ZIYANA LATEGAN

Invention as Ideological Reproduction

Taiye Selasi once wrote that “[Virgil] Abloh’s blackness, as the possessive implies, belongs to Abloh. It is his possession, his invention, in so many ways a work—one of his works—of art.”[1] Taiye Selasi, “How to Be Both.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 131. According to Selasi’s portrait, Virgil Abloh’s blackness is dissimilar to ‘black’, the racial category constructed by the American racial schema, because it “rejects absolutes.”[2]Ibid.i Abloh’s blackness is not something that he can escape, but neither can he be reduced to it. In Selasi’s retelling, Abloh opened his Spring/Summer 2019 collection show by sending seventeen black models down a Parisian runway in a world built on the cornerstone of beauty (read: whiteness). It need not be overstated that the world of high fashion necessarily relies on exclusivity (excluding as the conditional operation) to exist. Any determination of judgment occurs only by way of a very tightly coordinated elite at the core affording and withholding credibility. Decisions on the relevant and the beautiful are directly determined by what is excluded from these categories—‘The Fashion World’ would have no basis outside of this method of taste making. Abloh knows first-hand that in the world of fashion, “race is the elephant in the room,”[3]Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, “Virgil Abloh: A Hundred Percent As Told to Anja Aronowsky Cronberg,” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica, 2019, 150. but he recognizes, simultaneously, that “part of the reason as to why I think I’m here is that I’ve accepted the reality and then been able to put it aside to get on with my work.”[4]Ibid.ii

Abloh is insisting, as Selasi has argued, on ‘being both’—both black and not black. Considering Abloh’s work, this is not only a case of code-switching as a mechanism of survival and success, or a double consciousness, although it certainly is that. Abloh tells us, “I’m a black kid, I identify with white kids, am I either? Maybe I’m somewhere in between.”[5]Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Accessed December 8, 2019] The in-between is Abloh’s playground, it is the philosophy behind his brand ‘Off-White’[6]Off-White is Abloh’s design house based out of Milan formed in 2013 as “defining the grey area between black and white.”[7]Off white/ [Accessed December 10, 2019] The middle space, the interstitial, the contradictory, the out of context, this is the birthplace of Abloh’s creative vision. As ‘the busiest man in fashion,’ Abloh is known as a multi-hyphenate artist: designer-artist-engineer-architect-deejay-influencer. The orientation of the polymath allows for a traversing of boundaries, and a privileged access to various contexts with a wider range of tools and materials. Abloh is the newly conceived Renaissance Man. In this regard, his collaboration with the Musée du Louvre in a special exhibition honoring the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci on the 500th anniversary of da Vinci’s death by designing a capsule wardrobe honoring the Renaissance artist, was especially fitting. When asked about his collaboration with the Louvre, Abloh referenced the multi-hyphenate nature of da Vinci’s practice as an inspiration, positioning himself too as something of a Renaissance man:

It’s a crucial part of my overall body of work to prove that any place, no matter how exclusive it seems, is accessible to everyone. That you can be interested in expressing yourself through more than one practice and that creativity does not have to be tied to just one discipline. I think that Leonardo da Vinci was maybe the first artist to live by that principle, and I am trying to as well.[8]Gabrielle Leung, Off-White & Musee du Louvre Collaborate on Leonardo da Vinci-Indebted Capsule Collection, 13 Dec, 2019. [Accessed December 30, 2019]

Abloh is known for his wide-ranging expertise and his capacity to use the tools of one field to tinker with the questions and problems of another. He also has the skill and wherewithal to apply this cross-pollination of ideas vertically—that is, to various strata within a field. The obvious example is the elevation of streetwear to the realm of luxury. Added to this is his unforgettable sold out opening for rapper and performer Travis Scott’s 2017 Bird’s Eye View Tour, when Abloh the DJ mixed Miles Davis’ “So What” with the Migos.[9]Virgil Abloh opening set “BIRDS EYE VIEW” Tour, 2017 [2:25]

There is no doubt that Abloh is at the helm of the American cultural scene. In 2019, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago presented Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech,” the first major mid-career retrospective of Abloh’s work. The exhibition traveled to Atlanta’s High Museum of Art in November 2019 and was due to appear at the Institute for Contemporary Art Boston in July 2020. In 2017, Abloh collaborated with esteemed activist and artist Jenny Holzer for a show at Pitti Uomo in a politically charged intervention to highlight the plight of refugees.

