SIMBARASHE NYATSANZA

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: Making Africa visible in an upside-down World

In 2016, one of Africa’s most revered and celebrated intellectuals and fiction writers Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o published Secure the Base: Making Africa Visible in the Globe, a non-fiction book made up of seven essays. The crux of the book is about making Africa visible, and the seven essays presented are an attempt to critically address aspects of the invisibility of Africa, of Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. It is important to note that the essays are in the main not written strictly as essays but more as a fusion between the essay form, reflections and speeches. It is also important to note that these essays proliferate ideas that the author has wrestled within various forms for more than half a century.

In Secure the Base, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o charges both the West and Africa for the invisibility of Africa. The charge against the West is rested on its erasure and denial of Africa in global politics whereas his critique of Africa rests on self-betrayal by Africa, especially its elite. In a peculiarly existential manner, wa Thiong’o posits visibility with appearance, appearance to presence, presence to essence and essence to an ethical relationality with the self and other in authentic global solidarity.

As a body of work, the book traverses a myriad of topics that are threaded together by the central call of returning to the base. The base is the people of Africa to be secured from the existential challenges that affront their humanity. He attends to these challenges that contribute to the insecurity and invisibility of Africa successively with each essay, some essays echoing and reifying earlier ones within the same book, and others doing the same for his ideas articulated elsewhere.

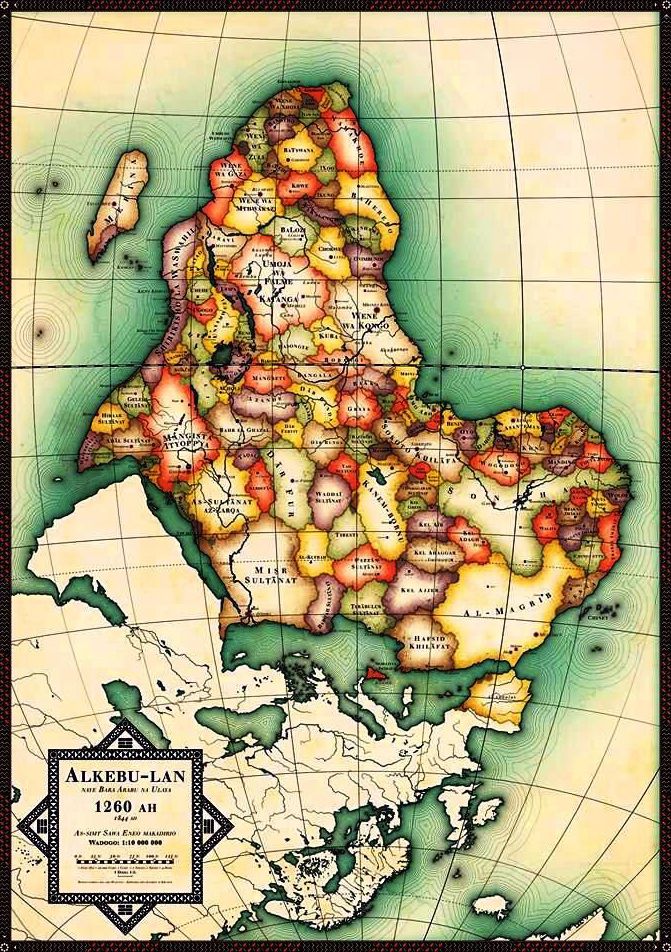

In the first essay, Contempt and Self-Contempt, wa Thiong’o challenges Westerners and Africans alike but from different perspectives, although ultimately for the same charge of diminishing Africans. The central question in this essay is around the choice of terminology and its implications. Specifically, he takes issue with the marker of “tribe” when describing African groups versus the marker of “nation” when it is Europeans. He drives this point home by pointing out that 40 million Yoruba are regarded as a tribe yet 5 million Danes are regarded as a nation. For Ngũgĩ, this reduction of African societies into demarcated hostile groupings is also a reduction of personality and identity in that the “tribe is like a genetic stamp on every African, explaining his utterance and action, particularly vis-à-vis other African communities” (page 7). The dangers of this for Ngũgĩ is that the global (European or otherwise) gaze and designation of Africa is that of a breeding ground for ethnic and cultural animosity instead of “normal” conflict. He warns that this conception and formulation excuses the damage done by colonialism and its border-making cartography that intentionally suppresses peaceful coexistence.

