tenor and Tete Mbambisa on piano. A second group from Cape Town, the Jazz Ambassadors, led by Cups and Saucers Kanuka, included Louis Moholo on drums. Eric Nomvete from East London brought along a group that included Mongezi Feza on trumpet. All these were promising musicians, destined to win recognition not only in Johannesburg but internationally. In 1963 they were all brought together in one group, the Blue Notes, led by Chris McGregor.

The Blue Notes came into existence after the other members of the group ‘discovered’ Dyani while playing a gig in East London. Somewhere along the line, at an afternoon session in Duncan Village, a bold teenager asked to sit in with the band. Rather taken aback, but always ready to explore new talent, the band agreed to allow Johnny one or two numbers on a borrowed bass. After the first tune they played together the others on the bandstand realised that they were not dealing with some brash upstart, eager to impress his friends by sitting-in with old campaigners, but rather with a bold and immensely gifted bassist. It went without saying that they would enrol Johnny in the Blue Notes.

By 1963 each of the members of the band had evolved and grown tremendously. Chris McGregor, the leader, had continuously interacted and sought opportunities to perform with all the key musicians of the modern jazz movement since the late 1950s. His academic training had contributed to his skill as an arranger and transcriber. Playing with the likes of ‘Mra’, Kippie. Cups and Saucers, Dudu, Mankunku, Johnny Gertze and McKay Devashe had helped him to grow from a callow emulator of Bud Powell into a definitively South African pianist, partaking and contributing to the cosmopolitan melting pot of its evolving culture. The meeting in East London was another fortunate break for Johnny Dyani because the Blue Notes were preparing to go overseas. The trip materialised in 1964.

Their popularity and prestige had brought them to the notice of the European jazz critics. Consequently, the band was invited to play at the Antibes Jazz Festival, in the south of France, during the summer of 1964. Assisted by a grant raised from amongst the Rand mining magnates, the band left for Europe in mid-1964. Antibes was to be the gateway to a new world for all of them.

After its initial ‘hit’ impact at the festival, the Blue Notes had to weather the storms and chilly winds of the ‘free marketplace’, dominated by the entrepreneurs of the music business whose chief concern is business and not the promotion of talent. The first three years after Antibes were the hardest. Flushed with a perhaps naive enthusiasm for the relative freedom of Europe, the musicians fell victim to one flim-flam artist after another. To all intents and purposes the Blue Notes ceased to exist in 1965. Nick Moyake opted to return to South Africa. Johnny Dyani and Louis Moholo joined up with the US saxophonist Steve Lacy and became stranded in Buenos Aires. Dudu, Mongezi and Chris made their way to London where they tried to make ends meet with intermittent club dates.

Somehow the dispersed members of the Blue Notes managed to retain their old loyalty to the conception of the original group. Huddling together for warmth in London, the core group financially assisted the two prodigals from Argentina back to London.

By the time Dyani and Moholo came back to Europe in 1967, the modern jazz school had undergone its most far-reaching metamorphosis since Parker and Gillespie at Minton’s in the late 1940s. The names associated with these changes are those of Ornette Coleman, an altoist from Texas; John Coltrane, a tenor man, formerly with the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band, later with the Miles Davis Quintet; Eric Dolphy, a former Mingus sideman; Albert Ayler, an altoist from New Jersey; and Archie Shepp, tenor saxophonist from Philadelphia.

The accent among these innovators was on freedom.

Freedom, they said, could be attained by breaking out of the conventions of be-bop and socking out new modes of expression through total improvisation. They forcefully re-asserted the African musical idiom, borrowed freely from Indian, South American and contemporary European so-called “New Music”. For good measure they threw in elements from the Shamanism of Asia and North America for further experimentation. It was called the ‘New Wave’ or ‘Avant Garde’.

Individually and collectively the members of the Blue Notes had kept abreast of these developments. The core group in London was already making a mark on the Avant Garde scene where they had a regular weekend gig at Ronnie Scotts ‘Old Place’ in Soho. On their first weekend back in London after their Buenos Aires debacle, Dyani and Moholo demanded to be allowed onto the bandstand after the first set. In sensational second and third sets, the reunited Blue Notes set the club on fire. There was an evident empathy between the musicians despite the years of separation. Critical acclaim was not long in coming, followed by a record date early in 1968, the outcome of which was an album, Very Urgent on the Polydor label.

