Abstract

Unisa’s Ars Nova, which was succeeded in 2004 by Muziki: Journal of Music Research in Africa (under a very different editorial policy),started out in the late 1960s as a newsletter for students in the Department of Musicology (from 2002 the Department of Art History, Visual Arts and Musicology, and currently the Department of Art and Music). It soon developed into a modest research publication, initially intended for the department’s staff and students but later, from the early 1980s, increasingly eager to accept articles from a wider range of contributors. Although it became an accredited journal only in the late 1990s, its regular publication over a continuous period of thirty-five years makes it a valuable and fascinating resource for tracing some of the research interests and directions followed in South African musicology during that time.

Some of these interests and directions are explored here, and I show that, while sharing some international and local musicological concerns, the journal covertly if unconsciously sustained the notion of a ‘Western’ musical culture at the southern tip of Africa that can only be defined as imaginary. By virtually ignoring the full and arguably greater range of musics practised in South Africa, it preserved an attitude of cultural snobbishness that is open to interpretation to some extent as supporting the apartheid policies of the government of the time. Largely unruffled by the concerns of the ‘New Musicology’ until the dawn of the twenty-first century, it only gradually (if reluctantly) gave way to a more open policy once this had become politically correct.

From its inception in 1969 as a modest typewritten newsletter posted to registered music students at the University of South Africa (Unisa), the early issues of Ars Nova, edited by Socrates Paxinos,included short informative articles intended as supplementary study material and news items about staff members. That initial year saw four issues. The second issue of 1969 still bore the imprint ‘Departement Musiek’ (Department of Music) but with Newsletter 3 came several notable changes. The cover now sported a simple Mondrianesque graphic design bearing the words Ars Nova,and the little publication had expanded to twelve typewritten pages. Inside, the heading bore the inscription ‘University of South Africa, Department of Musicology’, signalling a departmental name change which was retained for 33 years until the amalgamation in 2002 with Unisa’s Art History and Visual Arts department. Issue 4 of 1969 included congratulatory messages from Percival R. Kirby, retired head of music at Wits University, and John Blacking, Professor of Social Anthropology also at Wits (until forced to leave South Africa for political reasons later that year), who noted that the newsletter ‘performs a valuable service, which is most welcome’. Its function as a modest newsletter soon began to incorporate broader musicological issues, and by volume 3 in 1971 contributions ranging from aspects of Baroque music, analytical viewpoints on Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and the relation between geography and music history had made their appearance. In 1974 contributions from writers not directly associated with Unisa began to be accepted for publication; the first of these were by Stefans Grové of Pretoria University and June Schneider of Wits.

By 1980, eleven years after its inception, the journal had ceased to function principally as a channel of communication between the Department of Musicology and its students. In 1981, no longer a ‘magazine’ but now proclaiming itself as ‘Journal of the Department of Musicology’, it had become a musicological publication with articles reflecting the research interests of staff members, book reviews and occasional contributions from beyond the department and the university. Postgraduate students too were represented, with articles based mostly on honours-level research and completed masters’ and doctoral theses. A number of these, as we shall see shortly, dealt with aspects of harmonic and formal analysis – a focus of attention supported by Van der Linde’s preoccupation with such areas and especially in terms of disputed analytical methodologies based on the theories of F.H. Hartmann. With very few exceptions it was only at the tail end of the twentieth century and the earliest years of the twenty-first that a handful of articles began to materialize dealing with new critical directions in international musicology.

The main editors were Socrates Paxinos until his departure in 1978 to become head of music at Pretoria University, Bernard van der Linde, head of the department for over twenty years and editor for sixteen years until his retirement in 1995, Derik (F.J.) van der Merwe in 1980, Rudolf van den Berg for a short period until his untimely death in 1997, and myself for six years (vols. 30-35) until the journal was replaced by Muziki in 2004. If Van der Linde’s desire expressed in his editorial of the 1990 issue for Ars Nova to return to its early emphasis on music education had failed to materialize, there seems little doubt that the journal played a useful if supplementary role to SAMUS in encouraging an interest in musicological research in South Africa during the last decades of the twentieth century.

Two surveys of articles published in Ars Nova have appeared. The first, in two parts and covering twenty-two years of Ars Nova from its inception in 1969 to 1990, was by Jolena Geldenhuys (1990 and 1991). It gives an historical but non-critical perspective on the journal’s development and editorial policy, and includes the titles of many of the articles. The second, dating from the final issue of Ars Nova in 2003 and written by myself, covered articles in the last thirteen volumes of the journal’s existence subsequent to Geldenhuys’s earlier surveys. These two surveys are helpful for anyone wishing to gain a general summary of the journal’s development and to examine general trends, but neither survey provides much analysis or critical assessment of the contents.

