RIAAN OPPELT

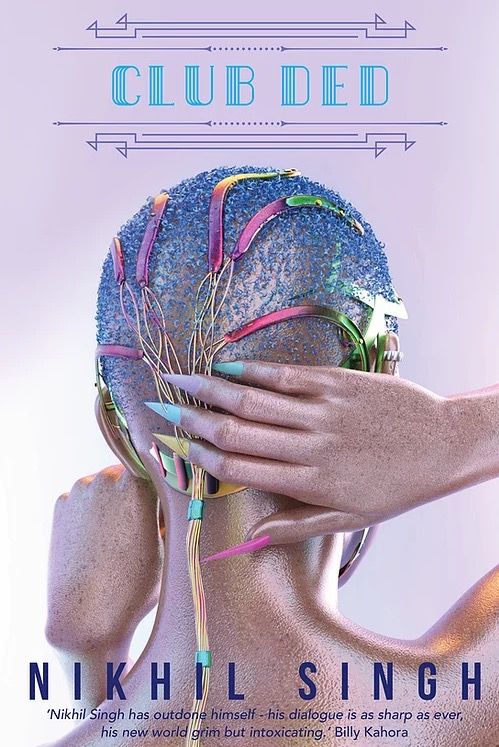

Club Ded: psychedelic noir in Cape Town

This review of the novel Club Ded by Nikhil Singh will be divided into two parts. The first, shorter part is the formal review of the book. The second, longer part is an informal review essay. The first part is to do the book justice and to provide that which a review is tasked to do, namely shed light and discuss the qualities and merits of the text. Nobody need read further than that. The second part is a personal take that tries to straddle intrigue and a deeper dive into the effects the novel have left on a reviewer thinking through his own view of Club Ded’s author. Trivia, guessing games and desperate attempts at rising above fanboyness are all in the terrain of the second part.

Page numbers cited correspond to the Kobo e-book version of Club Ded I purchased and made use of for the purposes of this review.

Club Ded is an important novel, one that has plenty to say about the times we live in. The times we live in are also simultaneously tethered to the past and to the future and so, Club Ded is a work that will influence newer voices and also references some voices of the past, voices from different mediums, owing to the author’s consummate absorption into so many different artistic fields. Or, if I’m supposed to work off the premise that the author is dead, as per my training in Literary and Cultural Studies, then the text itself shows these qualities. Some will call it a cyberpunk/post-cyberpunk masterwork; some will call it another great work of Afrofuturism and some will call it a proudly South African book. All of these recognitions could be both right and wrong, and I doubt the author, Nikhil Singh, would easily agree with any of them because he has expressed, time and again, that he’s not into labels. He can make great use of them, though. Viewed as psychedelic noir, the book already has dedicated fans and the same goes for those in the Afrofuturist/Afrocyberpunk camp and, as ever, the proudly South African camp—and the latter designation would probably irk the author.

Truthfully, I would not know how to classify this book without pretending that I have great knowledge of any particular label bestowed upon it. I think it is a Nikhil Singh masterwork and I’ll say more about that later. It is, for now, a great work of literature and for the rest of this review, I will try to motivate why I say that.

The title of the novel may bring back associations, for some, of Club Med, but you’d really have to remember the 90s for the last time the holiday/hospitality group that is/was Club Med was spoken about as a thing, despite its 1950s—2010s lifespan; it’s still around but under a different name and, you know, really corporate in that 21st century way. “Following the herd down to Greece on holiday” was Blur’s cheeky summary, in 1994’s Girls and Boys, of ordinary, lower-to-middle-middle-class English yobs holidaying on the Mediterranean and unleashing their hedonistic tendencies via Club Med resorts. Essentially, it was traveling pretty far for that drunken lay on a rocky beach vibe that seemed to be something to aspire to in the name of adventure. People thought they were edgy, or something; it was cute. That was the world before influencers and the Kardashians, basically.

Pleasure, epiphany and extra-sensory experience are prevalent in Singh’s Club Ded and the Cape Town setting is its own spin on Club Med ridiculousness, as mostly the non-South African characters in the text are standard-issue epicureans coming to a tourist haven pretty much rigged for the self-indulgent behaviors of the foreign rich, or basically anyone with currency favored by the exchange rate that makes even the local Camps Bay millionaires only so many envious chimps living delusions of their global status. Later on, I’ll have a few things to say about the significance of Club Ded as the ultimate Cape Town novel but, for now, the setting tells us a little bit about what to expect: the forced and one-sided pleasure palace Cape Town aspires to be is a logical place for some wonderfully dreadful characters to unravel their stories in.