Notably, the invitation to the show took the form of an orange T-shirt bearing the instructions for how to put on a life vest, and a line taken from an Iranian writer who fled for Europe, Omid Shams, “I WILL NEVER FORGIVE THE OCEAN” in capitalized Helvetica typeface between quotation marks.[10]Susanne Madsen, Virgil Abloh on Getting Political with Jenny Holzer, 16 June 2017 [Accessed December 11, 2019] In 2018, Abloh secured the position of artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s men’s division. Abloh has collaborated with major corporations like Nike, the European furniture brand Ikea, the bottled water company Evian, the global ‘humanitarian’ aid organization UNICEF, to name a few. In 2018, Abloh was declared one of Time’s 100 most influential people, acquiring a profile entry by artist and collaborator, Takashi Murakami.[11]Takashi Murakami, Virgil Abloh, 2018 [Accessed December 9, 2019] Abloh was also responsible for Serena Williams’ get-up in her Nike x Abloh gear for the French Open a year ago. At this stage of his career, Abloh has acquired every necessary co-sign in almost every field of cultural expression.

At first glance, it appears to be a remarkable feat: to overcome all manner of limit, and find therein a multitude of contradictory spaces, each a container for a boundless and infinite creative potential. Is this not the absolute freedom, the opening up required for creating, for a true unfettered imaginative exploration? This is a space of invention, of making the world, of making oneself, of being.

Here there is no limit.

Except the one real limit that must constantly be “set aside”.

***

In a postmodern moment where everything seems to be overcome by a multitude of things expressing no overall unity, it would be difficult to maintain that all difference is contradiction.[12]Mao Zedong, On Practice and Contradiction, London & New York: Verso, 2007, 74. But let us posit that there is a graded scale of difference, and after having crossed some threshold of distinctness, difference becomes openly contradictory. The weakest difference, according to Badiou, is simply the difference between a thing and itself in a different place, at its most elementary, the space between something and itself.[13]Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject, London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2013, 24 This level of difference is everywhere in Abloh’s work in his reference to the readymade, the copy-paste methodology characteristic of internet culture. We could argue that the weakest difference is not weak at all, since the placing of an object in a different context produces an alienation from this context, and this alienation, according to Arthur Jafa, “produces a very particular kind of energy,”[14]Arthur Jafa & Greg Tate, Hammer Museum, 5 July 2017 [Accessed January 13, 2020] that Marcel Duchamp was able to understand. Abloh has credited his use of the readymade object (editing it only 3-5%) to Duchamp in an unsurprising referential gesture given that Duchamp’s readymades are themselves taken from the introduction of the ready-to-wear garment in fashion. As per Jafa’s note, the black body is the object-out-of-place. Out of context everywhere. Seventeen black bodies on a Parisian runway cannot be a testament to black-as-beautiful appreciated by a changing and more open-minded consumer class, as much as it is a testament to the violence of placement, placing objects in contexts in which they are necessarily and conspicuously out of place. Unbeknownst to Abloh,

these bodies must remain outside of this world if their appearances in it are to be remarkable.

The idea that one needs to have an appreciation for the contradictory in order to exist in today’s world is an avowed position Abloh adopted, in part at least, from Rem Koolhaas.[15]Virgil Abloh. “Theoretically Speaking” lecture, Rhode Island School of Design, 2 May 2017 [Accessed January 20, 2020] Given Abloh’s playfulness, and his injunction to “question everything,” Michael Rock has argued that Abloh’s method is primarily dialectical. Rock writes, “if the dialectic, then, is not a formula but a method of study, the simple fact of Abloh becomes a way to understand the interrelationships and contradictions that face contemporary design.”[16]Michael Rock, “The Edge of Center.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 143. Rock keeps pushing his hopeful dialectical materialist line, going so far as to splatter Abloh with a Soviet crimson:

A dialectical method should lead to a new synthetic practice, the goal of which is not interpretation but change: resolving of dialectic opposition results in tangible advancement. Quantitative change leads, over time, to qualitative change—changing things will eventually alter states of consciousness.[17]Ibid.iii

