ARYAN KAGANOF

Somebody Blew Up South Africa

When Dudu played we forgot that we were in exile. Forgot even that who “we” were was uneasily defined, amorphous. We were “compatriots” from a country that had indoctrinated us with a profound sense of our separateness. We had, from birth, always been separated from each other and this meant, ultimately, from ourselves. Paradoxically the separation from South Africa meant that we could finally meet each other – as exiles – and share bittersweet memories of the terrible place we called home. We hated it but we wanted, more than anything, to go back ekaya. We loved it but we wanted to change it, irrevocably. To change ourselves. To repair our separated selves. What we all had in common, regardless of hue, what we all shared – was an intense and unbearable nostalgia for a place that had never existed.

We lived in three distinct places. Firstly, the shadowy place of incessant and very futile nostalgia for where we came from. Secondly, the distant promise of a place where we were always going back to, one day, without any certainty that it would ever happen. And finally, groundingly, the drab grey reality of daily life in the place we were temporarily located – the country of our exile. This partitioning of the self disallowed us full participation in the everyday we were living through. But wherever it was, this wasn’t our home turf – like Howard the Duck, we were trapped in a world we had never made.

Exile robbed us of an ordinary life. Being unable to go back framed us in a highly self-conscious and always tragic mythopoeia. The nostalgia was, of course, a lie. Memory is always fiction. We invented home. We created a South Africa that had no basis in reality. No place could be that special. In fact the place we longed to go back to, that place we were all, to varying degrees, involved in fighting for, existed only in the music. With our eyes closed, listening intently, Dudu took us, his congregation, back home, back there. Back to a place that had never been and was never going to be. When Dudu played we forgot that he was in exile too. He invented South Africa. Concocted a sound that dematerialized the matter of separation that we had been given as fact and replaced it with a cacophonous, unruly, uncategorizable collection of dances and bellows, marches and whispers, stomps and chants; a black noise that haunted us into believing we were winners and that it was precisely this particular memory of home that we were collectively imagining right now, together, that made us different, made us special, made us somehow less abject in our not-at-homeness.

With his eyes closed, blowing concentratedly into the mouthpiece of that alto or soprano saxophone, Dudu summoned into being the warm spirit of an impossible home and shared it with us, his acolytes. In his passionately blowing presence we were made privy to an emancipation so incandescent that the merely political liberation of the struggle glowed like a 40 Watt bulb by comparison. It wasn’t a gig. It wasn’t a concert. It was a way of staying alive. Perhaps the only way.

I am 20 years old. It is two weeks before my 21st birthday. On the 9th of March I will officially come of age. But tonight, Saturday 23rd of February 1985 is my birthday present to myself. Tonight is the first time I will see Dudu Pukwana perform live. I have many vinyl records that feature Dudu’s alto and soprano playing. His solos on Hugh Masekela’s Home Is Where The Music Is are the reason that 1972 album remains Bra’ Hugh’s most profound recorded set. Dudu’s angular, elegaic alto playing can be heard to heartbreaking effect on Johnny Mbizo Dyani’s Witchdoctor’s Son recording of 1978 – most pertinently on the anthem Song For Biko.

Then of course there are the two brilliant records as a leader, Diamond Express and Flute Music, (both 1975), featuring sublime trumpet solos from the late Mongezi Feza. But it is Dudu’s scorched earth playing on the visceral hauntology of grief that is Blue Notes For Mongezi (1975) that has turned me into a disciple. To listen to this threnody of love for a fallen comrade is to understand how far into the soul recorded sound can travel; beyond art, beyond jazz, beyond any intellectual attempt to comprehend and thereby tame it – this sound exists not only to mourn and exorcize grief, but to return the Omega to the Alpha, to begin again after the end.

I have been listening to the Four Movements of the Blue Notes For Mongezi double lp every day for nearly a year since first discovering it at the Jazz Inn on the Vijzelgracht, Amsterdam. Tonight I will get to see Dudu play for the first time. I will climb onto my bicycle at 7pm and cycle from my Bos en Lommerweg apartment in Amsterdam West across town, braving the minus fifteen degrees Celsius freezing cold, through thick swirling snow all the way to the Piet Heinkade just East of the Red Light district to the home of jazz, the Bimhuis, where Dudu Pukwana’s band Zila will start performing at 8pm.

