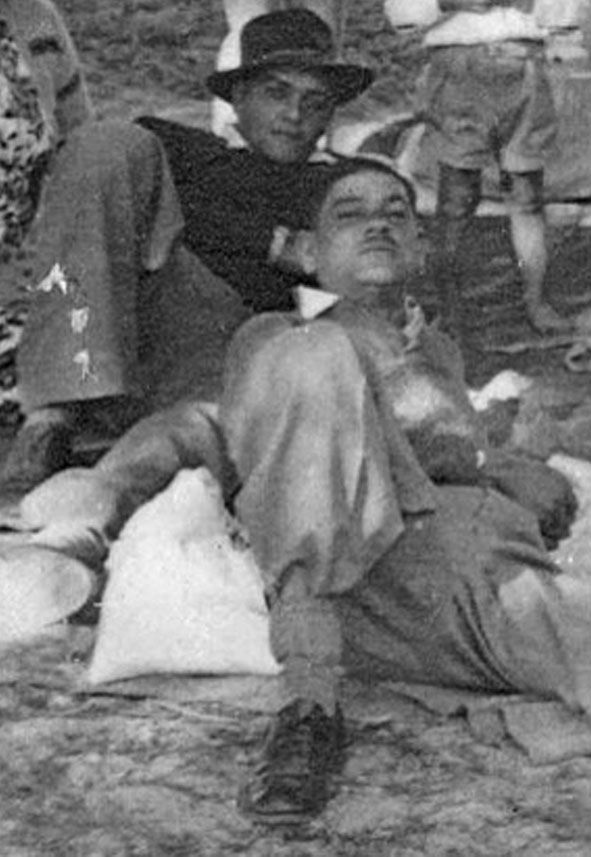

This picture invokes happy, but also painful memories. It was a time when Apartheid was at its worst. Yes, for the older people in the picture then, for it affected them more than the children. With arms folded in the forefront of the picture and a stubborn expression on my face, it shows an attitude of defiance ever since this photo was taken by my uncle, a keen amateur photographer.

My uncle “escaped” later to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, because of a radical political stance, like most of the guys where I grew up. His darkroom/studio was in the backyard of our house, which we, as a family had to vacate to a complete new area because of the cruel illegal Group Areas Act.

A small room like this was an invitation for a little boy like myself with bottles of chemicals and rolls of photographic paper. With my kind of innocence and sense of misadventure, I used to wrap a piece of paper round some body parts including my little willy just to see the depiction on paper as it was exposed to light. But alas, it was just a dark/light spot on the paper and on my skin, a “blemish” that later gave me the name of “Cape Coloured”.

This boytjie, on the forefront of this picture with arms folded, and a very stubborn expression on his face, shows some irritation or dissatisfaction. It depicted a stance that would become more militant later. I’ve always been like that. Now I’ve mellowed out and sort of accepted my environment and circumstances. My interpretation then would have been quite different from today because life in all its “glory” happened in the meantime. But yes, of course, this boy’tjie from Stellenbosch was exposed to all kinds of emotions and experiences, as I am sure many of us were as such (both black and white) under the yolk of Apartheid.

In a deeper reflection on this picture as an adult now, with lots of memory to fill a huge container, the impact is felt, even more, because my mindset and my perspective now, stays on a biting edge, meaning a stance the same as in the photo, but based on justice and total freedom!

Allow me thus the following experience in the context of where I grew up, at least for fifteen years, until the yellow monsters came, named Caterpillars. Their main job was to destroy houses and, thus, a community.

We stayed in the centre of Stellenbosch, in a street that ran through the University complex, then called Van Ryneveld Street. The white municipality took the “liberty” to change the name just to Ryneveld Street to establish their false power and to prove a point!

A name that stuck in the Community’s consciousness for this space or living area is “Die Vlakte”, (Afrikaans word), basically because it looked/felt like District Six, at least in spirit. The people from “Die Vlakte” were moved out of the city centre, but not out of Stellenbosch so their identity as “Stellenboschers” was not affected, yes then, without the power and voting rights.