Club Ded, in the novel, is both the name of a film and the name of a space dedicated to that film, but it goes deeper than that, and more disturbing. Once or twice, a character in the novel knowingly teases the tease of devices in fiction that appear to be prominent from the outset, then seemingly disappear from the narrative only to make cameo appearances in the final act—but a cameo appearance that still leaves you with questions, as it should. With such a trick, readers may be left wondering whether all that they’ve experienced over nearly 400 pages was really the metonymy. This happens with Club Ded, the space (of course, you never see the film but it is exciting at how the end product of it is put together, all the way from Hollywood control rooms to a hidden basement in Langa), and also the characters Desmond and Despierre. Spoiler alert: although the novel starts off with them two, they’re a bit Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, serving one of the novel’s key focus areas, the #MeToo era. By the end, you’ve seen Club Ded, the space, but you’re not quite sure what you saw because, when you take in what goes down there, and how it ends, it may be too troubling to process immediately. The novel pulls that off remarkably well, the slow burn of (in)digestion not unlike the one that plagues the character Jaybird.

The making of the film, Club Ded, brings most of the characters to Cape Town, although their connections and backstories clearly have origins further back and in other geographies. Cape Town is a meeting point not only of two oceans but of characters from quite a few parts of the world, as if the novel is winking at Robert Ludlum’s spy thrillers where everyone usually meets and kills one another in Paris. The film set is a disaster, with production running late and over budget, and Brick is asked to patch up with Croeser and help out. The making of the film is a cover for a far more insidious project that has ramifications for the future existence of the elite, which, naturally, has larger ramifications for the not-elite, as always. In some unfathomable way, the novel predicts, after a fashion, the whole billionaires-going-to-space moment we’re currently trapped in.

Characters directly involved in the making of Club Ded, the film, include

Brick Bryson, a washed-up, alcoholic action star who somehow still has ‘it’.

Del Croeser, a notorious director who fell out with Bryson when a film they made together back in the 90s won him an Oscar that ought to have been Bryson’s. Croeser is a notorious user and abuser, a sociopathic Svengali always ready to exploit a young woman working in movies. You’d think he was South African because of his name and some of the racist things he says, but he is a Transatlantic type, as far as I could tell.