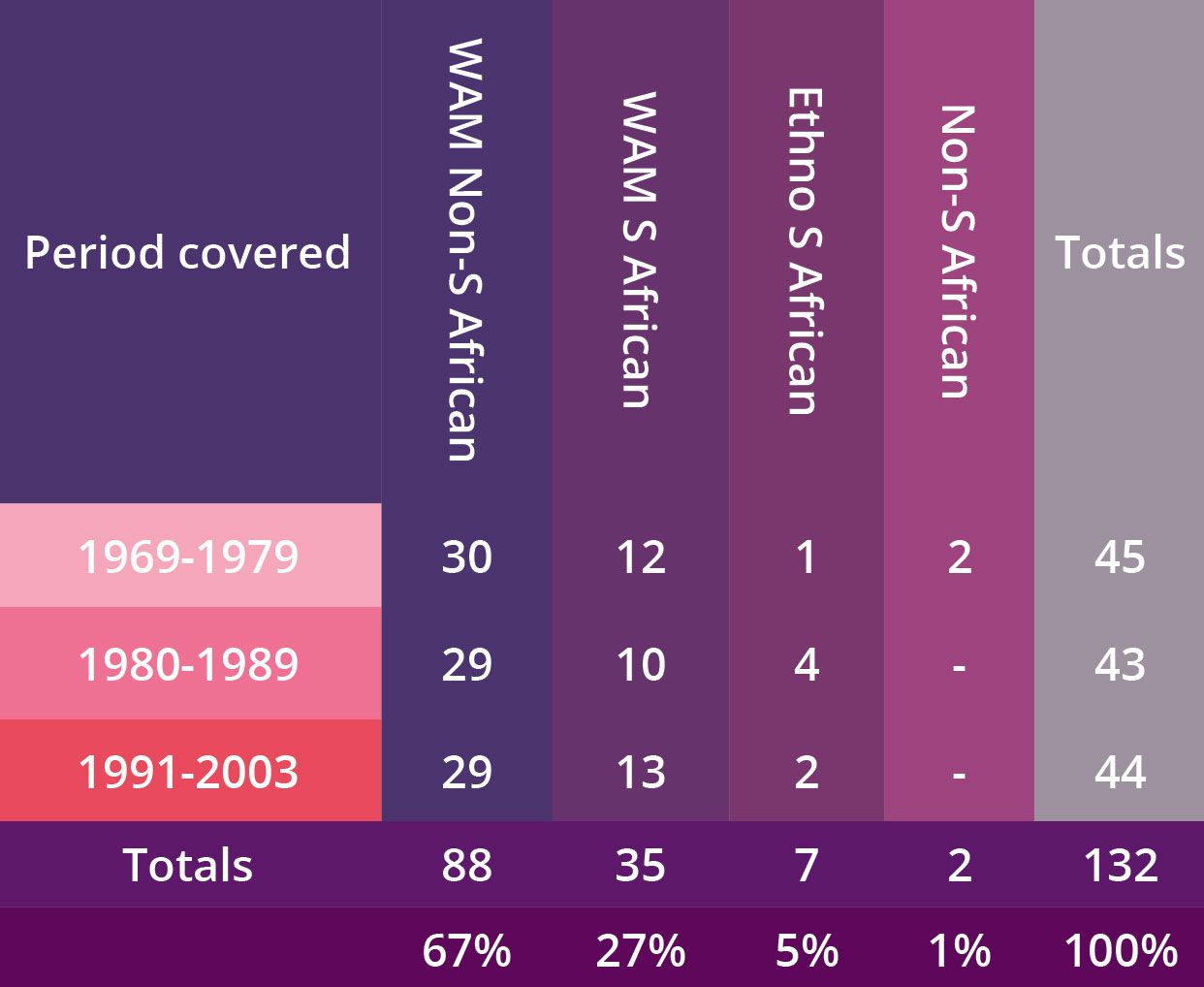

So let us now take a look at the topics of the research articles published in Ars Nova. Figure 1a gives us a simple breakdown of the broadest categories. Given the extremely conservative political climate of apartheid South Africa during the 1970s, 80s and early 90s, this initial analysis may not reveal any surprises; yet the articles submitted, selected and in some cases solicited for publication reflect fairly accurately the department’s conventionally conservative and largely positivist stance in pursuing an exclusively Western art music programme at that time.

Table 1b provides a further breakdown by subject matter of the 132 articles published from 1969 to 2003 (vols. 1-35); the reader should note that these are overlapping categories.

From these tables it is glaringly obvious that articles dealing with non-Western are thin on the ground: 93% WAM as opposed to 7% ‘Ethno’. Some of the reasons for this are examined further on.

Dissenting voices

There had been sporadic if muted dissension from within the department. As far back as 1973 Mary Rörich (1973, 41), then a lecturer on the staff, declared in an article on the work of Hugh Tracey:

Cultural research is surely the province of academic institutions … The future of African music research is in the hands of students and lecturers in musicology of the present decade. Do we accept the challenge?

