IGNATIA MADALANE

From Paul to Penny: The Emergence and Development of Tsonga Disco (1985-1990s) Pt.2

Joe Shirimani

Born in KaN’wamitwa, a village in Tzaneen, Limpopo Province, Joe Shirimani came from a musical family. His father played the guitar and it was not long before young Joe picked up the instrument. This humble and soft-spoken musician, songwriter, arranger and producer leisurely related his story as we sat in his studio in Soshanguve, a township outside Pretoria.

During our conversation, Shirimani emphasized that he had grown up in a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society. Growing up in a multi-cultural environment was to influence Shirimani’s later work. While in high school, in 1987 he started a 7-piece band called Kimayos (Kind Masters of Youth Sound). It was with this band that Shirimani recorded his first demo. Their debut album, after a few hindrances, was released in 1989. The music recorded by the band was, according to Shirimani, disco or bubblegum.

I think I can call it disco but we used many languages because when I look properly, look at the way Pretoria is, it has many languages, Sesotho, Tswana, Sepedi, Ndebele, there is everything. It was not Shangaan disco,[1]The words Tsonga and Shangaan are used interchangeably here because Shangaan is another designation often used, sometimes problematically, for Tsonga people. The style is sometimes called Tsonga disco, other times Shangaan disco. The debate and controversy surrounding the two terms is beyond the scope of this article. For a brief overview of the controversy surrounding the use of these terms see the online article, ‘How Tsonga became Shangaan: The difference between Tsonga and Shangaan’ (2014). it was disco, it was like, you know Yvonne Chaka Chaka, Chicco, you know, it was that type of music. Some called it bubblegum at the time that was the kind of music we played. We were still young and so we were interested in music that would make people dance.

Interview 3 April 2009

After Kimayos, Shirimani worked with various groups such as Malume Pikipiki, Angola, The Crooners, and Chibuku before releasing his debut solo album Black is Beautiful in 1993 (Ncube 2000: 21). Since this album, Shirimani has released a number of hits including, “Gabaza” (a person’s name), “Nosi” (‘Bee’) and “Limpopo”. It was only when Shirimani went solo in 1993 that his music was placed within the Shangaan or Tsonga disco subgenre. About this he commented: “the definition for this Shangaan disco is that, disco meaning dance, pop music, Shangaan is put in there because of the lyrics and the way we sing is leaning on the side of Tsonga tradition” (Interview 3 April 2009).

Though Shirimani enjoys commercial success as a songwriter and performing artist, it is also through the work he does as a producer that he has made his mark on Tsonga disco. Two of Shirimani’s successful artists are Esta M of “Nawu” (‘law or tradition”) fame and the current holder of the ‘king’ of Tsonga disco crown, singer and songwriter Giyani Kulani Nkovane, known by his stage name, Penny Penny. He occasionally works with another Tsonga disco favorite, Chris Mkhonto, known by his stage name, General Muzka, and more recently, he took on a protégé Benny Mayingane, who won the Best Xitsonga most popular song at the 2012 Xitsonga Annual Music Awards.

Shirimani explicitly declared his centre collective status at a performance that took place at Phomolong, a village in Limpopo, on 20 March 2010. After the first song, while waiting for the second song to start, he declared to the audience: “Esta M is my child! Penny Penny is my child!” Besides writing songs and producing for these artists, Shirimani’s most important contribution is a peculiar bass sound that has become the defining feature of Tsonga disco. The bass sound created by Shirimani is identified by its richness, depth and sharpness. While keeping the consistency of the bass beat, he manipulates it so that it is the most dominant and most powerful sound in the song, making it texturally thick and acoustically deep.

Shirimani said he creates this bass sound through the application of various effects; he was reluctant to speak more about this trademark sound. However, he proudly pointed out that “kwaito singers want that sound and they have asked me for it but they won’t get it. They tried but they can’t get it right” (Interview 3 April 2009). This bass sound is present in most of Shirimani’s and Penny Penny’s music and it has come to symbolize Tsonga disco more than any other sound or feature of the music. The prominence and popularity of this particular sound was enhanced by the fact that Penny is considered by commentators and fans to be current king of Tsonga disco. The album The King vs The General (2009), produced by Shirimani and the late Rhengu Mkhari, is a confirmation of this with the General referring to the previously mentioned General Muzka.

