KOPANO RATELE

What Use Would White Students Have For African Psychology?

1

“It was September 2021 when I finally had an opportunity to teach African psychology to an undergraduate class,” I will say to the student of the history of psychology when she finally comes around to asking about the significant milestone in the development of this body of work. I recall that the local government elections were to be held at the beginning of November – and there was neither intellectual nor political inspiration to be found in that direction.

The class was online, via MS Teams. The country was still under government lockdown related to the COVID-19 pandemic. All the same, the online class turned out to be as satisfying as can be. I did come to realise that being in the same physical space with students possesses an irreplaceable layer of multi-sensory experiencing that is hard to achieve online. Yet, I saw even better how digital technologies, beyond enabling education to continue during crisis periods such as a health pandemic, individual-paced learning, economies of scale, cost effectiveness in the long run, and other advantages, have made possible a significant goal for African psychology. With a powerful means of information and image creation and dissemination placed in the hands of the multitudes, for instance in the form of a smart cell-phone and technological applications, at the click of a button the making, discussions and circulation of African psychological knowledge has become exponentially enhanced. There is no longer a need to bemoan the lack of access to the global knowledge-making machine (whatever its pitfalls): we just must produce the content and put it online – whether it is images, numbers, sounds, or words – and from that some interesting ideas and debates, and even new futures, might become possible.

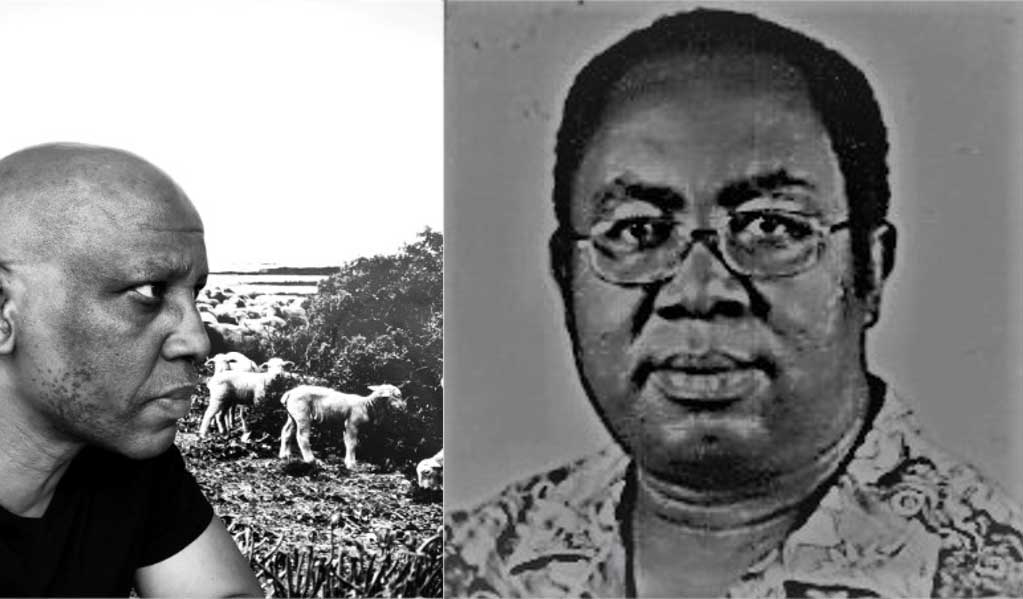

The first lecture I delivered was on my work and the debate that I had been having at the time with Augustine Nwoye, the Nigerian-born thinker who was based in South Africa at the time, on the nature, objects and horizon of this object we call African psychology. All the lectures touched on the debate, in fact. I have never told him this, but as he represented an identifiably specific take, I owe much to Nwoye in prompting me to keep writing about my thinking on African psychology. Anyhow, a central issue in the debate we had was on whether this object with which we are concerned is a discipline or a stance, and, for me, the implications that either would have.

Nwoye is, in my terms, what I call a disciplinarist. I am a situationist. He believes that African psychology is a discipline.

I approach African psychology as a way of orienting ourselves in the world.

