INGE ENGELBRECHT

Tribute to Sacks Williams: A composer from Genadendal

The Williams family greets me at the entrance to the Moravian church in Grassy Park. They speak to me as if I am family, a gesture that blesses my sad heart especially because we had never met before this day. I walk inside and I see the (open) coffin to my right at the back of the church for mourners to view “the body”. I don’t know where I expected it to be, but seeing it makes me stop in my tracks for a moment. The moment feels longer than the two seconds it actually takes me to decide whether I should look or not. Why am I even wondering? I never look – it is just too jarring and macabre. I slink past with my gaze deliberately fixed towards the pulpit, making sure I catch no glimpse of anything to my right. I am unexpectedly confronted with a childhood memory of my own great-grandmother’s funeral in Keimoes where, as a five year old, I could see a grey-white strand of hair sticking straight up from inside her coffin. I walk to the middle section of the socially distanced church and slide down past two mourners in the mostly empty pew to the farthest end. The coffin seems so tiny, so tight around Mr Williams’ large statured body, the way I remember him. It makes me angry and sad. Where is the large, regal mahogany casket befitting this enormously respected man? I close my eyes and try to regulate my breathing behind my black mask. I finally open the programme with Mr Williams’s face on the cover and scan through the morning’s proceedings. And then I understand and accept the coffin, and am strangely comforted: Mr Williams is to be cremated.

