GEORGE KING

Unknown, Unclaimed, and Unloved: Rehabilitating the Music of Arnold Van Wyk

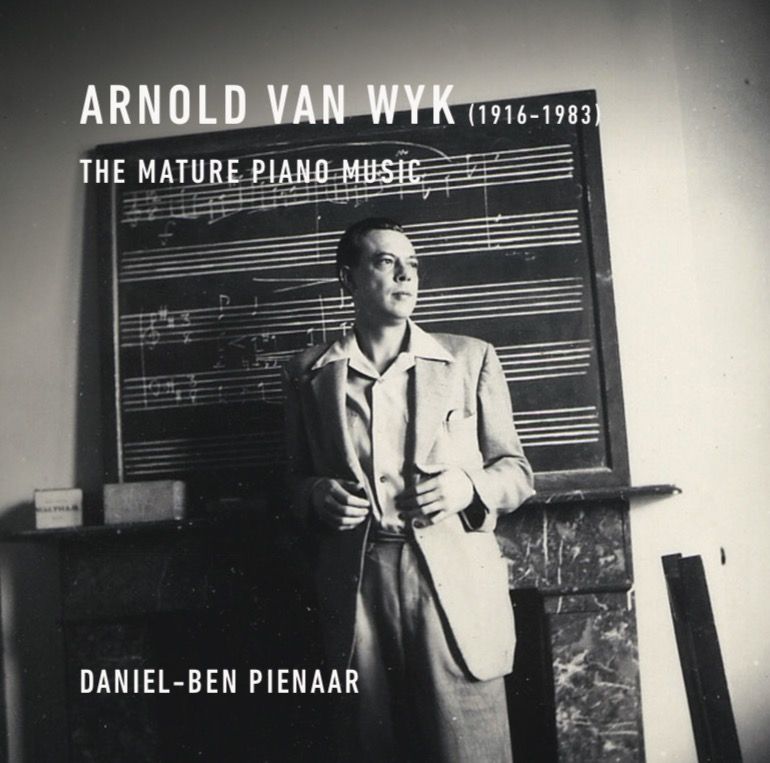

Arnold Van Wyk (1916-1983): The Mature Piano Music. (Night Music,1955-8; Ricordanza,1973-9; Four Piano Pieces,1965; Pastorale and Capriccio,1948, rev. 1955; Tristia,1968-78. Daniel Ben-Pienaar, piano. AOI CD04, 2021.

August 2014 saw the official launch, first in Stellenbosch, then in Pretoria, of Stellenbosch University musicologist Stephanus Muller’s monumental Nagmusiek (Night Music). Biography, catalogue and work list, the three volumes of Muller’s magnum opus include a detailed documentation of manuscripts, sketches and fragments of the South African composer Arnold van Wyk (1916-83). It is also, Annemie Behr reminds us, not only these considerable things but ‘deliberately ideological: to establish and confirm the importance of a largely marginal figure through an act of canonising’ (Behr 2014, 133).

Nagmusiek is not only the title of Muller’s literary and scholarly publication of 2014 but also that of van Wyk’s best-known and most celebrated piano work Nagmusiek,completed in 1958 and the centrepiece of the newly-released CD of the composer’s mature piano music reviewed here. The liner notes inform us that the disc ‘is an important step towards appreciating the significance of Van Wyk’s creative achievements. Not only because he was a pianist, and wrote idiomatically for the instrument from a very young age, but also because Night Music, the centrepiece of this CD, is one of his very finest works in any genre (Muller 2018b, 8).

Born into a struggling Afrikaner farming family near Calvinia, a desolate Karoo town in the Northern Cape, Arnold van Wyk was nevertheless able to attend high school in far-away Stellenbosch where he subsequently began university studies towards a BA degree. These studies were interrupted when in 1938 he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music in London. The Second World War then broke out, so he continued studying at the RAM until 1944 and remained in London for the entire duration of the War.

During his London years van Wyk began developing his creative identity, stimulated by the musical life of a major metropolis. Between his studies and eking out a living with various jobs such as translating and reading the news on the BBC’s Afrikaans service, he composed some impressive works. Five Elegies for String Quartet appeared in 1941 and was premiered in February 1942 at the National Gallery (London) by the Menges String Quartet. It was van Wyk’s most important composition to date (Muller 2008b, 65). Three of the elegies were subsequently revised and the definitive version given a performance two years later. It was this work too that attracted the attention of Howard Ferguson, the English composer, musicologist and pianist who became a close friend of van Wyk for the rest of his life. (Ferguson also wrote the entry on the composer for The New Grove Dictionary of Music of 1980.)

