ZAKES MDA

The La Traviata Affair – dispelling the ghosts of complicity

Author: Hilde Roos | Publisher: University of California Press 2018

I enjoyed this book. Immensely. This is an unusual thing to say for a book that is primarily not written for entertainment like a novel, but is a scholarly text based on academic research. I hope I will, among other tasks, highlight those aspects of it that made it a compelling read. It is important to start with this and get it out of the way.

My first encounter with the Eoan Group (eoan: of or relating to dawn) was in the pages of such popular magazines as Drum and Zonk in the 1950s and 1960s. Zonk, in particular, first published in 1949, focused on Black South African modernity (isimodeni, as it was then called), and used representations of the culture of African Americans (or Negroes, as they were called then in both the USA and South Africa, the kind of nomenclature that persists with older generation South Africans) as aspirational and a model for South African Black “progress.” The whole notion was highly influenced by the Harlem Renaissance, and exponents of that movement were often featured. The magazines used this depiction to sell an idealistic vision of the Black condition which was either at odds with the true condition of Blacks in South Africa or was unattainable to them.

Sophia Andrews (mezzo-soprano) sings Bloody Mary’s song ‘Bali Hai’ in Eoan’s 1968 production of South Pacific by Rodgers and Hammerstein. The Cape Town Municipal Orchestra is conducted by Joseph Manca. (3’55”) This bootleg recording was made during a performance in either the (now demolished) Alhambra Theatre in Cape Town or the Luxerama in Wynberg. The recording was later issued on a 7-inch LP by Feature Film Sound.

Thus, the appearance of Eoan dive and divi in their splendid gowns and cloaks spoke of advancement closer home. From the pictures one could not distinguish members of Eoan from American stars like Josephine Baker, Lena Horne or Marian Anderson who were the staple in the pages of such magazines.

And then I did not hear of Eoan Group for many years, until in 2013 when I saw An Inconsolable Memory, a poignant documentary film on the group produced and directed by philosopher Aryan Kaganof at the Stellenbosch Institute of Advanced Study. The group was in existence all along, from the year it started in 1933 with elocution classes to their performances of Martin Shaw’s cantata, The Redeemer, in 1946 (by 1947 Eoan had become a movement, with 21 branches in the Peninsula and one in Port Elizabeth) to their final recital of arias by various opera composers in 1979. Eoan is extant, but today it only functions as a dance company and ballet school. I think the group fell out of sight and therefore out of mind for those of us not residing in Cape Town after it became politically incorrect to lionize it in glossy magazines.

Roos’ book is on the history and political economy of staging “opera in the age apartheid,” with the focus on Giuseppe Verdi’s three-act opera, La Traviata, first staged by Eoan Group in March 1956 at the Cape Town City Hall as their first production of a full opera. The group has since staged many other works ranging from cantatas, oratorios to full operas but La Traviata remains their crowning glory.