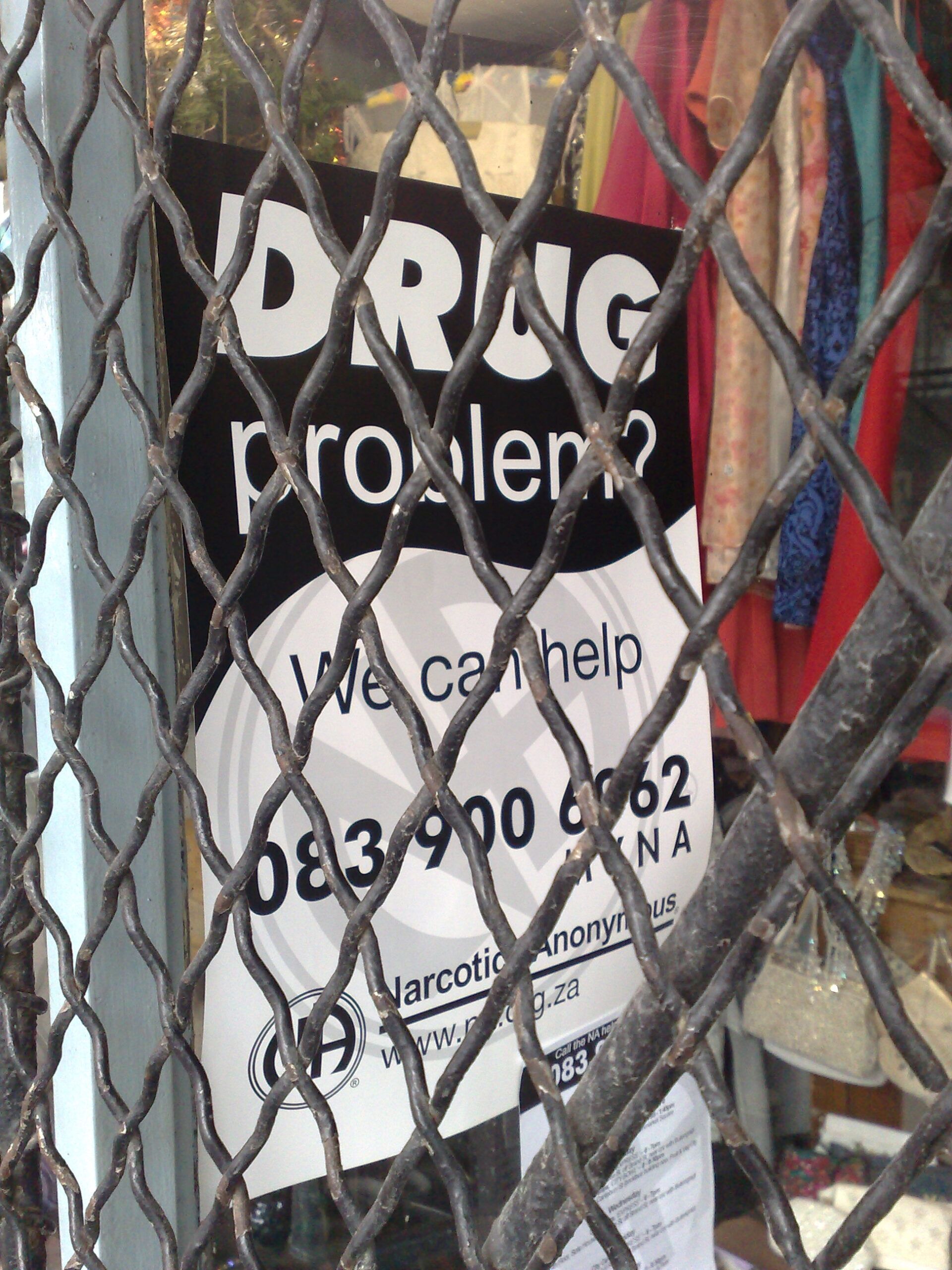

Jennifer, Anita and V, three young women often described as The Blackbirds who work for the mysterious but all-prominent ‘Oracle Inc.’, run exclusively by women, and headed by a woman known only as The Oracle. Jennifer, Anita and V also run favours for Croeser on the film set and they do a lot of drugs; like, a lot. V is an exciting character bringing with her knowledge of border-jumping between African and European countries and she has an uncanny instinct for figuring out how to puppeteer the filthy rich on film sets. Jennifer swims a lot, more than I’ve seen any character swim in a novel. Swimming is big here, partly because of a natural drug extracted from fish glands that most of the characters are on. The fish glands are known as suicide pills and actually mediate the effects of other, hard drugs. Jennifer comes to have large parts of the narrative devoted to her interiority but she does, eventually, have a direct link to the filmmaking process of Club Ded. She is plagued by nightmares of the future and her own mortality. Her friendship with Anita is not immediately obvious but it grows in terrifying proportions as the novel progresses.

Fortunato, a Nigerian filmmaker who was once married to V and whose crafty, guerilla-style filmmaking comes to feature prominently in the text. He is the assumed leader of a revolutionary underground deconstructing much of the Cape Town/Hollywood artifice in the novel. He is probably my favorite character, an absurdly talented creative able to maneuver in various fields, including being a petrol head. He is also behind the fish-extracted psychedelic that is taking over the streets of Cape Town, although he is by no means your common-or-garden drug dealer.

Ziq, a master pickpocket who was once a pianist playing in places in New York. He and his friend, Jaybird, a psychotic American, make for many of the walking scenes through the city and, through his emerging relationship with one of The Blackbirds, he is pulled closer to the world of Club Ded, an outsider with some sense of a better world behind all the bullshit. Jaybird, however, is a pyromaniac. Now you know who to blame for the Table Mountain fires every year.

There a number of other characters. They seem to be bit-players but somehow, everyone has a role to play in the perplexing Club Ded project. It becomes about seeing a spectacle movie’s production through to its end but that production is eerily tied to too much going on around Cape Town, and Hollywood for that matter. And Cape Town and Hollywood both play their parts in feeding into everything that is wrong with the planet.

The novel offers marathon commentary on how neoliberal globalization and commercial trappings have suicided South Africa, with Cape Town as a palpable entry wound.

