Will contemporary art curators live up to their professional duties as custodians and protectors of art? Or, do they prefer to deleteriously regard censorship as a third-world problem and perhaps a faraway, even Oriental phenomenon?

For a whole spring and summer it stood, towering, ninety years after the burning of hundreds of thousands of books declared ‘UnDeutsch‘ in the Friedrichplatz of Kassel. The Parthenon of Banned Books loomed as a towering, playful and enigmatic construct.

Argentinean artist Marta Minujín (Argentina, 1943) built a castle of censored books that took the shape of the Ancient Greek Parthenon temple, though adorning a far more gray, droll and significantly less exciting city than Athens is at any time of the year. The small German city of Kassel enjoys renown for its art fair, and munitions factories. In addition, Kassel enjoys renown in Montenegro, for featuring the pool-bar parties at Bar-Hotel Montenegro, the sole local ”Balkan” referencing-landmark before contemporary Greece became a place of fascination for the team of international curators, who hold their congresses in Kassel every 5 years.

Adam Szymczyk, then the lead-curator starring at Documenta’s 14th edition, said of the Argentinean artist’s Parthenon, “Censorship, the persecution of writers and the prohibition of their texts motivated by political interests and attempting to influence our thoughts, our ideas, and our bodies is once again widespread today. The Parthenon of Banned Books sets an example against violence, discrimination and intolerance.”[1]Parthenon of Books Rises in Athens Sikiardi, Kerry. Jun 2017 article in Eu Greekreporter. Web..

Held together by industrial plastic in the shape of the ancient Athenian Parthenon temple, Minujín’s Wisdom-temple was a work of self-replica, self-referential, of the oeuvre of one of the most outstanding and successful Latin American designers. Parthenon II offered a plasticized shadow of the first such conceptual monument the artist had assembled, as a young temple architect in 1983, when the Argentinean Parthenon I monument she constructed was a requiem to the most-infamous Argentinean military dictatorship’s policies of censoring literature. The first Neo-Classicist monument used used all the titles of books banned by the military junta as building-blocks. Had any Junta officials seen Minujín’s temple, they would have judged it as evidence of the Judeo-Masonic-Bolshevik conspiracy they believed in (though today the Argentinean retrospective defenders of the military coup claim that anti-semitic ideas have lost traction).

To build anew an ancient Greek Neo-Classicist temple implied all the styles and motifs of Fascist design and architecture in Europe. Though Argentinean Fascism was never static enough nor sufficiently creative to have an architectural style – beyond austere, purely practical monoliths lacking balconies – the country’s ruling ideologues found their inspiration in the German, Spanish and Italian Fascisms of the 20th century.

Not long ago, Athens still represented the beacon of democracy and the ancient origin of humanism. Today, when Argentineans hear ”Greece” the word more likely summons images of financial crises affecting what seems a similar, even related people and culture in the faraway Balkans. This time around, Minujín did research that seems far more lighthearted than the 1983 monument of books blacklisted by ruthless Argentinean dictators. The recent castle, for example, contained copies of Alice and Wonderland : forbidden by Maoism for its seemingly anti-agricultural message; and Little Red Ridinghood: forbidden in Franco’s Spain, because of the Red coat….

Strangely, for a statement about omitted information, Minujín and Documenta seemed eager to collaborate with the highly-corporate Frankfurt Book-Fair, known to strictly emphasize marketing over any love for books and the bookish.

Contrast Minujín’s playful endeavor with her first Parthenon. 1983 in Argentina: an artificial political Spring hung in the air, as the dictatorship had just ceded power after the self-destruction of its international image aided by international reports and witnesses to atrocities. (My family members, artists menaced by Junta violence against artists, had not yet returned to the country; some never would.) Democracy was a gift granted on the condition of a form of censorship, or a code called Amnistía under which the polarized factions of the Argentinean people went about agreeing to self-censorship in different forms, in order to protect culprits.