Nine years later in 1982, in a report on the ninth South African musicological congress which had the theme ‘Musical education at university level’, Douglas Reid (associate professor in the department at the time) noted several perceptive comments by Christopher Ballantine, Khabi Mngoma and Alan Solomon on the need to rethink and reform curricula. Ballantine, for instance, had called for attention to be given to popular culture, especially black culture, pointing out that ‘ideological forces will make music departments lose their apolitical position and the myth of a unified music practice will dissipate’ (Reid 1982, 63).

Then ten years later and twenty years after Rörich’s article appeared, Ars Nova published a short piece by Antony Melck, taken from an address he had delivered at a Unisa graduation ceremony on 6 May 1993. Melck was then Vice-Principal (Finance) and later to become Vice-Chancellor and Rector of the university. (Melck 1993, 44-46). ‘As indicated by the name’, he wrote,

a university should ideally be comprehensive. By this is meant that as far as possible a university should represent all knowledge and provide an academic home for all subjects, schools of thought and view. In the spirit of this approach, a university should clearly also make provision for different cultures. … Discrimination in its most subtle form occurs when the impression is created that one community’s cultural treasures cannot be appreciated by another group … The conclusion that I come to is that the compartmentalisation of cultural works in this way cannot be justified at a university (Melck 1993, 45-46).

Two years later came Stanley Ridge’s opening address to the Committee of Heads of Music Departments in 1994 (1995, 108-109). Ridge, then Pro-vice-chancellor at University of the Western Cape, commented on what he identified as the two traditions in academic music and public life in South Africa. ‘One’, he said, ‘has dismissed indigenous music as primitive or “other” and asserted the primacy of the Western tradition … But there is another, more embracing tradition, going back to the eighteenth century’, he added, referring to Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon, the last Dutch commandant at the Cape. Gordon’s journeys to the interior of the country brought him into contact with some of the indigenous peoples. Ridge notes the mutual appreciation of musics during these trips and adds: ‘That tradition must be recovered. It is also part of our heritage’.

Rumblings in the Musicological World: What is Musicology?

Despite these sporadic warnings of imbalance and necessary transformation, the statistics given in Figs. 1a and 1b do not reflect any notable shift in trends within the twenty-five years from the journal’s inception to at least the mid-1990s – significantly perhaps, the time when South Africa achieved full democracy as a country. So how might we evaluate this data? What do they tell us about the kinds of research that were published during the thirty-five years of Ars Nova? What trends or biases might they reveal? And how do we account for the vast preponderance of topics dealing with Western art music in general in a scholarly publication originating in the southern part of Africa and published by an institution of higher education named University of South Africa? There are several strands which seem to me to be pertinent.

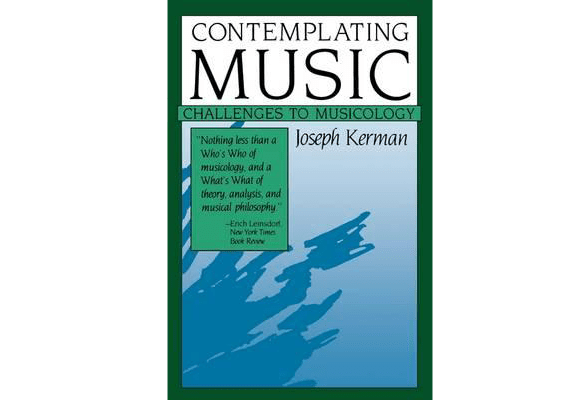

Joseph Kerman had already sounded an eloquent warning in 1985 against too narrow a view of music research in the international world of musicology with his book Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology (published in the UK as Musicology). As Nicholas Cook points out (1998, 95):

Musicologists and music theorists see ethnomusicology as the study of the music they don’t study; ethnomusicologists see it as the study of all music in terms of its social and cultural context, embracing production, reception, and signification. (Not surprisingly, then, the study of popular music entered ethnomusicology well before it reached either musicology or music theory.)

Soon several initiatives were under way in the UK, USA and elsewhere, particularly in the realms of popular music studies, music sociology, gender studies and other influences deriving from the discovery of cultural theory by musicologists. ‘Centuries from now,’ comments Kyle Gann (2000, 24), ‘the years 1980 to 1985 may well appear one of the most significant watersheds in the history of music’. The editors of Ars Nova, however, appear to have taken no notice – assuming they were even aware of Kerman’s book.

We have already noted Ridge’s remarks about the dismissal, still prevalent in the early 1990s, of supposedly primitive indigenous music in favour of Western traditions in research preferences. It’s fair to admit that prior to the mid-1980s or so, musicology was understood around the world as generally dealing with Western art music, while ethnomusicology was the ghetto to which the study of all other musics were relegated. Popular music studies had begun to emerge, but they remained under the umbrella of ethnomusicology which for a long time was always the musicology of the other. Yet for John Blacking (1987, 3), to cite one example of several notable dissenting voices, ethnomusicology was ‘not simply comparative musicology, in which exotic musical systems are analysed in relation to the parameters of the European tonal system … It is rather an approach to understanding all musics and music-making in the context of performance and of the ideas and skills that composers, performers and listeners bring to what they define as musical situations’.