Residents were displaced to two major areas, Ida’s Valley and Cloetesville, on the outskirts of the main town and not all over Cape Town as was the case with District Six. However, there were no facilities erected for coloured and black people in the city centre, no places where they could eat and no restroom facilities, and no restaurants that would serve them, unlike the rest of Cape Town, where separate amenities were erected.

The financial loss for the community of Die Vlakte was great, not only due to the fine quality of some houses but the sharp rise in property value near the university as well as the business centre of Stellenbosch.

Most homes were large and some properties were over a 1000 m2. Professional people who lived in “Die Vlakte” were the most severely affected as they had larger properties and thus much more to lose. The Group Areas Act made no distinction between the different socio-economic classes within the “coloured” community. The use of the following buildings after the Stellenbosch removal is an indication of the harshness of the forced removal:

The Volkskerk School was demolished and replaced by a local white business.

The Dutch Reformed Mission School (Latsky School) was destroyed to make way for a white restaurant. The James Higgo School was given to the airforce in Stellenbosch.

The Methodist school was used for a white pre-primary school, named De Kleine Bosch.

The Anglican school was used by the Stellenbosch traffic department.

The following congregations lost the use of their buildings:

The Volkskerk Church became St Paul’s church with a majority of white members.

The congregation of the Dutch Reformed Mission Church was moved to Ida’s Valley in a church building in Rustenburg Road 18.

The congregation of the Methodist church in Plein Street was moved to Ida’s Valley in Bloekom Street.

The following social comment comes from the local Imam:

Culture develops largely from social, economic, and political conditions that prevailed at a particular time. One of the many tools utilized by the colonist agenda was to portray most of Africa as a continent without a culture or at least as people with an “inferior” one, whatever that may mean. Embedded in the minds of the colonialist was the fact that people were people without a future. Post-colonialism revealed the opposite, Timbuktu being a typical case at hand, where a centre of learning was recently discovered. Another anomaly was that most of the history of Africa was researched and recorded by Europeans who could not entirely be free of anti-African bias.

Even sincere white researchers will never be able to capture or comprehend the destruction of the social fibre of a once community where even gangsters show a great measure of respect to the community at large – with their malevolence mostly concentrated on themselves. The economic impact of forced removals is beyond measure: churches and schools had to be constructed in close proximity to the community’s new areas of residence, transport expenses for those who once resided within walking distance of their places of employment or the railway station, etc.

Imam Fuaad Samaai (2006)

The males in the picture were manual workers at the time. It was “reserved” for those darker in skin. The whites used to sit in their Municipal lorries, reading Die Burger, while the blacks were digging ditches….

I often wondered about their (uncles) real station in life if we had stayed in a “normal” society. Maybe some professor of philosophy or law conforming to the norms of society. I might have been a convict in some jail….what!

With all the experiences weighing up with innocence it seems to be a good place with all the luxury goods in our jails nowadays, but nothing compares to freedom which you could only find in books and some graveyards of a thousand soldiers. What a contradiction! Yes, but an anti-war statement… and in our hearts, of course…

I guess this photograph gives an impression of joy and freedom, but not for the reason that you think, because we, judging by this pretty picture, were adept at playing our roles in society. Adapt or die!

No, but really, yes….Everything that is today could not be if it were not for that which was before.

We had to conform…another reason for me to be defiant; yes at this tender age, I suppose, on an unconscious level….

This picture comes out of our church’s archives. Every year, on the 14th of May it is our church’s birthday celebrating with outings to the sea or riverbank in the form of a picnic. This year especially, because our church is 100 years old, established in 1922. One underlying factor in the establishment our church, is politics; connected to the social interaction of people and poverty at the time, especially between the white settler churches and its darker skinned members. It led to a breakaway and the establishment of a new church, VOLSKERK VAN AFRIKA….a significant name…

Also in the picture are my three aunts, from left to right: Auntie Beaty, the first Kindergarten teacher in the so-called local coloured community and my main source of teaching me mathematics. I could not understand how 2 can go into six or how 5 can go into 8…it did not make sense, same as Apartheid, but it can also lead me to the fact that a majority of one makes sense to preserve your history by putting it on paper, like now!