Who was Dudu Pukwana?

“…actually Dudu was the man who started the Blue Notes with Chris (McGregor). But Dudu was behind all that and Chris was, you know, there, but Dudu was the composer and Chris was kind of the arranger of Dudu’s songs but Dudu was the one. And Dudu was the one who taught Chris to play mbaqanga on the piano and showed him what it’s all about”. That’s according to Blue Notes bass player Johnny Mbizo Dyani in an interview I did with him in the offices of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement on the Lauriergracht in Amsterdam on the 23rd of December 1985.

Dudu was born on 18 July 1938 in Walmer Township, Port Elizabeth and his first instrument was piano but at the age of 18 he switched to alto sax after meeting tenor sax player Nick Moyake. His first group with pianist Chris McGregor was The Cape Town Five, alongside tenor player Cups Nkanuka, drummer Martin Mgijima and bassist Don Staegemann. Although the band won a prize at the Johannesburg Town Hall Jazz Festival they were never recorded.

Dudu’s earliest recorded solos can be heard on the 78rpm Meritone Big Beat release Size 10/ Allright Dudu produced by Gibson Kente in 1961. A fascinating syncretion of South African rhythmic fireworks overlaid with a hard bop sensibility that spells it out clearly – Dudu has absorbed Sonny Stitt’s absorption of Charlie Parker. Also recorded in 1961 and produced by theatre legend Kente for the Meritone Jazz Series are two Pukwana compositions One-Two-Three and Cape Town Dudu. A musicologist could write a PhD about exactly why this music is so infectious but as Johnny Dyani said,

“When you start to write about music you start lying.”

This music has to be heard, and it has to be heard while dancing. Dudu’s alto line is as much part of the rhythm it is cross-pollinating as it is part of the melody that it never quite decides to unveil. Impishly classy, joyous and utterly addictive.

Dudu’s next recording is probably the rarest, least known item in the South African jazz discography. Mr. Paljas was an African musical composed by Stanley Glasser, who was then a lecturer at the SA College of Music. Although all 16 tracks are Glasser compositions there is some spirited playing by among others, Hugh Masekela and Dennis Mpali (trumpets), Blythe Mbityana (trombone) and Cornelius Kumalo (baritone sax and clarinet). The outstanding solos however, all belong to Dudu, especially a searing one on Rock Lobster (no, it’s not the B52s tune!).

Dudu’s next recording date was on 8th September 1962 in the Grand Hall at Wits University as part of Gideon Nxumalo’s Jazz Fantasia. Composer and pianist Nxumalo wrote of Dudu:

“Split Soul has been dedicated to, and especially written for Dudu Pukwana. As was the case with Isintu, this piece has been written to accommodate the exponent’s particular style. Dudu has an aggressive deep sounding style and I reckon this particular number is just up his Street. It also starts off a ballad, goes up-town, then tapers right down to the original ballad.

The idea behind this piece was to portray Johannesburg in very early hours of the morning when all is quiet and all you hear is the occasional sound of the milkman or nightwatchman, or some musicians dragging their feet wearily homewards after a stint at a club or something”.

Gideon Nxumalo

In 1962 drummer Makaya Ntshoko, who had come to prominence as the anchor of Dollar Brand’s Jazz Epistles, formed his own group Jazz Giants which included Tete Mbambisa on piano as well as Dudu who won the first prize for Best Musician on Alto Sax at the October 1962 Castle Lager Jazz Festival. A compilation featuring all the different bands that took part in the festival was released by Gallo as Jazz 1962 and later re-released as Cold Castle National Festival Jazz 1962 on CD by Teal. An anonymous reviewer at the time wrote “Dudu who was adjudged the best musician at the Festival, has taken over as the leading alto in South Africa, a role for long held by Kippie Moeketsi”.

Also recorded in 1962 is the first disc by a band credited as Chris McGregor and his Blue Notes. Although both compositions are Dudu’s and it was clearly Dudu who taught Chris McGregor this lilting, suspended style of piano playing, the racial politics of the day could not see the band any other way than that the so-called “white” man was the leader of “his” Blue Notes. This automatic paternalism was to chafe sorely once the band was in exile. Ndiyeke Mra is the original title for Dudu Pukwana’s tribute — “Mra” — to the legendary band leader Christopher ‘Columbus’ Ngcukana. Both Pukwana and Nick Moyake played together for the first time in Ngcukana’s Port Elizabeth band the Rhythm Down Beat in the late 1950s. Mra was a regular favorite of the Blue Notes and their future incarnation, the Brotherhood of Breath and was also recorded by Hugh Masekela.

