STEPHANUS MULLER

The Island

‘It is isolation, then, that makes the island what it is’

Peter Sloterdijk, Foams[1]Peter Sloterdijk, Spheres, Vol. 3, Foams: Plural Spherology, tr. Wieland Hoban (Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2016), p. 290; Germ edn. Sphären III: Schäume (Frankfurt: Editions Suhrkamp, 2004).

In this picture, which was taken at Waenhuiskrans, South Africa, in 1958 when Graham was seventeen, he and composer Arnold van Wyk crouch next to a fishing boat. The forty-two year old Van Wyk had just completed his major piano work, Night Music, and Newcater was visiting him in Stellenbosch to receive instruction in composition. In an undated letter, presumably from December 1958, Van Wyk writes to conductor, Anton Hartman, about Newcater’s visit:

Newcater, that DURBANITE protégé of mine, is here for a few weeks … He is a shy, introverted boy; surprisingly mature and ripe for his seventeen years (he looks about twelve) in some respects, and in others still pure child. He has brought with him a wealth of works and in all of those I have seen thus far, there are signs that he is perhaps, indeed, a composer. But he writes too fast, too much and is without discipline; his approach is also not always that of a craftsman.[2] Stephanie Vos and Stephanus Muller, Sulke vriende is skaars: Die briewe van Arnold van Wyk en Anton Hartman, 1949-1981 (Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis, 2020), p. 200. The photographs were sent to Hartman in a subsequent letter, dated 29 January 1959. Translation from the Afrikaans by the author.

In this photograph, it is the difference between how the faces of the two men, or the boy and man, relate to the air around them, that interests me. Van Wyk doesn’t only seem to be in the environment, but involuntarily interacting with it, his hair blowing in the wind, his mouth slightly open, his eyes exposed to the sun, the air moving about him. Graham’s shortly cropped hair looks tightly styled, his mouth is shut, long eyelashes covering the apertures of vision.

He was already becoming an island then, I think.

I have been struck, in my engagements with Graham over many years, by his isolation. When I met him, he was already an old man. He was living in a house in Kenilworth in Johannesburg, with his late wife, Anne. I visited him in this house not frequently, but a number of times, sometimes on my own, sometimes with friends and colleagues: the pianist Mareli Stolp, the composer Theo Herbst, the filmmaker and artist Aryan Kaganof. He was not the kind of person one met in a coffee shop or a restaurant. One telephoned (he does not have a computer, or e-mail), and one arranged a visit. Only very recently, when I wanted to speak to Graham while doing research abroad, did his stepson help him to download Whatsapp, which we have since been able to use.

Isolation in old age is not inevitable. That is: If and when the good fortune of continued health and financial independence enable freedoms like travel, making new friends or renewing old acquaintances, or doing things unshackled from work and routine. Isolation, in such circumstances, emerges not only as a choice, but one with shades of possibility: Isolated in this way, but not in that; isolated from them, but not from them; isolated now, but not then. In Graham’s case, by the time we met, his isolation already seemed to have become formidable, and not purely imposed by material and physical circumstance. For one thing, he had always lived in a metropolis, that foaming tumult that is Johannesburg, which Ivan Vladislavić has lovingly chronicled in so many of his elegiac sentences. In three such sentences, from Double Negative, the photographer Auerbach, looking out over Bez Valley (not that far from Graham’s neck of the woods), reflects on houses and suburbs that ‘had survived the cycles of slum clearance and gentrification and renewed decline’:

If I try to imagine the lives going on in all these houses, the domestic dramas, the family sagas, it seems impossibly complicated. How could you ever do justice to something so rich in detail? You couldn’t do it in a novel, let alone a photograph.[3] Ivan Vladislavić, Double negative (Cape Town: Umuzi, 2011), p.

Perhaps Vladislavić would object to the description of Johannesburg as a ‘foaming tumult’. He did, after all, call it the ‘Venice of the South’ in Portrait with keys; which by the way, has been translated into German by Thomas Brückner as Johannesburg: Insel aus Zufall, a title that can be translated either as ‘Island by coincidence’, or ‘Island by accident’.[4] Ivan Vladislavić, Portrait with keys: Joburg & what-what (Cape Town: Umuzi, 2006), p. ; Germ edn., tr. Thomas Brückner, Johannesburg: Insel aus Zufall (Munich: A1 Verlag, 2008).