Then there is Auntie Maggie, a dressmaker that use to make lots of beautiful dresses for the local Moslem women especially for their feast days. I use to play with the magnet that she kept in her dressing room to attract all the lost needles just as the lost souls during the Apartheid era.

Auntie Honey who could make the best food for white homes where she used to work as a cook… and the children in the picture were playing in the fields of the white God of the ruling class, restricted, not becoming who they really are.

And then my mother!

She was trying to make me conform by the way she looked at me as if she wanted to say “…come my boytjie, it is time to play your role in a big and wide and lily white South Africa…” And ever since then I’ve been fighting injustice… and now, ever so more.

Some time ago I was asked the following questions by a white learner for his school assignment:

1. Please give me some background information about yourself such as your occupation, your family and where you are living now.

Both myself and my wife are retired teachers with three daughters, Monique, Simone and Cleo. We are staying in Ida’s Valley, forcefully removed from a place called “Die Vlakte”, central to Stellenbosch, reserved for whites during the Apartheid era.

2. Describe your experience growing up in the apartheid era. What are some of your most prominent memories?

Growing up in Apartheid Stellenbosch can be at best be described as happy and contented, but yes, the negative impact of a racially divided society had its effect on the youth of the day. The first thing you noticed was that most places were reserved for whites and it sort of culminated into an us vs them mentality. We were growing apart and the separation at that time gave us a reason to stand our own ground, especially when we were called derogatory names like “hotnots”.

In our dorp were all kinds of notices which set us apart. Of course it affected me as a youngster when you want to enter a place only to be told by a notice board that it was reserved for whites.

One prominent memory is the running battles between white and coloured children.

Usually it started with name calling and an idea that we were children of a lesser God. Usually we shrugged it off, but yes, we literally started to throw stones. I landed up in hospital with a bleeding head wound.

Another memory that comes to mind is the exclusive terrain for whites at the University of Stellenbosch. We were not allowed to study there because of the colour of our skin.

3. How did the Group Areas Act affect you as a young person growing up in Stellenbosch?

Yes, it affected me as a young person, to the extent that I had to undergo some counseling, but this only happened later when I saw or became aware of its impact while writing my book.

4. What changes in your life did you have to make because of this law?

Change or adaptation came when my wife and myself had to study at separate universities. It also culminated in a different lifestyle with new neighbours in a new environment. Another change came when we had to move from our places of worship, schools, sport and entertainment. Basically it boils down to the trauma of forced removal.

The wider family response was like any other family that lived on Die Vlakte. But yes, we were weary of the law which was based on a unfair system and its impact on your day to day living. We were a disempowered people and we are still paying the price of this.

5. How did you and your family respond to the Group Areas Act and its implementation?

Well, not very well. A bad state of affairs. The law, supposed to set us free, but took away our basic freedoms.The older people use to come home with stories of discrimination and insult in their workplace. We were forced to look at the world with suspicious eyes and it still haunts us today.

6. How was your day to day life affected by this law?

Being a young person at the time, we sort of left it to the adults, but yes, they were fearful of the law and could not do anything.

7. How did the community around you act against this law?

Being a young person at the time, we sort of left it to the adults, but yes, they were fearful of the law and could not do anything.

8. When looking back now do you think you should have responded differently?

The key phrase here is “looking back”. Now, with hindsight, wiser and aware of Human Rights and how it plays out in the rest of the world, we should have responded differently. We can now be very clever, BUT at the time we were fearful of the harshness of the law and the Apartheid State. IT KILLED PEOPLE!

9. What did you learn about yourself in the way you responded?

A deep awareness of the love for people, even if they are from a different culture or race group, and the ability to place myself in the shoes of other people.

10. How has your experience during the apartheid years shaped who you are today?

As a relatively younger person it made me aware of human rights, writing about it and preserving the history of this place and time while opening up to you to tell the story of “Die Vlakte” in whatever form for the future generation, lest we forget.