Ngũgĩ also claims that colonialism created – and neo-colonialism perpetuates – the existence of two tribes in Africa: the Haves and the Have-nots as opposed to African communities being reduced to ethnicities. That the proliferation of capitalist fundamentalism has created a world where one’s heritage and culture is deemed inferior to what they can produce in thrall to corporations which wa Thiong’o describes as the third tribe. In order to secure Africa and eradicate its invisibility through its tribalization, it becomes imperative to reject the power and controlling nature of the word “tribe” in order to recognise these three afore-mentioned tribes, created by capitalist expansion, as the real enemy.

The second essay Privatize or Be Damned warns against the market fundamentalism which characterises Western modernity. He asserts that “Technology offers the possibility of plenty. Profit motivates human ingenuity to create scarcity. The means to salvage life is demeaned by the means to salvage it” (page 19). In here he attacks the basic tenets of capitalist logic and he chides the glorification of the market over the need to change fundamental structural problems and identifies this as the latest manifestation of capitalist fundamentalism. Ngũgĩ extends his warning even to civil society, especially in the aid industry, via non-governmental organizations (NGOs) which inadvertently protect global finance which is the lifeline to this sector and through it neo-colonialism has infiltrated even those bodies that are supposed to be the safeguard of societal integrity.

From land dispossession, slavery, the slave trade and postmodernity to debt slavery, the essay encourages a questioning of the West’s hand in the continued impoverishment of Africans with its collaboration with the national middle class that continues to choose splendour despite the squalor that fellow Africans live in. To counter the adverse effects of this set up, Ngũgĩ proposes a continental common market in Africa, drawing inspiration from the East African Community (EAC) that must also function as a group to put the people first. In doing this, they will not only ensure the creation of Afrocentric economies but will also use this economic and political unity to advance a borderless Africa in line with the founding ideals of continental organization.

New Frontiers for Knowledge is the third essay and reiterates Ngũgĩ’s sustained position on language, not only vis-a-vis decolonization but also in the (re)production of selves that are true to our essence as Africans. He continues his challenge to African intellectuals in embracing and celebrating diversity that will strengthen and restore memory and history in the languages of and imagination of the people. He stands for an Africa where citizenship is not excluded based on class, and cultural divides are extended by an over-reliance on colonial languages. For Ngũgĩ, it is not sufficient to value representative democracy, but it must also translate itself to different iterations that will be ideal to African people in ways that African “democracy” can be understood and embraced by the people, i.e. the base. Echoing the sentiments of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, Ngũgĩ asserts that we “must not pay tribute to Europe by creating states; institutions and societies which draw their inspiration from it…(page 60).”

He urges African intellectuals to not assume the inferior role of informing capitalist modernity on the native ways of life as taught in Anthropology as a child of colonialism. Rather, the task is to “create a common intellectual basis for the unity of Africa…” (page 75) in an effort to not become outsiders in our own country by revering the impact of colonialism and by not re-examining our colonial heritage as a people. He argues that an African intellectual that seeks to restore African languages and African systems of knowledge must not use colonial languages for anything other than to enable the elevation of African languages in order to “plant African memory anew” (page 76) and these ideas he proliferated spectacularly in his classic Decolonizing the Mind (1986).