In 1963 the Native (Urban Areas) Amendment Act extended the apartheid government’s control on who could live in the cities and where they could live. For those born under the heat it was about to get hotter. In response to the simmering political tensions in the country The Blue Notes presented a programme of jazz and poetry in the University Great Hall at UCT on Saturday April 27 1963. The Star newspaper wrote of the programme: “The poetry is negro, the jazz Negro and African.”

Zakes Mokae, who had just returned from London where he acted in Athol Fugard’s play The Blood Knot, suggested the idea to Dudu and Chris, who wrote in the programme notes “We believe that this is the first time Poetry and Jazz have been performed together in this country. The idea was first suggested by Dylan Thomas, when he met young Negro Authors in America”. The compositions played that night included Hey Jongapha by Dudu, Linda’s Thoughts by Tete Mbambisa, Kippie by Dollar Brand and Arabia by Freddie Hubbard. The poetry set included Leroi Jones’ The End of Man is His Beauty.

JUMP CUT TO AMSTERDAM, Saturday 23rd February 1985 where Dudu Pukwana’s band Zila are playing at the Bimhuis, Piet Heinkade 3. The lineup is: Harry Beckett – trumpet; Dudu Pukwana – alto and soprano sax; Pinise Saul – vocals; Lucky Ranku – guitar; Django Bates – piano; Thebe Lipere – congas; Churchill Jolobe – drums.

By 9pm the Bimhuis is filled with the entire Mzansi exile community, not to mention every Dutch jazzer that lives in the city. Alto player Joe Malinga from Swaziland is standing at the bar next to an extremely inebriated Sean Bergin who hails from Durban, where he used to session with guitarist Kenny Hensen and bassist Brian Gibson at a nightclub called Totem at the Palm Beach Hotel in Gillespie Street. Bergin staggers around the Bimhuis chatting to anybody who will listen to him about Dudu. Bergin adores Dudu, worships Dudu. I have only ever spoken to the burly sax player a few times, and always about our mutual friend from Durban, folk guitarist Syd Kitchen, but tonight Bergin comes up to me and grabs me with both hands by the collar of my jacket, “Pellie you’ve got to interview Dudu, Dudu is the man, DUDU IS THE MAAAAN!”

An entire contingent of war resisters who live in Amersfoort have come to Amsterdam for this concert. Loosely grouped around Deezo Dumayne who left SA with his band The AK47s in 1981, the Amersfoort posse are severely stoned, surely the least “political” of all the exiles. I sit down next to Sis Harriet Matiwane who left home as a singer in the politically incorrect musical Ipi Ntombi back in 1975. She’s been working on a music career all these years but doesn’t seem to have the tenacity, the sheer dogged refusal to give up, that fellow Amsterdam resident Busi Mhlongo has. Everybody’s here tonight, but when is Dudu going to play?

Without any warning pandemonium begins. The double doors leading backstage are ripped open from within and that higgeldy piggeldy don’t fuck-with-me tone on the alto could not be anyone else. Dudu comes out of the change room like a boxer who’s just heard the bell ring for the start of the knockout round. The sound is huge, the intensity is right off the Richter scale. The band hurries to catch up with him but nobody has a chance of catching up with DP tonight.

Wise Harry Beckett, the Barbados-born trumpeter, doesn’t even try to keep up with Dudu who is playing like a man possessed. Beckett’s sweetly melodic lines are models of graceful restraint, providing a perfect foil for Pukwana’s lava-like sheets of alto madness.