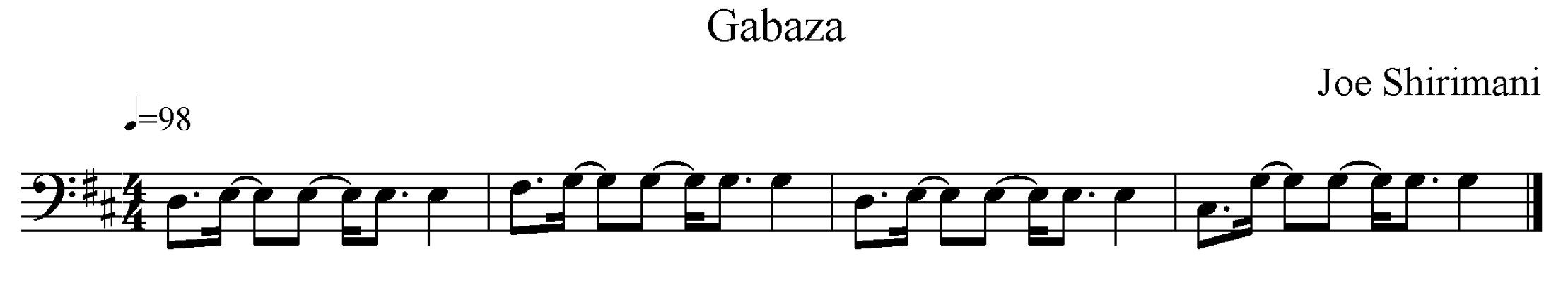

In the song “Gabaza” the bass line is as follows:

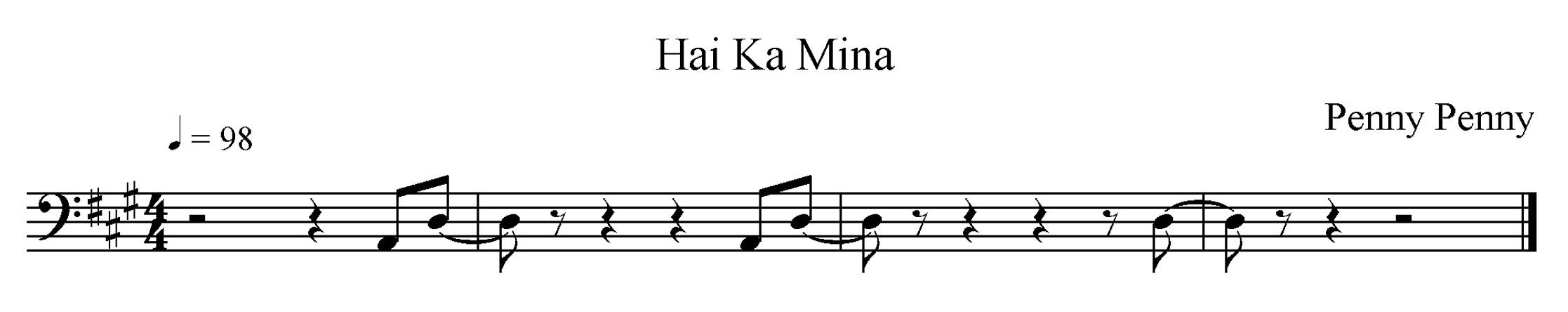

In Penny Penny’s “Hai Kamina” (“not in my house”), the bass line is as follows:

Shirimani’s bass motifs differ from those of Ndlovu and Teanet in terms of the texture and tone and also in that, while the latter often alter the bass line in minor ways when it appears later in their songs, Shirimani’s bass lines remain the same throughout: the above bass lines remain as they are for the entire song. However this does not mean that the bass appears non-stop as he makes use of instrumental breaks during which the bass line falls out of the mix. Elsewhere, the bass line remains while the other instruments drop out. These are all typical production techniques of global dance musics.