The pact of self-censorship and memory-erasure — a bloody betrayal in the eyes of many who held grievances — passed under the dubious moniker of Amnistía, a false promise of redemption, offering non-prosecution for war crimes ”on both sides”, implying that crimes on the side of the usurping coup’s military and the resistance panned out evenly. Argentine society has always loved and feared its own polarization, living in tension between these opposing forces. While many books were banned, translations of German Nazi literature forbidden then in Europe enjoyed a publishing revival in Argentina. Dictatorship made way, thawing into a democracy that would informally agree to non-interference with the neoliberal economic project originally imposed, like a Trojan horse, by the gentlemen of the Junta at the behest of global financial firms.

Banned books of Minujín’s first Parthenon included Kiss of the Spider-Woman by Manuel Puig, and books of satirical tales by Julio Cortázar, Griselda Gambaro, the pornographic-psychedelic adventure novel Strip-tease by Enrique Medina and many classic works of literature.

Banned books in Documenta’s recent Parthenon II listed titles like Khaled Hosseini’s best-selling airport novel The Kite Runner, and other books censored or deemed controversial in Iran, Russia, Afghanistan and Maoist and capitalist China. These are the regimes most often associated with censorship in the Western media: Afghanistan, Russia, Iran, China. According to Documenta, the contemporary art world (which includes the literary and academic worlds) refuses to succumb to such normalization of censorship. Boards of censorship are often called by their names in countries like Iran. In the West, those at the forefront of censorship favour entirely different terminology. Perhaps they will invoke the battle against ”fake news” as did Macron recently, echoing the NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg’s pieces published in European newspapers advocating a ban on fake-news, requested by a sprawling military organization that identifies as aggrieved victim of ”fake-news”.

How would an artist like Orson Welles fare in the contemporary environment? Would Orson Welles have been more strictly censured ? Or do first-world Western societies enjoy an admirable absence of censorship?

Censorship, according to liberal and art-world understandings, appears to be an Asiatic phenomenon. When censorship rears its head in Western 21st century societies, then it goes by a different name — perhaps ”de-platforming”, ”safe space”, ”contextualization”, or other terms infamous and in-vogue of late.

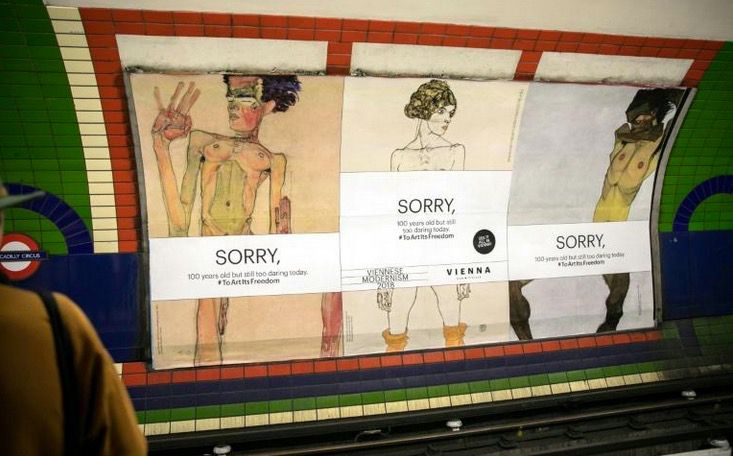

When genitals were removed from posters of nudes by Austrian painter Egon Schiele in London in 2017, surprisingly few art-world entities made any outcry of solidarity with the dead artist.[2]Nella Londro del sindaco Sadiq Khan le Opere Schiele Tornano

Or take, for example, when the New York businesswoman Mia Merrill, in her petition demanding the removal of Balthus’ painting Thérèse Dreaming from the Metropolitan museum in 2017, asked for a ”corrective text” to ”contextualize” the painting lest it spark sexually harassing behavior among those who corporate feminist Merrill refers to as the masses in her pamphlet.[3]Showing Balthus at the Met isn’t about Voyeurism, it’s about the Right to Unsettle Laura Elkin, article. Dec 2017, Frieze Magazine Web.