The debate began with a question by Nwoye. The question, what is African psychology the psychology of, was also the title of a 2015 article published in the journal Theory & Psychology.[1]Nwoye, Augustine. ‘What is African psychology the psychology of?’ Theory & Psychology 25, no. 1 (2015): 96-116. My response to that question, published in the same journal two years later, was also in the form of question: ‘Why is all of psychology in African countries not African psychology?’[2]Ratele, Kopano. ‘Four (African) psychologies.’ Theory & Psychology 27, no. 3 (2017): 313-327.

And four years later, in another article in the same journal in the company of Nick Malherbe, I had another question: what and for whom is a decolonising African psychology?

I gave four lectures in all on African psychology that first year. Giving those classes was, at the time, a big deal to me. The significance of the moment was not so much that I was teaching students on these debates about African psychology that had been going on, however interesting the debates were to some of us. The import was that this was the very first time I taught my work to a class of first-years. I had supervised several postgraduate students over the years who had conducted African-centred psychological research work, however I had always felt a pressing need to lecture undergraduates on African psychology.

A few months earlier, in July of that year, I had started as a professor of psychology at Stellenbosch university, after 14 years as a research professor at the University of South Africa where I was one of those professors given the privilege to not teach. In passing, it took me a long while to fully realise the absurdity of having non-teaching professor in universities in a country like ours, one that is demonstrably struggling to get an education fit for itself rather than pretend it is a rich Western country. The notion of non-teaching faculty may work in the mathematical and lab sciences, perhaps; however I became convinced that

in the humanities and social sciences, in a country where millions need education, having professors whose only job is to think all day and write a couple of papers nobody will read anyway is possibly not the best use of resources.

All professors in the latter fields in a middling country like ours should teach along with doing research and social engagement. The more experienced they are the more they are needed in front of undergraduate classes, because the practice of having younger and less experienced lecturers teaching undergraduate classes is simply preposterous. Here too, though, it is power that sets the rules. Regardless, one of my motivations for going to Stellenbosch University was precisely to teach undergraduate classes – specifically African psychology – after my long absence. But I digress.

The occasion of teaching African psychology to undergraduates at Stellenbosch University was, one must admit, marked by a densely meaningful and ecstatic paradox. I should elaborate. The paradox is one I had always unconsciously felt, in the form of a question: do white students need African psychology? I am thoroughly convinced that to teach any psychology student in an African university that does not abundantly situate psychology within the society in which that student experiences life and shapes her psyche is more than bad education. It disorients them for life. As such, a good basic education in psychology is psychology from the standpoint of a living society. Given the history of our society, students who identify as African are the ones most in need of an education that enables them to see themselves and their world more clearly. Seeing that my first classes on African psychology were given at Stellenbosch University, a university that was created to serve the interests of white, Afrikaans-speaking students whose ancestors largely rejected identifying with Africa was a fantastic irony. In such a case, is it necessary to convince them that in order to practice psychology at Stellenbosch it is necessary to think from Africa instead of America? Is one impelled to persuade them that the whiteness of psychology is a problem and they as students in an African university need an African psychology to enable them to see themselves more clearly?

In 2021, the first-year psychology class was still predominantly white, and my assessment of my discussions with some – not all – of my colleagues and students was that the psychology department, and other departments at the university, had not quite resolved their identity confusion with respect to being African. In short, we were a department in a university in Africa but not always clear whether or how we were African. Come to think of it, teaching African psychology – actually, teaching anything about Africa – at Stellenbosch feels like the beginning of really a good absurdist television drama. One day, let us hope, someone will create something like the television series The Chair[3]The Chair was a 2021 Netflix series created by Amanda Peet, and Annie Julia Wyman and starring Sandra Oh, about the first woman of color, Professor Ji-Yoon Kim, to become chair of an English department at Pembroke University. maybe called The Department, about teaching Africa at Stellenbosch University.

To go back to the class, I recall having an inexpressible feeling of lightness after the first in the series of lectures. It was like I was floating. I had to take a long walk in the afternoon so that I could feel the ground under my feet and bring myself back to reality. I would write a post on Facebook – which was popular at the time – about what I was experiencing. I asked my online friends whether they ever had that feeling that what they are doing during a particular moment is something that they should have been doing forever, and that they could go on doing this thing forever more? It was one of those moments for me.