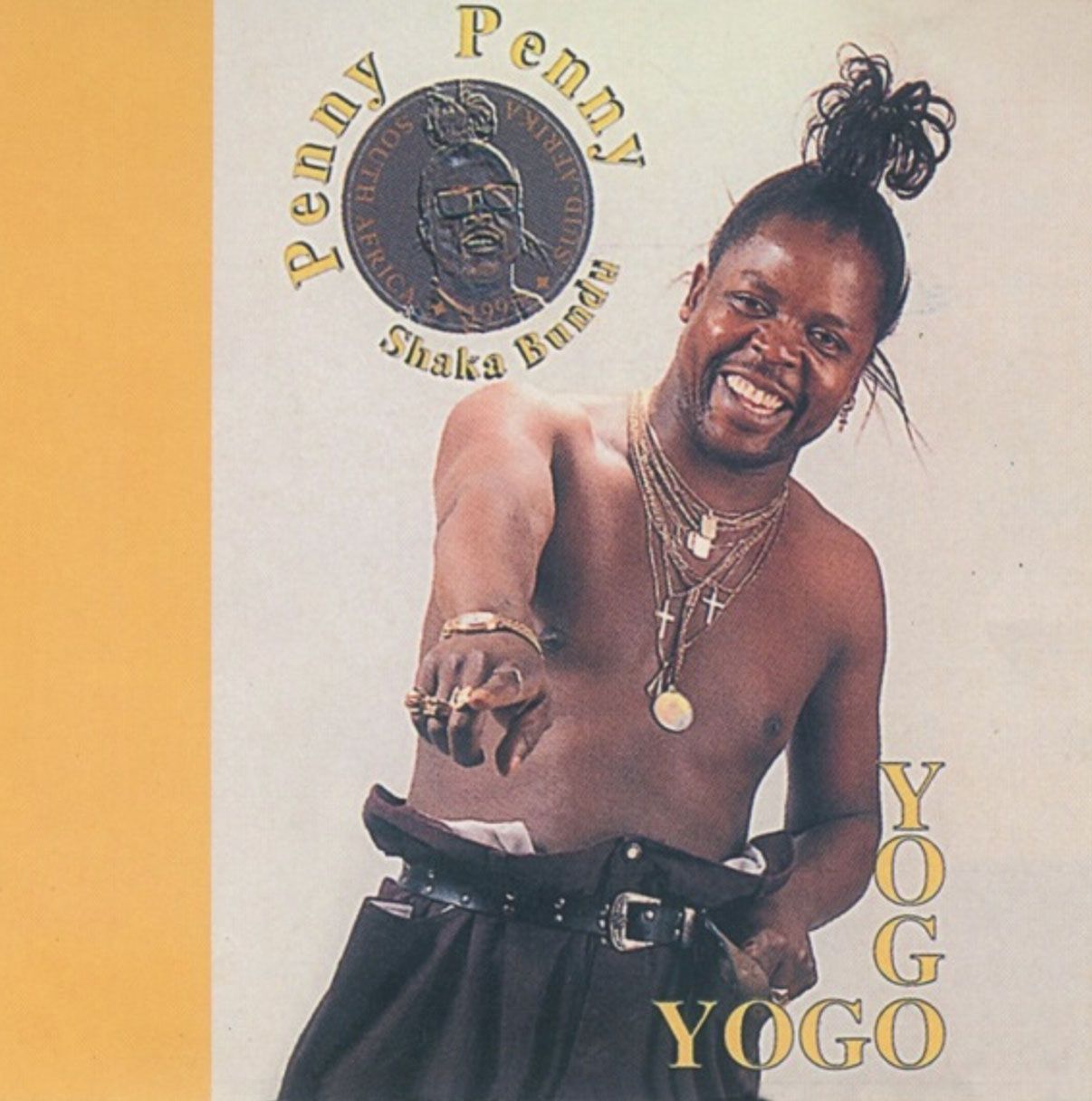

Penny Penny

Before further discussing Shirimani’s music, it is necessary to focus on Penny Penny as Shirimani produces most of his music.[2]I have paraphrased Penny’s story due to many English linguistic errors in his narration. Penny was born Giyani Kulani Nkovane in a village called Ximbupfe in Giyani, the capital of Limpopo. He was given the name Eric by the apartheid “government” (Penny’s words) when he applied for his pass in 1977. His father was a traditional healer who had twenty-two wives (though Mojapelo says there were sixteen, 2008: 145). He never went to school but was proud to say that he can read and write. Due to his father’s practice as a traditional healer, Nkovane grew up dancing Tsonga traditional dances such as muchongolo, xichayichayi, and xigubu.[3]See Thomas F Johnston articles for further reading on these dances. After the death of his father his family lived in poverty which led him to seek work on nearby farms when only 10 years old. He later worked in the mines at West Driefontein, Carletonville. It was here that he developed a serious interest in music, beginning with dancing. He later moved to Johannesburg where he danced in night clubs while selling vegetables on the streets for a living. While struggling to make a living, Nkovane began making demos and sending them to people with the hope of getting a foot in the music industry door.

After many rejections and disappointments, Nkovane was finally discovered by Shirimani while working as a cleaner at Shandel Music. It was Shirimani who transformed Nkovane into Penny Penny, the “king” of Tsonga disco. Majapelo writes that “Shirimani … taught him the tricks of the trade [and] before long [Penny] … was writing songs. His debut album Shaka Bundu achieved platinum status and the second one achieved triple platinum” (2008: 147).[4]Penny is also known as Shaka Bundu, but in the song of that name it refers to a pretentious relative.

In addition to his signature bass sound, Shirimani introduced other features to Tsonga disco that sets him apart from his precursors: “let’s say you look at Paul Ndlovu’s disco and Peta Teanet and look at Joe’s disco and look at Joe’s style, mine is different” (Interview 3 April 2009), and different it is. Like his predecessors he makes use of keyboard riffs, but Shirimani’s music is dominated by a sustained synthesized string sound. Sustained strings are a common feature of American and Tsonga disco, and in Shirimani’s music they seem to appear more constantly than in any of his predecessors’ music. For example in “Marabastad”, “Yandee” (the name of a person), “Khethile Khethile” (‘once you have chosen, you have chosen, i.e. there is no going back), “Mapule” (the name of a person), “Cheap Line”, and “Biya” (‘Beer’), the sustained synthesized strings appear almost throughout the pieces with few breaks.