Graham’s isolation seemed to derive neither from coincidence, nor accident. The man I got to know did not garden, did not tend to his house, did not make journeys, did not venture out into the world in even an everyday, humdrum kind of way. Or so it seemed to me from spending limited time with him in his house during visits, sitting in his lounge with him, discussing music, or standing next to his desk in his bedroom where he writes his music, or next to his piano in the same bedroom, where he would play new pieces for me. I remember him as moving with great difficulty, more so as time went on, requiring help to get from the lounge to his bedroom. After the passing of Anne in 2021, he became confined to his bed.

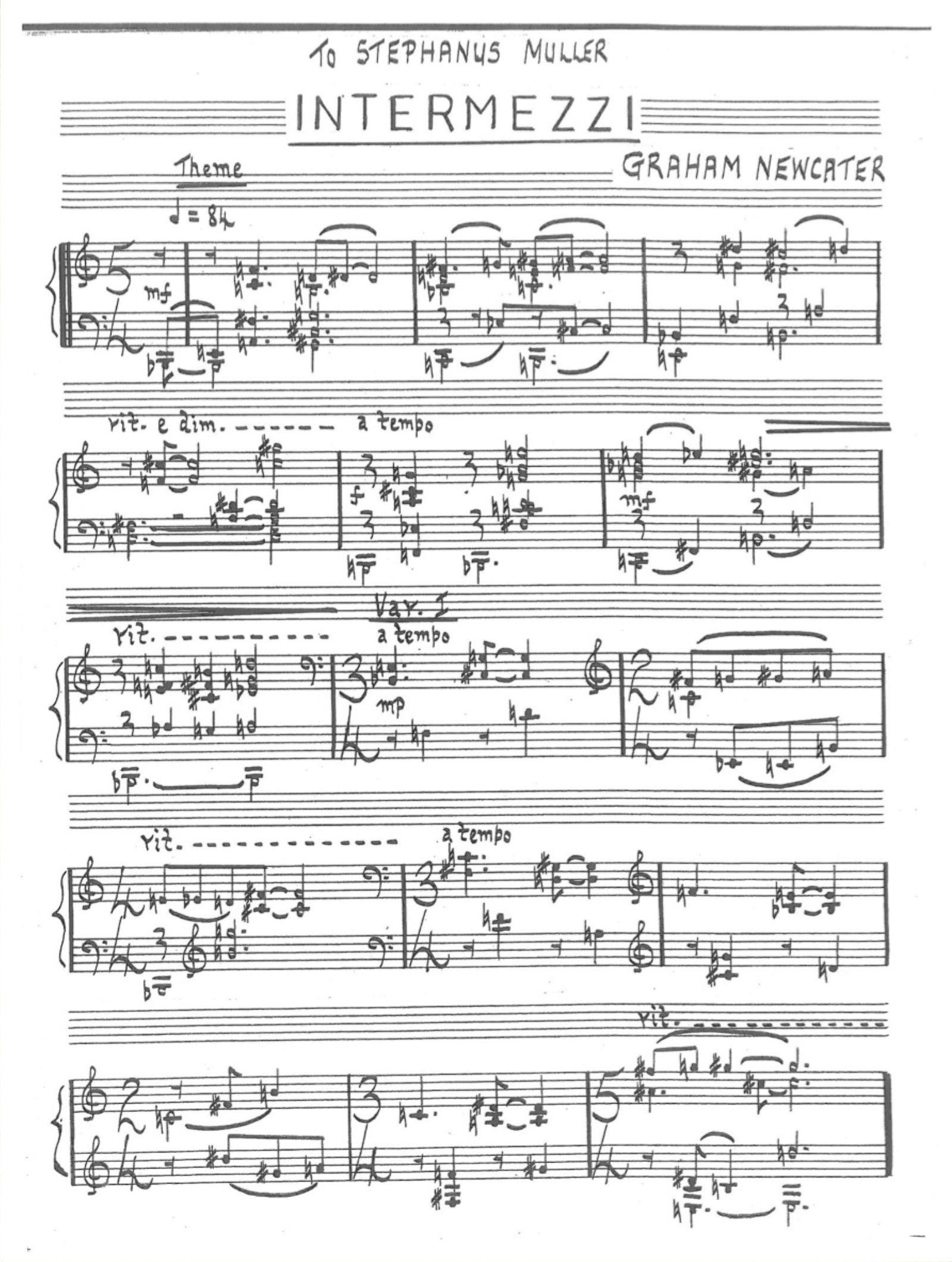

How does one do justice to something so impossibly complicated, so rich in detail, as a life lived as an island in a house in the city of Johannesburg? Let us not consider a photograph, for now, or a novel, or Aryan Kaganof’s short film Of Fictalopes and Jictology, or those occasional academic encounters that tend always to be less than. Let us consider a piece of music, Graham’s latest work, the Intermezzi for piano. I have an electronic copy of the work in my possession, as Graham dedicated it to me, and had had a copy of the score scanned and sent to me by the South African Music Rights Organization.