For anyone in Abloh’s position, the world appears as a totality comprising multivalent interrelated forces that are constantly shifting, a world that Abloh is indubitably a reflection of. Abloh speaks of the world of design as being a space without boundaries, where everyone has the capacity to think across and between disciplines, a design space that is the most democratic it has ever been; he says, “there’s a tremendous amount of freedom right now, to be free and to design a better world.”[18]Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Ac- cessed December 8, 2019]

Abloh’s contradictions never manage to rub up against one another in ways that show any signs of struggle. Accurately, there is a totality with a plenitude of contradictions, but for Abloh these contradictions require sitting in more than overcoming. What we are offered is a postmodern multitude of difference, simply an eclectic mix of things haphazardly bouncing off each other, from one idea to the next. He blurs rather than sharpens.

There is a weakest difference, but there is no upper limit to difference.[19]Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject, London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2013, 24. The weakest contradiction, the place of representation, is the extent of the meaning of contradiction in Abloh’s lexicon—the pleasure derived from having your expectations subverted. An openly conflictual contradiction however can be understood as two things in relation, each one requiring the other in order to exist, but at the same time, destroying the other in its effort to affirm itself. This level of contradiction appears nowhere in Abloh’s work, nor in his mode of criticism. Contradiction cannot be univocal if we concede to the complex structure of the whole—contradiction is “complexly-structurally-unevenly determined.”[20]Louis Althusser, For Marx. London and New York: Verso, 2005, 209. But for Abloh, it would seem that things are placed in opposition not by virtue of their contradictory nature (in some cases they certainly are antagonistically contradictory). Rather, they appear to be positioned as oppositional simply because they are distinct: purist vs tourist, black vs white, luxury vs streetwear. An invented sense of controversy resting on an abundance of imagined diversity, never determined by an already existing world of power relations that determine the degree of dominance that one aspect of a contradiction might have over another. Abloh clarifies:

I’m throwing a Molotov cocktail at the temple, but in a non-antagonistic way. I’m not punk; I’m not trying to overthrow the temple. The Molotov cocktail is just being there after starting the race from the furthest position.[21]Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, “Virgil Abloh: A Hundred Percent As Told to Anja Aronowsky Cronberg,” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica, 2019, 149.

Imagine yourself in the heat of the riot against the Master, a gasoline bomb floats mid-air slow motion above a sea of chaos. How could it ever be non-antagonistic?

Of his collaboration with Holzer, Abloh has stated that the “work is weighted. It’s not just fashion for fashion’s sake,”[22]Susanne Madsen, Virgil Abloh on Getting Political with Jenny Holzer, 16 June 2017 [Accessed December 11, 2019] appearing to make a commitment to something. Abloh’s method of critique—to question everything—is illustrative of a larger concern. Today, criticism is incorporated into the capitalist ethic, monetized and weaponized, packaged and sold by celebrity intellectuals, academics, artists, themselves ‘influencers’ in a paid partnership with a system of personal branding and a constantly consuming audience with an insatiable appetite. Finally, everyone has a ‘voice,’ everyone can contribute to a debate, the social sphere has been democratized.

Of course, there is no greater way to hide a totalitarian structure than behind its very opposite, the appearance of democracy.

More than mere incorporation, criticism is foundational to the social body. This overproduction and proliferation of criticism is sanctioned and incentivized. The limits of what we can question, of how we can question, are thus important to investigate. We could not have wished for a more exemplary product of ideology in this ravenously unequal and increasingly totalitarian American cultural sphere—auto-criticism included—than the multi-dimensional Virgil Abloh. Non-antagonistic critique is the brand that this age has engendered. It is when we think of ourselves as outside of ideology that we are most embedded in it.[23]Slavoj Zizek, ed. Mapping Ideology. London & New York: Verso, 2012.

“That’s why everyone is mesmerised by it [blackness]. And it’s not anti-capitalist or pro-capitalist, it exists outside the logic of capitalism.”[24]Arthur Jafa interviewed by Virgil Abloh in i-D, 16 September 2019 [Accessed December 10, 2019]

Power, in its rapacious, omnipotent, global incarnation, determines its opposition just as much as it determines its outside. The outsideness of blackness, its inexistence, is the possibility condition. The primary contradiction is repeatedly repressed. Misrecognition of the outside as a free space of creativity and invention, instead of as a part of the most fundamental contradiction in the socio-historical moment, ie. race, is precisely to avoid—or render impossible—a concrete analysis of concrete conditions. But how is it possible to think a new world from inside this one, when our inventions, like our bodies, are theirs?