The night before the first lecture I stayed up close to midnight still finalising the lecture. I was a bit anxious about how I should draw the students in, make them see that

all understanding begins with self-understanding.

I went through several ideas about how to bring to life the concepts I wanted to convey. At one point I toyed with the possibility of talking about Euroamerican psychology and African psychology as a kind of blue pill-red pill choice. The metaphor of blue pill-red pill is portrayed in the 1999 science fiction action film The Matrix. Written and directed by Andy and Larry Wachowski, starring Keanu Reeves and Laurence Fishburne, the film depicts a dystopian future in which humanity is unknowingly trapped inside a simulated reality.

The pill metaphor refers to having to choose between going on and living in the world as it appears, the regular life, or choosing to learn a potentially new truth, that one is in fact trapped. The metaphor raises to conscious awareness precisely the idea that we might be colonised and we would not even know it. When the mind itself is colonised, there is no quick escape. Reality is not what it appears to be. But you would not know that.

Stellenbosch University had redesigned their first-year psychology courses, actually. For the first time, I think, the students were learning about global and local experiments to decolonise psychology. And psychology desperately needed decolonisation, a point powerfully brought to us by the RhodesMustFall and FeesMustFall student revolts of 2015 and 2016. To be fair, there was no discipline in South Africa that did not need decolonisation. But even though the psychology department at Stellenbosch University had made efforts to cast light on colonial elements of psychology, the preponderance of the classes on psychology in the department were Euroamerican-centric, and the Euroamericanness of the psychology was too often glossed over. So, a reference to the blue pill could have worked. However, I was concerned that most of them would not know what I was talking about as they would not have watched The Matrix. I did not go with that. But I hope somebody reading this might watch the film and make the links with African psychology as opening new vistas of truth.

At another point I considered telling them about what I had been learning from watching Korean television dramas on Netflix. I thought one could ask, how does one watch Korean drama while African? Speaking of television, it seemed to me that television (and I have mentioned films, but also radio, newspapers, and magazines, as well as social media) is something that is scarcely broached in African psychology classes and there was a huge lacuna that needed plugging. We are still around, it is not too late, and there may be a chance still to do so. In any event, I had been watching a lot of Korean and Chinese television series at the time. I was, at the same time, watching Indian and Nigerian films. I became much more interested in the films of Sembène Ousmane and old African cinema. I was, that is, even more actively and consciously shifting my gaze from American film and television. To paraphrase the lines of the hip hop group Dead Prez, I ain’t gotta watch it just because they advertise it a heavily.

Regarding Korean and Chinese television work, I was fascinated with their dramas depicting Korean and Chinese histories as well as those about contemporary love in Korea. And I toyed with contrasting Korean television dramas with American dramas for the lecture. I felt it would be a good way to draw the students in and have them think about African psychology as trying to bring to life psychological dramas that are different from the dramas depicted in Western psychology. I reckoned the students could go home and watch these dramas for themselves afterwards, before the next lecture, and hopefully better appreciate some of the ideas I would have discussed in the class. But I did not go with that idea.

I do not know whether it was the students who had more fun, or whether I was having the most fun. But they were engaged, asking a lot of questions. That was most stimulating. I recall one student asking, why would African American psychologists who started African psychology look to Africa for answers to the psychological problems they were encountering? This was in relation to the point I had made that African psychology as a discipline was invented by African American psychology.

Another student asked, when Nwoye said African psychology is a discipline, and you say it is a set of orientations, what is the real difference between a discipline and an orientation?

And the best student comment was this:

what do we do with all this Western psychology we have been taught?

I would answer some questions, but for the most part I would throw the other questions back at them. And the ensuing discussion quickened my heartbeat. At the end of the class I felt that if this is what universities teach, and, I playfully said to myself, what teaching can induce professors to feel, I would want to be a student again and maybe I will be that kind of professor.

2

Some points about the content of the 2021 lectures are warranted. In two of the lectures, I showed short videos I had made with my students of psychologists talking about their work. An aim of making the videos was to demonstrate how different psychologists have thought (or not thought) about what they do and, more importantly, about identifying as African psychologists or not. It still surprises me that to call oneself an African psychologist remains controversial in South Africa. I wanted to present differing views to students and hoped they will see the different interpretation of what is African psychology. I think some may have glimpsed the different interpretations that can be advanced about what it might mean to be an African psychologist.