Some of the discussions characters have about the history of South Africa would raise the eyebrows of even the most hardcore decolonists for their sheer scope and rebuke. For a novel with its eyes on the future, the present reality and the history of things is never far away from any acidic paragraph, and there are many of those. In some ways, I interpret the novel as looking at Cape Town and asking, ‘How the fuck could you do this to yourself, you idiot?’ Achille Mbembe’s recent predictions that a new world order could only be read exclusively through Africa, with Africa as a new theory and not a site for Eurocentric theory, almost seems to be at work in the novel at all times.

This South Africa, Brick notes, is a depressing place not of tourist-imagined jungle but of bleak, sandy and parched landscapes both in the Western Cape and in Gauteng. Cape Town reminds Brick of LA—in a bad way (89). A lion hunting outfit in Gauteng specifically rigged for wealthy tourists to hunt domesticated lions is named ‘Aluta’—the struggle continues. Fucked up, but true and you know it.

These following quotes, uttered by the heinous Croeser to Brick while they ride in a limo at night around the Cape peninsula, struck me exactly because a scumbag like Croeser spoke them, sounding for all my money like any mass-property owning fuckwad you’re ever going to encounter in the Cape, in Kwazulu-Natal, Gauteng, anywhere. He is Noah Cross of Chinatown in this moment, and as that film is about the corruption of life-giving water in ways that are tragically normal by now in Africa, his comments from the limo vantage point resonate hauntingly:

‘I wouldn’t put too much stock in the rainbow nation, Mandelafication of it all,’ Croeser tells him. ‘That’s just retail. Economically, the place is a sinking mess.’

‘Looks alright to me,’ he says.‘It’s the ultimate, corrupt, vacuous, nouveau-riche society,’ Croeser booms preachily. ‘These assholes want what the first world has. But they’ve never experienced it first-hand. They can’t experience it!—to do that you need to travel. And you can’t do that very easily on a South African passport.’‘It’s difficult to travel on an SA passport,’ V agrees. ‘Only the privileged get to do it.’ (67)

The film production is, to my mind, almost indisputably a study in #MeToo politics and power struggles, amplified by the small but significant appearances of reporters keen to expose Croeser as the exploiter he is. The sexual exploitation is woven into the novel and with the psychedelic drugs in the mix, there is a constant questioning of reality and pondering about where the power lies in any given room. A number of characters of all genders are frequently without clothes just to remind us that sex, drugs and everything else always sells. Some of the episodes are meant to be disturbing even when they’re played for dark laughs and it seems the novel never wants readers to forget that. An Afrikaans trouvrou-type, in particular, seems to hammer this home as she gets out of her head with each appearance in the novel. She is preposterous but the narrative around her is frightening, too.

Club Ded is a game-changer. It is not for everyone, it might be too much breakthrough and I think its impact might be a slow burn but one way or another, the book cannot be ignored. I have criticisms and they’re mostly to do with what I think amounts to shoddy editing and proofreading; this is a shame, as the book deserves better. Sometimes, it is the way a sentence is broken up and that is stylistic, part of the how the text tells its story. But other times, there are errors and you notice them and they glitch the experience somewhat. This does not take away from the brilliance of the novel. It is up there with some of the best narratives I have ever read and I strongly recommend it.

II This is the ‘Detachable’ part of the review

It was daunting to be asked to review this book, for numerous reasons. Maintaining objectivity, not overhyping the text or making it sound like ‘Insiders Only’ trumpeting (I hate that, myself) and then also just because of my respect for the author. And my respect for the author means that I do remember, even when I don’t want to, his public utterances about so many topics related to art and then, inevitably, these utterances impact my writing and then you find it here, in the chatty, detachable part of a book review. I was asked to review this book by Nikhil Singh and immediately my brain went,

The Nikhil Singh who started writing novels at the age of 9, when he was already well-versed in jazz music thanks to his exposure to dives where authentic jazz got played?

The Nikhil Singh who is like an urban legend even now in certain parts of Cape Town, Pietermaritzburg and Durban, spoken about by those who once say they knew him back in the early noughties? The Nikhil Singh of The Wild Eyes who, purportedly, lost a bet and had to take human form? The Nikhil Singh who’d diss William Gibson and say his ‘tepid’ Neuromancer was aping cyberpunk trends in Japanese fiction prevalent years earlier? Is unimpressed by Bergman, and Antonioni? Sees Denzel Washington and his complex posturing as a source model for Brick Bryson? (I had fun re-imagining Courtney Vance, myself.) Goes for the snail stories of Patricia Highsmith rather than her novels? Knows the value of arcane 70s and 80s made-for-TV movies and series, especially dingy cop shows? ‘Gets’ 1980s macho action with its bold, Rambo-esque title fonts and makes sure his savvy local filmmaker in Club Ded, Fortunato, knows it too?