Another synthesized sound that Shirimani has a fondness for is the steel drums. He admitted to liking the sound and therefore often uses it. A steel drum motif can be heard in “Marabastad” (from 1:18) which keeps recurring in the piece. Penny’s “Hai Kamina” (“Not in my house”) begins with the following synthesized steel drum motif:

The motif appears again later in the song and it is exemplary how Shirimani uses the synthesized steel drums in his music, as a short melodic line which keeps recurring at different intervals in the songs. In the same song, there appears another of Shirimani’s much loved synthesized sounds. The song begins with the steel drum motif supported by the hi-hat before the kick enters with a short synthesized conga rhythmic pattern. Penny’s powerful voice penetrates with the words “Do you?” This functions as a question, which is then answered by the following riff:

These stabs are played on electric bass saxophone, another of Shirimani’s favourite sounds.

The same sax sound can be heard in “Marabastad”, “Biya”, both from the album Nivuyile (1995), “Yandee”, “Sathana”, and “Dom Dom”, from the album, The Best of Joe Shirimani (2003).

William Hanks concludes that genre offers “a framework that a listener may use to orient themselves; producers to interpret the music; and a set of expectations” (cited in Gloag and Beard 2005: 72). This assertion is apparent at the above mentioned performance of Shirimani in Phomolong. Shirimani maneuvered through the expectant crowd towards the stage to the sound of his intro on the albums Miyela (Be still) and Tambilu Yanga (Matters of my heart) while the MC encouraged the crowd to welcome him. The intro track was then replaced by a dance track to which his dancers responded. After grabbing the microphone from the MC, Shirimani proceeded to the front of the stage where he began waving his hand up and down as if asking the audience to respond. This they did. With an unplugged microphone in hand, Shirimani began singing along to the backing track. The first song, “Hlamala” (A person’s name), was different from the style for which he is known. Its tempo is faster than most of his other material. Also, the song employs a kwaito technique of rhyming a few words over and over again. For the remainder of this track’s performance, Shirimani positioned himself further back from the front of the stage, giving the dancers the center stage, a clear expression that this piece was a dance track and therefore that dancing is the fundamental part of the performance.

The next song, “Tshelete” (‘Money’) did not sound like Shirimani’s usual work either; it too was faster and did not contain his signature bass sound. The audience seemed to be confused. There was very little screaming, shouting and clapping when he performed these two songs. It was after the second song that Shirimani officially introduced himself proudly proclaiming: “Penny i n’wananga (Penny is my child), Esta M is my daughter”. While waiting for his next track to begin playing, the audience started shouting, “Penny, Penny, Penny”.

After Shirimani formally introduced himself, the song ‘Nosi’ (‘Bee’) was played. The audience’s reaction proved the popularity of the song: screams were heard as the thumping, signature bass blasted out of the inadequate speakers. This song’s reception, compared to that of the first two songs underpins Holt’s statement in which he argues that “genre is not only in the music but also in the minds and bodies of particular groups of people who share certain conventions” (2007: 2).

While the signature bass sound, the electronic saxophone and steel drums distinguishes Shirimani’s music from that of Ndlovu and Teanet, the lyrical subject matter is similar to that of his predecessors. In both his and Penny’s songs, domestic, love, and social matters are common themes. “Dom Dom” (“stupid head”) challenges the domestic servitude stereotype. It is unusual practice among the Tsonga for a man to be involved in domestic chores as implied in Ndlovu’s “Khombo Ra Mina”. In “Dom Dom” Shirimani challenges this stereotype. He sings of people who call him stupid for helping his wife but when she slaves away for him no one says anything: “Ilodlaya mani?” (Who has she killed [to deserve such ill treatment and accusations of witchcraft])? Shirimani not only challenges men to help their wives at home but also defends women who are often victims of witchcraft accusations when their husbands show them too much affection.[5]Junod’s The Life of a South African Tribe addresses witchcraft practice among the Tsonga in detail (1962).

Written by Penny and Shirimani, “Hai Kamina” addresses the issue of educated and empowered women who become disrespectful towards their husbands.

Ho ni nese mina

A ka mani?

Hayi kamina

I am a nurse

In whose house?

Not in my house

Here women are reminded of their ‘place’ in the home, pointing out that even if they are educated; their authority is limited to the workplace. It is interesting to note how in “Dom Dom” Shirimani suggests equality in relationships, while “Hai Kamina” suggests a more submissive position for women. Such are the contradictions of the different worlds and audiences Tsonga musicians live in and address.