At the beginning of the third lecture, I showed a video made by the journalist and filmmaker Leila Dougan. Titled Why revolt, the video is on my work on African psychology and I am a talking head in the video. The point I made to the class regarding that video is that psychology is in society and psychology students, teachers, therapists, are part of families, schools, universities, communities, countries. That seems like an obvious point, however you have to read psychology textbooks to realise it has tended to be divorced from the situation in which we live. As conveyed in textbooks, psychology is often divorced from actual existing social reality. Like an all-seeing God who is everywhere, it exists outside of society.

The motivation that had led me to make all these and other videos was simple. I wanted to create content that I could not find when I searched on the internet.

Sometime in the early 2000s I had been struck by the fact that when I typed the word “masculinities”, an area of interest of mine, I did not get many works on African masculinities and men from African countries. How could this be? Similarly, when I searched for “psychologist” Google gave me no African psychologist. Did they not exist? Even more intriguingly, when I entered “African psychologist”, I only found “African American psychologist”. This needed to be fixed.

It was then that I realised that we cannot merely complain about the neglect of African thinkers or their absence, in whatever discipline or profession we associate ourselves with, if we have not produced the content to fill that lack. Some of the content would draw attention to the work of those thinkers who have been neglected. Some would be new content which did not require having on video a Chabani Manganyi,[4]Noel Chabani Manganyi is the first black person to receive a PhD in South Africa. For example, see Manganyi, N. Chabani. Apartheid and the making of a black psychologist: A memoir. NYU Press, 2016. Hussein Bulhan,[5]Hussein Bulhan is a Somali psychologist. For example, see Hussein A. ‘Stages of colonialism in Africa: From occupation of land to occupation of being.’ Journal of Social and Political Psychology 3, no. 1 (2015): 239-256. or Bame Nsamenang[6]Bame Nsamenang was a Cameroonian psychologist. For example, see Nsamenang, A. Bame. ‘Factors influencing the development of psychology in Sub-Saharan Africa.’ International Journal of Psychology 30, no. 6 (1995): 729-739. speaking about child development, trauma, or men’s aggression. One could find clinical psychologists or critical ones who have thought about doing psychology from the perspective of being here, informed by their social situatedness, the life around them, to tell the world about their thinking.

I therefore set out to produce online content on African psychology, work that I have continued to do since then, to surface the fact that African psychology is a thing, prove that African psychologists exist, beside the fact that we are having all these debates. The problem that I sought to address was, to be clear, threefold. First, while in comparison to American psychology the numbers are relatively small, I simply wanted to show that there is work on psychology by academics and researchers in African countries. That was it. I did not have to like the work. I just had to reveal it. And second, I also wanted to privilege work that I regarded as out-front. The kind of work that showed seminal thinking. That is the work that needs to be highlighted more. And finally, what I was also missing, and that I felt was needed, was the kind of material that was more amenable to the age of Google, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. In other words, content that was short, less text-heavy, privileging voice and more visuals, and easy-to-digest. Such content would include short videos, posts, and tweets.

It had always been part of my plan to show Why revolt? to other audiences, not only in the lecture room or conference hall. The aim of showing the video was to talk about its making and what the intention had been and to receive feedback. More than that though, it was to stimulate the desire among others to produce online content on creative and critical African thought, to talk to audiences other than those in the professions and disciplines, to disseminate their work via different media. To put African psychology and psychologists online.

3

I said that media, be it broadcast or social, can enable or close down, offer possibilities but also be characterised by pitfalls, all of which signals that media and mediatisation deserves greater attention from African psychology students and teachers. The kind of attention that appears most productive is not studies on the psychology of media but rather locating psychology and our work squarely within the information age (keeping in mind the attendant misinformation and disinformation which are part of this age).

Ignoring the power of media and its representations in this age is out of the question. There is no alternative other than participation. The only question is how.