That Nikhil Singh? To me, it was a petrifying prospect.

Firstly, I am no expert on African speculative fiction, psychedelic noir, cyberpunk or post cyberpunk, for that matter. I know the basics that some of you would know, and Nikhil would laugh at us even if we were so-called authorities. In fact, the tendency to define African speculative fiction by race and politics irritates him no end, something he has slammed as ‘media-programmed superficial bias.’ Regardless of which genre you throw at me (does that sound like #AllGenresMatter?), my job is to work with literature and, fuck me, that’s what we’re dealing with here, epic literature. I’ve read a lot, and you’ve read a lot, no matter which forms your texts take, be they written or lived, but I’ve not read something like this. Perhaps not all great writers need to be great readers but Nikhil, you’ll soon find out, has possibly read everything. This is an encyclopedia of a being who did not need a university to turn him on to the outrageous talents he has; this is like Good Will Hunting but, you know, without Matt Damon-as-Ben-Affleck’s proxy—Nikhil would fuck Will Hunting up on any turf.

I do count myself as a fan of Nikhil Singh’s and remaining objective was going to be a challenge. I also think Nikhil Singh is miles ahead of many writers around the world, at least all the writing I am aware of. Such bold statements get you into trouble because then you are being just a fan, and I think that in over 25 years, that’s something the internet has ruined somewhat: pure criticism. Too many fans pose as critics and too many critics are terrified of fans, or try to win fans by spending time thinking of creative ways to slag something or someone unpopular off (easy targets, since the mob has already decided), rather than doing the work of criticism. Everybody wants part of some pie and sincerity and authenticity shrink, which is exactly the kind of practice Club Ded works against, that sycophancy of entertainment value and put-upon moral stances that pose as art and criticism. In the fashion of both classic film noir and the early 1920s hardboiled American pulp fiction that played a part in its inception, as well as gritty French existentialist novels and films that immediately preceded American film noir, Club Ded ruthlessly exposes so much of the hypocrisy going around in so many facets of post-truth life. The novel deflates our digital age ‘morality’ and shows that the worms that were underneath the veils a hundred years ago in works like The Maltese Falcon (the novel) are still there, but bigger. Truly, it could not have chosen a better place than Cape Town for such exposing. The ‘Mother City’ with the usual associations of nurture and care? The Mother City ‘where South Africa began’ and where commercial sloganeering gets regenerated on a daily basis online, on radio stations, in Promenade art (Ray Bans, anyone?) and museums on First Thursdays? Fuck off.

Club Ded as a great Cape Town takedown

I do not know if it is wrong for a reviewer to see how much of their own life’s sightseeing is in the novel they’re discussing. A fan could do that; surely a reviewer should not? The Cape Town map the novel sets out is very much my map, or I wish that it is my map. I live right next to the recurring site most of the novel’s thoughts and actions take place in, and have lived there for almost 20 years, long enough to see the changes the novel snidely remarks on time and again. Long enough to know I’m hardly any better than the plebs or ‘chimps’ walking through the Company Gardens in the novel.

The Cape Town on show here is not unlike my own unfulfilled dream of recasting the city as something out of Nathaniel West. I’d tried to write the famous trek through Hollywood sets from Day of the Locust as an excursion through inner city Cape Town but never had the courage to finish it. Club Ded does it effortlessly, and lest we forget, Nikhil references West early on already when it becomes clear that, on the surface, Jennifer, V and Anita do Miss Lonelyhearts-type work. Just to keep us honest, the novel namechecks that novella 200 pages later.

A detailed map of Cape Town runs throughout the novel, with more attention given to the side-streets and hidden arteries than even the recent spate of (pretty good) detective fiction set in the city. Driving scenes take you on trips on the N2, the N1, Camps Bay and Chapman’s Peak, and a few detours to the ridiculous bridge at the Foreshore. You get to Langa, Cape Point, Observatory, Salt River and Gardens, quite a lot. The petrol head and dicing culture of Cape Town (and Durban) gets a look-in, even though there isn’t any racing.