Thus it was that Cook caused a stir some years later in 2008 by writing a chapter titled ‘We Are All (Ethno)musicologists Now’ for Henry Stobart’s The New (Ethno)usicologies, while Wim van der Meer had earlier proposed what he calls ‘hybrid musicology’ to encompass all music research. His motive can be summarized in his own words: ‘… [I]t seems to me that an independent discipline of ethnomusicology has no place in the third millennium … the very idea of ethnomusicology is a remnant of colonialism’ (2005, 63).[1] [1] For recent developments on the controversies surrounding the topic, see Stephen Amico, 2020. Though few might want to dispute that view today, Blacking’s statement was still radical enough in 1987 to warrant emphasis. But as early as 1972 J.H. Kwabena Nketia (1972, 283) had noted the ‘varying forms of acculturation in Africa’ from Islamic, south-east Asian and European sources, and urged the study of acculturation in music as being ‘of particular theoretical and practical interest’.

Editorial predilections

Undoubtedly the most important single guiding hand behind the editorial stance and mindset of Ars Nova was the person of Bernard S. van der Linde. Departmental head from 1968 until the end of 1990, Van der Linde held the reins of Ars Nova through most of its existence, as chief editor or co-editor from 1980 until his retirement in 1995. Given his tendency towards a domineering management style, we may reasonably assume that his guiding hand lay firmly on the selection and vetting of most articles even when not editor. It’s a matter of some significance that except for the final couple of years of publication before its demise in 2003 when application was made for Ars Nova to become an accredited journal with the National Research Foundation, no formal peer-reviewing of any kind ever took place; the editors had an entirely free hand in selecting material for publication with little outside monitoring of the contents.

As a master’s student at Wits in the late 1950s, Van der Linde had become infatuated with a system of harmonic analysis derived from that of his mentor Friedrich Hartmann who spent twenty-two years in South Africa from 1939 to 1961 as an exile from Austria, first as head of music at Rhodes and then at Wits. On Hartmann’s recommendation, Van der Linde proceeded to Vienna University where he completed his PhD on ‘Die unorthographische Notation in Beethovens Sonaten’ under Erich Schenk, drawing heavily on Hartmann’s harmonic theory of a ‘fully chromaticized scale’ to substantiate his contention that Beethoven – to put it bluntly – had not always known how to spell his chords correctly which were therefore sometimes unorthographic, and a stumbling-block to analysis. In his appreciation of Hartmann following his mentor’s death in January 1972, Van der Linde (4/1, 12-13) describes him as ‘my respected friend and teacher, Fritz Hartmann’, and records his pride at having been regarded by him as his ‘spiritual son’.

Hartmann, it seems, spent much of his life refining his Harmonielehre, originally published in 1934 by Universal Edition, which expanded his theory of Western harmony. Lavishing extravagant praise on its supposed virtues, Van der Linde assessed the manuscript as ‘a highlight of Western culture’ in a breathtaking panegyric that borders on hagiolatry (4/1, 14-15):

For me there can be no doubt that this comprehensive harmony treatise will come to be considered the most important of our century …

[T]his deep-going study … allows even the most experienced composer to discover and employ chords and chord progressions not conceived before …

This book will become indispensable to any representative library of the Western world and no serious music student, composer, journalist or musicologist will afford to ignore this highlight of Western culture.

Well, musicology has survived and harmonic analysis has moved on. Virtually a half century has passed since Van der Linde’s bold prediction in 1972 and still the manuscript remains unpublished, let alone attracting scholarly attention. While there may be some residual interest in the treatise as an historical document – such as has been shown in the Lost Composers and Theorists Project at the University of North Texas – its value as a handbook for composers and analysts today is precisely nil.[2] The jury remains out on the extent to which Hartmann may or may not have come to South Africa in the late 1930s under fascist pretences and been ‘an apartheid zealot or an unrepentant opportunist’ rather than a refugee from Nazi Austria; this is likely to remain an open question for a long time – see, for example, Michael Haas (2013). Erich Schenk’s history is both more sinister and more fully documented. He was an active if fairly ineffectual member of the Nazi party who in 1957 became Rector of Vienna University, having been head of the Musicology Institute at the university for many years, a post from which he retired in 1971. A particularly distasteful episode in Schenk’s biography is his role in the expropriation of Guido Adler’s private library by the Nazis after his death in 1941. The library was placed under the protection of a Nazi-approved lawyer, Richard Heiserer, who blocked the plan of Adler’s daughter Melanie to sell the collection intact following her father’s death in 1941 to a public archive in Munich. For years Schenk was deceptive about the library, even in the article he wrote about himself for Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Vol. 11, 1963). In the meantime, Melanie had been sent to Minsk for extermination in 1942. In 1957 Schenk became Rector of the University of Vienna. It was not until 2000, when a manuscript of the song ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ (I am lost to the world) composed by Gustav Mahler in 1901 and part of Adler’s library was to be auctioned at Sotheby’s in Vienna, that the matter of the ‘Schenk-Adler library’ was examined more closely. See Lebrecht 2004; Potter 1998; Sakabe 2004;