The Intermezzi is the latest in a slew of piano works written in the past decade.[5] Mareli Stolp notes ten new works between 2011 and 2018, including the Sapphire Sonata (2016), two Toccatas (2012 and 2016), a Sonatina (2014), From the garden of forever (2014), Canto (2015), Chromatic serpent (2016), Sonic poems (2016), Nocturnal variations (2017) and Autumnal improvisations (2018); See ‘Graham Newcater: Composing untimely’, in South African Music Studies (SAMUS), Vol. 40 (2021), pp. 29-55, esp. p. 31. It is an interconnected series of pieces, structured as follows:

Intermezzo 1

Theme: bars 1-7

Variation 1: bars 8-15

Variation 2: bars 16-23

Variation 3: bars 24-31

Variation 4: bars 32-39

Variation 5: bars 40-49

Intermezzo 2: bars 50-83

Intermezzo 3: bars 83-125

Intermezzo 4: bars 126-144

Intermezzo 5: bars 145-183

Intermezzo 6: bars 183-226

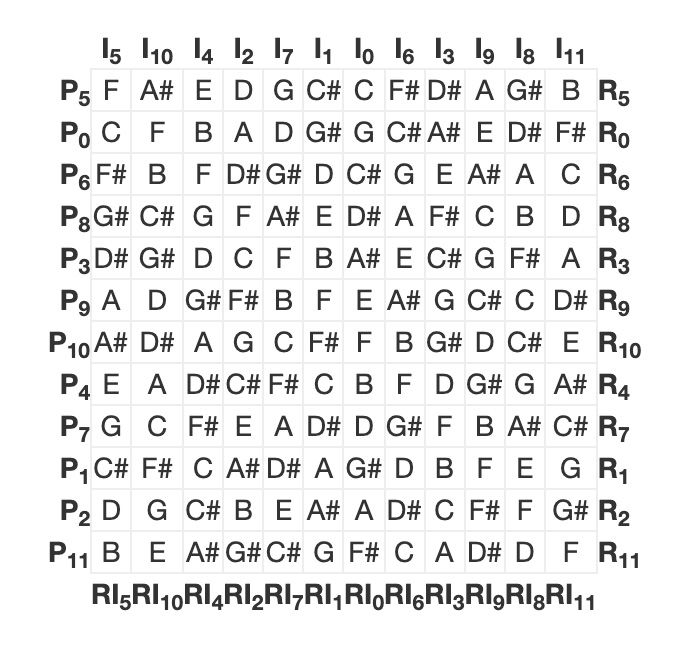

Intermezzi 1, 2 and 3 each has a different prime row, while Intermezzi 4, 5 and 6 are based on the same prime row. These rows can be seen in Graham’s sketches, which he had sent to me upon my request, and which are reproduced here.

Here is the prime form for Graham’s first Intermezzo, with intervallic relationships between the pitches described: Perfect 4th – Diminished 5th – Major 2nd – Perfect 4th – Diminished 5th | Diminished 5th – Minor 3rd – Augmented 4th – Minor 2nd – Minor 3rd.

Graham’s holograph score shows his deployment of this row in the opening gesture of the work (and with varying degrees of comprehensiveness, also in the rest of the work), as follows:

What is puzzling in this small fragment of the first two bars, is what exactly the series means for Graham in the light of his disregard for the intervallic relationships implied by the row. Let us remind ourselves that Schönberg’s system of composition did not exclude any pitches in the twelve-tone tempered scale – all twelve pitches were to be used – but on the manner in which these were deployed: Strictly in series; or in any of the 48 permutations allowed by inversion, retrograde or retrograde inversion (again, strictly in series), with dominance by any single tone avoided (though not forbidden) through proscription of tone repetition or multiple use before the series had exhausted itself, and tonal direction often erased, obscured or avoided in the series construction through the avoidance of cadentially-inclined semi-tones or functional harmonic succession. It is therefore the relationality of pitch, rather than pitch itself, that was made the subject of an apparatus of composition. This very aspect of relationality – defined as the intervallic relation of one pitch to the next – seems of complete disinterest to Graham in the way the Intermezzi are composed. Their maker looks upon rows and inversions as collections of pitches to be arranged at will, with the movement from pitch-set to pitch-set losing its meaning through exactly the non-serial deployment of the twelve pitches in every row. Put in other words: If every pitch is accorded its position in the horizontal or vertical deployment according to ‘musical’ considerations, or the tensegrity of the structure, this is no longer serial music as such, but a kind of free atonality, framed by rows, that floats in the idea of the series as an arc of deliverance, an isolator from whatever counts as outside, and that enables passage for all sorts of passengers:

In the example above, pitches 12, 1 and 11 of the prime form combine, with the passing note on pitch 3 (E) to give us a tonal gesture from a different time and place, carried to safety in something the composer calls a row. And even though the chord itself may be an island of sorts, brought into life by its row as life support system, as it were, it does not appear by accident or coincidence. Here it is again, five bars later, emerging from clouds of clusters:

Of course, the original Tristan myth had something to do with a voyage to and from an island, although Wagner substantially rewrote it for his Tristan und Isolde, where this chord is made to carry so much longing and desire. And so, as its appearance in the fifth variation of the first Intermezzo shows (in bar 43), it is not so much that Graham has retained twelve-tone music as system, but rather that he has maintained it as an atmosphere in which to express the longing of the man who has become, in Deleuze’s formulation, the deserted island himself.[6]Deleuze cited in Sloterdijk, Foams, pp. 288-289.

That the ensoulment of longing should happen through rolling back the row’s allegiance to the series shows, if anything, how firmly his rows hold his music – and his world – together. Within their conditions of possibility, this is an example of the rich detail that Vladislivić’s Auerbach despaired to find in the photograph, or the novel: The circumstance of an octogenarian South African composer who, in 2020, writes what he describes as twelve-tone music pioneered a hundred years earlier by a composer who would become a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, only to make a chord comprised of an artistically arranged row that happens to conjure up the historical infidelity of an anti-Semitic megalomaniac in an enduring Teutonic love fest called Tristan und Isolde. Now there’s richness for you, and complicatedness, right in the heart of Johannesburg.

Outside the Wagner Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, as one approaches the Green Hill from the town, there is a bust of the great German opera composer by the Nazi sculptor Arno Breker. Surrounding it, is a now permanent installation entitled “Silenced voices”: The Bayreuther Festspiele and the Jews from 1876 to 1945. It tells the story not only of how the Bayreuther Festspiele was enthusiastically embraced by Adolph Hitler (and vice versa), but also how many Jewish musicians lost their livelihoods, and lives, because of persecution. One reads there, in English translation:

The self-exonerating claim that Richard Wagner was misused by the Nazis is true only to a limited extent. Even though there was no direct contact between the two, Wagner was nonetheless a key source of inspiration for Hitler. But it was Wagner’s heirs who first established direct political links. It was through their defamation and marginalisation of ‘Jewish’ artists, their misuse of the Bayreuth Festival and their participation in anti-Semitic and anti-democratic organisations after 1914 that they helped prepare the ground for the state-organised expulsion of ‘Jewish’ and ‘politically unacceptable’ artists after 1933. This is the central proposition of the present exhibition.

Viewing Breker’s Wagner bust, surrounded by the metal plates inscribed with the histories of silenced voices, flanked by pictures and documentation of the shameful collaboration with a murderous regime, is a disconcerting experience. Wagner is detached, isolated, the Latin ‘insulatus’, made into an island in the company of others who, like himself, have now made the great crossing.

I find it difficult to imagine how one views the installation, and then goes inside the theatre to listen to the music, perhaps after having had a drink at the restaurant/bar right next to the installation, the Ring Lounge. I suppose things move on, and people do too. Which brings me, quite naturally, to Hans Baldung’s (c. 1484-1545) Die Sintflut (The Deluge), painted in 1516, and exhibited in the Staatsgalerie Bamberg, not far from Bayreuth. It is a chaotic scene, all those sinners, smitten by a vengeful God in a grand reset of history. But also animals, and babes, old men in their dotage, priests. Centre in the painting, one sees an unlikely looking, top-heavy, gabled wooden structure, resembling more a travelling chest than a seafaring vessel. The most striking feature of the painting, for me, the element chosen by Baldung to convey the chaos of a world in the throes of apocalypse, is the foam, and the way in which the arc, or that part of it that sticks out, is set apart by its stark geometry from the bubbling, heaving, pulling formlessness of the foaming waters. For sure, a less optimistic birth from foam than Botticelli’s Venus, painted a mere thirty years earlier, but a form rising from foam all the same.

