PERCY MABANDU

The Unfinished De-colonial Work of Malombo

“music of the day before yesterday, for the people of the day after tomorrow”.

In the spring of 1964, black South Africa was in a bad state. The people found themselves blue, battered and bruised in the grips of high apartheid. For one, in June of that year, the Rivonia treason trial concluded with Nelson Mandela and other leaders sentenced to jail, for life. The move by the state dashed all confidence in organised resistance, and hopes for eminent freedom.

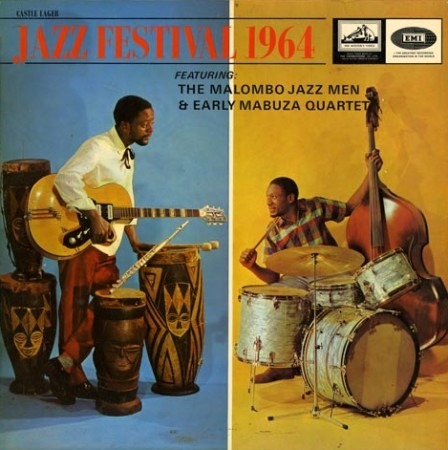

However, the marked dearth of activism in organised resistance politics, would be switched for birth pangs of a new awakening. Jazz music and other creative cultural activities rose to fill the void. On the 26th September, 1964 a gathering of over 40,000 jazz lovers in Soweto, Orlando Stadium would witness the triumph of ‘Malombo music’ pointing out a path to pride and people power. The Castle Lager Jazz Festival, organised by Union Artists, became something more than a regular musical event.

As the liner notes of the compilation record of the festival put it, “Malombo Jazz Men led by Philip Tabane, caused a great stir among the crowd. ‘Primitive’, yet sophisticated, it is a simple and soulful music.” Rooted in a melange of musical traditions, of cultures of the Limpopo – the Xi-Venda and SePedi – Malombo Jazz Men’s music on that day, sparked and awakened a hopeful self-regard among the people. Joy and revelry took on a defiant political tenor.

The band was built on a trio line-up of Abbey Cindi’s flute, Philip Tabane’s guitar and Julian Bahula’s Malombo drums. While Cindi whistle-washed his flute’s melody over the music’s propulsive step, stagger and scratching scamper, weaving lively lines in and through the rumbles and frets of Tabane’s Gibson. It was from inside the oom-boom-ba-boom of Bahula’s drumming that Malombo discharged its healing charm. The band’s choice to use cow-hide drums as opposed to a modern drum kit, is a central defining feature of Malombo’s mission and symbolic force.

The word Malombo is a xi-Venda equivalent to the Se-Sotho word, Malopo. They both refer to the drum and dance performance rituals of traditional healers – healers dancing and daring the earth to give them just the right kind of vibration. These rituals are governed by a sustained pulse and beat that goes: aah-boo-ku, aah-boo-ku, aah-boo-ku to open up portals to other realms. of perceiving and being. Malombo Jazz Men and other bands that followed in their wake, invoked the power of the ritual of Malopo and other African ceremonial drumming musics in their performance – this to code what Argentine semiotician, Walter Mignolo calls a ‘decolonial option’ for South Africa’s burgeoning jazz scene.

Mignolo proposes the decolonial option as a logical fruit of epistemic disobedience or an act of delinking from the modern-colonial matrix of power – which encapsulates the absolute hegemonic dominance of the west on culture, economy and thought. Mingolo further explains that, “delinking is necessary because there is no way out of the ‘coloniality of power’ from within Western (Greek and Latin) categories of thought. Consequently, de-linking implies epistemic disobedience rather than the constant search for “newness” (Mignolo, 2011) [1]Mignolo, W. 2011. Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World. Download here:

Malombo music manages, with virtuoso improvisation, to register an invocation of alternative histories – a decolonial option in creative praxis. Malombo music gives us a potent example of epistemic disobedience by delinking with the notion that jazz music, for instance is America’s classical music; a hegemonic notion championed by musicians and writers like Grover Sales who actually published a book of the same title. The phrase ‘jazz is America’s classical music’ appropriates this syncretic musical form into a Euro-American “colonial matrix of power.” It implicates Jazz music as north U.S. America’s version of a European cultural form. Hence its appearance elsewhere (like in South Africa), would only serve as evidence of Euro-America’s global cultural dominance.