Nonetheless, the impact of Hartmann’s thinking on the direction of much Master’s and doctoral research at Unisa from the 1970s to the early 90s (almost all of it at Van der Linde’s hand) was profound. It accounts for a high proportion of the articles and reports published in Ars Nova up to the mid-1990s, not to mention protracted exchanges on the Hartmann theory between Van der Linde and Henk Temmingh that both amused and exasperated those attending local musicological congresses in the late 1970s.[3] Van der Linde published an article ‘In defence of F.H. Hartmann’s fully chromaticised scales’ in Vol. 9 (1977: 16-24). It gave rise to a challenge by Temmingh in a paper delivered at the Fifth Musicological Congress of the Committee of Heads of Music Departments (CHUM) in 1978, followed by Van der Linde’s rebuttal at the Sixth Musicological Congress the following year. A year later Temmingh took things further at the 1980 congress of the newly-formed South African Musicological Society with his paper ‘Enkele beskouinge oor tonaliteit na aanleiding van Schönberg se Opus 11, nr. 1’ (‘Some reflections on tonality with reference to Schönberg’s Opus 11, no. 1’). At the outset he referred specifically to his paper of 1978 and Van der Linde’s response a year later, and stated that he intended discussing only Hartmann’s concept of tonality – which he considered unsuited to analysing music generally accepted to be atonal – rather than his chord classification system. This triptych of papers occupied the bulk of Vol. 12 (1980: 11-19, 20-26 and 27-42). A further contribution on the subject by Van der Linde, ‘In defence of F H Hartmann’s fully chromaticised scales’, appeared in Vol. 9 (1977, 16-24). The analysis of harmonic phenomena, considered as isolated elements in a musical composition, together with a dogged fixation on ‘the music itself’, ‘divorced’ as Taruskin (2010, 4) puts it ‘from the social world, subject only to internally motivated stylistic change’, is today little more than an ideological dinosaur and a relic of positivist thinking. Within a year or so of Van der Linde’s retirement from UNISA the system, which had been the foundation of analytical studies and much of the postgraduate research in the department for over two decades, fell into disuse.

Van der Linde was the kind of musicologist who seemed to believe that most ‘real’ music research was bound to embrace an investigation into harmony at least in part and in the most positivist way, devoid of context and disregarding both societal and cultural influences. Edward Said (1994, 50) cites a parallel from literary studies when he notes that its academic tradition from before World War Two until the early 1970s ‘the main tradition of comparative-literature studies was heavily dominated by a style of scholarship that has now almost disappeared. The main feature of this older style was that it was scholarship principally, and not what we have come to call criticism’.

In many ways, though, was he not simply a man of his time like the rest of us? If we can acknowledge that he had been inducted in Johannesburg and Vienna into a type of scholarship that had become less fashionable as the twentieth century drew to a close and research methodologies changed, we begin to understand his predilections for supervising research topics involving harmonic analysis to postgraduate students (as in my own 1970s MMus thesis, written under his supervision). It also goes some way to explaining his particular interests that profoundly influenced the contents of Ars Nova articles into the 1990s when he relinquished control of the journal. Here it might be worth recalling anecdotally that when Wilfrid Mellers, the British composer, critic and academic, visited Unisa in the mid-1970s to give a concert with British soprano Poppy Holden he also gave a public lecture in the evening hosted by the Department of Musicology. Van der Linde pointedly passed up the opportunity to attend both the recital and the lecture, delegating the role of introducing and chairing the occasion to a senior lecturer: his decision evoked considerable comment behind his back among departmental members. Mellers’ love of Couperin, Bach and Beethoven along with folk music and jazz, and his kind of musicology – for all its international acclaim at the time – was beyond Van der Linde’s ken: it wasn’t primarily about harmonic analysis. (On a personal note: it was during Mellers’ lecture that evening that I first heard about Dollar Brand, later known as Abdullah Ibrahim.)

A Limited Understanding of South African Music

A suitably prominent element in the roster of published articles in Ars Nova is South African music. But what exactly constitutes South African music? The question is nowhere addressed explicitly in Ars Nova, but based on a survey of the titles of the many articles published on aspects of South African music in Ars Nova, it’s clear there’s an implicit assumption that, with few exceptions, only Western art music warranted academic attention.[4] Rare notable exceptions are two articles on ‘Coloured’ folk music by Frikkie Strydom and Jon Drury in Vol. 17 (1985, 22-50). On the other hand no articles deal with jazz in South Africa. So, for example, we find articles on the symphony in South Africa (‘Die simfonie in Suid-Afrika tot en met 1989: ’n oorsig’), the symphonic poem and tone poem in South Africa, the keyboard concertos of South African composers [1960-1980], South African chamber music (‘Suid-Afrikaanse kamermusiek: ’n historiese oorsig’), recorder playing in South Africa, the contribution of Hendrik Visscher as an early South African composer (‘Die bydrae van Hendrik Visscher (1865-1928) as vroeë komponis van Suid-Afrika’), and a brief biography and appreciation of the violin builder J.J. van de Geest, all of historical interest but hardly representative of music-making in the country as a whole.[5]Despite their historical significance and artistic worth in terms of the history of Western art music in South Africa, these works have never become part of regular concert programming in the country.