The arc is what Peter Sloterdijk has called ‘an explicatory form for island formation’,[7] Sloterdijk, Foams, p. 294. a maritime prosthetic island that sheds light, for those on the inside, on the conditions of life. It is the uncompromising rectilinearity of Baldung’s arc, just the shape of it, that made me think of Graham’s rows.

About what kinds of atmospheric conditions these rows have allowed the composer to navigate in the more than six decades during which he has been writing music. In the first twenty years, as a child and young man in the Union of South Africa; then, for the next thirty, as a student and mature composer in the Republic of South Africa when it required adoption to, or acceptance of, the psychosemantic imagination called apartheid, and then, for the next thirty, as an increasingly isolated individual carrying the parasite of that imagination in which he had been raised and to which he had adapted. When I think of Graham, of his life as a composer during apartheid and beyond, I can see how his music was a form of auditory self-determination that also had the function of group delineation. But I can also see how Graham’s rows were nothing like an acoustic tent for South Africans, then or now.

Even more than Graham’s enduring use of this method of composition, I find his eagerness to show how he has put the composition together, interesting. There is a willingness to explicate, to bring the background into the foreground, that is unusual. It is as if the composer is demanding that all the energy expended in engaging with the work, be concentrated inwards, towards the work, away from the house in Kensington, and Kensington the suburb, and the Venice of the South – Johannesburg, and the province of Gauteng, and the Republic of South Africa, and the continent on which it is the southernmost political entity. Look inside, the rows seem to ask, not to the foaming frame of the arc, but to the way in which the rows live in the composition. To return to the beginning, for that is one way to end things, I would hazard to say that it was not like that for Van Wyk, who crouches in this picture next to Graham, his hair blowing in the wind, his mouth slightly open, his eyes exposed to the sun. The man who in 1958 had just completed his major piano work, Night Music, and who was never eager to say much about how his compositions worked, or were made. He wanted his music to be in the world in another way; not as explicated manifestations, but as dreams. And it may well be that Graham already understood something else, that December morning when he was photographed next to his teacher, and the boat, when he shut his mouth, and squinted, warily, into the distance, surprisingly mature and ripe for his age.

And of course, there is no telling what that something else might have been.

| 1. | ↑ | Peter Sloterdijk, Spheres, Vol. 3, Foams: Plural Spherology, tr. Wieland Hoban (Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2016), p. 290; Germ edn. Sphären III: Schäume (Frankfurt: Editions Suhrkamp, 2004). |

| 2. | ↑ | Stephanie Vos and Stephanus Muller, Sulke vriende is skaars: Die briewe van Arnold van Wyk en Anton Hartman, 1949-1981 (Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis, 2020), p. 200. The photographs were sent to Hartman in a subsequent letter, dated 29 January 1959. Translation from the Afrikaans by the author. |

| 3. | ↑ | Ivan Vladislavić, Double negative (Cape Town: Umuzi, 2011), p. |

| 4. | ↑ | Ivan Vladislavić, Portrait with keys: Joburg & what-what (Cape Town: Umuzi, 2006), p. ; Germ edn., tr. Thomas Brückner, Johannesburg: Insel aus Zufall (Munich: A1 Verlag, 2008). |

| 5. | ↑ | Mareli Stolp notes ten new works between 2011 and 2018, including the Sapphire Sonata (2016), two Toccatas (2012 and 2016), a Sonatina (2014), From the garden of forever (2014), Canto (2015), Chromatic serpent (2016), Sonic poems (2016), Nocturnal variations (2017) and Autumnal improvisations (2018); See ‘Graham Newcater: Composing untimely’, in South African Music Studies (SAMUS), Vol. 40 (2021), pp. 29-55, esp. p. 31. |

| 6. | ↑ | Deleuze cited in Sloterdijk, Foams, pp. 288-289. |

| 7. | ↑ | Sloterdijk, Foams, p. 294. |