WAMUWI MBAO

We Are No Longer At Ease: A work of premature canonization?

#FeesMustFall was, contra Scott-Heron, a televised revolution. The protests that occupied the South African popular conscious between 2015 and 2017 played out on the news and on YouTube and in the media. Here: students running from the rubber bullet goons. There: students storming the grounds of the Union buildings. It was an easily mediated revolution, but not one whose meaning was as readily discernable as it may have initially seemed. Revolutions do not proceed at a pace that allows time for reflection. The best revolutions are over quickly. The revolution that lives long curdles and becomes rank with division, derision and disillusionment.

By now, the story of #FeesMustFall has sat for long enough to be conventionalized. The factory whistle has blown in the memory industries that sacralize events. Testimonies have been collected and set against dark backgrounds. The conferences have been organized, the colloquiums passed. The special issues are in the libraries. The archive is being built, and this is invaluable work. In South Africa, no area of public cultural life goes unlettered for long. Even while it was happening, the omnipresence of the camera was doing its best to transform the protests into a hemorrhaging of the democratic state. According to this narrative, #FeesMustFall and its concomitant protest bedfellows were harbingers of the great unraveling. Whether it succeeded or not seems to have been beside the point: the students forcefully brought something crucial to the forefront of the public conscious.

Does the centre still hold? #FeesMustFall was also the subject of many a thinkpiece even as it was happening. This was both good and bad: good because it demonstrated that there were people willing to do the hard public work of thinking through these events; bad because the thinkpiece is often the weapon of the neophiliac. At its worst, it is to the essay what a Big Mac patty is to a steak. It attempts to render the no-longer-immediate in a new and clever way. Thinkpieces are reports that don’t want you to think of them as reports. They attempt to be immersive, to make narrative out of disorder. They return to the scene. They contemplate. They examine what has passed in new light. And once you have enough of them, someone will inevitably suggest compiling them into a book.

On the face of it, this seems a reasonable enough proposition. Why not make available, in one digest, the disparate voicings, counter-narratives and interventions? In one sense, my skepticism is a distrust of the messianic drive that informs such projects. They are invariably phantasmal projections of nostalgia, behind which hides the reductive longing for cultural transparency. The logic of the telos does not equip us to understand the impermanent nature of our shifting phantasmagoria. I do not call it that because I don’t believe it happened, but because the intelligibility of the emergency is not apparent.

If you had told me a decade ago that that campuses like UCKAR where I studied, and Stellenbosch where I currently teach, could be brought to a halt, their business disrupted so fundamentally, it would have seemed as improbable as stopping a vast machine by chucking a toothpick into its workings. For the generation of students who, like me, graduated in the mid-2000s, the university’s imperfections scarcely seemed worth remarking on. It seemed only sensible, such was the style of our time, that we should throw ourselves at the feet of banks or of NSFAS, pleading for loans which we deferred year-on-year. The mood was quiet. We assumed that the university had our best interests at heart. We worked on our individual selves, convinced that this was the needful step towards the world we were about to enter. The university slogans said it all. This was where leaders learned. This is where we would be given the edge. We would graduate and earn some money and drive a Golf.

It seems deranged now to imagine that my generation had expected to have it so easy. We staggered from university, not to suburban high-income housing and jobs with corner offices in glass buildings, but to unemployment and tedious rentals and unmanageable debt. We were part of the organized social lie, perhaps the last willing participants in the wishful escapist phantasy offered up by the interlock between state, education and capital. The exposure of universities as needful of ideological refurbishment was difficult. It needn’t pass unremarked that the protestors were derided as anti-social by the university management-barons and by many of their fellow students. The students who were ignorant, and the students for whom #FeesMustFall was an aberration, would also benefit from what was achieved. The body of students who engaged in protest is smaller than the sensational press images make it seem, but soon it will be impossible to find anyone who did not support #FeesMustFall.