Nevertheless, valuable research on both local and international topics was also published in articles on such matters – for example – as a catalogue of the Grey Collection of medieval manuscripts in the South African Library (Cape Town), the editing and publishing of music, module transfer in the Gradualia of William Byrd, Manuel de Falla’s Siete canciones populares Españolas of 1914, and Lutosławski’s technique of ‘limited aleatorism’.However, that there existed a vast repertoire of frequently-performed choral music by black composers in addition to many other musical traditions thriving among the country’s preponderant black population was seemingly a matter of little consequence: for the most part it fell outside the ambit of ‘musicology’. The few exceptions include contributions on the Old Mutual/Telkom National Choir Festival, an interview with composer and educator S.J. Khosa, and a study of Griqua choral music.

If, as Walter Benjamin (1955) pointed out, we can accept that ‘there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’, then

the contents of Ars Nova cannot help but reveal both the genuinely civilizing and the callously barbarous tendencies of the sophisticated culture in which it was embedded.

The almost total disregard of South African indigenous and popular music (and indeed, of popular music from anywhere) reinforces what Perés-Torres (1994, 167) has called ‘the nostalgia for tradition – rather than the critical examination of what tradition means’. This nostalgia, he adds, ‘marks a neoconservative agenda that seeks to impose social control based on words like “morality” and “justice” and “quality”’. And as Said remarks, in discussing T.S. Eliot’s notion of tradition in the work of the poet, ‘how we formulate or represent the past shapes our understanding and views of the present’ (Said 1994, 2).

Apartheid, Ideological Mythology, and Imagined Culture

Why an ‘imagined culture’ and why the arguably pathetic attempts to preserve it within academic discourse? Western art music in South Africa was after all alive if not entirely well for most of the time Ars Nova existed, even if it was altogether unrepresentative of musical activity in the country as a whole. To help answer this question we need to broaden the scope of our enquiry. Charles Hamm’s insightful article ‘Separate Development, Radio Bantu and Music’ quotes Roland Barthes as stating that ‘myth consists in overturning culture into nature or, at least, the social and cultural, the ideological, the historical into “the natural”. Under mythical inversion the quite contingent foundations of the utterance become Common Sense, Right Reason, the Norm, General Opinion’ (Barthes 1972, 165, quoted in Hamm 1991, 152). While it’s unnecessary to detail here the many insidious ways in which the apartheid policies of the South African Nationalist government affected life in the country over a period of almost half a century from 1948, it is instructive to note that ‘such institutions as the educational system, the de facto state religion and the state controlled media were given the task of bringing about general acceptance of this ideologically based mythology, by persuading the entire population that this was the “way things were”, according to nature, history and common sense’ (Charles Mann 1991, 153). Thus it was that the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) had fallen under the control of the Nationalist government and as Hinch puts it, its resources used ‘to portray South Africa as a Western power with the same cultural heritage as the countries of Europe’ (John Hinch 2004, 73).

Hinch notes the SABC’s statement of 1962 outlining its policies that read in part:

Radio South Africa should, by means of positive contributions in its own sphere, promote the survival and bounteous heritage of the White people of the Republic of South Africa while at the same time encouraging the development and self-realization of the non-white population groups in their own spheres.

So it was that Malcolm Sargent had been brought out to South Africa to conduct the SABC Symphony Orchestra in the world premiere of William Walton’s Johannesburg Festival Overture in September 1956 at the Johannesburg Festival celebration of the city’s 70th anniversary (Jeffrey Brukman 2018, 263), while 1958 saw the world premiere of the radio opera Asterion, commissioned from Henk Badings by Anton Hartman who was then head of music at the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) (Walton 2004, 69).[6] Chris Walton (2004) has shown how the enthusiasm of the apartheid state and civic authorities to signal its alignment with the West and its anti-Communist stance by wooing prominent figures in the arts – notably music – to visit the country, thereby virtue signalling its policy of preserving ‘Western civilization and values’. Badings returned to Johannesburg in 1968 to introduce the marvels of electronic music to enthusiastic (white) composers at an electronic music studio set up at the SABC’s headquarters in Commissioner Street, Johannesburg.