Some of the social issues addressed in Shirimani’s and Penny’s songs include the AIDS problem which South Africa faces. In “Ibola AIDS” (‘iBola and AIDS’) Penny cautions people to fear the disease saying that even bishops and leaders are scared of it. In “Hayi Kashi Nditshane” (‘Small dish’) Penny complains about false religious leaders who demand exorbitant amounts of money as offerings from their congregations. In “Education”, Penny encourages young people to put education first in their lives. Domestic or social issues, like in Tsonga traditional music, are an important subject in Tsonga disco song texts. This is in contrast to American disco which disregarded such issues and was more about “self, celebration, ecstasy and escapism” (Hamm 1988: 35; Barker and Taylor 2007: 236).

In addition to relying on love and domestic themes, as part of their social commentary, Shirimani and Penny also employed lyrics that affirm ethnic identity. There is a common belief that Shangaans used to hide their identity due to socio-cultural marginalization (see Madalane 2011). When political freedom came with its “unity in diversity” values, Shirimani used the opportunity to “uplift” Shangaans. Shirimani elaborated “Shangaans, we used to undermine ourselves. I am the one who helped to uplift us. It is me, with Penny, who helped Shangaans take pride in who they are’ (Interview 4 April 2010). Penny added, “Shangaans were hiding themselves, that’s when I got happy because I uplifted the Shangaans where they were. Others were making themselves Zulu; some were making themselves other things. But because I said Shangaan is English, Shangaans became proud, they came out. I was proud because of that song” (Interview 4 April 2010).

Other songs that relate to this type of ethnic mobilization include Shirimani’s “Bomba” (“Take pride”). This song from the Gabaza album of 1999, affirms Shirimani’s position on ethnic mobilization. In the song he takes pride in having achieved “uplifting” Shangaans or Tsongas, as Tsongas have now reclaimed their identity; they are no longer hiding and therefore encourage other ethnic groups to maintain their ethnic pride. It is in this song that he also encourages other people to take pride in their ethnic identity. This overt reference to ethnic mobilization and affirmation significantly alters the formerly apolitical and non-ethnically explicit nature of Ndlovu’s disco to a more succinctly ethnically aware subgenre. Tsonga disco thus became, during Penny Penny and Shirimani’s period, a medium for cultural expression afforded to them and encouraged by democracy and the “unity in diversity” discourse. It functioned as a tool to show cultural pride for a specific ethnic group, as opposed to Ndlovu’s music which lacked such overt sentiments.

Tsonga Disco in Society

In the article “In Defense of Disco”, Richard Dyer characterizes disco as being what he calls “romantic”, referring to the music’s ability to give its participants an out of body experience which he calls “ecstasy” (1979: 106). Though the romanticism of disco Dyer talks about refers in part to an emotional escape experience, Barker and Taylor describe a more physical or social aspect of disco as escape; arguing minorities, including gays, lesbians, blacks, hippies and Latinos, used disco as an escape mechanism from the injustices and prejudice of societies in the 1970s (2007: 236).

In Johannesburg, the early to mid-1980s possibly saw disco function in similar ways. Ndlovo’s producer, Peter Moticoe told how, although the 80s was a time of protest song because of the socio-political state of the country, people also needed to dance and have a good time, and disco provided the platform for this. SABC Media Librarian, Themba Mtshali pointed out how he and friends went to discos to dance, booze and womanize. Discos in Johannesburg, according to Mtshali and Moticoe, not only functioned as a place of escape for the ordinary man, but occasionally provided sanctuary for comrades. Moticoe shed a tear as he remembered how they sometimes hid struggle comrades with their instruments and often helped them cross the border to neighboring countries when they went on tour. He narrated how they sometimes hid the comrades within the drum kit and helped them cross the border to Swaziland when going there for performances. “Today these guys are big in the government, they hold big positions, yet they don’t remember us, to them we are just entertainers” (P. Moticoe Interview 4 May 2011).

Critical Analysis

A symptom of Bourdieu’s power, capital, and habitus concepts, the resultant labelling of this music is evidence of the lack of both social and economic capital by the musicians, thus resulting in their inability to have power over what they would like their music to be labelled. My interlocutors expressed frustration at the ethnic labelling of their music, citing major inconveniences such as not being playlisted on other South African radio stations because of the ethnic label. This further proves Bourdieu’s habitus concept in that, not only were the artists systemically disadvantaged socially and economically because of the apartheid system, they also lacked social and financial capital to independently have control over every aspect of their music. All the musicians discussed, during the period under discussion here, were at the time, for, recording, production, distribution, publishing, and marketing, relying on companies owned by foreign investors who were content to comply with the apartheid system’s policies. This also justifies the music being encouraged amongst the black population as disco was, according to Hamm:

By the mid-1980s, the grand media strategy theorized in the 1960s was finally in full operation. All of South Africa, and Namibia as well, was blanketed by a complex radio network ensuring that each person would have easy access to state-controlled radio service in his/her own language, dedicated to mould[ing] his intellect and his was of life by stressing the distinctiveness and separateness of ‘his’ cultural/ethnic heritage … The majority of programme time was given over to music, selected for its appeal to the largest possible number of listeners within that particular group, functioning to attract an audience to radio service whose most important business was selling ideology (1991: 169).