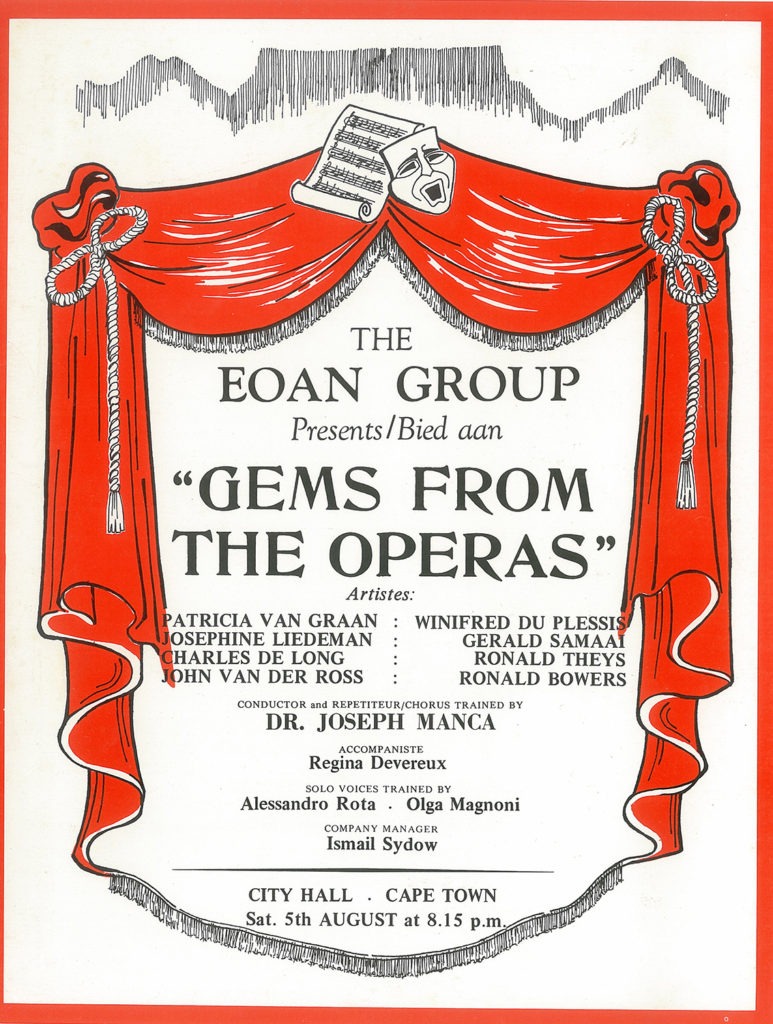

That first production was produced by Italian émigré Alessandro Rota with Eoan’s artistic director Joseph Manca as the conductor.

Manca was a South African of Italian descent, much given to exaggeration about Eoan’s achievements. For instance, he claimed this was “the first Coloured performance in the world of a complete Italian opera.” This of course is what today would be called hype. There had already been performances of European opera, including Italian, by African American companies, including in 1873 the Coloured American Opera Company in Washington DC which staged Alessandro Scarlatti’s comic opera Il trionfo dell’onore; in 1900 the Theodore Drury Grand Opera Company produced with an all African American cast a number of operas, including Italian ones such as Verdi’s Aida and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci. The Eoan Group, however, had more staying power than any of these efforts, but it was not the first.

Manca, a man of superlatives, wrote of the presentation of La Traviata as “the dawn of a new era for the Coloured people in their striving for the higher things of life.”

Roos correctly observes that today such attitudes would be read as not only naïve but patronizing and politically compromised. She writes that such statements, and those of reviewers that were in a similar vein, endorsed “apartheid themes of Western cultural superiority, cultural homogeneity, and the ‘civilizing’ purposes of apartheid’s separate (read racial) cultural development.” Indeed, for this very reason one of the greatest opponents of the group was Alex La Guma, then chairman of the South African Coloured People’s Organisation. Many of us remember him in later years as a South African Communist Party (SACP) leader and African National Congress (ANC) representative in the Caribbean who wrote iconic novels and short stories.

Though he praised the group’s work as an illustration that Coloured people could excel in the realm of culture given the opportunity, he vehemently criticized the fact that the group had a special performance for “Europeans Only” (South African Whites used to call themselves Europeans) where cabinet ministers and members of parliament were invited. He was also unhappy that the group was funded through the Coloured Affairs Department, an apartheid structure for the governance of Coloured people. He concluded that Eoan therefore supported apartheid. Pamphlets were distributed in the streets accusing the group of being befouled by an apartheid atmosphere.

Another creative titan from within the Coloured community who wrote scathingly of the Eoan Group was Adam Small, one of the intellectual leaders of the Black Consciousness movement. This shows that culture had been a terrain of struggle long before Trevor Huddleston and the international anti-apartheid movement he led convinced the United Nations to impose a blanket ban on all international acts performing in South Africa and all South African acts performing abroad.

Joseph Gabriels (tenor) sings the Duke of Mantua’s aria ‘Ella mi fu rapita’ from Eoan’s 1960 production of Rigoletto by Giuseppi Verdi. The Cape Town Municipal Orchestra is conducted by Joseph Manca. 5’11” This bootleg recording was made during a live performance in the Cape Town City Hall. In 2000 the recording was restored by GSE Recordings in Claremont and issued as a commercial CD.