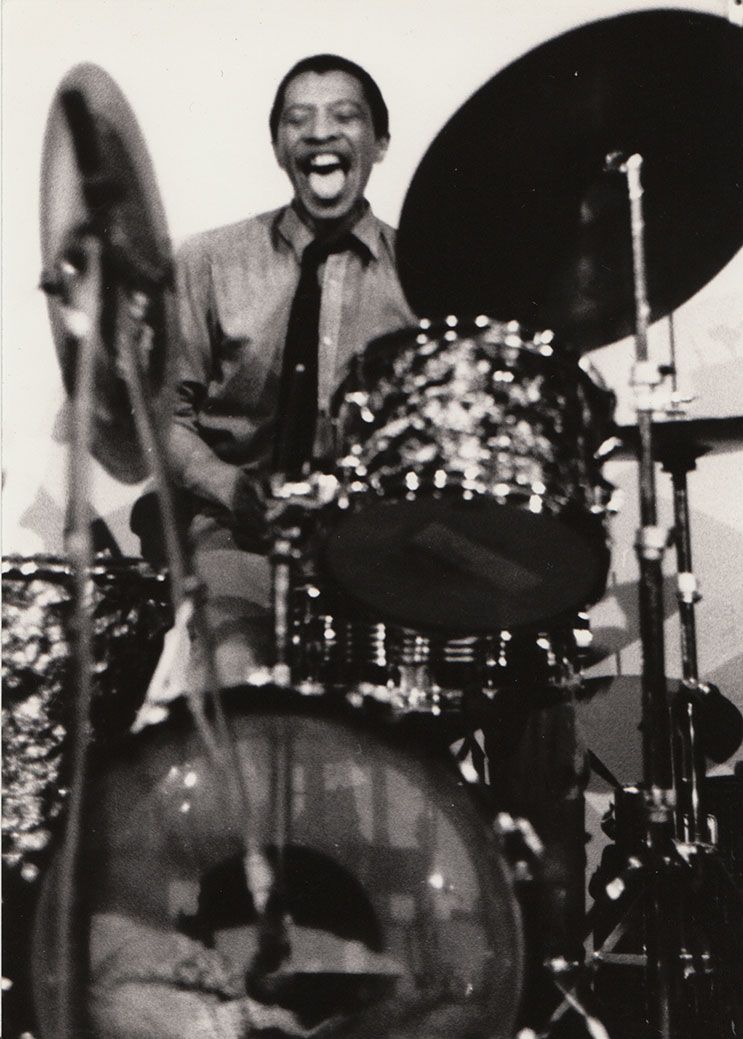

Elsewhere it’s drummer Churchill Jolobe who is the night’s great discovery for me. Completely lacking that dark sense of Chthonic menace that Louis Moholo brings to the kit, Churchill’s prime percussive motives are joy, joy and, well, … joy! It’s vulgar to use an expression like “happy as a pig in shit” when describing music but that really is what comes to mind. I’ve never seen a musician who seemed to enjoy himself as much in the playing and the sound and the sheer beingness of music as Churchill.

Standing next to Churchill, Lucky Ranku did not open his eyes for nearly two and a half hours. On and on he played, chopping the rhythms out like finely diced onions into a super salad of skanga sound. He could have stepped right out of a garage in Mamelodi so perfectly consistent was his style. In a band this great you could be forgiven for hardly noticing Django Bates on piano and Eric Richards on bass, and that isn’t because they were the only so-called “whites”.

The thing is that both of them were merely excellent musicians, almost at the top of their game. The rest of the band were South African exiles. That is to say there was something mythic about them, something tragic too, and, if I am perfectly honest, something slightly embarrassing too. Yes, embarrassing. These people gave so much of themselves you became aware of how half-hearted most music concerts were, how formulaic. I mean nothing, but nothing was pre-arranged with Dudu and the band. They had to keep their eyes open and their wits about them. He would stop in mid-flow, put the soprano down and pick up the alto and be playing a different tune within seconds, just like that, not even a miniscule nod to the head to guide his fellow travellers. They had to follow and follow closely! Everybody was on their toes, Dudu stretched those people like a veteran torturer from the Spanish Inquisition. There was no escaping it, these people were having the time of their life. There was an ecstacy and an exuberation on display that I had only ever seen in the Apostolic church when believers were visited by the Holy spirit and began to speak in tongues. What Dudu was playing outside of wasn’t just a framework of chords and harmonies, he was outside of the entire notion of audience and performer, the entire history of music as a commodity. Dudu was a natural mystic blowing through the air. He was utterly in the moment.

But was it “jazz”?