Another substantial work from the war years is his First Symphony in A minor, which received critical acclaim following its premiere under Henry Wood. Significantly, the performance was given on 31 May 1943, Union Day in South Africa and broadcast to this country. Muller points out that the BBC gave clear instructions ‘to use this fact as propaganda to a large Afrikaner constituency sympathetic to Germany’; he also calls the Symphony ‘one of the most convincing large-scale pieces van Wyk ever wrote’ (Muller 2008b, 67). The Symphony also impressed John Barbirolli, who conducted it on at least one occasion in England, in 1951.

In 1946 van Wyk returned to South Africa, taking up a lectureship in the College of Music at the University of Cape Town. He resigned from his post in 1960, having decided he could no longer work with the head, Eric Chisholm, and he wanted ‘to be rid of that place and working under strain and unpleasant conditions once and for all’ (letter to his lifelong friend and confidant Freda Baron in Muller 2008b, 72). Notwithstanding his revulsion for what he considered to be uncongenial working conditions, it was in Cape Town that he completed his Pastorale and Capriccio (written in 1948 but revised in 1955) and Night Music, in 1958. However, taking on a lectureship at nearby Stellenbosch University was, in Muller’s estimation, ‘second only to returning to South Africa … arguably the biggest mistake of his career’ (2008b, 72).

Van Wyk made little impact during his eighteen years at Stellenbosch, loathing his teaching duties as well as the overbearing atmosphere of a university which had produced Afrikaner nationalist leaders such as Hendrik Verwoerd and John Vorster. Added to this, his ‘discreet homosexuality’, lack of affiliation to any of the Afrikaner churches and absence of overt support for the government’s apartheid policies (though he was careful not to criticize those policies publicly) may have militated against advancement within his department (Muller 2008b, 73). Van Wyk also became increasingly disillusioned with the Afrikaner political establishment because of what he saw as ‘meagre opportunities and inadequate support for South African composers’ (see Muller 2008a, 293). But, as Muller reminds us (2008b, 77),

there is no doubt that [van Wyk] benefited enormously from the Afrikaner dominance of South Africa. It was this dominance that ensured the status of Western art music in the Republic as the privileged form of musical expression of a white minority elite. Government support saw the construction and funding of major theatre complexes, concert halls, opera houses and university music departments. … Van Wyk’s career was serviced by this structure, and he enjoyed the patronage of some of the most powerful and influential role players of the time. … For all his difficulties as a composer in a country without much appreciation of his art, whatever van Wyk did manage to compose, was nearly always guaranteed a performance and a commission (the latter often in retrospect).

Experiencing barren creative periods at various times throughout his career, especially towards the end of his life, van Wyk produced a relatively small corpus, though he did write works in almost all genres except opera. The best of his music is outstanding: distinctive, imaginative and technically polished. Apart from those mentioned earlier, together with the First String Quartet (he never wrote a second), his best-known works include the four songs under the title Vier weemoedige liedjies (the earliest pieces the composer thought worth preserving, 1934-38), the song cycle Van liefde en verlatenheid (1948-1953) – which Howard Ferguson (1980, 554) describes as ‘combining a deep sympathy for the peoples and landscapes of his country with unrivalled skill in setting the Afrikaans language’ – a less successful Second Symphony (‘Sinfonia ricercata’), the orchestral Primavera (1960, virtually a third symphony), other songs and a good deal of excellent chamber and choral music as well as works for piano, including Night Music.

It was during his years in Stellenbosch that he composed and completed Four Piano Pieces (1965), Tristia (1968-78) and his last piano piece, the remarkable Ricordanza (1973-9), all of which more later. When he died he was working on the a cappella choral work Aanspraak virrie latenstyd (1983), with six of its projected twelve songs completed. But the undoubted crowning glory of his final years and perhaps of his career as a whole was the Missa in illo tempore for double choir and boys’ choir (1979). A substantial work he had been working on sporadically for over thirty years, it was his response to a commission from the Stellenbosch Festival Committee for a large-scale work to celebrate the town’s tercentenary in 1979. In this last stage of his career van Wyk realized an ideal opportunity to make a political statement that was close to his heart (see Muller 2008b, 76). Giving a defiant finger to the authoritarianism of the Afrikaner establishment which he had loathed all his life – despite his Afrikaner origins and deep love for his native tongue – he offered a setting of a Roman Catholic liturgical text in Latin for performance in a Dutch Reformed church in the ideological birthplace of apartheid. Was this when van Wyk felt gratified by finally making his mark on his fellow Afrikaners, and they in turn were duped into falsely believing that they were truly upholding the banner of Western Christian civilization on the southern extremity of Africa (see Praeg,) In any event, the performance was repeated a few days later in the more congenial setting of St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town.