This last point might explain the necessity of We Are No Longer at Ease: The Struggle for #FeesMustFall. The editors, Wandile Ngcaweni and Busani Ngcaweni, have gathered together material dating back to early 2015. They attempt the onerous task of preserving events around the Fallist protests in their full vitality, before they detrite and become unusable. Such books always have the whiff of retreading about them: they recycle patches from other tapestries to form a quilt of convenience. This is not a slight: patchwork assemblies of varying textures can be compelling in spite of the obvious shortcomings.

So it proves with this book, a text that defiantly constellates thinkpieces, poems, long looks, short-impact opinion pieces and other kinds of written work by those who were around to witness the unmasking of South African universities as grotesque grow-houses of political conservatism. The best of these make the movement an object in memory with scale and depth and density, while the worst of these (deprived of the vital immediacy that renders agitprop thinking more flatteringly) make for moderately tiresome reading. To be sure, this book offers up a tumult of voices, among them students whose voices and images were often at the forefront of the revolution. There are also contributions from lecturers (perish the vague label “academic”), journalists and sundry public intellectuals.

Even bearing that in mind, the selection process for inclusion in this Primer on #FeesMustFall is wearisomely oblique. The editors present their effort as an attempt to “capture the voices of the student movement as part of our humble contribution to the archive.” We are also rather presumptuously told that this book “embraces different forms of expression and writing styles in a manner that brings authenticity to the stories being told.” The title is drawn from Chinua Achebe’s 1960 novel No Longer At Ease, but the link is unexplored by the editors in their introduction, and so seems to be one of mere convenience.

To Be Or Not To Be, No Longer At Ease

Njabulo S Ndebele

Keynote Address to the 40th African Literature Association Conference at the University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, 10th April 2014

By the second half of 1969 when “Obi Okonkwo and his girl firend Clara, knocked on the door of my awareness with the full reality of their imaginary lives” I was ready for them. Thus it came to be that I read and studied Achebe’s No Longer At Ease in the formal setting of a university syllabus in Lesotho. I found formal affirmation when and where I least expected it. A connection between my personal, social and school lives the necessity of which I only intuited suddenly occurred.

No Longer At Ease was the first full-length novel I read, which was written in English, by an African writer. It was my first sustained entry in English into an engrossingly imagined African world. It drew me in immediately with an intense imaginative intimacy such as I had never experienced before. My first literary lover, as I call it, No Longer At Ease, embraced me with firm, warm arms.

There was something in the reading of No Longer at Ease that was different from my reading of the autobiographies of Mphahlele, Hutchinson, Modisane, and Nkrumah. While the novel shared with the autobiographies an embracing sense of authenticity, the impact of its imaginative world worked without the kind of expository intent one senses running through the recalled and recreated life of autobiography.

In No Longer at Ease the drift of the world and some of its insidious moments came across in subtle ways. In the very first page of my treasured copy that cost me sixty South African cents in 1969 is an almost throwaway reference to “Some Civil Servants” in Lagos who “paid as much as ten shillings and sixpence to obtain a doctor’s certificate of illness for the day” so as not to miss the case of Obi Okonkwo on trial for corruption. How many of these equally corrupt (including their complicit doctors), were there in court to witness a trial in which their very own conduct was under scrutiny and that they seemed unaware of the irony in which they too were on trial, and that their own behaviour was as reprehensible as the accused’s whose public disrobing they had come to witness, and perhaps enjoy?

I remember the assignment topic: “Real tragedy is never resolved. It goes on hopelessly for ever. Conventional tragedy is too easy. The hero dies and we feel a purging of theemotions. A real tragedy takes place in a corner, in an untidy spot, to quote W.H. Auden. The rest of the world is unaware of it. Discuss.”

Obi Okonkwo’s perspective on tragedy may underscore the aesthetic conception of the novel that tells his story. In No Longer At Ease Achebe created a world without postured messages of self-justification, self-proclamation, or censure and reproach. Instead, it had something far more elemental in its social wisdom. He portrayed a self-validating, self-referential world with its strengths and foibles at a level of literary rendering I had not experienced before. Here was a world inwhich I felt I did not have to justify living in it, nor did I feel any pressure to abandon it for other worlds whose power over me demanded that I aspire towards them, away from my own. I belonged to Obi Okonkwo’s Umuofia, to his Lagos and its Ikoyi and to Clara’s Yaba.And it was not a romantic world, as Obi’s “mummy wagon” journey to Umuofia depicted. It could be as hilarious as it could be sad.

