Throughout the entirety of the idiomatic spectrum of musical expression courses a golden drone. This is the spiritual spine of all life manifested through the power of the unimpeded flow of sound; the exquisite vibration that unifies all entities in existence, whether tangible or intangible. The nesting place of this sound is silence. In the infinite depths of silence lives the potential for this oscillation. The chosen musician, who cannot be silenced, knows without knowing how to herd this sound into the arena of lived reality. This perspicacity reveals to them early in their emergence that they are bestowed with the gift of being a conduit for the drone to permeate all life.

I am fortunate to have known two such musicians in my blessed life. I was accompanied by one when I went into exile from South Africa and met the other who was already in exile when we arrived in Europe. I left South Africa with the phenomenally gifted multi-instrumentalist Bheki Mseleku in 1980. My life as an anti-apartheid activist in the Steve Biko-led Black Consciousness Movement had become unsustainable. I had already been creatively associated with supporting Bheki’s development as one of the most inspiring young jazz musicians making waves in our country.

When I decided to escape with my then girlfriend Mary Edwards, whose little upright piano Bheki would sometimes play non-stop for three full days, at the last minute the master musician opted to join us. He told me that he could not see a life without me in our mournfully beloved country.

In Munich we attended a concert by our friend and fellow South African Abdullah Ibrahim (formerly Dollar Brand). At the end of the gig we went backstage to catch up with the legendary pianist, to whom I gave a poem I had written for him before leaving the country. We were excited to see each other. On hearing about Bheki’s aspiration to gain international exposure as a musician, Abdullah unhesitatingly recommended that he seek asylum in Sweden. His confidence in the viability of this idea was supported by the fact that the country had a thriving jazz scene with other exiled South African musicians at its core, and which attracted renowned American jazz musicians such as trumpeter Don Cherry and saxophonist Ornette Coleman.

Double bassist Johnny Dyani went into exile with the radical jazz sextet Blue Notes in 1964 and drummer Gilbert Matthews, who had already experienced life outside South Africa, moved to Sweden in 1979. These were two outstanding South African musicians whose boundless inspirational energy sent ripples across Europe from their creative hub in Stockholm.

Bheki knew Gilbert from their time as co-founders of the pioneering band Spirits Rejoice in South Africa. Though he was meeting Johnny for the first time, their mastery had long been known to each other through the apartheid evisceration of the wholeness of our soul as a people of the subterranean drone. So, in simple terms, Dyani and Mseleku were reconnecting at the deeper partials of their umbilical sound vibrations – to recalibrate their shared soul intonation away from the womb of their memory.

They were bound to reconnect like confluences of the same baptismal river of healing.

Their flow nourished the lives of their ardent audiences and students across Scandinavia and the Netherlands. Their tidal waters spilt over to the rest of Europe and the United Kingdom. If there were ever musicians who Africanised historically European instruments, Bheki Mseleku and Johnny Dyani led this revolution with the audacity of fearless innovators.