In his review for Rapport (quoted in Muller 2014, I/796, 798) the composer Stefans Grové wrote perceptively: ‘Arnold van Wyk’s work is a heartfelt manifestation of a highly strung observer of the crassness, horrors and violence of our century … This masterpiece ought to become part of the repertoire. There are many choirs in our country that can manage it and perform it repeatedly’ (my translation). It is yet another irony surrounding the composer’s posthumous status that there seem to have been very few if any further performances of it in this country over the last forty years.

The CD under review here, Arnold van Wyk (1916-1983): The Mature Piano Music, with South African pianist Daniel-Ben Pienaar and released in 2020,comprises five of van Wyk’s piano works spanning a period of just over thirty years from the late 1940s to the late 1970s. Spread over eleven tracks, they are presented on the disc in this order: Night Music (1945-58), Ricordanza (1973-9), Four Piano Pieces (1965), Pastorale and Capriccio (1948, rev. 1955) and Tristia (1968-78).

The major work on this disc, occupying Track 1, is undoubtedly Night Music (Nagmusiek). ‘A moving tribute dedicated to the memory of the young Australian pianist Noel Mewton-Wood’ (Ferguson 1980, 554), it’s been described variously as ‘Van Wyk’s finest piano work’ (Walton 2015, 116) or ‘Van Wyk’s piano masterpiece’ (Tyrrell 2017, 153), a piece that emerged after a gestation period of thirteen years. In a letter dated 25 June 1958 Arnold van Wyk wrote to his conductor friend Anton Hartman at the SABC:

I am now doing very well – I can manage my work at the College and I have also thank GOD finished the Night Music after a painful struggle, more painful than anything I have ever experienced before. (Also just in time: I have had a request for a first European performance from the Macnaghten concerts and the work is now in England already for them to perform.) (My translation.)

Van Wyk’s choice of Night Music (Nagmusiek) as the title of the piece invites comparison with Hungarian composer Béla Bartók’s celebrated ‘night music’ passages occurring in a number of his works. To take one example: in commenting on Bartók’s Divertimento for String Orchestra,László Somfai notes that ‘The Molto adagio middle movement belongs to Bartók’s night music topos: a sorrowful violin melody followed by a Hungarian lament, then cries and shouts, with a return to the extremely expressive chromatic melody – one of the most moving pieces he was ever to write’ (Somfai 2006, 6). It is surely stretching things too far to claim any particular affinity between Bartók’s passages of night music and van Wyk’s Night Music. Yet Ribeiro (2009, 57) points out that ‘Van Wyk made many detailed instructions in the score of Night Music and, with reference to character; he made use of unusual terms such as glacial, niente, lugubre or spetralle. It shows that the composer was expecting great depth of interpretation and spiritual insight of the performer.’ With their connotations of loneliness, rejection or desolation – icy, nothing (or empty), mournful, spectral or ghostly – these performance indications evoke a range of disturbing but heartfelt emotional moods throughout the work’s seven sections. They are of a piece with van Wyk’s ambivalent feelings towards his head of department at the university where he worked during the late 1940s and the 50s, his antipathy towards the apartheid Nationalist government’s policies in South Africa, the despondency he felt with the cultural poverty of his country, and his thwarted, half-repressed homosexuality. His close friend Howard Ferguson described Night Music as one of the composer’s ‘most characteristic works’, combining ‘intense feeling with warmth and sensitivity’ (Ferguson 1980, 554).

What we do know is that van Wyk himself felt deeply moved when performing the work. Izak Grové tells us that ‘at least one person (the late Chris Swanepoel) who was present during one of the first public performances of the work by the composer himself (presumably the performance of 1956) has on more than one occasion referred to the composer’s visible discomposure during the performance’(Grové 2008, 11; my translation from the Afrikaans). He further suggests that in this work van Wyk created two different worlds: on one hand an ‘abstract’, ‘objective’ art work that is comparable to any by Liszt or Ravel in terms of artistic success and satisfying musical parameters such as form, balance and variety, while on the other hand it is also a document, like the later Ricordanza, ‘that offers insight into personal circumstances and an opportunity to “say” what could not be said in another way’ (Grové 2008, 11; my translation).