The imagined world of No Longer At Ease whirled on its own orbit in a vast universe. With cosmic indifference, that universe exerts influence on the human moral or ethical order. In that universe human beings are doomed to create ethical and moral markers with which to sustain their own order as well as navigate within it. Human beings have a large measure of responsibility for worlds they create. Within such responsibility, they take decisions that make or undo them.

Text reproduced here with kind permission of Professor Ndebele.

Confronted with what seems an admission of laissez-faire editorial input, a concerned reader might wonder if more care might have been taken. The same sense of haste that characterizes Adam Habib’s intriguing but flawed quasi-memoir Rebels and Rage can be glimpsed here: a sort of anxiety that everything must be said now or risk slipping into oblivion. How, when it’s all out there on the unforgetting internet? Is ‘authenticity’ all we’re looking for, and how do we go about verifying who has it? The authentic tends to have shallow roots, since what it privileges is proximity. Where were you when the teargas was thrown? Where were you when the riot police entered the building?

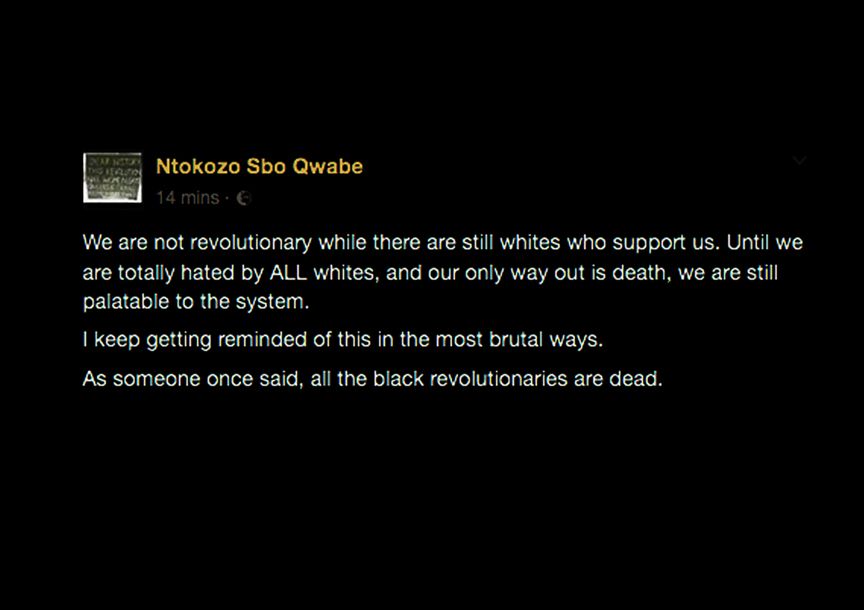

The collection is of mostly short pieces, and begins with Ntokozo Qwabe’s plangent I Am So Tired. It is a terse but affecting piece of writing whose titular refrain sloughs off the suffocating burden of white guilt.

“I am tired of white people not getting it and not being interested in getting it,”

he says in a manifesto that sits heavily in this collection, and renders the “Dear White People” essay that follows it obsolete.

Mcebo Dlamini’s sketching of the broad mechanics of the student protest enterprise is a useful throughway that covers a lot of ground, not all of it thoroughly enough. His rendering of events trots seamlessly through the history of the movement, with some pauses at vacant lot signifiers like ‘speak truth to power’ and “workers became students and students became workers” (5). Dlamini’s piece is detached in register – he sometimes lapses into the ‘mistakes were made’ cadences of a politico –but his is one of the more well-resolved pieces in this collection.