Yet another recent morbidity from last year: when an artists’ collective led by British artist Hannah Black at the Whitney Biennial insisted that ”censorship” was not a a fair description of their demand for the public burning of the painting Open Casket by Dana Schutz. The painting needed be burnt in public, according to their online petition, to punish a white artist for having depicted an historical scene of a murdered black man. The accusing activists entirely ignored the presence of black Californian painter Henri Taylor at the biennale. Taylor, a maestro of paint, showed work depicting contemporary tragedies of police shootings.

Why, then, was contemporary censorship not more of a ‘’hot topic’’ at the Documenta quinquennial — considered by many to be a definitive event in the art-world? Documenta, for both its friends and critics, is known as a wagging of consciences by international curators, who use the exhibitions at the sites of holocaust-era atrocities to discuss how lessons from history still apply to our day.

By the time of Documenta festival of 2017, Argentina had again become a country in which state-censorship ran rampant, even less democratic than in 1983. Despite the intention at commemorating the Nazi and Junta book-burnings, the list given to Minujín by the Frankfurt Book-fair monumentalized irony and wishful thinking, with a wide array of books censored by the defeated totalitarianisms of the past. It would be a far too easy, even self-defeating critique, however, to jump at the opportunity of invoking Orientalism, in that vacuous, vindictive way the theory is usually wielded: as a weapon for academics to limit creative expression and discussions about Non-Westerners taking place in the West.

Minujín follows her curiosities to the best of her abilities—”from each according to his ability, to each according to his need,” as both Perón and Chairman Mao, secret allies of the Little Red Riding Hood, and sworn Cold War enemies of Alice in Wonderland, have said.

Not very far from the Parthenon of Kassel, and not very far from the Black Forest birth-lands of Grimm’s Little Red Riding Hood, a censorship battle simmers on since 2016, around a poem written on a wall — a poem in Spanish, a poem from South America and the previous century, that makes references to boulevards, and to women, and flowers. Leftist women enrolled at the Alice Salomon Hochschule filed a petition demanding the poem be painted over.

Bolivian-Swiss poet Eugen Gomringer, one of originators of the South American Concrete Poetry movement in 1951, is in his early nineties and embroiled in a courthouse imbroglio, fought to prevent the removal of his poem from a school wall. The threat came only 5 years after being painted, when that very same Alice Salomon Hochschule awarded him the Alice Salomon Poetry Prize. The poem, Avenidas, translates as

Avenues

Avenues and flowers

Flowers

Flowers and women

Avenues

Avenues and women

Avenues and flowers and women and

an admirer.

In Spanish, admirador contains mirador, the observer. Painted in large lettering on the south facade, the poem stood in the crosshairs of outraged students who issued an open letter stating this poem not only reproduces a classic patriarchal art tradition in which women are exclusively the beautiful muses that inspire masculine artists to creative acts, it is also reminiscent of sexual harassment, which women are exposed to everyday.[4]Grenier, Elizabeth Berlin College To Remove Mural Poem Deemed ”Sexist” article, January 25 Deutsche Welle web

The poem was painted over after a lengthily protracted mock-trial.

”Censored” — the word that feminists since Catherine Mackinnon don’t want to hear when they prefer other terminology more favorable to their circles when it comes down to the images they find disgusting.[5]Perhaps the problem in this kind of thinking was already exposed by John Coetzee in his essays ”Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship” when he wrote about feminist Catherine Mackinnon’s discourse on pornography. For thinkers like Mackinnon, use of the term ”censorship” is only appropriate if the political rationale of the censor is sympathetic or seems justified. Justifiable censorship necessitates a different vocab altogether, it would seem. Kassel’s curators invoked artistic freedom recently when they came under attack for allegedly ”misspending” German money on Athens, a controversy that reflects some of the real ideology and ruling values of the financial benefactors behind the mega-show of the well-intentioned. But when it comes to the violation of the poet

Gomringer’s artistic freedom, the academic curators of Kassel would be more prone to shrug, Platonic Guardians not fond of poets in their republic.