***

What of the garments? The most notable Off-White garments are immensely interesting. Many garments are presented as unfinished products in order to welcome the user into the design process or to reveal the process of design making. An Off-White leather purse includes a broken circle printed on it, with the instructions cut here, but the cut remains unmade.

The design incorporates the shifters of the ‘sewing program’ into the final product. The shifter in this instance is a code usually employed as the transitional language mediating the movement from the technological garment to the iconic garment, “situated midway between the making of the garment and its being, between its origin and its form, its technology and its signification.”[25]Roland Barthes, The Fashion System. California: University of California Press, 1990, 6. In this instance the transitional language is printed on the garment, no longer used for its traditional transitionary function, in its new placement it acts as part of the form. The rearrangement of codes offers us a backstage view of the process of making, the purse is both what it is and what it should become. The artifact no longer hides anything from us, we are seemingly presented with reality as such. Again, the veil is removed, we are meant to have escaped the trappings of ideology that obscure the real nature of the way things are really made. But the shift in shifters hides more than it reveals—more sinister than the concealment of the social relations of production found in the finished commodity, the unfinished commodity conceals even further its act of concealment.

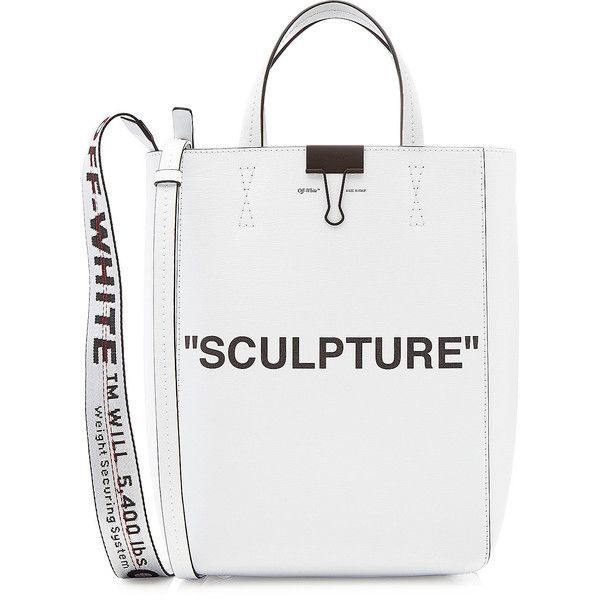

Other Off-White garments are recognizable because they appear uncannily generic. The famous Off-White dress is a plain black mid-calf long-sleeved skewed neckline dress with the world “DRESS” printed vertically, in Helvetica along the front edge. On first sight, the garment itself might strike you as unremarkable. Deliberately so. A typical Off-White “QUOTES” garment is the combination of a minimalist designed clothing item plus its signifier in the neutral capitalized Helvetica typography between quotation marks, a gesture emblematic of what Abloh would term the “post postmodern”. The unit operates both in a world of garment design and construction, as well as a syntactic world of language, a heavily textual component forms part of the technological structure of the garment.[26]In Barthes’ The Fashion System, he makes a distinction between the technological, iconic, and verbal structures of a garment. My concern here is with the technical insofar as it is also textual, rather than the written. Taken as a whole, the item itself mimics a Saussurean sign: for every signified, its signifier.

The sign, displayed as the garment, calls to attention the arbitrariness of language. Abloh asks us: outside of the mechanisms of use and convention, what transcendental connection exists between the word “DRESS” and the actual dress bearing the word? There is none. This is the place where all critique commences, “why is something the way it is and not some other way? And who decides that it be this way?” Over and above the use of irony as a contemporary method of creative expression,[27]Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Ac- cessed December 8, 2019] the questions leveled by the series of garments with “QUOTES” are provocative because they perform the first principle of all critique. Often the item bearing its signifier printed in capitalized Helvetica font does nothing more than call into question the construction of the sign, the recognition that our language is inherited and we are bereft of the capacity to point to their author, whose authority is nevertheless illegitimate. But the items of this category go beyond the function of mere semio-political critique.