My sense is that most psychologists – and scholars and practitioners from other fields for that matter – do not quite realise the power of the media, and certainly do not participate in it. At a basic level many do not feel they have to engage the media to share and debate their work beyond the lecture room, conference hall, the journal pages and the book or chapter they have published. African professors of psychology are no different. In my assessment the preponderance of university professors in any discipline in most African countries I know of appear to share this sentiment. It seems to me there is a shared feeling that their work is to undertake research and teach, and maybe, write an odd op-ed or talk at a church, mosque, or school. Sometimes, some of us will appear on television or be a guest on a radio show. But, in my country, there are not many academics who do this kind of work.

So even though one’s work might get to be read by more people if disseminated outside academia, media of different types are dismissed as being equally legitimate vehicles to publish intellectual work. Of course, part of the blame is the incentive system that privileges peer-reviewed accredited journals, book chapters, conference proceedings and books.

As you may know, the incentive scheme has led to an increase in academic production but also an explosion of anemic and sometime very poor work. I even want to say, some of this so-called expert knowledge would be banned from Facebook because of how bad it is.

Also, publishing in predatory journals was at some point of great concern.

There are other reasons why the mass media is rejected as an appropriate vehicle to broadcast expert thought. Some of the reasons advanced against public engagement via traditional media – some of which I used to bring out when journalists or activists asked me to talk on radio, write for a newspaper, or even offer a view about a research topic I have expertise on – are that ‘I don’t do media’ or ‘we are not trained to write for newspapers’. When it comes to social media, some of us do not want to pay more than passing attention to it. I know some people who avoid it altogether. I can understand why. In my view, social media is a difficult environment to negotiate, much more difficult than radio, which I have tended to prefer, or television.

Social media has a lot of things of no use for one’s profession or discipline. Emotions can run high and wild on social media. The so-called discussion can quickly deteriorate into a verbal brawl. Presenting a façade – as the saying goes on Instagram, ‘living my best life’ – and performing for followers to get likes is common. Social media is also addictive. But just as some technology hardware and software became indispensable to professional tasks, social media, I think, has become unavoidable. But this is not a view that appears to be widely shared by psychologists.

To be sure, compared to, for example, using email to correspond with others, or ResearchGate where researchers share their work, social media is entirely a world on its own. People can pretend to be what they are not. Bots are common on social media. What you as a person say can be very easily distorted by others. You are communicating with people who have little knowledge about your work as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health expert.

Yet social media, like other media and books, surely allows one to correspond and share work or talk to others. By alerting us to the problems of social media I am therefore also suggesting one must be aware of and educate oneself about how best to interact with the world on/via social media. Running away is not the only option. It does not mean you have to be an expert in social media communication. It means being aware of the influence of the media in general and social media in particular, influence that can start riots, mobilise millions to bring down dictators, and to propel unsuitable people to the presidency of powerful countries.

4

We have not answered the question why one would want to subject oneself to the attention of the media, specifically, social media, when, with respect to psychology, one can happily work at home, the hospital, consulting room or office and publish or teach just as one has always done? There are several lessons I have learnt since the first moment I started to write op-eds and agreed to be a guest on television or radio. I want to concentrate on three of these lessons, baked into which are why academics, especially those doing African psychological theory and research, have to be on television, radio, and social media platforms like Twitter and YouTube.

First lesson: At some point I found out that I could relatively easily publish an academic article of 6000 words, but I found it hard to convey the same ideas in an inviting, easy-to-understand, 600-word long piece in a newspaper or discuss them on the radio. Compared to academic journals, newspapers and radio have many more readers and listeners, and arguably have more influence on people’s lives. But these mediums are not the preferred modes of dissemination for supposedly great ideas generated by academics. Most academics, among which I include myself, believe they are smart. Living in a country such as South Africa where the percentage of people with university degrees is relatively low and English, which is the dominant language of university education, is the third or fourth language for the majority,[7]In South Africa, only 7% of adults have a tertiary education, and only 6% of 25-34 year-olds were tertiary educated (OECD, South Africa: Overview of the education system: EAG 2021). South Africa’s overall Gross Enrollment Rates (GER) for tertiary education is lower than GERs of comparable middle-income countries such as China, Malaysia, Mexico Russia but higher than for African countries such as Cameroon, Ghana, Mozambique and Senegal. For instance, in 2018, South Africa’s GER was approximately 24%, those of China was 50% and Russia’s 85%, and those of Ghana and Mozambique were 16% and 7% respectively (Khuluvhe, Mamphokhu and Elvis Ganyaupfu, Access to Tertiary Education: Country Comparison using Gross Enrolments Ratio. (Department of Higher Education and Training, Pretoria, 2021).; see also, Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey. Statistical Release P0318. (Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2020.)