Perhaps a far more direct and brutal form of censorship than the battle around the concrete flower poem, was enacted by South African curators, students and art-world activists in Capetown, featuring the burning of around 75 paintings, including Hovering Dog by South African poet, visual artist and veteran anti-Apartheid dissident Breyten Breytenbach on the Capetown University Campus in February 2016.[6]List of art-works destroyed or removed at Capetown University in Ground Up Zimbabwean magazine Leaked document. Web

The riots that led to the burning of art works rose in tandem with the Rhodes Must Fall Movement, of students agitating to have monuments to colonial ideology removed from public view. To have Rhodes statues removed does not seem such an odd idea—usually, when a regime falls, monuments of the defeated regime can be assigned a new context, hopefully in a museum. Strangely, the attacks targeted and burned works by African contemporary artists who resisted Apartheid when they lived under that toppled dictatorship. Breytenbach did time in prison for resisting Apartheid.

When the poet’s drawing titled Hovering Dog got mentioned as one of the destroyed art-works in a document leaked to Ground Up magazine (the University refused to speak to the press) Breytenbach joined David Goldblatt and other artists in levelling their complaints that the University had not respected their rights in the South African democratic (post-Apartheid) constitution, pleading with all South African artists not to entrust South African universities with their work.

In response, Wamuwi Mbao, a young art critic who supported the burning, gave a statement invoking the familiar jargon of the curatorial world, with a whiff of Foucault for good measure. Mbao complained of “an anachronistic panic compelled by the spectre of censorship that tends to invite underthinking. Art is about meaning and audience. So it might be useful, if we’re to think about the difficult question of what constitutes censorship, to understand that censorship involves particular dynamics of power and control (through withholding) of information that has a particular configuration in the world. Removing a work of art from a room because its meaning is unsatisfactory to its audience isn’t censorship. It’s merely changing the configuration of that art in the world. It’s still there even after being burnt.”[7]The removal of Art at UCT Interview in Litnet

The language of the arsonist mirrors the language of contemporary art curators.

Mbao lambasted Breytenbach for being boring with his plea, and alluded to Breytenbach having become a ”reactionary” simply for opposing the University’s plans to eliminate Afrikaans literature as a study — Afrikaans, a colonial offshoot of the Dutch language, happens to be the language Breytenbach writes his poems in. So is Mbao serious or just cajoling and bullying (with a touch of Foucault)?

Little regard there for the irony of how Breytenbach had been censored by the white supremacism of Apartheid when he stood trial for a poem that asked, in Afrikaans, how a certain police commissioner could finger the pudenda of his wife with the same hand that had murdered black children.[8]See JM Coetzee’s ”Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship” for commentary on trial against the poet

Perhaps Mbao’s admission of boredom reveals one key motivating factor behind iconoclastic pyromania in the world today: the boredom and frustration of an ascended middle class, the perfidious ennui that French maudit poets warned and warred against.

“Where they burn books, they will also ultimately burn people”- Heinrich Heine, 1821 (quoted by South African journalist Geoff Siffrin in response to the Capetown University art-bonfire.)

SA Arts writer Edward Tsumele denounced the Capetown burnings as a violation of democracy and artistic freedom. When asked if art can be decolonized he told the press ”Let the art prevail, colonial or not colonial. This is an expression of how certain artists interpreted what they saw at certain times in history. Let us as the public view everything” and he added ”What I resent is for people to be offended on my behalf, and therefore try to think for me as to what art I must view as an adult. I should be allowed to be offended on my own behalf, not have anyone else being offended for me.”[9]Lit Net Interview. 2016 Web. The notion of taking offense on behalf of another seems descriptive of neurotic positions assumed by censorious activists in both wealthy and poorer countries today.

The burning in Capetown foreshadowed what would happen a year later, in April 2017, across the Atlantic from Kassel’s quinquennial: when a group of mostly British artists rallied by Hannah Black put forth a petition demanding that the painting Open Casket, shown at the Whitney Biennial, be burnt as a punishment for the artist Dana Schutz’s appropriation of the historical subject matter of black oppression. The insistence by young artists on burning a painting as a form of progressive activism, their ignorance of history, and their ire when the word ”censorship” was used, recalled the horrors of book-burning as the true poet Heinrich Heine foresaw them in his native Germany. And once again, the censorious lot insisted that their demands should under no circumstance be be identified as censorship: using the logic of academic cultural theorists, it must be called something else.