“Jazz music is an art of the spontaneous. The jazz performer and composer are the same person and the acts of composing and performing are essentially simultaneous. This is the cause of much confusion in general thinking about jazz music, and musical people thoroughly ingrained with the European tradition insist that this inevitably leads to shallow music-making. The fact is that it can lead to music-making of an almost incredible depth in performance. The performance will reflect the depth of the performing musicians’ thought at that very time”.

Chris McGregor writing from an application for a Cultural Grant, 1964.

The Blue Notes played their last gig in South Africa in July 1964. I was 4 months old. This gig was recorded by Ian Huntley and released as a cd in 2005 with an intriguing liner note: “Each listening of Dudu Pukwana’s plaintive alto sax on the essentially gloomy final track, “Close Your Eyes” sparks my own imagining of emotional turmoil and uncertainty”. I would very much like to have written that sentence because that is exactly the point. Dudu’s explorations of turmoil and uncertainty celebrated the imagination, stimulated the imagination, emancipated the imagination. The music was about freedom but not in a musical sense. Music, like politics, once proscribed as such, always had the potential of becoming a realm; a realm with borders, with boundaries. Dudu Pukwana strode across these musical boundaries like he tore through the alto and soprano saxophones that were his instruments. His realm that he played in wasn’t music, it was everywhere, it was creation itself and it was always South Africa that he was creating. Home. Ekaya.

Actually he was a piano player first. Actually Dudu was a healer. A mystic. In this sense Pukwana was the true father to Zim Ngqawana and Zim in turn, Dudu’s only rightful heir. But here in Africa South South there is nothing to inherit. Not even a new name. Only a sad direction. How you gonna be proud of a direction? Dudu never went home. He died on 29th June 1990 of a failed liver, a month and three days after Chris died. The Blue Notes belonged to both of them.

“…and anyway, Ornette was in the room. Dudu said, at intermission, ‘There’s Ornette!’ Shouting. And you know Ornette is a shy guy, everybody turned around, the whole room, ‘There’s Ornette! Where’s your horn man? C’mon? Where’s your horn? You are Ornette Coleman aren’t you?’ Damn, Dudu’s running the Cape Town thing… and Ornette was kind of panicking, Dudu: ‘Hey you are Ornette! C’mon, bring your horn, you are Ornette, ain’t you?!’ So we said, ‘Hey Dudu leave this guy, you are embarrassing this guy.’ ‘He’s Ornette!’ And Dudu’s saying it to us in Xhosa, ’I’m gonna blow his head off. I’ve been waiting for this guy.’ That’s what he said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you!’ Now Dudu he’s into another level because Dudu now was also from the other generation from Nick (Moyake), like he was prepared. Now of course Ornette was checking us out, but he was putting us as Africans, it’s-nice-to-see-you-guys kinda, they were doing that. It’s strange because the Europeans would take us for real but the American black musicians would take us, ‘Oh yeah you Africans, how do you play this?’ So Ornette had this attitude. So Dudu got mad, you know, I got mad also and Mongezi got mad. You know, this attitude!”

Johnny Mbizo Dyani,

23 December 1985

At the end of the gig I go backstage and meet my guru. He is incredibly amicable, hugs me as if he’s known me forever. I try for an hour to get something resembling an interview out of him. But very little of what is said is fit for publication. A lot of motherfucker this and motherfucker that. Dudu is mainly interested in finishing his bottle of vodka. He drinks very quickly and he doesn’t mind when the mixer runs out. His voice grows increasingly hoarse as he spins further and further away from my fanboy obsession with dates and names and genres. It takes me decades to understand how tiresome I must have been to that man who had just played himself out of the cosmos and into infinity. It’s only after being back home for fourteen years that I have finally understood that there is no home left. There never was. Once you leave home you can never go back. You become an exile and exile becomes your only home. Actually it’s better that Dudu didn’t live to find that out. Maybe he already knew that. Maybe that’s why he literally killed himself for us, tearing South Africa out of himself in order to give us a little piece of sonic myth we could identify with and feel at home in. When Dudu played we forgot that we were in exile.

All photos by Aryan Kaganof using an Olympus Trip camera and shooting on Kodak Tri X Pan 400 ASA film pushed to 1200, except for the photos taken backstage of Aryan Kaganof with Dudu Pukwana in the change room at the Bimhuis, which were taken by Sarah Hills on the same camera. Printed on Ilford paper in the darkroom of Kier Schuringa on Burman straat.