You might remember how this culminated in the boycott of Paul Simon’s Graceland Tour of the United Kingdom and the United States which saw South African artists divided – brother/sister pitted against sister/brother – including artists such as Jonas Gwangwa who wanted the boycott to be enforced strictly and Hugh Masekela who wanted it to be relaxed when the performances benefitted Black South Africans as an oppressed people. It was not unusual to have Gwangwa and Huddleston, both close friends of Masekela and the latter his mentor, demonstrate outside a venue in London while Masekela blew his trumpet with Paul Simon, Miriam Makeba and Stimela inside. Like those who were to defy the cultural boycott during this period of our political struggle, the artists of Eoan felt they were being victimized by apartheid on one hand and by the anti-apartheid establishment on the other hand.

The book presents this conflict within the Coloured community, and between the Coloured community and the apartheid establishment, quite early in the Introduction, with the protagonists and the antagonists neatly drawn out, creating an anticipation the reader hopes will be fulfilled in later chapters. This is part of what makes the book a compelling read, for we hope this will lead us to some climactic confrontation and then to some form of resolution. This conflict is exacerbated by the conservative elements within the community who view the very engagement with European cultural modes as betrayal.

Sadly, this attitude prevails in some quarters even today. South Africa punches far above its weight in the world of opera, and has produced great sopranos such as Pumeza Matshikiza who plies her trade in some of the top opera venues in Europe and Pretty Yende who often is an attraction at La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera in New York, bass-baritones Musa Ngqungwana and Patrick Tikolo who also enjoy some international recognition; and of course the rising opera star Noluvuyiso Mpofu – all thanks to the South African choral music tradition and formal education institutions such as the South African College of Music at the University of Cape Town. These stars are celebrated by a small sector of South African enthusiasts, viewed with indifference by another sector, and indeed despised by the third sector that has an essentialist understanding of culture and views participation in European classics and neo-classics as unAfrican.

Another anticipation that the Introduction creates in me, and I hoped would be fulfilled as I read on, emanates from the parallels Roos beautifully elicits between Eoan’s narrative and that of Violetta, La Traviata’s tragic protagonist, “the fallen woman”, Violetta Valery. Violetta the courtesan other and Eoan the Coloured other, a theme of otherness that runs through the work. Even the group’s own conductor, Joseph Manca, deals with its members in a paternalistic manner as illiterates who sing opera and refers to them as his musical children.

We expect to follow Eoan’s story through the framing narrative arc of Violetta’s rise and fall. We learn that both Eoan and Violetta were enchanted by an utopian world for which they sacrificed everything, both were forced by figures of authority to give up that world, both were publicly scorned and humiliated, and both had their downfall hastened as a result of their choices. Framing an historical chronicle and political economy analysis within a fictional narrative promised to be a very engaging method of metaphorizing the rise and downfall of Eoan. Unfortunately, the author merely tantalizes but does not follow through with this. She does not make direct references in the text but obliquely makes them paratextually at the opening of each chapter with a quotation from La Traviata’s characters. These epigraphs are sometimes quite poignant, as in Violetta’s “Farewell, happy dreams of bygone days…” But somehow the extended metaphor is lost. However, this is not a flaw to write home about. Take it as the quibbling of an aging storyteller, though I do think this wonderful book would have been more enthralling that way.

Throughout this narration the notion of “Coloured identity” is central. Roos notes that the term “Coloured” has been used since the nineteenth century to refer to people of darker complexion who were not European and yet did not belong to any of the Black African “tribes” of southern Africa. As an aside, I would like to give my own piece of advice here. “Tribe” as a descriptor of African ethnic groups is anathema in the vocabulary of progressive scholars because it promotes misleading stereotypes and a myth of primitive African timelessness. Read Chris Lowe’s article on the subject.

Coloureds have diverse heritages ranging from immigrants and slaves from Malay, Indonesia, Madagascar, China, and indigenous people such as the San, Khoikhoi, the Griqua to White slave masters of European origins. Coloured identity therefore is not dependent on skin colour.