These recent censorship scandals are, of course, not the responsibility of Minujín, whose work should not be obliged to reportage on anything that does not give the artist’s journey its necessary pleasure in creation. Perhaps Minujín finds more inspiration in the Afghan and Iranian censorship, in the censorship of conservatism and police states, in societies where intellectuals cannot live in easy denial of the life and death struggles as they do in the Berlin Hogeschule (where a poem in Spanish equates with sexual harassment). If the root cause of all this violence really is middle class boredom; if the hidden culprit really is a dangerous ennui that breeds this new censorship, then the exploration of those roots cannot possibly enliven the passion of an artist.

But it remains an ethical responsibility of self-titled arbiters and intellectuals of the art world to point to the censorship happening nearby. These events did not occur in Maoist China, Stalinist Russia or even under the very-recent Argentinean Junta that murdered and persecuted my people. When censorship occurs in front of the art-world intellectual, nearby in the spectrum of time and place, they must comment on it, and not only dig for the more estranged and foreign censorship of demised enemies.

The skeletons of history’s closets are finding much rhyme and resonance in today’s danse macabre of contemporary censorship. Rather than living up to their duty to repudiate it, such curators only invoke artistic freedom when it affects their stipends and budgets, as occurred recently when the Documenta team ran face-first into the wall of reaction, noticing the true attitudes of its German sponsors who punished the foreign curators for spending on Greeks. What the public intellectual Ulrich Beck cleverly called the ”Merkevellian” political consensus, insists that Greeks today need to be punished, spanked (Disziplinierung) not spoiled with more German gifts. In turn the truant curators who cheated on Kassel with a Greek whore were accused of ”corruption” and misspending for their Athenian adventure. Adam Szymchyk, the Polish curator of Documenta, has every right then to invoke ”artistic freedom”, but he could have done that more often in solidarity with artists around him.

Many curators prefer to live in denial of the prominence of new moralism and censorship in the mainstream art world. New censorship is not limited to the art and academic world, however; nor is it an exclusively right-wing extremist or ”Trumpian” phenomenon: thought-policing and information control is alive and well among its most respectable enforcers, who are liberals. One must only look at the campaigns by Silicon Valley to limit access to websites like AlterNet, and the current French president’s proposed measures to contain ”fake news.” Would an artist like Orson Welles ever have gotten his satirical works like War of the Worlds past the current regime of self-declared truth-tellers?

Minujín’s Parthenon II is a collaborative work. The creativity came from Minujín, but the informative and scholarly assistance came from a highly corporate bookfair and from the transnational team of curators who convene in Kassel and, more recently, in Athens. Curators rarely discuss it, with rare exceptions—such as when a queer-themed exhibition was shut down by the Brazilian right-wing government, among few cases of contemporary censorship denounced by E-Flux, the trade mag of contemporary curation. But curators are entirely aware of the boom in censorious activity, while they participate as enforcers or as passive spectators — and similar trends assail the literary field of ”creative writing”. Publication of literary writing in the 21st century resembles what happened to philosophy in the 20th century: academics write. Literary academia’s almost exclusive dominion is why we won’t be seeing new Nabokovs or Bukowskis coming out any time soon. What about a Nabokovian woman, you ask? A new Anais Nin, perhaps, even if she was a poseur with that flaky Henry Miller… Enough of greedy male literary lechers, time for a female sex-writer! Bring it on then. And no better place to seek out such female literary voices on eroticism than France–Mais voilá, la censure c’est en vogue à Paris …

French writer Sarah Chiche described the interaction that sparked her to draft a manifesto in Le Monde denouncing ”Neo-Victorian” and ”puritan” values: furious at her publisher who underlined sex scenes in her novel, insisting on removal, as today’s climate no longer accepts descriptions of hot gratuitous sex[10]Hadni, Dounia. ”Libération” ”Sarah Chiche: à torts des Raisons” Newspaper article Liberation Jan 2018 Web., since ”these days explicit sex is ‘not done’ in contemporary literature”. That and prohibition riled her to join novelist Catherine Millet (of The Sexual Life of Catherine M) and other women to draft the manifesto in defiance of the ”unanimity” prevalent in mainstream media.