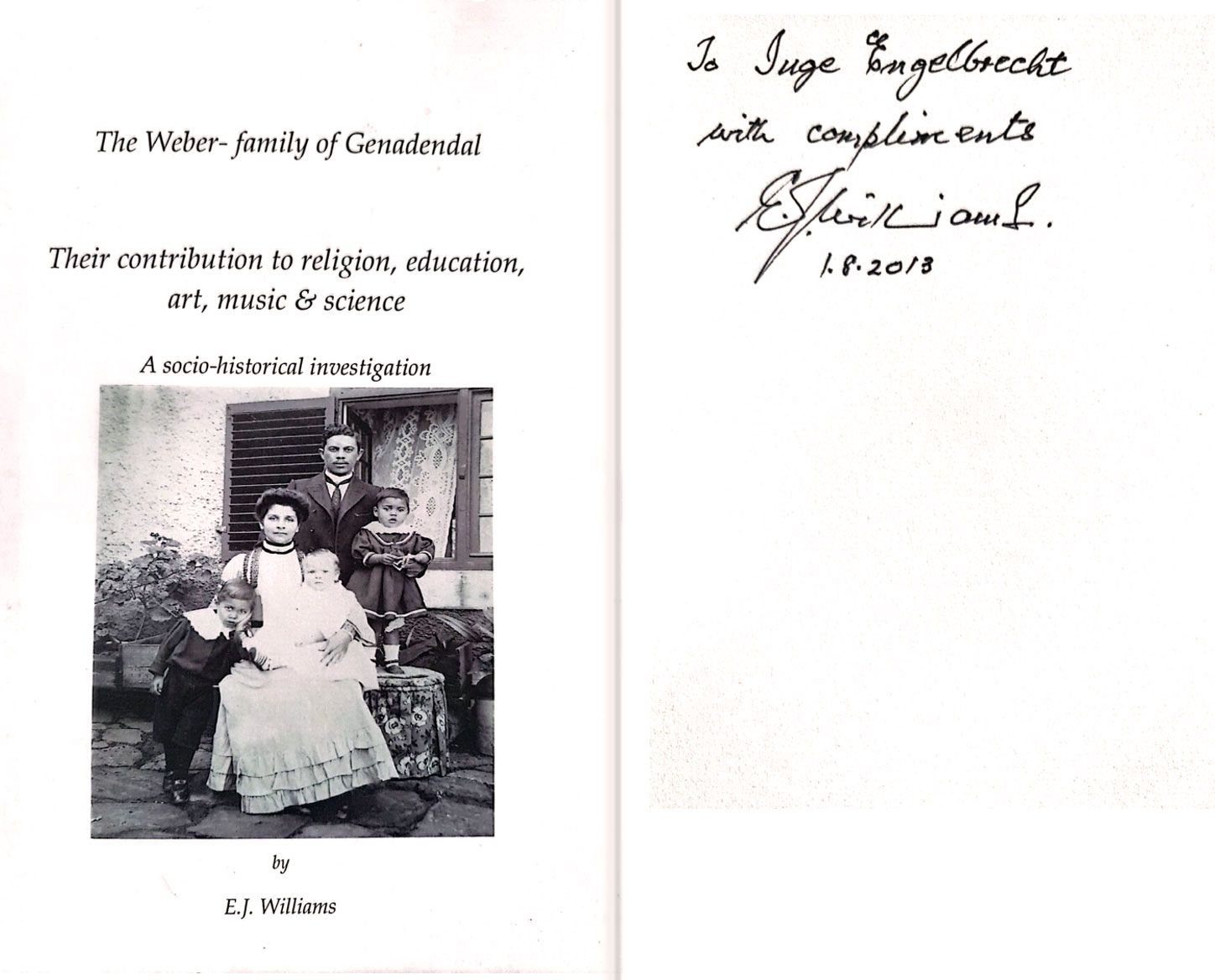

I met Mr Sacks Williams in 2013 in the Botanical Gardens in Stellenbosch. He had agreed to be one of the subjects in my master’s research on three composers, including Messrs Dan Apolles and Dan Ulster, who both had strong ties to Genadendal. Mr Williams spoke with conviction and moved with a deliberateness befitting a man who knew who he was and where he came from. He had brought along a few copies of the book he had written about his family’s history and gifted myself and my supervisor at the time, Stephanus Muller, each with a book that he signed on the spot with his own fountain pen which he took from his shirt pocket. He would later in 2017 proudly sign, with that same pen, the inside cover of my completed thesis, which he had paid to be printed and bound for me, himself and Mr Dan Apolles.

Ezechiel John Whall Williams, affectionately known to his family and friends as “Sacks”, is a descendent of Johann Heinrich Weber (c. 1735-1808) from Honnef, Germany. His great-grandson, Eduard Franz Weber, had become involved with an indigenous girl, Anna Catherina Coerland, and after refusing to break off the relationship, he was disowned by his family. He moved to Genadendal where he would marry Anna in 1834. From this union five children were born in Genadendal, and Sacks Williams is a direct descendant of the third son, Godlof Weber.

Although not born in Genadendal, but in Port Elizabeth, in 1943, Mr Williams was a descendant from the mission station and its music traditions. He trained as a schoolteacher at Bridgeton Training School in Oudtshoorn and specialised as an art teacher at Hewat Training College in Cape Town. For many years, Mr Williams served as the school principal of several schools, after which he was approached by Professor K.T. August to join the lecturing staff of the Heideveld Moravian Theological Seminary, where he lectured in church music and liturgy. Mr Williams retired from teaching in 1993 and resided in Grassy Park with his late wife, Elizabeth, until a few years ago.

Throughout his life Mr Williams had been involved in music activities, serving as choir master, organist, and musical director at his church in Grassy Park, where he also founded a youth brass ensemble. During his years as teacher in Piketberg, Williams regularly organised choir festivals for the surrounding schools and arranged music for his own school’s choir. As local music teacher he trained several choirs and brigades of the Dutch Reformed Church Congregations of Piketberg and Saron for the annual choir competitions, where he also served as accompanist to these choirs. In 1982, Mr Williams was asked by the Provincial Council of the Moravian Church to lead choir workshops, with the focus on church music, at the Shiloh mission station in the Transkei. He was also one of the founding members of the Moravian Choir Union of South Africa (MOCUSA) and served on the board as vice-president until his retirement in 1993.