The state owned radio relied on record companies to provide the music and the record labels relied on the radio station for playing, publicizing their music thus increasing record sales. Thus, the relationshiop between the radio stations and the record labels was mutually beneficial, whereas for the musicians, it was seemingly that of what Bourdieu refers to as dominant/dominated, with the record label being the dominant while the musicians were being dominated. Though the musicians profited through gaining fame and income, compared to what the record labels made through their music and the musicians, their continued reliance on record labels proves that they remain dominated.

As a black recording artist myself, I can testify to the challenges of trying to autonomously make a living without the assistance of the various institutions such as the state-owned broadcaster and other companies. Even in post-apartheid South Africa, it remains a great challenge to succeed without the aid of these institutions for financial support, despite the advent of the internet. Thus, one could argue that the music produced by the musicians is a direct result of their socio-economic, cultural, political, and historical circumstances. It is important to note that though disco was played on black radio stations, it was not played on the white radio stations.

Principal technician at the SABC, Rob Lens, and senior archivist for Sound Restoration at the SABC, Marius Oosthuisen, both told me how disco was not played on the white radio stations because it was considered “evil”. Oosthuisen pointed out that they never heard disco on air but bought the records from an Indian shop out of town. ‘You could not find disco in the outlets in town such as OK’ (M. Oosthuisen, 28 January 2011). Oosthuisen and Lens elaborated that because there was a lot of falsetto (for example in the Bee Gees sound) in disco, it was considered unmanly ‘to sing like that’, and was thus associated with gay culture; at the time homosexuality was illegal in South Africa (ibid.). While the national broadcaster could not feed its own people ‘demonic’ music, it felt the music was appropriate for the ‘natives’. First, because it was dance music, it was believed that ‘natives will respond to rhythm [rather] than harmonic or melodic elements’ (Hamm, 1991: 150). Second, disco’s texts were apolitical and therefore met the Publications Board requirements for music to be played on air for black South Africans. South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela referred to disco as a ‘social tranquilizer’: ‘I love you, baby, we’ll boogie all night. Shake your money-maker. Do it to me tonight. Do it to me three times. Now we are trapped, man. Disco is a social tranquilizer; you don’t recognise other things. We can’t boogie for the whole year’ (cited in Ansell, 2005: 198).[6]See Madalane (2011)

By ‘other things’, Masekela was referring to the political situation in the country in the 1980s. By this time ‘the struggle [had] intensified, censorship had been stepped up, even from the severe restrictions of the 1970s and woven more tightly into the structures of the police state’ (Ansell, 2005: 197). Musicians whose music was political went into exile and those who remained in the country had to comply with state policies or their music would be banned. Disco’s non-political nature gave it a free pass with the state broadcaster, thus becoming an instant hit and before long, black South African musicians were appropriating disco into their own music practices (Hamm 1988: 33).[7]See Madalane (2011). This can be seen in the music of all the musicians discussed above. Though some of their lyrics may refer to ethnic identity, like that of Shirimani and Penny, none of the music discussed is political. Therefore, rather than the musicians discussed being successful because of their artistic mastery, it is evident that the state broadcaster had influence over who became a success and who did not, which then again highlights the power relation between the state and the musicians, i.e, the music is the result of the social infrastructure.

Conclusion

Ndlovu’s music career seems to epitomize the fortunes of disco itself. He emerged into the music industry, quickly became a national icon and tragically died in the second year of his solo career. However, like the impact of disco, whose heyday was short-lived but with a legacy that continues to live on in other popular music such as house, hip hop, rap and techno (Bidder 2001; Brewster and Broughton 1999; Snoman 2004), Ndlovu’s legacy lives on in the rhetoric of today’s Tsonga disco artists. These artists may have created their own musical identities, they may no longer necessarily reference Ndlovu’s sound in their music, but Tsonga disco remains their forefather.

As a subgenre, Tsonga disco attests to Holt’s assertion of popular music genre being fluid. Though the label has remained, it is clear from the discussion above that the music continues to take on new shapes. Hamm’s cross-fertilization also resonates throughout these examples as it has been observed that much of Tsonga disco uses both domestic and international genres while remaining apolitical. It is only the imitation that seems to be absent in Tsonga disco as none of the musicians have ever directly mimicked American musicians. Importantly, the discussion also reveals how popular music is influenced by socio-political circumstances and vice versa.