Malombo by eschewing the dominant sonic tropes of Hard-Bop, a popular jazz sub-genre of the era, points towards other understandings of what jazz can be: a democratic musical possibility of exchanges across the “Black Atlantic” and beyond – here we share Paul Gilroy’s observation about Jazz, as a unique culture that emerges from contact across African, American, European, and Caribbean civilisations since the advent of global trade.

Consequently, Malombo embodies acts of epistemic disobedience which Mignolo says,

“takes us to a different place, to a different “beginning” (not in Greece), but in the responses to the “conquest and colonization” of America and the massive trade of enslaved Africans, to spatial sites of struggles and [collective] building rather than to a new temporality within the same space (from Greece, to Rome, to Paris, to London, to Washington DC). It is necessary to extricate oneself from the linkages between rationality/modernity and coloniality, first of all, and definitely from all power which is not constituted by free decisions made by free people (Mignolo, 2011)

In this way, Malombo Jazz Men on that fateful September day in Soweto, performed a grand invocation, pointing out a way of “de-linking” from the dominant aesthetic formulation of the musics we call jazz as it was, coming out of north America. They did this by embracing an African locality and subjectivities as their open center.

Original Malombo drummer, Julian Bahula remembers the band’s breakthrough with proud clarity: “We were very confident because our music was unique, not an imitation, and the three of us were like branches of the same tree. We had a similar sense of the sound we wanted to produce and there was chemistry on stage. The atmosphere was electrifying. Those who were there felt like it was the country’s freedom day.”

The sense of freedom Malombo inspired in the people, foreshadowed the spirit of the politics of pride that was on the horizon. The Black Consciousness movement, which would fill the gap left by the outlawed political organisations, reflected the self love and pride invoked by Malombo music.