What of van Wyk’s own reaction to others performing the piece? In a letter to Anton Hartman dated 22 February 1973 he writes:

[Lamar] Crowson was also there, as one of the ±fifteen (!) in the audience. We are good friends (although I, at least, am a little scared of him) and he told me last night, as he has done on many previous occasions, how much Night Music means to him. And I believe him, because of all the pianists I have heard so far, his interpretation of this music has moved me the most.’

(Vos and Muller 2020, 411; my translation. The pity is that we have no recording of Crowson performing Night Music.)

In 1968 the Financial Times music critic Ronald Crichton, reviewed John Ogdon’s performance of Night Music and gave his impressions on the style of the piece:

…in style Night Music is related to the piano works of Debussy and Ravel, and, more strongly, to the late works of Fauré … even if Mr. Van Wyk were to assure me solemnly that he didn’t know or didn’t like the later works of Fauré, I should still insist that Night Music, in mood and atmosphere as well as in the way much of it is written, inhabits the same lonely, subtly original world.

(quoted in Nöthling 2014, 8)

Almost too late for my publication deadline, Aryan Kaganof drew my attention to several illuminating pieces on Night Music that appeared last year in issue 3 of herri that I had inadvertently overlooked. Taking their cue perhaps from Muller’s methodology in his sprawling 2014 biography of van Wyk they approach Night Music more in the form of literary, philosophical and psychological reflections on the piece (and on Muller’s biography) than in purely conventional musico-historical terms, as I have done in this review. Their very different but thought-provoking commentaries shed light on aspects of the work I had not thought of nor considered here. For instance, Leonhard Praeg asks What is the meaning of the composition Nagmusiek? Is that even a real question? After all, if Van Wyk could have answered that question he would not have needed to compose the piece. The meaning of a musical composition is always radically irreducible to the meanings language can ascribe to it. We can circle Nagmusiek like a pack of hyenas, but we can’t tear at its flesh.

Later he writes astutely about van Wyk’s use of conflicting tonalities as a way of unlocking or decoding aspects of the composer’s (homo)sexual life, and proceeds to question the point of the whole canonisation process and the relevance that both Muller’s complex biography-cum-catalogue and indeed the creation of the Night Music CD might have for us today.

For Tom Whyman, Night Music attempts to represent an absence – in so doing, it makes said absence present. This paradoxical present-absence is, I think, the very possibility of a different self, whose choices were made as part of a different past; from which was formed a present that maybe could have once been, but never can be now. Nagmusiek mourns Mewton-Woods, but it is not, strictly speaking, haunted by him: it is haunted by a different Van Wyk.

Whyman writes extensively in his piece about the concept of ‘hauntology’, a term he tells us was coined by Jacques Derrida to denote the study of what is not: what does not exist might nonetheless ‘have certain real effects’. It has a ‘presence’ that is ‘virtual’ and ‘insubstantial’, and can even ‘fold back on itself’, just as the achronistic, neo-Romantic Night Music attempts to remove itself from history and could be said to exemplify ‘a hauntology of the self’. We are now in deep waters, philosophically speaking; the discerning reader will want to study both Whyman’s and Praeg’s pieces for their absorbing insights into van Wyk’s Night Music. Another intriguing spinoff from van Wyk’s piece, described in the same issue of herri,was the attempt to create ‘a visual translation, rather than an interpretation’, of van Wyk’s vision – ‘not to explain what you’re hearing, but to render it into moving image’ (Panoussis). These discussions all provide us with stimulating ways of getting to grips with ‘meaning’ in the musical work that is Night Music.

If Night Music is the major piece on this disc, then Ricordanza which follows it on track 2 is perhaps the next most intriguing of the remaining shorter piano works. Ricordanza (‘remembrance’, ‘recollection’) is the last piano piece van Wyk’s was to compose. It was completed in 1979, the same year as the Missa. It has at times a whimsical quality, what Muller refers to as ‘Van Wyk’s Romantic sound world’ (Pienaar and Muller 2020, 17). Long before, Busoni had referred to Liszt’s Ricordanza as ‘a bundle of faded love letters’ (Samson 2003, 184, quoted from Ferruccio Busoni, The Essence of Music, p.129). Ricordanza certainly evokes to some extent a man in his late 50s looking back nostalgically to the world of Schubert and Liszt – the Romantic music he grew up with and loved. To quote Muller again: the piece is ‘almost Proustian in its evocation of things past: harmony as it used to be, melody as it might have sounded in a world where the culture of suspicion has not taken root …’ (Pienaar and Muller 2020, 17). It is an absorbing late work whose wistful character Pienaar captures to perfection.