Meanwhile, and again at the behest of Anton Hartman and the SABC, Stravinsky had visited the country in 1962 to conduct his Symphony of Psalms and a shortened version of his Petrushka suite in Johannesburg, though his visit was marked (or marred, depending on your viewpoint) by his refusal to perform in front of a segregated audience (John Hinch 2004). Some years later none other than the great high wizard of the avant-garde, Karlheinz Stockhausen, deployed a dazzling mixture of electronic alchemy and cosmic philosophy before mainly admiring but bewildered audiences in Johannesburg and Pretoria during his visit to the country in 1971.[7] In a paper delivered at the University of Bristol, William Fourie (2018, 4-5) quotes my own description of the event and the audience’s reaction, which I sent to him in a private communication.

Notwithstanding the spectre of apartheid, Unisa was relatively liberal in the 1960s, the 70s and later. As Rector from 1956 to 1972, Samuel Pauw won a momentously significant battle during the 1960s to retain the university’s character as a place of higher education for all the citizens of South Africa – this despite being Deputy Chair of the Broederbond (but probably the result of holding considerable power in that position).

In the early 1960s, the Department of National Education lobbied to relocate Unisa to Johannesburg. The envisaged move would make Unisa an exclusively Afrikaans-medium university, and correspondence tuition for black students would be terminated, eradicating its bilingual character and surprisingly multiracial student body. Pauw’s stubborn resistance saved Unisa; Cabinet eventually rejected the plan. Pauw is credited with transforming Unisa into ‘a national university of the first rank’ and aligning Unisa with the distance learning technology of the day … (Unisa online 2021).

Not only was its editorial policy so out of touch with the rich diversity of music within South Africa, Ars Nova remained virtually untouched by the changing world of international musicology. Largely unruffled by the concerns of the ‘New Musicology’ that emerged so powerfully in the late 1980s and early 90s, the journal gradually, if reluctantly, began to adopt a more open publishing policy – and only once it had become ideologically and politically correct following both the democratization of South Africa in the early 1990s and the introduction of course modules in the department dealing with world musics and jazz.

Hence the occasional appearance at this time of articles such as those dealing with aspects of jazz (Vol. 26, 1994), the Soweto String Quartet and their album Zebra Crossing (Vol. 29, 1997), the Simunye collaboration between I Fagiolini and the SDASA Chorale (Vol. 30, 1998), music performance and AIDS in South Africa (Vols. 33 and 34, 2001/2002, and a review of the PASMAE benefit launch concert at UCT (Vol. 35, 2003). But even these sporadic instances represent only an infinitesimal proportion of all the various articles and reports that appeared.

That the real story of South African music as ‘one of dialogue with imported forms, and varying degrees of hybridisation over the years’ (SouthAfrica.info webpage 2012) was virtually disregarded in the greater bulk of the research selected for publication in Ars Nova – whether through ignorance, indifference, or ideological bias – is a blight on the journal’s history. Under the patronage of a venerable national institution bearing the country’s name – the alma mater of many noteworthy figures in South Africa’s history, not least that of Nelson Mandela, as well as the first institution of higher learning in the country to award the BMus degree to a black musician, the composer Michael Moerane – Ars Nova largely maintained an attitude of racial and cultural condescension and prejudice towards a substantial part of the ‘real’ story of music making in South Africa.

By ignoring the full range of musics practised in South Africa, Ars Nova perpetrated the notion of a South African musical culture that can only be defined as an imaginary one, a strategy of survival for a white civilization at the southern tip of Africa that had never really existed.

As Homi Bhabha (1994, 247) explains:

Culture as a strategy of survival is both transnational and translational. It is transnational because contemporary postcolonial discourses are rooted in specific histories of cultural displacement, whether they are the ‘voyage out’ of the civilizing mission … or the traffic of economic and political refugees within and outside the Third World. Culture is translational because such spatial histories of displacement … make the question of how culture signifies, or what is signified by culture, a rather complex issue.

Despite all the biases and lacunae of the journal, there is no question that with 35 volumes spanning a thirty-four period covering a time of significant growth in South Africa’s music research, Ars Nova remains a valuable record of some of the musicological activity conducted in the country during the last quarter-century of the apartheid era and the first historic decade of a new democratic dispensation.[8] Ars Nova was superseded in 2004 by Muziki: Journal of Music Research in Africa, launched by Unisa in collaboration with Chris Walton who was at the time head of music at Pretoria University, and published jointly by Unisa Press and the British academic publishers Taylor & Francis. Significantly, the journal policy outlined on the inside cover in the first number of Muziki states in part: ‘The journal wishes to establish a unified African voice for African music research. Through its juxtaposition of the historical and the theoretical, the indigenous, the popular and the “Western”, it intends to reflect the diversity of African musics and the research that they inspire’.

In 2008 the entire contents of Ars Nova were scanned onto the Taylor and Francis website (tandfonline.com) where they are available for further consultation and analysis, along with the contents of its successor, Muziki.

For their valuable historiographical contributions to South African music history, for what they tell us and what they do not tell us, for their signification of what Bhabha (1994, 247) calls ‘embedded myths’ and the light they shed on the imagined culture I suggest they imply, the contents of Ars Nova remain a valuable and significant repository of data about music research in this country during the final decades of the twentieth century.