In this article I sought to trace the emergence of Tsonga disco. Further, I discussed the musical techniques employed by the by the musicians. Lastly, I argued that the music is influenced by the socio-political infrastructure. My findings include that, Ndlovu was the first musicians to be labelled and marketed as a Tsonga disco musician. Peta Teanet, following Ndlovu’s death, made reference to Ndlovu by citing some of the musical motifs found in Ndlovu’s music. Thus, he acknowledged Ndlovu’s influence on him though he paved his own path and had his own idiolect. Though Joe Shirimani and Penny Penny continue to use some of the musical elements found in Ndlovu’s music, they also have paved their own music route and remain unique in their own right. Lastly, this article has also presented the views of the musicians and how they view their music, how the music has been developed, and how socio-political enviroment played a role in how the music developed. There remains much space for further inquiry, such as investigation of audience reception, detailed music analysis, and perspectives on the music, especially with regard to the subject of ethnic mobilization.

Read Part 1 of this article here.

Allen, Lara V.

2004 “Kwaito versus Crossed-over: Music and Identity during South Africa’s Rainbow Years, 1994-1996.” Social Dynamics, 30(2): 82-111.

2003a “Commerce, Politics, and Musical Hybridity: Vocalizing Urban Black South African Identity during the 1950s.” Ethnomusicology, 47(2): 228-249.

2003b “Representation, Gender and Women in Black South Africa Popular Music, 1948-1960.” PhD Dissertation: University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

Allingham, Rob

1999 “South Africa: Popular Music, the Nation of Voice.” in S. Broughton et al, eds. World Music: The Rough Guide, London: The Rough Guides. 638-657.

1994 “Southern Africa.” In S. Broughton et al, eds. World Music: The Rough Guide, London: The Rough Guides. 371-389.

Anderson, Muff

1981 Music in the Mix: The Story of South African Popular Music. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

Ansell, Gwen.

2004 Soweto Blues; Jazz and Politics in South Africa. New York: Continuum.

Ballantine, Christopher

1989 “A Brief History of South African Popular Music.” Popular Music, 8(3): 305-310.

Barker, Hugh, Yuval Taylor,eds.

2007 Faking it: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music. New York: W.W.Norton.

Beard, David, Kenneth Gloag

2005 Musicology: The Key Concepts. London and New York: Routledge. Bidder. Sean

2001 Pump Up the Volume: A History of House. London: Channel 4 Books Borthwick, Stuart, Ron Moy

2004 Popular Music Genres: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre

1984 Disticntion: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

1986 “Forms of Capital.” In J. Richardson, ed. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, New York: Greenwood, 241-258.

Brackett, David

2005 “Questions of Genre in Black Popular Music.” Black Music Research Journal, 25(1/2): 73-91.

Broughton, Simon, Mark Ellingham, Richard Trillo, eds.

1999 World Music: Volume 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East: The Rough Guide. London: Penguin Books.

Burnim, Mellonnee V., Portia K. Maultsby, eds.

2006 African American Music: An Introduction. New York and London: Routledge. Coplan. David B

2007 In Township Tonight! Three centuries of South African Black City Music and Theatre, 2nd edition. Auckland Park: Jacana Media.

2005 “God Rock Africa: Thoughts on Politics in Popular Black Performance in South Africa.” African Studies, 64(1): 9-27.

1985 In Township Tonight! South Africa’s Black City Music and Theatre. New York: Longman Publishers.

Drewett, Michael, Martin Cloonan, eds.

2006 Popular Music and Censorship in Africa. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Dyer, Richard

1979 “In Defence of Disco.” Gay Left: A Gay Socialist Journal, 8: 20-23.

Greenfell, Michael

2008 Pierre Bourdieu: The Key Concepts. Stocksfield: Acuman.

Hamm, Charles

1991 “The Constant Companion of Man: Separate Development, Radio Bantu and Music.” Popular Music, 10(2): 147-173.

1988 Afro-American Music, South Africa, and Apartheid. New York: Institute for Studies in American Music.

Haupt. Adam

2008 Stealing Empire: P2P, intellectual property and hip-hop subversion. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Holt. Fabian

2007 Genre in Popular Music. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press

Johnston, F.T.

1974 “The Role of Music in Shangana-Tsonga Social Institutions.” Current Anthropology, 15(1): 73-76.

1973a “The Social Determinants of Tsonga Musical Behaviour.” International Review of Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 4(1): 108-130.

1973b “The Cultural Role of the Tsonga Beer-Drink Music.” Year of the International Folk Music Council, 5: 132-155.

Junod, Henry A.

1962[1912-13] The Life of a South African Tribe. New York: University Books Inc.