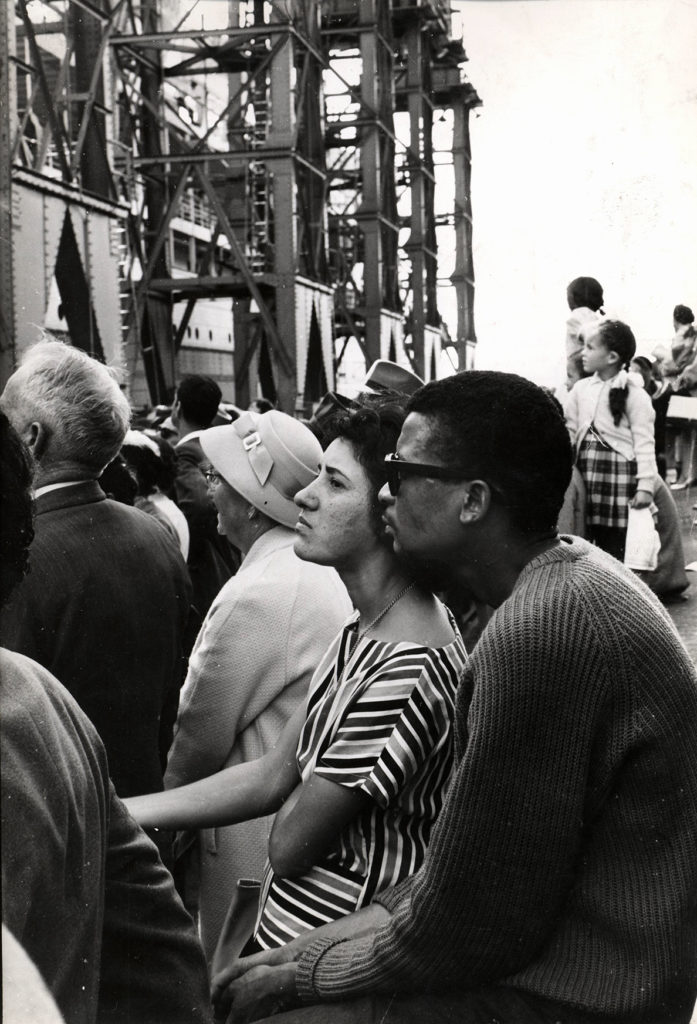

Four years after that fateful day in Soweto, in 1968, pianist Dollar Brand was returning home from a period of self imposed exile in New York. It was a pilgrim’s prodigal return that would culminate in him embracing Islam and changing his name to Abdullah Ibrahim. The searching pianist would mark his return with a series of columns in the Cape Herald (a local paper aimed at the coloured community). The column, titled The World of Dollar became the rising piano star’s soap box. Ibrahim “accused South African musicians of being too interested in merely imitating Americans and Europeans…” he charged that in fact, “they should, instead explore their own musical roots, the sacred and the beautiful music that grew in the African soil,” as John Edwin Mason writes in his study of Ibrahim’s 1974 record, Mannenberg. Mason relates how Ibrahim argued that, “coloured people who were ashamed of their folk traditions – ‘the doekums and the Coons’ – were, by extension, ashamed of themselves. He urged them to see their culture and themselves through his eyes. If they did, they would see that they were all beautiful.”

In his new awakening, Ibrahim was discovering a power that Malombo Jazz Men had tapped into a few years earlier; and to great success. The inspired pianist called on his peers to immerse themselves in “the entire musical universe of Coloureds and Africans: the jazz of Kippie Moeketsi, the ghoema beat and minstrel tunes of the Coon Carnival, Shangaan, and Venda, and Pedi folk songs, the Malay choirs of Cape Town’s mixed-race Muslims.

In truth, while Ibrahim’s rhetoric had a national sweep, he was really addressing himself specifically to the Cape coloured community. His charges would have been out of turn in the north of the country, four years after Malombo’s 1964 breakthrough.

Malombo Jazz Men and performances had taken on displays of African virtuosity as a sublime measure for the humanity of the oppressed. The triumph of Malombo music took on great decolonial symbolism. Malombo marshalled the power of vernacular identity with creative heroism, and shored up a modern musical idiom rooted in indigenous traditions as an intellectual compass and touchstone for what real freedom should look like.

Drums are the central embodiment of Malombo music’s decolonial praxis. They sketch a shared vision of freedom in the key of working people’s life and dreams. It is the drums that give Malombo music its symbolic force and its Pan-African vibe. It is the drum dynamic that embodies the music’s democratic register.

Among a lively league of notable drummers who’ve inherited the music, composer and academic, Sello Galane has pursued and expanded the form along with other variants created by the people of the greater Limpopo. Galane writes and performs contemporary music inspired and informed by Kiba, a traditional communal ritual music of the BaPedi. Kiba like other traditional forms, Dinaka, Makgagasa and Malopo or Malombo itself, are governed by a system of drumming that sets them apart.

In his album Free Kiba in Concert, Galane performs an exploration that pushes Kiba into its contemporary possibilities like jazz; just as Tabane, Bahula and Cindy had originally done with Malombo. Galane performs an illustrative medley, Fegolla Sa Borala medly Sebodu sa Mmashela, that explains Kiba’s drum dynamic.

The performance is based on the three types of drums. A big drum called Sekgokolo, a middle sized drum called Kgalapedi and a set two smaller drums called Matikwane. To explain how these drums work, Galane devises a metaphor of a family unit to illustrate the drumming system’s democratic dynamic. Galane sets up Sekgokolo as the father drum. It maintains and pounds a steady pulse and bass line. The middle sized drum, Kgalapedi he designates to the role of the mother drum. It is the main source of the musics’ lyrical flow and melodic direction. The twin drums, Matikwane accents off of what the two larger drums are doing. In this way you have the mother drums imparting the values of the household, which the children reflect and take cue from. The stability of their unit is kept by the steady rhythm provided by a reliable father.

The four-drum system can be read to speak to a larger social metaphor of the people and their interaction with each other and the state. It is in this way that the music, as a site of knowledge production, best embodies and illustrates Mignolo’s decolonial option, which would proffer the argument that Malombo is not a new paradigm or mode of critical thought. Rather, Malombo is a way, option, standpoint, analytic, project, practice, and praxis.