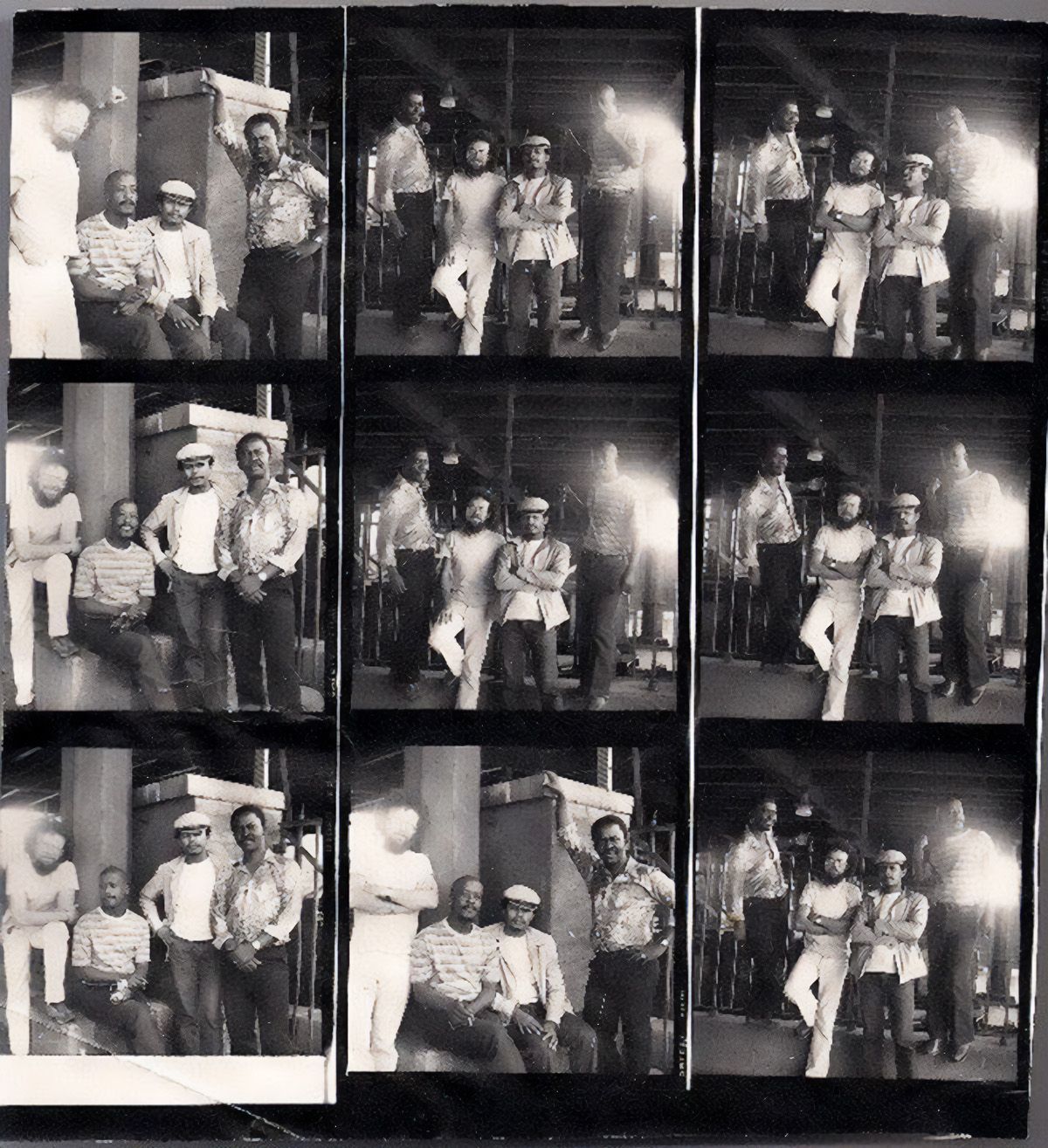

imbizo

eugene skeef 1980s

(for johnny dyani – bassist)

we make music

now

from the tendons

of a slain warrior –

lullaby

for the pain

of a gutted

love…

Dyani, with his sinewy frame, was not at all intimidated by the imposing double bass rooted in sixteenth century Italy. If you were to close your eyes as he danced close up with the finely sculpted body of the beautiful instrument, you could be certain that you were hearing the unequivocal plangency of a Moroccan gimbri, Malian ngoni or the Mandé warrior king’s bolon. And, like the warrior he was, his singing voice would singe the sound of the double bass and bestow it with the inseparable quality of a fire whose ignition resides in the memory of the undammed pain of a nation’s unrequited love.

benediction

eugene skeef 6 December 2016

(for bheki mseleku)

there was once a man

whose inner ear

was an atrium

into the cathedral

of the soul

Mseleku brought out the African mbira housed in the cathedral of the Steinway grand piano for airing. Not having owned a personal piano until his record deal with Verve in 1994, in Stockholm he was granted special access to Fasching Jazz Club by the management so that he could practice on their resident Steinway overnight until they needed to open to the public the next day. These all-night sessions organically evolved into an informal academy, whereby the cream of local jazz and European classical musicians would drop by to imbibe the harmonic and improvisational wisdom of the South African genius. Throughout these assemblies around the piano Bheki would hardly speak, with his handsome head tilted back and his heavenward eyes closed. The intense vibration of his playing would serve also as an agent of healing for whoever was in the room. One man in particular felt this vibration strongly. He occupied the fringes of Swedish society because his behaviour was considered to be off-centre; but when he was in the presence of Bheki’s non-stop improvisations, he was as centred as the sun that danced on the other side of the world from him. He would be transfixed by the piano, leaning in to listen more acutely to the vibrating strings. Then Bheki would get up from his stool and keep his foot on the sustain pedal while playing intervallic extemporisations on his tenor sax. This made the piano strings vibrate even more emphatically in sympathetic resonance with the invisible orchestration of harmonics dancing to the density of his improvising. The realigned man would be so moved by the singing strings that he would toss the saxophone mouthpiece cap onto them and be inspired by its percussive bobbing and begin to dance round the Steinway.

It was not long before Dyani joined Bheki and became a part of the energy that flowed from these nightly sessions, and, whenever and wherever the forces of fortune subsequently brought them together, those in the room were blessed by the unfolding of a sacred ritual ceremony of the most profound African variety. Their humour, conviviality and unparalleled musicianship constituted a spiritual pollen that would spread through the space with an efficiency of transposition associated more poetically with the vibration of the amnion of the cosmos, but through the innermost membrane of their audience’s soul.

They started gigging together in various combinations with local Swedish musicians; but the Johnny Dyani Quartet, with Bheki on piano, Gilbert Matthews on drums, and Sweden’s own Ed Epstein on saxophones, is the memorable unit that brought them to the pinnacle of their synergy. Ed once told me that “just being around Bheki was a charged experience. Playing with him was always deep, as it was with Johnny as well.”