Jaybird, a screwed-up American, is the novel’s resident pyromaniac, a note that hits too close for a city in which its main attraction, a mountain, burns almost on cue a few times each year (my band and I even wrote a song about it some years back during the drought, imagining a character not dissimilar to Jaybird). Close to the end of the novel, he lights his biggest fire, something straight out of K. Sello Duiker’s Thirteen Cents. He rolls on the ground, laughing in a deranged manner even as he gets the shit kicked out of him. In this moment, by this point in the novel, you’re utterly sick of the Cape Town of Club Ded, as you should be. Like the real Cape Town, it’s not a great place; it keeps burning, like the burning Hollywood Tod tries to realize in Day of the Locust.

Cape Town reminding Brick of LA—in a bad way—is not a good look. In the novel, it is a warning.

Music

There is little that is conventional about Club Ded. One cannot find familiar tricks or tropes to get one through it. I was left for dead 20 pages in already, and I’ve lived through Finnegan’s Wake! Music was needed to help me catch up to the novel. I came to know Nikhil’s artistry through his music, even before Salem Brownstone and his graphic art legacy, and it is with music that I think back on Club Ded. Permit me to take a winding route with this one. When some youtuber tried to break down the guitar playing style of Robert Fripp, formerly of prog-rockers King Crimson, the youtuber had trouble because, good as he was, Fripp’s work fell outside the blues rock wankathons he’d mastered. Transparent about his limitations at covering Fripp, the youtuber simply said, “You can’t approach this as you would the legendary players; he’s not that kind of guitarist.”

When I heard Nikhil’s work with The Wild Eyes, his solo album Pressed Up, Black, his Hi-Spider and Witchhouse stuff, I knew that this was no ordinary, 4/4 bar-obeying musician. Reading his prose, all I could think was, “He’s not that kind of writer.” That being any writer following certain inherited, respected conventions, from setups, buildups and three-part structures of establishment, conflict and climax. Fuck that, it’s the Godard-of-Weekend approach here of beginnings, middles and ends not necessarily in that order. Even when many of the characters have their narratives neatly tied down by the last pages, it still feels as if the text is giving you chocolate for public consumption. If Nikhil sneers at most of the world and its commercialized, hive-mind values from his fb page, he does so even more compellingly in his prose.

To repeat, I needed music to help me through Club Ded and, fittingly, it was Nikhil’s own music that naturally came to me. Most of the novel is set during summer in Cape Town, but I found myself listening to Winter Wonderland from Pressed Up, Black during those scenes (perhaps because I’m currently in Germany, at the mouth of the Black Forest, watching winter come in). The quiet scenes between Jennifer and Ziq had me hearing Suicide Sunday, perhaps because of the suicide pills in the novel, or perhaps because their quiet moments were as vulnerable as Deckard and Rachel’s in the frightening world of Blade Runner (original cut, the one with the annoying but legendary voiceover); these moments seem to have comedown Sunday silence in-between the loud, violent weekend sociability-as-sociopathy of everything else. And what about Jennifer, the character the text seems most invested in? How could I not remember and go back to track 5 of Pressed Up, Black, the track named Jennifer? The cacophony of the entire novel’s stylistic attack I found years ago already in Nagasaki Nikita, still the best thing I think he’s recorded.

Dialogue

Taty Went West came with Nikhil’s music and his visual art but I’m glad the text barrage of Club Ded is one, unbroken monolith because it puts the onus on the reader to re-imagine their own imagination (it’s just an illusion). It gets dense and you have to wade through it as if you’re one of the characters in syrupy blue water—and there’s a lot of water and swimming in this novel. Besides, the text plays with itself and with you in cheap but titillating games of prose position and concentration: there are moments where description disappears entirely and you’re left with very obvious, scripted dialogue that would be at home in a movie because, hey, everyone here is linked to the production of a film called Club Ded, and many of these characters know when they’re speaking scripted dialogue straight out of pulp fiction, with a touch of Harold Pinter’s mastery of subdued but menacing theatrical dialogue. One of the characters even has to fix up the film’s working script with ‘witty, postmodern’ dialogue. Often, it seems as if the characters speak merely for sound effect and have much fun doing that. Some gems include:

‘No-one can save the world to witch house.’

‘Corporations are the new colonists. Or, rather, the old ones—wearing different party costumes. They’ll ruin entire populations for a fat slice.’

‘Don’t tell me you’re another of those sentimental African-Americans.- Coming here to recolonize Africa under the pretense of “getting back to your roots”.’