The Four Piano Pieces (tracks 3-6) were composed in 1965 for the University of South Africa’s music examinations. If they are slighter than the previous two works on the disc (the longest of them takes less than five minutes to perform and the shortest less than two minutes), they are nonetheless characterful and technically challenging. They are followed on tracks 7 and 8 by the earlier Pastorale and Capriccio, composed in the late 1940s and revised in 1955. Pienaar calls it ‘an effective concert piece by a relatively young composer who has a voice, and knows how to write well for the instrument’ (Pienaar and Muller 2020, 20), inevitably overshadowed by the weightier Night Music but well worth hearing all the same. The three short movements of Tristia (1968-78) – Rondo Desolato, Ostinato and Berceuse – provide just over twelve minutes of music in total, but they confront the listener with worlds of extraordinarily varying expression. For Pienaar,

The ‘Rondo Desolato’ (in my opinion a staggering bit of piano writing) speaks to me of an insurmountable kind of sadness, something that is beyond overt ways of expressing it, or maybe of a kind of fixed point from which one yearns to move, but to which one is always dragged back. For me the way to make that real at the piano was to think of the desire to move, the desire to communicate through statements that naturally ebb and flow, and then to not allow it, as it were – constantly straining against the tyranny of a measure pulse, only sometimes briefly winning out. … [I]n the context of the three pieces [the ‘Berceuse’] feels to me that its easy, undulating rhythm, and the rather obvious lushness are almost too good to be true – as if the way the ‘Ostinato’ quietens down on its final page were no more than a trick of stagecraft. The ‘easy-going’ aspect of it is, however, partly due to my deciding on a faster tempo than Van Wyk’s metronome marking … So one ends up, with Ricordanza, the ‘Rondo Desolato’ and the ‘Berceuse’ representing very different ways of singing or tryingto sing, and of slow movement.

(Pienaar and Muller 2020, 18-19)

One could not wish for a more exemplary production. Liner notes are contained in a booklet which in addition to the usual artist’s biography and programme notes includes the absorbing and illuminating eight-page interview with Pienaar by Stephanus Muller from which I have quoted liberally here. It gives the reader-listener many revealing insights into the pianist’s thoroughly meticulous preparation for the recording. It is well worth spending time reading and re-reading the discussion for the light it sheds not only on Pienaar’s approach but also on aspects of the music that the listener might not otherwise be fully conscious of.

It goes without saying that Pienaar is a consummate musician who brings not only a technical mastery but especially a finely-considered, mature approach to the qualities and character of each piece on the disc. The piano – itself a particularly fine instrument – sounds extremely natural, while the recording was made in England with Philip Hobbs as sound engineer. Pienaar took pains with his sound engineer to consider the ambient sound of the instrument in its recording venue and how it might best be captured technically on disc. He describes his approach:

When thinking about recorded sound I keep in mind that when one plays in a hall there are many truths that can be captured by the microphones. Think for example how different the same performance can sound from different parts in a hall, or if you have your back turned, even, or of how it feels from where one is sitting playing. So it is an important part of every project to consider which of these truths are closest to one’s aesthetic intention for a particular project. What space does one want to evoke for the listener? I do not particularly enjoy recordings where an empty hall is evoked, so I am always keen to move away from the ‘default’ glamorousness that seems to be a production standard these days. To think more in terms of a decent-sized salon with nice wooden floors, maybe even some wood side panels, something like that.

(Pienaar and Muller 2020, 15-16)

In his interview, Muller asks: ‘In preparing for the Van Wyk recording, you were adamant that you needed to hear all previously recorded version of the music that I could send on. I was somewhat perplexed by this, as, to my mind, Van Wyk’s music doesn’t have a “recording history” that has in itself become a text that informs the works.’ To which Pienaar replies:

My simple impulse was one of ‘due process’ … I believe that any music worth doing will, as time passes, become not just different, but often more what the composer could have imagined. … My idea with music that is as finely made as this, with such compositional finish and so rich in its literary sensibility and in its awareness of the world of gesture and diction and enunciation and sound colour, and that, as yet, does not have a tradition of recordings or performances of different kinds to go alongside it, is to play a game where I imagine such traditions might exist and what they would be based on my experience of what performers do in the repertoire that I normally play.