I have my own memories of Bheki’s depth and breadth of musicality. He had the unique capacity to make his music stretch beyond the understood idiomatic scope of possibilities. He could play with anyone and infuse their music with a rigorous freshness and relaxed vigour that was unbelievable. This is what he succeeded to do when he came together with Johnny, whose experience of harmonic exploration had been different with The Blue Notes. In Bheki, Johnny found a kindred spirit for whom the formally perceived limits of their instruments meant nothing but a boundary to actively transgress with the liberating tools of their inspired genius.

Another memory that comes to me as I ponder the profundity of the synergy of their mastery is from the late 1980s in London. John Lunn, an English friend, who was a bassist with the London Sinfonietta, approached me at the end of a solo concert by Bheki at the Royal Festival Hall. He told me that my compatriot exuded one of the most appealingly eloquent left hands in the world of jazz piano. He could not get over the beautifully heavy melodic quality of the chordal grounding of his flourishing improvisations. The spirit of Dyani, also a captivating pianist in his own right, was ever present in the lower register of Mseleku’s African pianism.

I had the honour of clasping the hands of both these brothers in my time of knowing them. They were soft. But this softness was deceptive. Their hands had a tenderness to them that sheathed a great power that came out when they expressed the deeply embedded spirit of music. I witnessed both musicians bleed when they played their instruments.

Mary Maria Parks, partner of the great avant-garde American saxophonist, singer and composer Albert Ayler, is credited with the phrase

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe

from Ayler’s 1969 album by the same title. Music is undoubtedly the greatest force for self-healing. Dyani and Mseleku bled because of the risen tide of their self-healing. And through tapping into the root of healing themselves they were guided onto the route to healing their audience. The inevitability of this truth of spiritual permeability was borne out in every performance they gave together as they selflessly let themselves dissolve into the cascade of inundating inspiration.

Dyani and Mseleku used to play long rambling solos because they were responding to the spiritual call. A call to prayer for the blessings of eternal flow, which is another core purpose and motivating force of music.

In answer to the call they would spread the spores of their musical inspiration to circle the audience to frame them in the original African homestead, then cycle the repetitious chord sequence so as to bear their souls through the energy dome and return them to the comforting notion of home after every displacement of the harmony… This is groove!

Africa gave the concept of groove to the world through its ripples across tempered oceanic vibrations that defied captivity. Groove is the essence of freedom in that the truly gifted improviser seeks always to find the way out of the tight confinement of repetitive cycles – as echoed in the freedom of nature.

Bheki and Johnny were truly gifted improvisers who could groove until the proverbial cows came home. Their instinctive home-grown sense of rhythm was their rudder that guided them to the greener pastures that were locked in the enclosure of life under apartheid.

The free fields of their roaming dreams pulsed inside their bosoms. They learned from the children’s games they played on the dusty streets of Duncan Village, in East London (eMonti), and Lamontville, in Durban, that the repetitive groove would always bring them back to where they started – home. The journey around the containing block would always serve the purpose of reinforcing the rootedness of their identity; so that no matter how far harmonically they may wander in their desire to be free from the constraints of their limitations, they would invariably always land back at the home of their original sustenance.

I recently chanced to listen back to Bheki playing tenor sax in the Chris McGregor Quartet at the Bracknell Jazz Festival in the United Kingdom in 1996. I could hear the harmonic mastery of John Coltrane flow forth in his solos with the unhindered ease of a Savannah river during the rainy season. The spirit of the great American improviser courses through the mouthpiece originally used in the seminal recording of his masterpiece A Love Supreme. Bheki was given this mouthpiece by Coltrane’s wife Alice Coltrane when they met at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1977. The majesty of the South African’s tone on the horn affords him the expressive latitude to emulate his naturally fibrous singing voice that infuses his piano melodies with the timbre of deep spiritual African chanting. When Bheki transposes this technique of sonic striation to the Steinway grand piano, it is as if he is making sure that not a single oscillation of sound imprisoned in the Western tempered chromatic tuning system escapes his influence as a conduit of the healing vibrations from beyond the enclosed structure of the instrument.

In the reknotted string of our cultural traditions, Johnny’s middle name Mbizo translates as a gathering or convocation summoned by the chief.

He embodied the wisdom of ages in his creative disposition. I remember him speaking with me about his consciousness of this responsibility enshrined in him by the elders in his community back home. He preserved and promoted this through his performances.

Similarly, Bheki proudly embraced the adulations of the Mseleku clan, which pertain to water. He openly personified through his musical expression the fountain from which we all readily drank. He funnelled the rain of stars from the heavens to quench our parched yearning for our appropriated praises.

The American poet Langston Hughes, in his poem Harlem, asks: “What happens to a dream deferred?” To be without a dream is to be without a soul. Sometimes a people’s dream of freedom is not postponed, but transplanted, through the portal of the artist, for special delivery through the vibrations of the blood-stained strings of their hearts.

The jazz of Dyani and Mseleku is a highly cultivated art of liberation.

It offers a gateway into the world outside the pressing walls of containment, so that others in their community can let their souls fly through the porosity of their combined song, and experience the world beyond their truncated horizons.