Abloh authorizes and invents a sign with pieces like the printed text “SCULPTURE” on a leather handbag. By way of explaining the use of quotation marks, Alec Leach noted that:

when words are surrounded by speech marks, their validity is in question. By presenting words as citations, Abloh is taking them out of context, and questioning their seriousness. When he puts “Sculpture” on the side of a handbag, he’s provoking the viewer. What’s the difference between a handbag and a piece of art, really?[28]Alec Leach, Why Does Virgil Abloh Put Everything in “QUOTES”? 30 August 2017 [Accessed December 15, 2019]

The gesture cannot simply be dismissed as a clever use of irony. Instead, this work, much like the wallet bearing the signifier “FOR MONEY,” is attempting to offer us not the possibility of considering the handbag as an example of a sculptural object for aesthetic reflection (because, as Leach asks, why not?), going even further, the signifier functions to redefine the concept itself.

This designation of a new signifier onto something readymade, attached to a minimalist design, shifts the sign from being a garment in a collection, to reestablishing the ideal Platonic form of the garment, or at least its closest approximation. This is merely one instance of “where the alteration of the signifier occasions a conceptual change.”[29]Ferdinand de Saussure, “Course in General Linguistics.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, edited by Vincent B. Leitch, New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2018, 836. Stripped to an appearance of its most bare, Abloh materializes the Platonic ideal, he offers us a new ideal form itself. The practice of signification does the declarative work of deciding that the bag is “sculpture,” declaring the dress to be the dress. In appearance, the prototype is only formal, presented as the original form, purely given, unencumbered by a “surplus expressivity.”[30]Arthur Jafa interviewed by Virgil Abloh in i-D, 16 September 2019 [Accessed December 10, 2019] The relationship is not merely that between the thing and its name, as Saussure is at pains to remind us, the sign is the unity of concept and sound-image. Accordingly, the combination of sound and thought “produces a form, not a substance”.[31]Ferdinand de Saussure, “Course in General Linguistics,” 831. In a strange paradoxical performance, Abloh has invented a series of pure forms, rather than garments.

Does Abloh invent anything at all? If it can be said that Abloh has materialized form itself, in which all dresses are mere iterations of the ubiquitous immediately recognizable Off-White dress, and it is also the case that the universal ideal form in the social is merely a misnomer for the white bourgeois Euro-American ideal, then what is being created is no more than the reassertion of the dominant. Yet again, what appears as invention is no more than ideological reproduction.

“Pure form is, then, pure violence.”[32]Calvin Warren, “The Catastrophe: Black Feminist Poethics, (Anti)form, and Mathematical Nihilism,” Qui Parle, vol. 28, no. 2, December 2019, 363.

Of course, the value of the sign is determined by its environment, and in a way, Abloh’s critique lands equally on the conventional use of words, on the battle for the commonsense, as it could on the interdependent whole that order the signs, or make the series of signs sensible. Here, the whole is not limited to the linguistic system, but extends to the environment of creative design, the contemporary culture industry writ large, the governing relations of consumption-production-circulation and its necessary domain of democratized advertising.

It is as if Abloh has given us ideology glasses (from Slavoj Žižek’s treatment of the 1988 American Sci-Fi Horror They Live)[33]Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. Directed by Sophie Fiennes, performance by Slavoj Zizek, 2012. that should afford us the opportunity to see things as they really are, to make transparent the manipulation of the advertising industry that consistently exploits and creates our desires and fears. The trouble of course is that the glasses that let us see the raw of everyday life, are designed and manufactured by Louis Vuitton.

Ideology critique is sanctioned and controlled by the machine of ideological reproduction.

Abloh pushes in the direction of producing a critical intervention that inevitably and clandestinely reinforces the dominant ideology. His denouncement of retail and commerce as unappealing is precisely an argument that appears to be against capitalist production and exchange, but still with an underlying and over-riding impulse to participate in a consumerist culture.