Madalane, Ignatia

2011 “Ximatsatsa: Exploring Genre in Contemporary Tsonga Popular Music.” Masters in Music Dissertation: University of the Witswatersrand, Johannesburg.

Meintjes, Louise

2005 “Reaching Overseas: South African Engineers, Technology and Tradition.” In Paul D. Green and Thomas Porcello, eds. Wired for Sound: Engineering and Technologies in Sonic Culture, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. 23-46.

Mhlambi, Thokozani

2004 “Kwaitofabulous: The Study of a South African Urban Genre.” Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa, 1: 116-127.

Mojapelo. Max

2008 Beyond Memory: Recording the History, Moments and Memories of South African Music. Sello Galane, ed. Somerset West: African Minds.

Negus. Keith

1999 Music Genres and Corporate Cultures. London and New York: Routledge.

Shaw. Jonathan

2010 [2007] The South African Music Business. Johannesburg: Ada Enup Snoman. Rick

2004 The Dance Music Manual. Tools, Toys and Techniques. Oxford: Burlington MA Focal.

Starr, Larry, Christopher Waterman

2006 American Popular Music: The Rock Years. New York: Oxford University Press

Steingo, Gavin

2005 “South African Music After Apartheid: Kwaito, the “Party Politic,” and the Appropriation of Gold as a sign of Success.” Popular Music and Society, 28(3): 333-357.

Ngobeni, Obed & Kurhula Sisters

1983 Kuhluvukile eka “Zete”, Heads Music Ent: LP EAD 1008 (CD).

Ndlovu, Paul

2009 The Unforgettable, Gallo Records: CDTIG 426 (CD).

2002 Paul Ndlovu’s Greatest Hits, Gallo Record Company: CDTIG401 (CD).

Penny Penny.

2007 Tamakwaya 8, Xibebebe, Cool Spot Productions: CDLION112 (CD).

2007 Shanwari Yanga, Cool Spot Productions: CDLION113 (CDN) (CD).

1996 La Phinda Inshangane, Shandel Music: CDSHAN 69D (CD).

1995 Yogo Yogo, Shandel Music: CDSHAN 49R (CD).

Shirimani, Joe.

2007/8 Tambilu Yanga, Shirimani Music Productions: CDSMP002 (CDM) (CD).

2003 The Best of Joe Shirimani, BMG Africa CDBMG: (CLL) 3005 (CD).

1995 Nivuyile, Paradide Music/BMG Records Africa: CDPTM(WL) 120 (CD).

Summer, Donna

2002 The Universal Masters Collection, Universal Music: GSCD 437 (CD).

1994 Endless Summer: Donna Summer’s Greatest Hits, Polygram Records: FPBCD047 (CD).

Teanet, Peta.

2008 King of Shangaan Disco, The CCP Record Company: CDMAC(GSB) 205 (CD).

2004 The Best Of, Gallo Record Company: CDGSP 3061 (CD).

1999 Greatest Hits, Mac-Villa Music (Pty) Ltd: CDMVM 512 (CD).

1995 Double Pashash, RPM Record Company: CDJVML 132R (CD).

Various Artists.

2008 Reliable Afro-Pop Hits, Gallo Record Company: CDGSP 3142 (ADN) (CD).

Interviews by Author

Lens, Rob. Johannesburg , South Africa, 28 January 2011.

Masilela, Lulu. Johannesburg, South Africa, 23 March 2010.

Moticoe, Peter. Soweto, South Africa, 4 May 2011.

Mtshali, Themba. Johannesburg, South Africa, 28 January 2011.

Nkovani, Eric [Penny Penny]. Pretoria (Tshwane), South Africa, 4 April 2010.

Oosthuisen, Marius. Johannesburg, South Africa, 28 January 2011.

Shikwambana, James. Polokwane, South Africa, 12 April 2009.

Shirimani, Joe. Pretoria (Tswane), South Africa, 3 April 2009.

| 1. | ↑ | The words Tsonga and Shangaan are used interchangeably here because Shangaan is another designation often used, sometimes problematically, for Tsonga people. The style is sometimes called Tsonga disco, other times Shangaan disco. The debate and controversy surrounding the two terms is beyond the scope of this article. For a brief overview of the controversy surrounding the use of these terms see the online article, ‘How Tsonga became Shangaan: The difference between Tsonga and Shangaan’ (2014). |

| 2. | ↑ | I have paraphrased Penny’s story due to many English linguistic errors in his narration. |

| 3. | ↑ | See Thomas F Johnston articles for further reading on these dances. |

| 4. | ↑ | Penny is also known as Shaka Bundu, but in the song of that name it refers to a pretentious relative. |

| 5. | ↑ | Junod’s The Life of a South African Tribe addresses witchcraft practice among the Tsonga in detail (1962). |

| 6. | ↑ | See Madalane (2011) |

| 7. | ↑ | See Madalane (2011). |