Many female art curators figure among the 100 signatories listing their names and professions at the bottom of the letter that infuriated the blogosphere. The pamphlet, signed by 100 French female intellectuals, sought to reclaim feminism, at last denouncing censorship and anti-eroticism against the Egon Schiele paintings like Girl with Orange Stockings and Self Portrait Nude censored in poster form in the London tube. The heroinic letter ‘calling for ”the right to cause discomfort” repudiates the anti-Balthus campaign in passing, advocates artistic freedom and recognizes a right to gallantry, to creepiness and clumsy seduction.

The pamphlet was published in the midst of the hashtag media war about harassment. Most English-speaking publications misattributed the manifesto to its most famous signatory, actress Catherine DeNeuve, referring to ”Deneuve’s letter in Le Monde”. The actress was not the manifesto’s mastermind but, in a time when academics discuss ”the feminism of Beyoncé” it is unsurprising if young press lords of my generation, fresh out of grad-school (with a severe migraine from the cold absence of knowledge carved by their cold-hearted professors) take greater interest in celebrities than in writers or in intellectuals. Those ”feminists” (often male) among the press lords rather pretend the French female writers and intellectuals do not exist, and that only a movie actress’ statements need be addressed.

Many defenders of ”political correctness,” or as they like to call it ”civil discourse” will point out how today’s alleged censorship resembles a schoolmarm if compared to what happened in Stalinist gulags, or what happens today in police states around the world. They are right. But what has taken place recently in many cities of the world is a censorship suiting precisely these less heroic times, when institutions and curators buckle at the whims and petitions of people infinitely less frightening than a Stalin or a Videla. Today in the first-world societies both the villains and the ”activist”’ would-be heroes are just much more mediocre, apologetic, unimpressive, and wielding Blah as their most preeminent weapon. The censorship of a bored, frightened and consumerist society is ”censorship on demand”, responds to the needs of ratings, Pay-per-view and of pressure groups and focus-groups who act like irate customers. In capitalism, Customer is always right — and if the product offends, it better be cleansed.

The word curator implies a custodianship, as well as carrying the Latin meaning of quarantine or healing. Critics of Documenta’s mega-shows often point out the cathartic nature of Documenta as an attempt at healing history. If the custodians and protectors of art will not live up to their professional and ethical duties to protect art from moralistic violence, do we need them as authorities in the first place? Have these schoolmasters learned from history? As Chomsky’s anarchist dictum goes If ruling elites cannot legitimize their existence, it’s time to get rid of them.

| 1. | ↑ | Parthenon of Books Rises in Athens Sikiardi, Kerry. Jun 2017 article in Eu Greekreporter. Web. |

| 2. | ↑ | Nella Londro del sindaco Sadiq Khan le Opere Schiele Tornano |

| 3. | ↑ | Showing Balthus at the Met isn’t about Voyeurism, it’s about the Right to Unsettle Laura Elkin, article. Dec 2017, Frieze Magazine Web. |

| 4. | ↑ | Grenier, Elizabeth Berlin College To Remove Mural Poem Deemed ”Sexist” article, January 25 Deutsche Welle web |

| 5. | ↑ | Perhaps the problem in this kind of thinking was already exposed by John Coetzee in his essays ”Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship” when he wrote about feminist Catherine Mackinnon’s discourse on pornography. For thinkers like Mackinnon, use of the term ”censorship” is only appropriate if the political rationale of the censor is sympathetic or seems justified. |

| 6. | ↑ | List of art-works destroyed or removed at Capetown University in Ground Up Zimbabwean magazine Leaked document. Web |

| 7. | ↑ | The removal of Art at UCT Interview in Litnet |

| 8. | ↑ | See JM Coetzee’s ”Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship” for commentary on trial against the poet |

| 9. | ↑ | Lit Net Interview. 2016 Web. |

| 10. | ↑ | Hadni, Dounia. ”Libération” ”Sarah Chiche: à torts des Raisons” Newspaper article Liberation Jan 2018 Web. |