Abloh has deliberately designed each of his flagship stores differently, “never duplicating the same idea,”[34]Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Accessed December 8, 2019] because, “I don’t want stores…you should buy something if it speaks to you, otherwise you should go for the experience”.[35]Ibid.iv The constant bombardment of advertising has created a general resistance to being sold something, a sentiment Abloh has picked up on. This resistance coincidentally corresponds with the fact that there is nothing new to be sold in any case. In the “Experience Economy”, what one is sold as novel is the “vibe”, because there are no longer any new things, only old things remixed, sampled, rearranged, laid bare, off- set, and recontextualized in order to be presented as new—highly reliant on the “paradox as the driver of consumption”.[36]Nemesis, The Umami Theory of Value: Autopsy of the Experience Economy, March 2020 [Accessed 14 April 2020] Abloh describes the design of his Tokyo flagship as a space that,

is not even a store whatsoever, it’s an office called “Something & Associates”…post-it notes, water cooler, this, like, mid-century chair… what more does someone who’s travelling these generic cities want, like especially if you’re in Tokyo and your phone bill is too high and you’re like cruising on airplane mode, you just want WiFi…you wanna find where you’re going. That’s what the hierarchy of the space is gonna be, the retail is gonna be pushed away.[37]Ibid.v

The space is designed as a stage for office work, the quintessential image of mind- numbing alienated labour associated with the notion of the 9-to-5 unproductive administrative rank and file, complete with a ticker constantly running displaying the live Tokyo stock exchange. There is no overt injunction to consume (the experience is the product), but the ‘dead-end job’ mise-en-scène is incentive enough to resist (through consumption) the alienation that this space typifies.

As an immanent critique of the use and interaction of symbols and signs, Abloh’s making is also his undoing.

It is perhaps too cynical to note that Abloh’s rise to the top of the cultural space occurs through his construction of language; his invention and play of signs. Admittedly, this might be too literal a reading of both Abloh and Lacan, which is not to say they ought not to be read together. To repeat Lacan, “everything emerges from the structure of the signifier”.[38]Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. New York & London: W.W. Nor- ton & Company, 1981, 206. It is precisely the signifiers that produce the subject, and at once, eradicates the subject, they are the conditions that make critique possible, and once made, nullify it. For Lacan, there exists a dialectical relationship between the subject and signification. Given that signification lands in the field of the Other, in the symbolic order, the “signifier is that which represents a subject for another signifier”.[39]Ibid, 207. Abloh enters the symbolic order and is simultaneously neutralized by it. Again, repeating Lacan:

The signifier, producing itself in the field of the Other, makes manifest the subject of its signification. But it functions as a signifier only to reduce the subject in question to being no more than a signifier, to petrify the subject in the same movement in which it calls the subject to function, to speak, as subject.[40]Ibid.vi

The subject, for Lacan, is nothing if not alienated through language. Lacan’s exclusive vel seems appropriate here. There can be no meaning where there is being, and no being where there is meaning. The famous “your money or your life” scenario is meant to illustrate the operation of this or, whereby if you choose the wrong option, you lose both, but the other option yields only one deprived of the other. The same option is lost in either outcome. The problem of meaning and being is a non-choice for everyone—you come to language as an escape from the Real.

For the figure of the black subject, there is no option that yields at least one of the two options. All are already lost, always. Regardless of the altitude at the top of the culture industry, the pseudo-choice between meaning and being is already foreclosed for Abloh by virtue of his blackness. It is not that Abloh’s entrance into the symbolic order through his use of the signifier effectively cancels the possibility of being, in the way that the universal Lacanian subject might come to be. Abloh appears, but this apparition is the limit of his being in the world, of his making (in) the world. His deliberate employment of language is a desperate attempt at a choice, a desire for alienation and thus for subjecthood. The black subject must parody subjecthood of/in language in order to simulate the lack that constitutes the symbolic order. By instituting the lack, black “being” is presented as a perpetually unrealized potentiality, as if it were something that could have been grasped, as if the possibility of subjectivity existed at all. This effort mitigates the fact that the choice, however false, was never possible. If we accept the proposition that the black subject is the lack that props up the whole for white subjectivity, then the black object must invent a fiction of a lack (that is not also itself) in order to claim subjecthood. But there is nothing beneath blackness. Black is the nadir point. What monster must it imagine in order to be Subject?