Roos notes that some of the Coloured folk have aspired to assimilate into the “superior European culture”, which might explain Eoan’s own aspirations. But I would like to point out the irony that is often ignored: the Coloured culture in all its varieties has made a great contribution to South African White culture, ranging from the cuisine that some of their ancestors brought from Malay and Indonesia, syncretizing it with Cape Dutch cuisine, to the language itself that the slaves invented as their creole for communication among themselves, which the Dutch and French descendants adopted as their own and called it Afrikaans. The Bo-Kaap organic scholar, Achmat Davids, made extensive research on the origins and development of Afrikaans, demonstrating that the first written Afrikaans was in the Arab script that Islamic Cape-Malay slaves used.

Eoan cooperated and submitted to White domination both for their survival and because of their aspiration to assimilate into the “higher culture” to which they were entitled. There was also the desire for upliftment to the levels of acceptability in a White world that had always marginalized them – the world that was fascinated by them and yet loathed them.

As I read the Roos book, I am struck by the lack of acknowledgement by classical music enthusiasts and academics of Eoan’s great contribution to the development of opera in South Africa. Eoan was ahead by decades of White opera production organizations, including CAPAB (Cape Performing Arts Board) which was established much later in 1963 as part of the government founded and funded Performing Arts Councils (PAC) for each of the four provinces. The PACs were for Whites only. The unpaid artists on Eoan, the first group of this kind to consistently produce opera, outdid the highly paid performers of CAPAB for some time in the early years.

Another irony was that the Eoan Group was used by the government to illustrate the success of apartheid. In the early years of its foundation (remember, it was founded in 1933; in 2019 it turned 86 years old) Eoan depended on wealthy citizens and government officials for donations. In 1940 for the first time the group received some government funding. Joseph Manca joined the group in 1943 as choral conductor, specialising in cantatas and oratorios. Their music programme included jazz, though some despised it as a “pathetic American Negro art.” Remember that Eoan’s unique selling point was based on the phenomenon of working-class singers who performed “high art”.

Roos notes: “As the history of apartheid unfolded, the two musical genres of classical and jazz became increasingly informed by a language that situated them on either side of the political divide.” What this means, from my own observation and therefore not elaborated in the book, is that jazz had possibilities of being more radical in its political expression, while classical music remained conservative. Jazz was dynamic and allowed for new content and could therefore serve as an effective weapon against “the system.” Classical music on the other hand was static especially in the manner that Eoan staged it and had no room for new content. La Traviata, for instance, had to be faithful to the norms, content, language and performance style of the 1850s when it was composed. It was only later in our history that the classics and neo-classics were subverted in Cape Town (once again Cape Town playing a pioneering role) and adapted to speak about life in the townships. For instance, Georges Bizet’s Carmen was transplanted in a Cape Town township as uCarmen eKhayelitsha (2005). Of course, such subversive adaptations wouldn’t have been contemplated by Eoan since the aspiration was to European purity. Instead they opted for verisimo – a post-Romantic operatic style; the Italian version of naturalism.

Before venturing into a full Italian opera Manca conducted newly composed works from England and early 20th century compositions that are no longer extant. Handel’s oratorios, and Mendelssohn’s and Bach’s, became part of regular repertoire. Handel’s The Messiah has been a staple of African choirs in the Cape Colony from the late 1800s. Manca was very methodical, and aimed to ease his charges into fully-fledged opera first by staging cantatas and oratorios, and then their first comic operetta, Alfred J. Silver’s A Slave in Araby.

After 1948 the National Party brought drastic changes affecting everyone.

Apartheid laws that were passed soon after the takeover included the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, Immorality Act Amendment (prohibiting sexual relations between Black and White or miscegenation), the Group Areas Act (assigning different residential and business areas for different “races” as defined by apartheid law), Population Registration Act (forcing each South African to be registered as a member of a specific racial group), Separate Amenities Act (designating public spaces for different racial groups; what became known as petty apartheid) This new order affected Eoan negatively as the group needed to have separate entrances for different racial groups, and separate seating. They needed to apply for permit to have White audiences in the same venue and had to provide separate entrances and separate seating for the Whites. Eoan obeyed. Under Manca the group opted to stay away from politics.