In the fourth essay, titled Responsibility to Protect, he gravely notes the helplessness of most people in the face of national and international conflicts and the importance of a body like the United Nations (UN) to intervene and resolve conflict on their behalf. He also recognizes power plays in the United Nations where phrases like “the international community” are used as euphemisms to mean the West (more specifically North America and Europe). The dangers of this if left unchallenged are already manifest, that invasions and government overthrows can happen under the guise of the responsibility to protect and no real accountability can happen with these nuclear-possessing countries with veto powers at the UN Security Council while Africa has none due to disarmament by Libya and South Africa. This inequality between nations he also notes within nations and that the same formula is at work, the Haves plunder the Have-nots with the former consuming resources overwhelmingly produced by the latter in unequal power relations thus creating splendour on squalor. The solution for Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o comes from the recognition, the making visible of the common people, the base, not the middle classes of nations, as only the base can be a true measure of societal progress. There is a need to close the gap between and within nations for real and sustainable structural equality facilitated by democratic organs of the United Nations (unlike the Security Council) in order to end splendour rested on squalor. In this essay he extends the Marxian critique he levelled in the second essay Private or Be Damned and this is the leitmotif that runs throughout this book.

The fifth essay continues the overall concern against the invisibility of Africa and Africans even in the diaspora as advocates for the recognition of slavery’s centrality in the making of the modern world. Titled The Legacy of Slavery, he shows how the modern world still relates to Africa in the same way as it did during slavery through different mechanisms such as debt slavery through which the West maintains its hegemony. The West still sets the agenda of relationality through trade regimes that favour it and credit management that keeps Africa in check and further dwarfs the potential of African people. He essentially ties the prospect of visibility to the proper mourning of slavery which he locates in the recognition of the slave trade and slavery so as to properly note the origin of modern day capitalism. To further this project of recognition (visibility) wa Thiong’o argues that efforts should be dedicated towards creating an internationally recognized period of mourning. Accordingly, this process will help with healing the wounds created by the enslavement of African people as well as facilitate the “wholiness” of the world.

In the penultimate essay Nuclear-Armed Clubsmen, Ngũgĩ revisits his preoccupation with the role of the intellectual. He makes another Marxian move that locates the intellectual as labourer with language and words as means of production whose products are not of immediate material utility as the intellectual cannot eat or wear their products. The products of intellectual work are at best ambiguous as genius can be used for evil and good hence Ngũgĩ’s appeal to intellectuals to recognize their work, and what their responsibility therein is. To drive this point home, he highlights the case of J. Robert Oppenheimer of the Manhattan Project and how his genius was used to create Death in the form of an atomic bomb much to his regret.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o makes a sharp turn towards encouraging intellectuals to be in service of the people (the base) and not side with abusive wielders of power in imperial and or colonial projects. He reminds us of the vulnerability of the world to the dangers of nuclear power and that the world has no policy other than to hope that the nuclear powers will not abuse their position but history does not provide any evidence for this likelihood. Ngũgĩ believes in the role of the intellectual as the harbinger of peace in line with the Marxian-Gramscian framework he operates in. For Ngũgĩ, it is important to recognize that the countries with nuclear power are also the countries with colonial pasts and armament is directly proportionate to economic wealth.

The final essay Writing For Peace revisits some of the ideas he advanced earlier in the book and in his career overall with a biographical reflection on why he personally cannot afford to treat matters of peace and war with indifference. He notes that the global community is plagued by two rifts: a fascination with ethnic/cultural lines which breeds animosity and the inequality that exists between the national elite and the working majority. He asserts that these rifts are somehow upheld in service of modernity and progress due to capitalist fundamentalism. Charging writers and intellectuals alike, the book maintains that there needs to be an encouragement of hatred towards imperialist exploitation and “crimes against humanity” through the raising of human consciousness by “warriors of peace”. He argues that world peace can only be achieved by a shared respect for the humanity of all, where the development of one nation does not mean the degeneration of another but rather it must assure mutual development, between and within nations.

In the end there is an underlying thread that ties all of these essays together, namely the concern of security and visibility. The time lag between the essays can serve both as a strength and a weakness. A strength in that some of the things that were relevant decades ago are still shamefully relevant even today, which means the world is not making tremendous progress.

A weakness in that some of these concerns have been advanced by others and their relevance is not due to ignorance but to self-interest of the powerful nations and their unrelenting need to exploit Africans for their benefit and no altruism within or between nations is possible and therefore Ngũgĩ ’s realistic analysis of the situation of the world is undone by his ahistoric hope against hope that the West will ever be anything other than what it has always been.