Very Urgent, which features compositions by Dudu Pukwana and Chris McGregor, was expressive of the mastery of the musical idiom of the avant garde by the leading South African musicians in Europe. It remains a collector’s item.

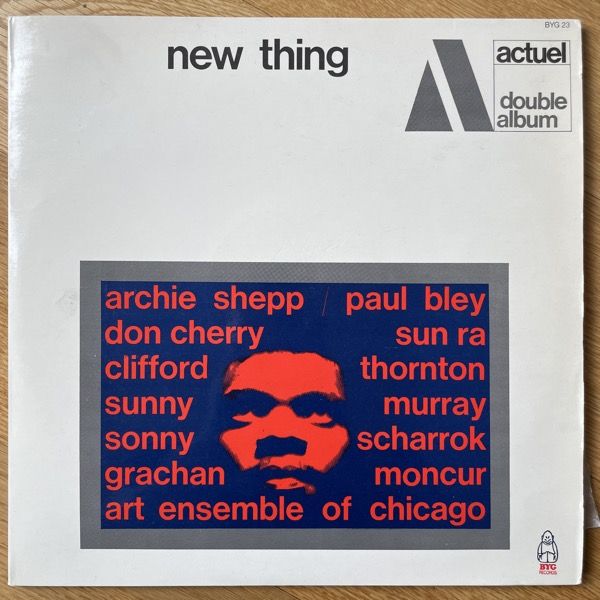

During the succeeding years the differing directions sought by the individual members of the reunited Blue Notes contributed to the dissolution of the group. By 1970 Dyani was freelancing with various British, Continental and American groups in addition to leading small groups of his own in and around London. The extreme fluidity of the avant garde assisted his development. Stable groups were the exception rather than the rule as musicians from the USA, South America, Europe and Africa sought each other out for the chance to perform together and thus share experience and ideas in the act of creation. For a little while Paris became the centre for avant garde American musicians, who coalesced around the BYG label (Actuel).

The strength of the avant garde was that it arrived at a moment when developments in the electronics industry made recording facilities more readily available to small scale operators. This effectively broke the monopoly over reproduction formerly held by the record companies. The musicians, too, were more concerned to effect direct communication with their audiences rather than transmittal through radio and the record industry. Small clubs proliferated, concerts, festivals and loft gigs, closely associated with the changes in lifestyle, had also undermined the star system so assiduously cultivated by the promoters and music hustlers of the 1950s.

Johnny Dyani made his own distinctive contribution to the contemporary cultural climate of a healthy cosmopolitanism, reflective of the recognition of the universality of aesthetic values and the need for humanity to share its common cultural heritage.

Dyani’s first album featured Mongezi Feza plus a Turkish master drummer, Okay Temiz. This was to be characteristic of all his subsequent albums. Caribbean, American, Danish, South African. North African and Swedish musicians all, at one time or another, were drawn into his various small bands, the most recent of which was called Witch Doctor’s Son. He gave his work an explicitly political tone in the eighties, with albums such as Mbizo (1983) Born Under the Sun (1984) and Angolian Cry (1985). He also made an invaluable contribution to a most fruitful collaborative relationship with Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim), the product of which was two classic albums, Good News from Africa (1974) and Echoes From Africa (1979).

Among his other musical co-workers can be numbered some of the most outstanding exponents of the avant garde school. These include Don Cherry, Jon Tchicai, Oliver Johnson plus his old colleagues from South Africa, Dudu Pukwana, Louis Moholo and Chris McGregor. The memorial album, dedicated to the memory of Mongezi Feza, Blue Notes for Mongezi (1975), and a subsequent album, Blue Notes in Concert (1977), are glowing examples of the band’s mature interpretation of the avant garde idiom.

After 1973 Johnny Dyani once again moved from London, settling first in Denmark. then in Sweden. It was from here that he led his most stable group, Witch Doctor’s Son, a band with a heavy mbaqanga sound, which became a regular feature at Jazz Festivals throughout western Europe. It was during a gig in West Berlin, over the weekend of October 25th, 1986, that Johnny Dyani collapsed on stage.