Eoan decided to accept subsidy from the National Party government, causing quite a storm.

1952 was the 300th anniversary of the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck in the Cape and the National Party commemorated the event throughout the country. Most Coloured communities boycotted these celebrations, including the government funded Eoan Group. But not everyone in the group agreed with this decision. There was a section that opposed the boycott because they wanted to ingratiate themselves to the ruling White establishment and those who feared the loss of the annual government grant. Among those who advanced the boycott position there were the principled one who were opposed to celebrate 300 years of their own oppression, and those who opposed participation on racist grounds; hatred of other Africans – they didn’t want to see Coloured little girls, as they said, dancing “like Zulus and Kaffirs.”

These are contradictions that are yet to be resolved in the Coloured communities. Some Coloured people, as an in-between group, regarded themselves as closer to White than to African, and therefore as more “civilized”. They were yearning for the elusive White acceptance. There was, however, a more progressive trend, a political one that recognized and celebrated the Coloured’s African identity and even named the political movement that looked after Coloured interests the African People’s Organization.

The first chapter hardly touches on La Traviata. It sets the scene for the big event – the La Traviata Affair! It gives us the backstory; the origins, the historical background, and the political contestations. The first performance of Verdi’s La Traviata by the group was in March 1956 to rave reviews. It was Eoan’s first performance of a full-length Italian opera, and it had a great impact on the future direction of Eoan.

Manca continued being dismissive of politics and its impact on the arts, which was quite amazing because his members were affected and had to negotiate their lives in a maze of apartheid laws. Politics was a very disruptive influence on the group. For instance, on their 1965 tour of South Africa and their second visit to Johannesburg they were refused permission to perform for Africans and Coloured and could only perform for Whites at the Civic Theatre – a far-cry from an earlier tour of Johannesburg when Blacks were allowed to attend at an all-White venue to see the group, as long as seating was separate. Their Carmen received bad press, while the group received an all-round condemnation for bowing to apartheid. In fact, politics was the downfall of Eoan.

Over the years the Eoan Group returned to La Traviata repeatedly. The initial success encouraged them to stage other full operas such as Rigoletto, Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Cavalleria Rusticana, La Boheme, Madama Butterfly, Carmen.

1957 to 1963 was the most productive period for the group not only in opera but in theatre and dance. They also performed American musicals such as Oklahoma! South Pacific, and Carmen Jones. they toured Port Elizabeth and Durban in addition to Johannesburg.

It is poignant that Verdi’s La Traviata was their first full opera in 1956 and their last in 1975, both with May Abrahamse as Violetta.

The first section is the recitative, Teneste la promessa’ which flows directly into the aria ‘Addio del passato’. The numbers are from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera La Traviata, Act 3. This is Violetta’s last aria in the opera, at the end of it she dies. Brittany Smith is accompanied here by Albert Combrink on piano. Brittany’s connection with Eoan is via her uncle, Isak Hendricks who used to be a singer with Eoan. When asked to perform at the book launch she replied “I am available and very honored to be a part of this. My uncle was once part of the Eoan group and he recently passed on, so there is great significance for me.”

The slow decline of Eoan from 1964 onwards happened because of limitations in accessing performing venues because of the Group Areas Act. Manca continued with his superlatives without ever acknowledging that apartheid was devastating to the group and affected artistic standards. Lack of adequate funding continued to be the bane of the group. They had to enforce apartheid in order to get government funding. The bad publicity they were receiving for performing for apartheid officials was gradually killing the group.

Accepting government funding forced Eoan to participate in government events, for instance the 1966 Republic Festival – further tarnishing their reputation among Coloured people. The group was fenced in by apartheid, and was isolated with no benchmarks to speak of, except in 1975 when they toured Italy and the United Kingdom.

Eoan artists continued to work unpaid, they were dependent on their day jobs. Quite an irony for a group that claimed to work for the upliftment the Coloured people. Many people saw this as exploitation instead. But for most of the members this was a labour of love. Only those who were teachers to other members of the group got some stipend. Otherwise there was very little music education except the few who had singing lessons from opera teachers of the University of Cape Town College of Music.