Perhaps the final word should be left to American musician and popular music historian Bill Malone, author of Country Music USA: A Fifty-Year History, 1968. Speaking in the documentary Country Music, made by Ken Burns for PBS and aired in the USA in September 2019, he observes (cited by Alex Abramovich 2020, 37):

Country music is full of songs about little old log cabins that people had never lived in, the old country church that people have never attended. But it spoke for a lot of people who were being forgotten – or felt they were being forgotten. Country music’s staple, above all, is nostalgia. Just a harkening back to the old way of life, whether real or imagined.

This article is a revision and extension of a paper read at the annual SASRIM conference, Tshwane University of Technology (Pretoria), 19-21 July 2012.

| 1. | ↑ | [1] For recent developments on the controversies surrounding the topic, see Stephen Amico, 2020. |

| 2. | ↑ | The jury remains out on the extent to which Hartmann may or may not have come to South Africa in the late 1930s under fascist pretences and been ‘an apartheid zealot or an unrepentant opportunist’ rather than a refugee from Nazi Austria; this is likely to remain an open question for a long time – see, for example, Michael Haas (2013). Erich Schenk’s history is both more sinister and more fully documented. He was an active if fairly ineffectual member of the Nazi party who in 1957 became Rector of Vienna University, having been head of the Musicology Institute at the university for many years, a post from which he retired in 1971. A particularly distasteful episode in Schenk’s biography is his role in the expropriation of Guido Adler’s private library by the Nazis after his death in 1941. The library was placed under the protection of a Nazi-approved lawyer, Richard Heiserer, who blocked the plan of Adler’s daughter Melanie to sell the collection intact following her father’s death in 1941 to a public archive in Munich. For years Schenk was deceptive about the library, even in the article he wrote about himself for Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Vol. 11, 1963). In the meantime, Melanie had been sent to Minsk for extermination in 1942. In 1957 Schenk became Rector of the University of Vienna. It was not until 2000, when a manuscript of the song ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ (I am lost to the world) composed by Gustav Mahler in 1901 and part of Adler’s library was to be auctioned at Sotheby’s in Vienna, that the matter of the ‘Schenk-Adler library’ was examined more closely. See Lebrecht 2004; Potter 1998; Sakabe 2004; |

| 3. | ↑ | Van der Linde published an article ‘In defence of F.H. Hartmann’s fully chromaticised scales’ in Vol. 9 (1977: 16-24). It gave rise to a challenge by Temmingh in a paper delivered at the Fifth Musicological Congress of the Committee of Heads of Music Departments (CHUM) in 1978, followed by Van der Linde’s rebuttal at the Sixth Musicological Congress the following year. A year later Temmingh took things further at the 1980 congress of the newly-formed South African Musicological Society with his paper ‘Enkele beskouinge oor tonaliteit na aanleiding van Schönberg se Opus 11, nr. 1’ (‘Some reflections on tonality with reference to Schönberg’s Opus 11, no. 1’). At the outset he referred specifically to his paper of 1978 and Van der Linde’s response a year later, and stated that he intended discussing only Hartmann’s concept of tonality – which he considered unsuited to analysing music generally accepted to be atonal – rather than his chord classification system. This triptych of papers occupied the bulk of Vol. 12 (1980: 11-19, 20-26 and 27-42). |

| 4. | ↑ | Rare notable exceptions are two articles on ‘Coloured’ folk music by Frikkie Strydom and Jon Drury in Vol. 17 (1985, 22-50). On the other hand no articles deal with jazz in South Africa. |

| 5. | ↑ | Despite their historical significance and artistic worth in terms of the history of Western art music in South Africa, these works have never become part of regular concert programming in the country. |

| 6. | ↑ | Chris Walton (2004) has shown how the enthusiasm of the apartheid state and civic authorities to signal its alignment with the West and its anti-Communist stance by wooing prominent figures in the arts – notably music – to visit the country, thereby virtue signalling its policy of preserving ‘Western civilization and values’. |

| 7. | ↑ | In a paper delivered at the University of Bristol, William Fourie (2018, 4-5) quotes my own description of the event and the audience’s reaction, which I sent to him in a private communication. |

| 8. | ↑ | Ars Nova was superseded in 2004 by Muziki: Journal of Music Research in Africa, launched by Unisa in collaboration with Chris Walton who was at the time head of music at Pretoria University, and published jointly by Unisa Press and the British academic publishers Taylor & Francis. Significantly, the journal policy outlined on the inside cover in the first number of Muziki states in part: ‘The journal wishes to establish a unified African voice for African music research. Through its juxtaposition of the historical and the theoretical, the indigenous, the popular and the “Western”, it intends to reflect the diversity of African musics and the research that they inspire’.

In 2008 the entire contents of Ars Nova were scanned onto the Taylor and Francis website (tandfonline.com) where they are available for further consultation and analysis, along with the contents of its successor, Muziki. |