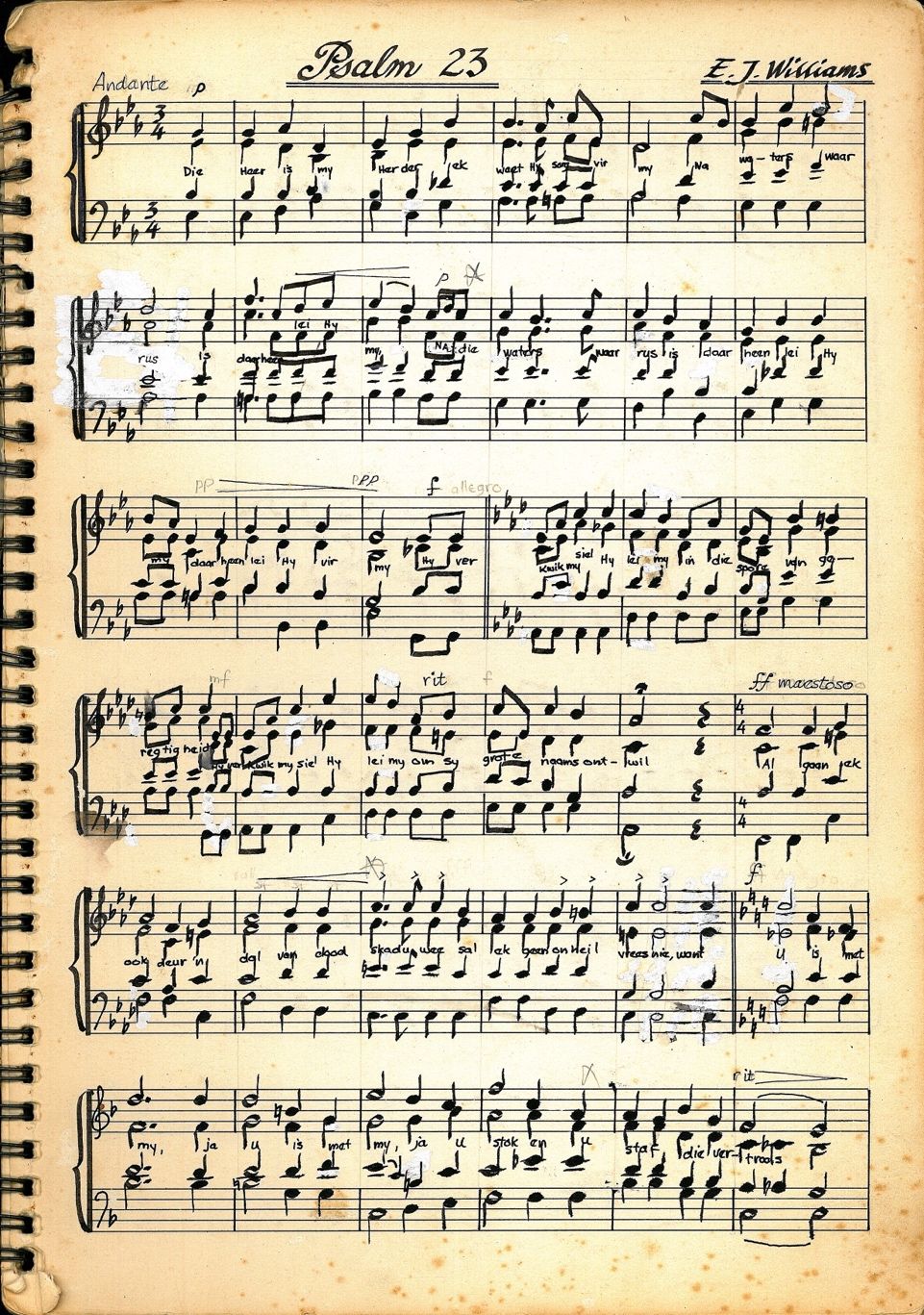

Although Mr Williams had a rudimentary training in music, receiving piano lessons and basic organ technique as a boy, he never studied music at tertiary level or received formal training in composition. He has, nevertheless, arranged works for instrumental ensembles, set texts to music, and composed original works that have been performed at celebratory festivals by the Moravian church, and has a compositional ouevre of more than 30 works composed over a period of roughly 35 years. As he put it, his sole composition teachers were Bach’s Preludes and Fugues, the second movements of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, and specifically Mozart’s simple and cheerful melodies. Sacks Williams was a religious man and most of his works were written for religious purposes. His composition catalogue consists primarily of church hymns, or tunes, two of which are published in the current Moravian Choral book, namely Psalm 23 and Come let us Sing. Some of his compositions have also been used for specific festivals commemorating the missionary work of the Moravian church.

During my first interview with Mr Williams, I asked him whether he considered himself to be a composer. He appeared to be quite uneasy about claiming this title for himself and deferred to Stephanus Muller, who was present at our first interview, presenting us with his sheet music to assist in the valuation and conclusion. He did, however, position himself more confidently between a “liedjieskrywer” and a composer, but not quite a fully-fledged composer.

Sacks Williams wrote his first composition when his father passed away in 1983. He told me the story of how, when he entered the room where his father’s body lay, he saw an expression of contentment on his father’s face.