Roos’ book has quite a few intriguing anecdotes. My favourite is the curse of Rigoletto – the story of the famous Eoan baritone, Lionel Fourie (a tailor in his day job, and later a teacher) who made his mark singing the role of Rigoletto, receiving rave reviews in the press. He died unexpectedly in 1963. He is remembered as having vowed before his death that “no one will wear my cloak”, by which he meant none of the other singers would sing the role of Rigoletto after him. Eoan struggled to perform Rigoletto after that. A performance had to be cancelled when principal baritone, Robert Trussell, suddenly died in 1969. When Rigoletto was performed again two years later principal singers claimed that they saw a second Rigoletto, ghostly in form, roaming the stage. They had to burn Fourie’s cloak to dispel the ghost after that.

The most successful Eoan singer was Joseph Gabriels who carved a career abroad, and even sang at the New York Metropolitan Opera – no mean feat those days.

Roos does not only look at the political economy of performance in apartheid South Africa, but also touches on the aesthetics of the works performed. She writes of a patronizing and condescending attitude of White critics who rarely spoke of artistic merit but were just in awe that Coloured folks were singing Italian opera.

In my view what accelerated the demise of Eoan was the advent of the Black Consciousness movement. Roos’ book does touch on the impact of Black Consciousness but does not discuss it as a significant factor in the radicalization on Eoan members and indeed Eoan opponents.

During the political lull inside South Africa after the banning of the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania no internal protest was discernible. This was broken in the early 1970s when the philosophy of Black Consciousness (BC) began to take root throughout South Africa – perhaps as early as 1968 when the all-Black South African Students Organisation (SASO) broke away from the predominantly White National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). What was different about BC from earlier movements was that it defined Blacks as comprising Indians, Coloureds and Africans, and its leaders came from those three groups. This was a new worldview altogether. Even when the ANC finally accepted Coloured and Indian members it was initially through their own organizations such as the Natal Indian Congress, the Transvaal Indian Congress and the South African Coloured People’s Organisation – recognizing them as blocs.

Black Consciousness aimed to obliterate apartheid boundaries and conflated all those oppressed by apartheid as Black. This outlook radicalized a great number of Coloured youths who actively campaigned against apartheid structures such as the Performing Arts Councils (read CAPAB in the Cape) and Eoan. Black Consciousness had a profound impact on culture because it was the first political movement that not only saw culture as the site of struggle, but as a weapon as well. It was both a political and a cultural movement and did not hold mass political rallies but effected its political programmes through cultural performances and exhibits.

Eoan was caught between two powerful forces, the apartheid structures on one hand and the revolutionary liberation movement on the other. The apartheid regime had infiltrated the group so much that the Department of Coloured Affairs had its members serve on Eoan’s board, and Eoan had no choice but to participate in the 10th anniversary celebrations of the Republic, sealing its fate as an apartheid structure.

By 1975 Nico Malan had opened its doors to all “races” with strict conditions as to entrances and seating (only in 1980 were Blacks allowed at the Nico Malan unconditionally) as did all other sectors of CAPAB. However Black people (Black Consciousness definition) boycotted all such structures, just as they boycotted the radio and television services of the South African Broadcasting Corporation. Eoan performed at the Nico Malan only once, but that was enough to reinforce their branding as an apartheid organization. To add to their woes SACOS – the South African Council of Sport – recognised by the anti-apartheid movement as its domestic wing, banned Eoan, a stigma that it carried into the future. Some of the group’s members joined CAPAB.

The decline of Eoan was not helped by Manca’s resignation in 1977 after 34 years with the group and of Eoan’s voice trainer and producer, Alessandro Rota in 1980.

I liked Roos’ narrative style and lucid prose. Her research is meticulous – thanks to the captive vaults of the Eoan Group Archive. Even the gaps or “discontinuities” that Roos mentions at some stage were not apparent to a reader like me.

It has not been our intention to infringe any copyright. In the event that we have made an infringement of a copyright will the holder of the copyright please contact us at roosh@sun.ac.za