Throughout his musical career, Johnny had actively associated himself with the liberation struggle. During Festac ’77 in Lagos. Nigeria, he was part of a small ANC delegation. At the Gaborone ‘Culture and Resistance’ Festival, he proved an articulate spokesperson on behalf of the musicians in a number of panels. In Scandinavia, he was an active member of the ANC regional structures, often contributing his services to raise funds for the movement.

In Johnny Mbizo Dyani’s tragically young death, we come to the end of a brilliant chapter in South African cultural history. It marks the final disappearance of the Blue Notes. Nick Moyake died in Port Elizabeth in 1969; Mongezi Feza died in London in 1975 and on 24th October 1986, Johnny Dyani collapsed on stage in West Berlin. Chris McGregor died on 26 May 1990 and a month later Dudu Pukwana passed on 30 June 1990. Louis Moholo-Moholo is the last man standing.

During his all-too brief life Johnny Dyani left an indelible imprint on black South African music and the international jazz scene. Through his music Johnny managed to reach out to global audiences — touching their hearts with that subtle and sensitive blending of the hope, sorrow, desires and struggles of the South African people. In his music one could hear the rhythms of protest, so eloquently expressed in the work songs of the unskilled labourers; one could feel the moving pathos of the songs of widows of the reserves; one could be swept up in the spirit of defiance and revolt conveyed in the surging freedom songs. But above all, his music resounded with a joy in life, which is at the core of our musical traditions.

Johnny Dyani, like most of our musicians, was sprung from the loins of the black working class. He was, in the best meaning of the term, a man of the people. From an early age he was possessed of a quiet dignity and self-assuredness, endowed with a vast capacity for hard work and sustained effort. These were the qualities he brought to his first love — music — which was his chosen career.

Johnny was never a pompous or conceited person. Amongst his friends and colleagues he was known for his wit —a digging, ribbing sense of humour so common in the Eastern Cape.

Unlike many of his peers, he was perhaps fortunate in having had the opportunity to go abroad. In the world beyond South Africa’s borders, despite the many hardships he suffered.. he was at least free from the ubiquitous racial barriers, restrictions and constraints that have smothered so many other talents amongst our people. As we cast our eyes back over the life and times of this outstanding musician who died so young, we can feel proud of a record of no mean achievement. Yet this same record serves to remind us also of the thousands of others who never even received the opportunity to develop their potential, because of the system of national oppression that held our country for so long in thrall.

Johnny Mbizo Dyani was not the type of artist who subscribes to the notion that ‘the double bass is mightier than the sword’. He knew from his experience as a man, and through his sensitivity as an artist, that the freedom he sought could not be achieved solely in the key of B flat or C major. He clearly understood that freedom, for the artist and in the arts, is inextricably bound up with freedom in society. It was this recognition which determined the path to which he hewed, as a politically committed artist.

This article was first published in Rixaka #4, 1988. It is republished in herri by kind permission of the author.

Feature Image © Graham de Smidt

| 1. | ↑ | “We don’t know where exactly Johnny was born, although it was probably in the home of Ebenezer Mbizo Ngxongwana and his wife Nonkhatazo. We don’t know who were present, and even the date of the event has been under discussion. According to the Home Office in King William’s Town, Johnny was born on June 4, 1947. This date will be new to anyone who has known Johnny Dyani. The date itself speaks about what was to be one of the main themes in his life: alienation. Not only did Johnny never know his biological mother, he didn’t even know his own birthday. When he was to leave the country and needed a passport, it was issued with December 31, 1947, as his date of birth. Later in his life, after he had come to Europe. Johnny somehow got the idea that November 30, 1945, was a more likely date for his birth. I have not been able to find out who suggested that date to him or what made him believe in it. Johnny kept the 1947 date in his passports for the rest of his life but quoted 1945 in all conversations and interviews, and he celebrated his 40th (and final) birthday on November 30, 1985.” Lars Rasmussen, ‘When Man and Bass Became One’ in Mbizo – A Book about Johnny Dyani (The Booktrader, Copenhagen 2003). |