‘No, I’m an American. I hate it here.’

‘Good.’

‘In the end, I was the only one there for him. He repaid me by falling in love—so irritating.’

‘So, the two of you had a good chat?’

‘… At the point of a knife.’

‘He is very dramatic.’

‘I noticed.’

‘I heard she’s a racist.’

‘I won’t lie. She’s… abrasive.’

‘She feels that she is somehow superior.’

‘I suppose.’

‘And you?’

‘Oh, I think we’re all equally worthless.’

Even some of the descriptive passages are meant to be film-like, such as the meeting of the old, worn-out action star, Brick, with Sasha, the new, young hot-shot who took over from him. They meet atop a sandy dune at the Western Cape’s Atlantis (!), Brick having trudged up there and clearly struggling while Sasha, in his introduction in the novel, stands majestically in his pomp at the summit in his superhero costume, his cape flapping in the wind like the newest MCU money-flag. The text tells us that ‘Brick had assumed that Sasha had not noticed his approach. So, he is surprised when the star addresses him without even turning his head.’ Classic, commercial film scene, that, befitting almost any era of big, Hollywood production. His back turned to Brick, Sasha speaks his first lines in the novel, posing them as a question:

‘Did you know that thus part of the country is the only landmass that didn’t move with the continental drift?’

Because of course a young, woke movie star would say that. He adds:

‘It’s stayed in exactly the same place since all the continents were joined. It’s the navel chakra of the world!’ (119)

Because, of course, of course a mega rich film star would say that. I couldn’t help but see so many of Nikhil’s fb missives at idiot celebrities (and their followers) preaching climate change while being hedonistic, LA-based energy wasters. (Come to think of it, I could see some Cape Town-based ‘celebrities’ also easily fitting that mold.) They all deserve Ricky Gervais at the Golden Globes, roasting them at their own self-congratulatory parties.

While the clumsiness of human relations and dependencies in general is a great characteristic of the novel and, to my guessing, possibly inspired by John Huston’s Night of the Iguana, a favorite of Nikhil’s, it is the depiction of couples that provides Club Ded with noxious susceptibility. Nikhil’s great feeling for portraying the sustaining of deteriorating, malignant two-person relationships in the rotting body of reality is straight out of a number of sources that are both referenced in and omitted from the text, seemingly everything from Two Weeks in Another Town to The Swimmer—and I even wonder if I detected the poisoned vulnerability of Emily Dickinson there, because, if he wanted to, Nikhil could lecture on her, too. I don’t mean that it’s always the same two people but one character and their singular relationships with other individuals. Each time you think Club Ded is about any two specific people it becomes, like The Swimmer, a dive into any one character’s relation with any one other. I don’t think it’s a coincidence, either, that for a novel not particularly set out at sea (apart from one scene at the end), there’s this much water and swimming (in enclosed locations), as if the 1968 film by the Perry spouses is swimming throughout the text like a cell.

With this in mind, it is my only sadness that the two-person relationship depicted with the most irresistible screenplay-like flourishes is also the relationship least explored yet most powerfully intimated. That is the relationship between struggling alcoholic and unfaithful Brick and his wife, the highly intuitive and generous Lisa-Marie. They have two scenes together, one at an airport and another over the telephone. Their relationship hit by a Brick scandal that rattles even the battle-hardened and passive Lisa-Marie, she references her pain as a film scene during their phone conversation:

‘God, it’s just like a film, isn’t it? The speech the wife makes, starring me as the wife. I’m just a cameo now. Only two appearances. One at the beginning to set a tone of morality and another at the end to deliver judgement. I used to get all the witty one-liners. Now I get this jilted wife shit. I haven’t trained for this!’ (325)

Back in the 1990s, such a moment would have been merely annoying, one of many oh-so-postmodern self-references probably written by Kevin Williamson and Paul Auster. Given where we are in the supposedly hyper, selfie-aware and narcissistic 2020s, even that annoying quality of such a moment now seems desirable, and I wished there was more of Lisa-Marie and Brick in the novel. She shows up pretty much like Beatrice Straight does in Network (1976), another character disappointed at having to be a jilted wife, and also just in the narrative for a few moments (but walks off with honours, as Straight did by winning an Oscar for 5 minutes of screen time).

Conclusion

Thanks, if you’ve made it this far to the end of my ramblings about Club Ded—but that was your choice. Read Club Ded. There’s nothing like it going around at the moment.