if some of the highly regarded work was to be published in a newspaper or disseminated over radio, audiences would rightly think, what unnecessarily complicated thing is this and why do we need it? One possible explanation for this disjuncture between academics and the majority of people in the country could be that academic smart is not the same smart that newspaper readers and radio listeners value. It is true that some academic writing is often intended to further entrench elitism by using deliberately difficult language. Publishing in elite academic journals that privilege difficult jargon and the rewards that reinforce such publishing effectively excludes creating knowledge for the majority of people and its contestation by them.

Over time, I have written many op-eds. I have come to know how to write a good one, I think. What I have learned over this time is that the length of piece of work or where the ideas are published has little to do with good ideas or their communication. To say that I realised that length is not an indication of the quality of ideas may be laughable to some readers. But alongside the questionable issue of the publication vehicle as an index of useful and impactful ideas, many academics conflate length with quality. This conflation is part of the knowledge production machine, of course, and begins in postgraduate university studies where theses have to be of a certain length to be acceptable.

Economy is however only one element in communicating to audiences beyond one’s profession and discipline. Among the critical ones is the ability to think from the perspective of the audience. Why would a person read my article when there are thousands of other articles to read: that is an important question to ask? Just because the topic is an important one to me does not mean it is important to the readers I wish to reach. If it is an op-ed, then, the point of the op-ed must be as clear. A hook is another important consideration. Respecting people’s attention, and hooking them, connecting to topicality, is necessary.

Second lesson: In taking non-academic publics seriously as academic ones, another lesson I have understood came from asking myself the simple question, what can I contribute to the discussion happening around me? It is not uncommon that another analyst or politician will say something with which one strongly disagrees or which is simply wrong. When that happens, one can choose to ignore what has been said. And many people will not know that what they read is wrong or that there are others like you whose research found different results or whose interpretation of the same data is different. Whether you write or talk about your differing research results or interpretation or you do not, if it is in the public interest, if it is topical, or if it bleeds, the media will cover it. And social media will take what is in the air and share it. There will be many comments. And the comments that get the most attention will be at the top. At times, journalists get it wrong. It is really one’s choice as a scholar whether to be part of what is happening in the world around you or not. But if one does, the question is how to deal with what is happening. The choice I make is to be clear about what I wish to communicate. I cut my message to fit the form without losing the key message. If it is a newspaper, I have educated myself on it. If it is radio, I ask, how many minutes. If is 5 minutes, my message should be short and to the point. If it is 30 minutes, I know that I will be asked, ‘so what can people do about it’ – whatever it is – and I will have to think of the practical implications of the work.

Third lesson: Between five and ten years prior to that first first-year class on African psychology, I finally came to appreciate more fully something vital regarding why we come to know what we know and what that knowledge has to do with what we think about ourselves and the world. The vital thing is this: power is the object of all knowledge. To say power is the object of knowledge implies that, among other things, the former authorises or constrains the latter, changes its directions or closes some avenues for it, makes it widely available or represses it. Some individuals and small groups need knowledge because it offers them power. Knowledge and the means of knowledge production are acquired or created (such as creating a radio station, academic journal, newspaper, or producing pamphlets) to enable some measure of control over people’s own lives and fortunes. Other individuals, governments, and corporations acquire knowledge or means of knowledge production (such as establishing or acquiring media company) so as to have power over what other people, individuals, small and large groups, whole societies or large parts of the world, think and how they act.