Some of the other pieces are exhibitions of gimcrack political blatancy (to be proud of using a word like ‘Kardashianism’ is to have bought into one’s own importance), bloated by rote recitals of historical detail that are heavy on facticity but light on meaning. But their inclusion is helpful for providing the coal against which the diamonds sparkle. Sisonke Msimang’s sinewy essay is a lighthouse of clarity. Discussing the ways in which a disingenuous understanding of ‘merit’ is deployed as discursive justification for excluding Black people, Msimang says,

In some ways it is an archetypal myth – one that can be seen everywhere in daily life. The myth of meritocracy was called upon in countless social media posts by white South African students frustrated that their ‘hard work’ would be jeopardized by the actions of the protesters.” (100)

An essay like Sarah Mokwebo’s too-brief “What Solidarity Looks Like”, meanwhile, fleshes out the implications of collective action:

As a Black woman, solidarity demanded of me, after seeing another black woman being inhumanely dragged into the back of a police van along with several other male comrades, to hand myself over and be arrested along with her, because she, like myself, was already vulnerable in this world. (93)

Hers as well as the writing of others are gathered under the banner of “intersectionality and feminist perspectives”, a labelling that consigns such perspectives to the periphery. These pieces attest to the ways womxn and LGBTQI individuals had to force their way in to a movement crowded with male voices. In this regard, it is somewhat of an editorial shortcoming that We Are No Longer at Ease is divided into four sections, with the various writings being pigeonholed according to the ideologies they are deemed to manifest, according to their methods of dissection, according to their broad styles or modes of inquiry. Here my first quibble emerges: many of the pieces express continuity with each other in ways that invalidate the rather disingenuous taxonomies. Although the editors and various contributors demur in rounded tones about the importance of womxn’s voices, the shaping of the anthology confines gendered thought to a separate category, which seems to defeat the point.

There is a paucity of commentary on the not-inconsiderable reservoir of documentary footage and visual representation, which garners only a desultory review and a cursory mention every now and then. This is a critical impoverishment, and one that points to the haste of the book’s assembly. That there were people in the movement who distrusted the media is a given: counter-cultural practitioners in 1960s San Francisco called it ‘media poisoning.’ But to read through such a distended collection (some of the pieces tread over the same ground) and meet no reflections on the various documentaries that are out in the public domain seems odd.

A more serious problem that occurs throughout the anthology can best be seen in Mcebo Dlamini’s essay. When he proposes that #FeesMustFall was of a piece with Soweto, Sharpeville, and the Women’s March to the Union buildings, he is of course correct, in one sense. But in another way, he and the other guilty parties are indulging in needless seen-before-ism, a phenomenon that reduces history to caricatural cliché. Comparisons might seem to confer legitimacy through contextualization, but they also choke off what is different. Every new event is not a repository for what already exists. What is needed is a more supple way of reading recent history that does not immediately root around for parallels in the bag of South African history.

Ultimately, I worry that this collection is a work of premature canonization. The effects and repercussions of #FeesMustFall are inestimable, and will stretch down the decades and past the artificial denouement these pioneering collections aim to establish. That We Are No Longer at Ease ends by trying to unpack what ‘free education” means is illustrative of the point. These closing essays are workmanlike, and they do the obvious job of narrativizing the facts and the figures into easily assimilated bites of meaning. But they’re an odd fit, even in this rather disjointed collection, hammering home what the other essays have cumulatively already confirmed: that Higher Education in South Africa is an insoluble problem. Familiar territory: the clear-if-complex problem and the open-ended resolution.

There is no reason to think that protests of the sort that characterized #FeesMustFall will not come again. The problems have not disappeared. There are students whose paths have been irrevocably altered by what happened. For their sake, a more complex unpacking that goes beyond the short attention span of the thinkpiece and the blog post is required. It would be difficult for anyone to do justice to the fullness of this emergency, and certainly to do so without reifying the fable of a previously unfragmented South African society. Many of us, when we are not being enjoined to buy into easy nostalgia, know that South Africa’s unity has always been at the expense of the have-nots. It’s an old tragedy. How it gets retold is the crucial thing.