Even at the height of their success, Philip Tabane and Gabriel ‘Mabi’ Thobejane understood this. They were bent on epistemic disobedience with an unwavering fidelity to their Pan African subjectivities. In May 2018 following Tabane’s passing, pianist Darius Brubeck and his sister Cathy recalled in an interview, Malombo’s time in the New York scene, during their historic tour of the US; a notable moment in the history of the music. Tabane and Thobejane insisted on living their lives as though they were still on African soil.

Malombo’s tour of the US in 1977 was organised by Peter Davidson the band’s manager, working with Cathy Brubeck. This was the version of Malombo that comprised drummer Thobejane, Tabane on guitar and a 19-year-old Bheki Mseleku on piano. The tour included the historic date at Carnegie Hall as part of that year’s ‘Newport Jazz Festival’, New York. Davidson and Cathy Brubeck also managed to arrange for Malombo to play during halftime at an exhibition soccer match between the original New York Cosmos and Benfica. This gig was important because on the pitch that day were Jomo Sono, a recent South African addition to the New York team, the singular Brazilian soccer star Pele, along with Eusébio da Silva Ferreira – the Mozambican player, considered the greatest African footballer in the history of the sport.

Tabane and Thobejane had to rise to the occasion. Their appearance on the pitch that day was nothing short of spectacular. They had a dramatic impact, especially when they strode across the field in ‘tribal’ regalia and entered the members’ enclosure with Thobejane presenting himself as a ‘chief’ and ambassador. Tabane just stayed cool and went with the flow,” Brubeck recalled in an interview. The Malombo trio had actually opted to not check into a hotel but stay with the Brubecks:

“They shared our home in very urban Brooklyn, New York. Our neighbours were astonished at seeing a live chicken slaughtered, plucked and braaied in the backyard. It was even remarkable that Tabane and Thobejane found someone in Manhattan to sell them a live chicken.”

says Brubeck who saw the incident as ‘a metaphor for what they communicated in performance; something mysterious, unique and challenging.’

In the days following the death of guitarist and Malombo pioneer Philip Malombo Tabane early in 2018, many in the media were asking if his death marked the end of Malombo music.

The guitarist’s son, Thabang Tabane recently released his debut solo record, Majale. The ten track album put the music world on notice, that the music we call Malombo is live and well. The record was in fact the second release in the tradition by a new generation of musicians. In 2017 guitarist, Sibusile Xaba released a double album titled Open Letter To Adoniah, Unlearning which signaled the arrival of a new generation of Malombo inspired creative musicians.

They are stepping into a stream that began in the 1950s. Way before Malombo split into streams in 1966. Seeing Tabane partnering with Thobejane who took over the percussion and drums from Julian Bahula and started campaigning as The Malombo Jazz Men. Bahula continued as The Malombo Jazz Makers with Cindi on Flute and Penny Whistle. They took on Lucky Ranku who replaced Tabane on guitar.

Later in 1969, poet, painter and drummer, Lefifi Tladi led the formation of a new offshoot that included Rantobeng Mokou on vibraphone, Gilbert Mabale on saxophone and Laurence Moloisi on guitar. They called themselves Malombo Jazz Messengers but would later change their name to Dashiki on the advice of Bahula. Later, Bahula would himself continue the musical tradition in exile with formations like Jabula.

Today, more musicians like Galana have taken on the tradition in their wake. Tlokwe Sehume and Medu too have established themselves an institution. As Sehume often says, “this is the music of the day before yesterday, for the people of the day after tomorrow”. Its decolonial thrust remains unfinished until uhuru.

This iconic black and white photo of Dr Phillip Tabane was taken by Hugh Mdlalose at the Market Theatre in 2004. (35mm Fujicolor Superia Xtra 400 ASA pushed to 800, Nikon FE 2, 105 mm, F 2.5, 250 shutter speed).

The Hidden Years Music Archive documents alternative music and music-making in South Africa from 1967 to the early 2000s. The archive, collected by David Marks, is estimated to house more than ten tons of material including live and studio sound recordings, photographs, newspaper clippings, posters, magazines and various documents. The archive’s history, the music it preserves, and the stories of those involved in the events documented here speaks of encounters between different genres, cultures and races, of music that tended to circulate outside the conformist spaces of a musical mainstream. For more information please visit https://aoinstitute.ac.za/

| 1. | ↑ | Mignolo, W. 2011. Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World. Download here: |