In realising the fact that power is the point of knowledge, which also means those regarded as experts ultimately want their ideas to have influence, including informing the decisions of those who have economic, military or political power, you might soon come to also understand that there are always efforts to control knowledge, to colonise it, to have people think in ways that an expert wants them to think. Think here of the example of the now common figure of the economist on television news channels commenting about currency fluctuations or the petrol price. The colonisation of knowledge is in fact the route when aiming to colonise the mind. Whatever other objectives the individual commentator has, he also wants to influence how we think. The efforts to control may be directed at any of knowledge’s authors, assumptions, substance, flows, reception or effects. These efforts are not always readily obvious. One ought to look closely and critically to see that knowledge is always intended to achieve specific objectives, and that power in its various manifestations is the ultimate aim. It makes sense therefore that colonial power was supported by colonial knowledge, but also that resistance against it would inevitably rise.

It should be clear that opposed to actions to control knowledge are efforts to challenge such actions. Therefore, whilst some authors and institutions dedicated to knowledge production and dissemination supported colonial power, there was also resistance against it. As such, to contest knowledge is to confront power. In appreciating that knowledge can be colonised, we grasp that a body of facts, analyses, methods, apparatuses, models and explanations and dissemination channels that constitute psychological knowledge can be roped into what people become, how they live, and, most importantly, how they are governed.

We grasp that when the colonial power that is seen in psychological knowledge does not keep emancipatory knowledge away from people to have control over their own lives, including keeping them uneducated, poorly educated, or miseducated, it infects knowledge.

Coloniality perverts knowledge, silences and erases that which does not serve its end.

Coloniality is the source of thinking that the ‘best’ knowledge is that which is created and conveyed in the coloniser’s cultures and languages. Colonial knowledge draws people’s attention from what would help them, or heal them, or enable them to thrive, towards knowledge that closes their minds. This is how I came to understand that my hesitation about African psychology, even inner resistance against this thing called African psychology – for it took me a while to see the point – was not accidental.

The internal opposition was the effect of a colonial knowledge.

That voice that whispers that psychology cannot have a word like African in front of it – although it can have American as an adjective – is of course a voice of the inner oppressor.

It is the inner coloniser’s voice against Africans as producers of knowledge, even knowledge to control their own lives. Hence, for me African psychology, which is to say African-situated knowledge, is resistance knowledge. It is imperative knowledge for self-determination and liberation. It is knowledge that makes sense, enables me to see myself clearly. Therefore, it is knowledge that is meaningful for living, besides being useful. Perhaps most beautiful of all it is knowledge that places me not just in the world in which I live as it exists but connects me to the people who need the knowledge I have. Whereas the coloniality of knowledge is intended to support colonial relations between people, where some of us are inside, the so-called “experts”, and the large majority are outside, excluded because they cannot read the colonial knowledges or barred from the knowledge game.

But even if they can and do read, it is common cause that they will be confronted by mystifying jargon that also works to exclude them.

As I have explained in several articles and my book The World Looks Like This From Here[8]Ratele, Kopano. The World Looks Like This From Here: Thoughts on African Psychology. (Johannesburg: Wits Press, 2019)., while there are of course differences in orientation for those who are not afraid to refer to themselves as African psychologists, what we have in common is that the knowledge we produce must, among several goals, reconnect us with ourselves and what happens in our society. Professors do not sit outside of society. We are part of society, including what goes on its traditional and social media platforms.

5

At the end, to return to the beginning, so that I might give it its due significance, I should clearly state that while the mere fact of teaching African psychology to younger students at a predominantly white university was a milestone, of course the content of the class was just as critical.

As I have indicated, I have always seen Nwoye as a disciplinarist, a fielder, a point he most explicitly made in an article in which he responded to one I had written a few years earlier.[9] Nwoye, Augustine. ‘Frequently asked questions about African psychology: another view.’ South African Journal of Psychology 51, no 4 (2021): 560–574; Ratele, Kopano. ‘Frequently asked questions about African Psychology.” South African Journal of Psychology 47, no. 3 (2017): 273–79. You can refer to me as an orientationist (or, as I said, situationist). Where he believes that African psychology is a discipline in the way African politics or African literature is, African psychology for me has always been about orientation, approaches or interpretation. Amid our debates, I felt that he and others who share the view were mistaken, but I also recognised that his view would most likely prevail because achievements would be easy to measure. Where a disciplinarist would possibly regard it as an achievement if a university was to install a professor of African psychology, that, in my view, would be a terrible achievement. I approach African psychology as a way of orienting ourselves in the world. The interpretation of reality (and dreams too). Angles of vision. You cannot have a professorship in an area called interpretation of reality. You cannot have a department called angle of vision. That implies that while I could happily teach in a department of African politics (or African history), if they would have me, I would not want to teach in a department of African psychology (or African sociology). The difference between the former group and the latter is in the nature of the object of study. That difference is what makes the difference in how we ought to think of African politics versus how we are thinking of African psychology.