Dit is toe ek in die vertrek kom en ek die liggaam van my pa sien lê, na hy skielik gesterf het, en ek toe nou die uitdrukking op sy gesig sien, toe dink ek: maar kyk, as jy dan nou so tevrede kan lyk, nadat jy jou hele lewe lank die Here gedien het, dan is dit mos die moeite werd as jy kan sê ‘die Here is my Herder.’

(Interview extract, 2015)

He set the text of Psalm 23 to music in honour of his father.

Mr Williams also set Psalm 116 to music and dedicated this work to his mother, Fredericka, with the caption: Vir Pats (her nickname). According to Mr Williams, Psalm 116 was a favourite Psalm of his mother and she frequently quoted verse 12: “Hoe sal ek die Here vergoed vir al sy weldade aan my?” He set two versions of this text to music. The second version of this setting is my favourite composition by Mr Williams.

Through the years, Mr Williams’s compositions have been performed for different occasions and events, mostly in spiritual settings. In 2018, two of Mr Williams’ choral works were performed by the Stellenbosch University Chamber Choir (SUCC), under the direction of Dr Martin Berger, as part of their repertoire for the annual Woordfees festival in the Endler Hall.

And two years earlier on 29 June 2016, Messrs Williams and Apolles performed some of their own compositions in the Fismer Hall of the conservatorium at Stellenbosch University and were recorded for posterity by Aryan Kaganof.

Although Mr Williams was reluctant to call himself a composer, it is clear that Sacks Williams did indeed have a distinct and absolute idea of who he was as a musician and composer. He had always been unambiguous about why he ultimately composed and arranged music: Soli Deo Gloria. His compositions he considered part of his spiritual life, composed from a place of religious conviction, and solely to honour God. He was insistent that those who perform his works understand the reason for its creation because he composed about eternal, Godly values and things that had meaning to him.

Sacks Williams’ ultimate desire was that his beliefs be reflected in his music, music he considered deeply rooted in a Western tradition and in the musical traditions of Genadendal.

In the years after the completion of my master’s thesis, Mr Williams and I remained in contact. Our conversations ranged from my current research and his own new compositions, to his mock concern about why in every social media picture I supposedly post, I always have a glass of wine in my hand, and the sorry state of my love life. We laughed a lot during these conversations, which usually lasted around 20 to 40 minutes. He called me when his wife passed away, and when he was diagnosed with cancer, the latter call coincidentally taking place while I was in Genadendal. On 8 February of this year, we spoke about a possible date for me to visit him. He and his wife had moved in with his eldest son and his family a while ago before Mrs Williams’s passing, and he told me about how grateful he was to his son and daughter-in-law. He asked me to keep his music safe and share it with whomever was interested. But he insisted that I wait until he felt and looked better before we schedule the visit. He was going to call me to set up a date. That was our last conversation.

As the final part to this tribute, I end with an extract from my master’s thesis, a quick exchange that took place between me and Mr Williams the day after the June 2016 recordings in the Fismer Hall. I have chosen this extract as an illustration of, and a glimpse into, the special friendship Mr Sacks Williams and I had, and ultimately, for myself, as a memorial stone of the extraordinary journey we would come to share.

The next morning, I get a call from Mr. Williams, again thanking me for the previous day. The main reason for the call, however, is to ask whether I am satisfied with the recordings. He had realised that he and Mr. Apolles have very different styles and techniques, and he had noticed that his left hand plays slightly before his right hand. He wants to make sure that it is fine with me, but if I am unhappy with the recordings, he will come back and record his pieces again. I assure him that Stephanus and I had noticed that that is the way he plays upon our first visit to his house. I also tell him that we are aware that he performs on both piano and organ and that the mechanisms of these instruments differ, therefore they each need a different technique, and that that could be the contributing factor to this unique style of playing. I reassure him that what he did and how he did it was exactly what we had hoped for and expected of him, nothing more and nothing less. This seems to assuage his concerns, after which the old, jesting fellow I have come to know reappears. He ends our conversation by saying: “Girlie, jy weet nie hoe ’n groot deel van my lewe jy geword het nie.” … I don’t know what to say. Thankfully, he breaks the silence with an uncomfortable joke, to which I laugh, comforted by this familiar jocosity we’ve both become so used to over the past two years.

Ezechiel John Whall “Sacks” Williams (1943-2022)

Gaan wel, Meneer!