Abloh’s commodities in the collection of “QUOTES” have replaced the label Off-White such that the signifier is the logo. The quotation mark becomes “a device that allows him to claim anything as his own—to put his name on it—in the most overt way possible”.[41]Michael Rock, “The Edge of Center.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 146. Whether the term Off-White appears on the garment, or whether the characteristic arrowed X emblematic of the brand is visible is less relevant than the appearance of these stylized signifiers. Having access to all the signifiers, any of them could suffice. One question we arrive at is to ask:

what becomes of language when every signifier is appropriated as a logo?

Under conditions of late capitalism all of language is placed between scare quotes, with the white market as the ultimate Master. Words “lose their performative power”,[42]Slavoj Zizek, ed. Mapping Ideology. London & New York: Verso, 2012, 18. insofar as they are made subject to the commodity relation. Abloh can successfully stick signifiers onto commodities. Perhaps, in another register, it is only within the commodity relation that some signifiers are sensible at all.

Language coheres only where the black person is property.

Christina Sharpe’s notion of dysgraphia[43]Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2016, 96. explains the impossibility of speaking of black people as human. It exposes the capacity for signification to hold – but only where the black is property, not person. For Sharpe, anagrammatical blackness— words and meanings that fail to take hold in and on black flesh—is the precondition for meaning making in general. The black “person-as-property” is the condition or background for when meaning is communicable/sensible and when it is not. It is not then that signification can never stick, it is more that it can never stick if the black flesh is to be considered person. Terms can be made sensible, but they are the terms reserved for things. Unsurprisingly so, given that the black person is the instantiating commodity, the original item whose trade is essential for the entire sphere of exchange. As property/commodity, meaning can be afforded, removed, altered according to consumptive patterns and the play of signification. This is precisely the prize of property. Abloh’s invention of signs remains in the realm of property, especially in the context of a cultural moment in which, “the values of the corporate are woven into the corporeal”.[44]Michael Rock, “The Edge of Center.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 143. The multi-hyphenate phenomena that is Virgil Abloh has not managed, despite every conceivable attempt, to escape objecthood. In the obvious sense this is by virtue of being black in the world, but less conspicuously because of what it means, in the most post-racial register, to be a “creative director”:

Creative directors not only guide the work that happens under their command, they also stand as an embodiment of the brand itself. In the most advanced cases, the brand is inseparable from the identity of the creative director…[45]Ibid.vii

For those who have the means to buy the work, and for those millions of youths following the idea, the fact of Abloh’s blackness and the controversy it ignites is built into the purchase. The attempt to rid oneself of objecthood has been collapsed again into something for sale. The consumer market, mostly white and now fashionably enlightened and liberal by decree, will consume whatever cutting edge design or process Abloh offers. The commodity is always fetishized. The complexity of Abloh’s life and work—that he belongs to no culture except the culture of consumerism, that his work is produced by the internet for the internet, that he was catapulted to the top of Louis Vuitton without attending fashion school, that he is black sans attitude—is all included in the price of any one garment or artwork. Creative directors “don’t deal in things, or not only in things, but in the stories that surround commodities that have become essential grease in the machinery of today’s social media-fueled form of commerce”.[46]Ibid, 142. Black creatives count as commodities, and their stories are currency—a core element in the white buying experience since modern slavery.

“Through what agency (volition? will?) does a Slave entify the signifier? Which is to ask, can there be such a thing as a narcissistic Slave?”[47]Frank Wilderson III, Red, White and Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2010, 77.

This article was first published in Propter Nos, Volume 4 Invention (Fall 2020), published by True Leap Press. Re-published in herri with kind permission of the author.

| 1. | ↑ | Taiye Selasi, “How to Be Both.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 131. |

| 2. | ↑ | Ibid.i |

| 3. | ↑ | Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, “Virgil Abloh: A Hundred Percent As Told to Anja Aronowsky Cronberg,” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica, 2019, 150. |

| 4. | ↑ | Ibid.ii |

| 5. | ↑ | Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Accessed December 8, 2019] |

| 6. | ↑ | Off-White is Abloh’s design house based out of Milan formed in 2013 |

| 7. | ↑ | Off white/ [Accessed December 10, 2019] |

| 8. | ↑ | Gabrielle Leung, Off-White & Musee du Louvre Collaborate on Leonardo da Vinci-Indebted Capsule Collection, 13 Dec, 2019. [Accessed December 30, 2019] |