In the four classes I gave in that first year I therefore wanted students to leave the classes with a better appreciation of the fact that interpretation is everything in how we approach psychological and social life. African psychology is about explaining, with the help of the red pill, the world from our location in the world. Knowing that our location does not offer us God’s eye-view of the world is the first lesson.

One can also say, in the context of psychological and social life, to be is to interpret. And interpretation means power over our lives. If you desire to govern others, you control their interpretations of the world.

I also wanted to nurture the view that all interpretations are always situated. At best, students would leave the lectures with a sense that interpretations emerge from understanding but also frame understanding. At the same time, any understanding, more so in the behavioural sciences, that omits a focus on enriching our self-understanding is gravely inadequate. Understanding, then, which includes self-understanding, and therefore the self-interpretation of social and subjective reality, offers us control of our own thinking, our emotions, our behaviour, and our lives. That in my view is one way to sum up why we cannot be happy with Western psychology when we can interpret the world for ourselves. That is what I wanted to teach and hoped I was able to do, even in some small measure. And that, I think, was part of the joy in having taught that class that year.

| 1. | ↑ | Nwoye, Augustine. ‘What is African psychology the psychology of?’ Theory & Psychology 25, no. 1 (2015): 96-116. |

| 2. | ↑ | Ratele, Kopano. ‘Four (African) psychologies.’ Theory & Psychology 27, no. 3 (2017): 313-327. |

| 3. | ↑ | The Chair was a 2021 Netflix series created by Amanda Peet, and Annie Julia Wyman and starring Sandra Oh, about the first woman of color, Professor Ji-Yoon Kim, to become chair of an English department at Pembroke University. |

| 4. | ↑ | Noel Chabani Manganyi is the first black person to receive a PhD in South Africa. For example, see Manganyi, N. Chabani. Apartheid and the making of a black psychologist: A memoir. NYU Press, 2016. |

| 5. | ↑ | Hussein Bulhan is a Somali psychologist. For example, see Hussein A. ‘Stages of colonialism in Africa: From occupation of land to occupation of being.’ Journal of Social and Political Psychology 3, no. 1 (2015): 239-256. |

| 6. | ↑ | Bame Nsamenang was a Cameroonian psychologist. For example, see Nsamenang, A. Bame. ‘Factors influencing the development of psychology in Sub-Saharan Africa.’ International Journal of Psychology 30, no. 6 (1995): 729-739. |

| 7. | ↑ | In South Africa, only 7% of adults have a tertiary education, and only 6% of 25-34 year-olds were tertiary educated (OECD, South Africa: Overview of the education system: EAG 2021). South Africa’s overall Gross Enrollment Rates (GER) for tertiary education is lower than GERs of comparable middle-income countries such as China, Malaysia, Mexico Russia but higher than for African countries such as Cameroon, Ghana, Mozambique and Senegal. For instance, in 2018, South Africa’s GER was approximately 24%, those of China was 50% and Russia’s 85%, and those of Ghana and Mozambique were 16% and 7% respectively (Khuluvhe, Mamphokhu and Elvis Ganyaupfu, Access to Tertiary Education: Country Comparison using Gross Enrolments Ratio. (Department of Higher Education and Training, Pretoria, 2021).; see also, Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey. Statistical Release P0318. (Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2020.) |

| 8. | ↑ | Ratele, Kopano. The World Looks Like This From Here: Thoughts on African Psychology. (Johannesburg: Wits Press, 2019). |

| 9. | ↑ | Nwoye, Augustine. ‘Frequently asked questions about African psychology: another view.’ South African Journal of Psychology 51, no 4 (2021): 560–574; Ratele, Kopano. ‘Frequently asked questions about African Psychology.” South African Journal of Psychology 47, no. 3 (2017): 273–79. |