(Pienaar and Muller 2020, 14)

The composer himself recorded Night Music in 1963, but we are told the sound quality is poor (Riberio 2009, 57). Several leading South African pianists have since recorded Night Music. The most recent of these are by Jill Richards in 1992 and Benjamin Fourie in 1998; both are now well over twenty years ago and difficult to come by, though the Richards performance is available here. While each of them has many merits and is worthwhile, the sheer overall artistic and technical excellence of this new one – with the very considerable bonus of having all of the composer’s mature piano music on a single disc – make it a must-have for lovers of twentieth-century piano music and those with an interest in South African concert music.

Arnold van Wyk stands out as the leading and most respected South African composer of Western concert music of the mid-twentieth century. He is the only South African composer who was considered sufficiently noteworthy for newspapers across the country to have reported his resignation from a university post. The year was 1978 and he was only 62. The position he resigned from was a lectureship – not a professorship or even a senior lectureship – which he had held at Stellenbosch University since 1960. That the composer’s decision to leave his post after nearly twenty years made the news at all gives some indication of his standing within apartheid South Africa in the late 1970s, despite his liberal outlook and abhorrence at the government’s policies. Very little of his music is heard today; this new recording deserves to be welcomed enthusiastically. For all that, van Wyk remains, as his biographer Stephanus Muller reminds us, ‘to a large extent unknown, unclaimed and unloved in South Africa’ (Muller 2008b, 77).

Behr, Annemie. 2014. ‘Nagmusiek’, book review in Muziki 11, 133-135. 10.1080/18125980.2014.995285.

Ferguson, Howard. 1980. ‘Wyk, Arnold(us Christian Vlok) Van.’ In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. S. Sadie, vol. 20. London: Macmillan.

Grové, Izak. 2008. ‘Lewe-ín-Werk: Outobiografiek in Arnold Van Wyk se Musiek’, Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 48/1 (March 2008), 1-12. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Kruger, Lou-Marie. 2014. ‘Nagmusiek deur Stephanus Muller’, review article, Litnet Accessed 4 October 2021.

Muller, Stephanus. 2008a. ‘Arnold Van Wyk’s Hands.’ In Composing Apartheid, ed. Grant Olwage. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Muller, Stephanus. 2008b. ‘Arnold Van Wyk’s Hard, Stony, Flinty Path, or Making Things Beautiful in Apartheid South Africa’, The Musical Times 149/1905 (Winter, 2008), 61-78. Accessed 5 September 2021.

Muller, Stephanus. 2014. Nagmusiek. Three vols. Johannesburg: Fourthwall Books.

Nöthling, Grethe. 2014. ‘A Performance Guide to Arnold Van Wyk’s Early Solo Piano Compositions’. Unpublished DMA thesis, University of Iowa. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Pienaar, Daniel-Ben and Stephanus Muller. 2020. ‘Daniel Ben-Pienaar in Conversation with Stephanus Muller’. Liner notes for AOI CD04, Arnold Van Wyk (1916-1983): The Mature Piano Music.

Pistorius, Juliana M. 2015. Review of Nagmusiek [Night Music] by Stephanus Muller, Fonts Artis Musicae 62/2 (April-June 2015), 130-132. Accessed 5 September 2021.

Ribeiro, Pinto. 2009. ‘Exploring Authenticity in Performance: A Comparative Performance Analysis of Arnold Van Wyk’s Night Music for Piano’. Unpublished M.Mus. thesis, Stellenbosch University. Accessed 15 September 2021.

Samson, Jim. 2003. Virtuosity and the Musical Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schneider, D. 2006. ‘Bartók, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality.’ In California Studies in 20th-Century Music. ISBN 978-0-520-24503-7

Somfai, L. 2003. ‘Invention, Form, Narrative in Béla Bartók’s Music’, Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 44(3/4), 291-303. Accessed 25 October 2021.

Tyrrell, John. 2017. Review of Nagmusiek by Stephanus Muller, Music and Letters 98/1 (February 2017), 153-155. Accessed 17 September 2021.

Vos, Stephanie and Stephanus Muller, editors and annotators. 2020. Sulke Vriende is Skaars: Die Briewe Van Arnold Van Wyk en Anton Hartman, 1949-1981. Pretoria: Protea Bookhuis.

Walton, Chris. 2015. ‘Review: Something of the Night’, The Musical Times 156/1933 (Winter, 2015), 116-118. Accessed 5 September 2021.