| 9. | ↑ | Virgil Abloh opening set “BIRDS EYE VIEW” Tour, 2017 [2:25] |

| 10. | ↑ | Susanne Madsen, Virgil Abloh on Getting Political with Jenny Holzer, 16 June 2017 [Accessed December 11, 2019] |

| 11. | ↑ | Takashi Murakami, Virgil Abloh, 2018 [Accessed December 9, 2019] |

| 12. | ↑ | Mao Zedong, On Practice and Contradiction, London & New York: Verso, 2007, 74. |

| 13. | ↑ | Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject, London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2013, 24 |

| 14. | ↑ | Arthur Jafa & Greg Tate, Hammer Museum, 5 July 2017 [Accessed January 13, 2020] |

| 15. | ↑ | Virgil Abloh. “Theoretically Speaking” lecture, Rhode Island School of Design, 2 May 2017 [Accessed January 20, 2020] |

| 16. | ↑ | Michael Rock, “The Edge of Center.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 143. |

| 17. | ↑ | Ibid.iii |

| 18. | ↑ | Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Ac- cessed December 8, 2019] |

| 19. | ↑ | Alain Badiou, Theory of the Subject, London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2013, 24. |

| 20. | ↑ | Louis Althusser, For Marx. London and New York: Verso, 2005, 209. |

| 21. | ↑ | Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, “Virgil Abloh: A Hundred Percent As Told to Anja Aronowsky Cronberg,” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica, 2019, 149. |

| 22. | ↑ | Susanne Madsen, Virgil Abloh on Getting Political with Jenny Holzer, 16 June 2017 [Accessed December 11, 2019] |

| 23. | ↑ | Slavoj Zizek, ed. Mapping Ideology. London & New York: Verso, 2012. |

| 24. | ↑ | Arthur Jafa interviewed by Virgil Abloh in i-D, 16 September 2019 [Accessed December 10, 2019] |

| 25. | ↑ | Roland Barthes, The Fashion System. California: University of California Press, 1990, 6. |

| 26. | ↑ | In Barthes’ The Fashion System, he makes a distinction between the technological, iconic, and verbal structures of a garment. My concern here is with the technical insofar as it is also textual, rather than the written. |

| 27. | ↑ | Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Ac- cessed December 8, 2019] |

| 28. | ↑ | Alec Leach, Why Does Virgil Abloh Put Everything in “QUOTES”? 30 August 2017 [Accessed December 15, 2019] |

| 29. | ↑ | Ferdinand de Saussure, “Course in General Linguistics.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, edited by Vincent B. Leitch, New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2018, 836. |

| 30. | ↑ | Arthur Jafa interviewed by Virgil Abloh in i-D, 16 September 2019 [Accessed December 10, 2019] |

| 31. | ↑ | Ferdinand de Saussure, “Course in General Linguistics,” 831. |

| 32. | ↑ | Calvin Warren, “The Catastrophe: Black Feminist Poethics, (Anti)form, and Mathematical Nihilism,” Qui Parle, vol. 28, no. 2, December 2019, 363. |

| 33. | ↑ | Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. Directed by Sophie Fiennes, performance by Slavoj Zizek, 2012. |

| 34. | ↑ | Virgil Abloh, “Everything in Quotes” lecture, Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 6 Feb 2017 [Accessed December 8, 2019] |

| 35. | ↑ | Ibid.iv |

| 36. | ↑ | Nemesis, The Umami Theory of Value: Autopsy of the Experience Economy, March 2020 [Accessed 14 April 2020] |

| 37. | ↑ | Ibid.v |

| 38. | ↑ | Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. New York & London: W.W. Nor- ton & Company, 1981, 206. |

| 39. | ↑ | Ibid, 207. |

| 40. | ↑ | Ibid.vi |

| 41. | ↑ | Michael Rock, “The Edge of Center.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 146. |

| 42. | ↑ | Slavoj Zizek, ed. Mapping Ideology. London & New York: Verso, 2012, 18. |

| 43. | ↑ | Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2016, 96. |

| 44. | ↑ | Michael Rock, “The Edge of Center.” Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” edited by Michael Darling, Munich & London: DelMonica Books, 2019, 143. |

| 45. | ↑ | Ibid.vii |

| 46. | ↑ | Ibid, 142. |

| 47. | ↑ | Frank Wilderson III, Red, White and Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2010, 77. |