NIKLAS ZIMMER

Basil Breakey: Jazz contacts, Jazz culture.

cut paper itself.

Video collage of Basil Breakey photos titled “SOUTH AFRICAN JAZZ IN THE SIXTIES” edited by “FoRest”

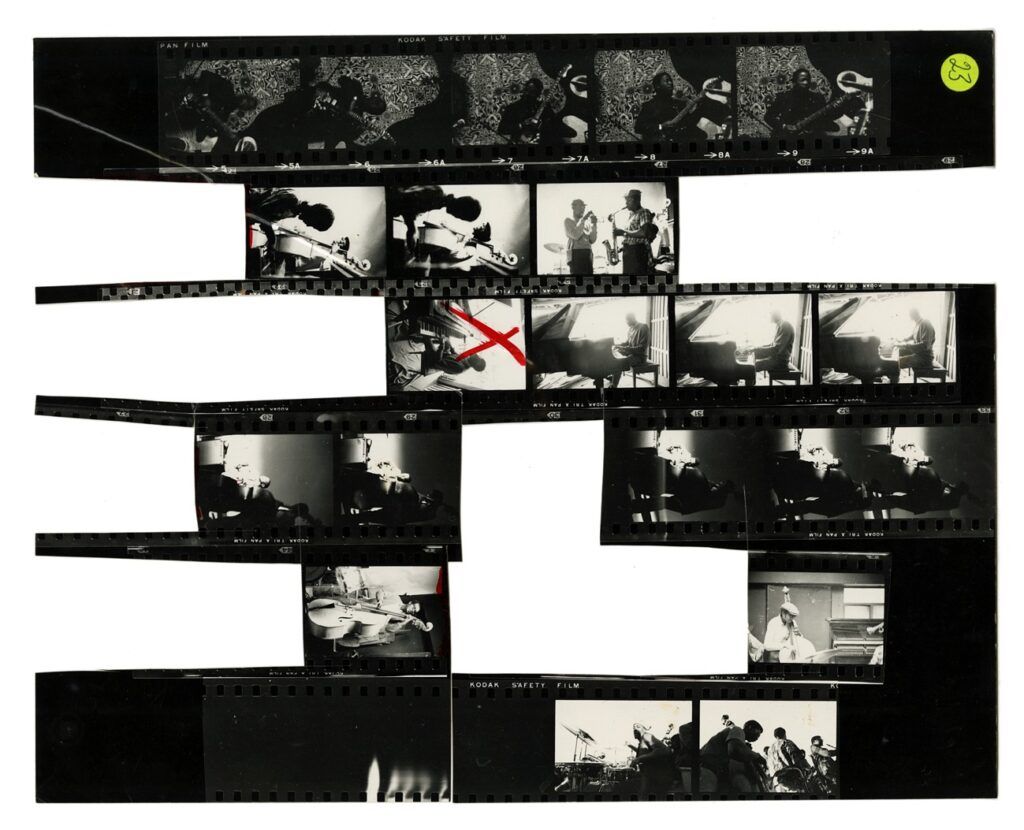

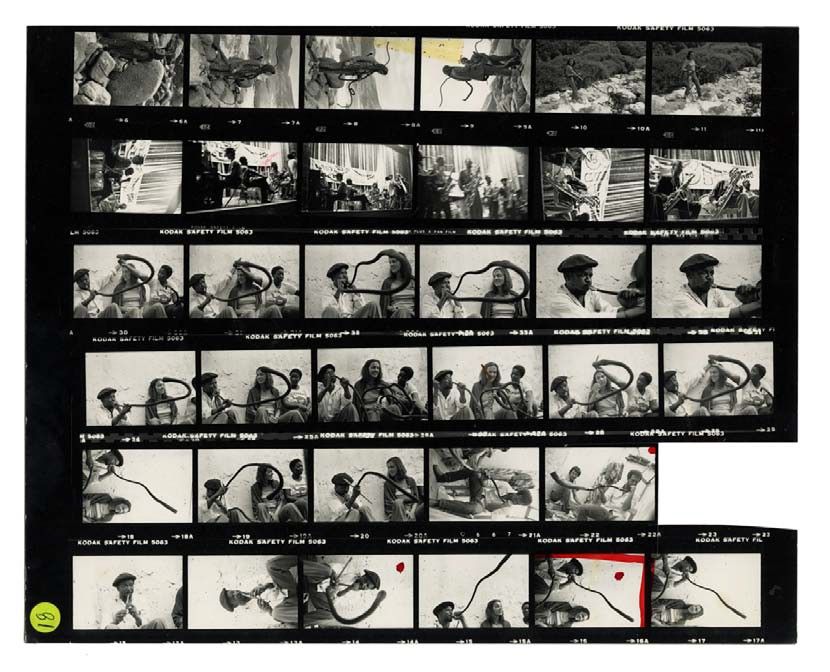

Figure 30. Approximation of a 1:1 scale view of Contactsheet24 printed at the proposed size (number 2), illustrating how photographs are never quite discreet from each other on the reproduction of the sheet: its surface quality is very pronounced reinforcing the coexistence of its constituent elements.

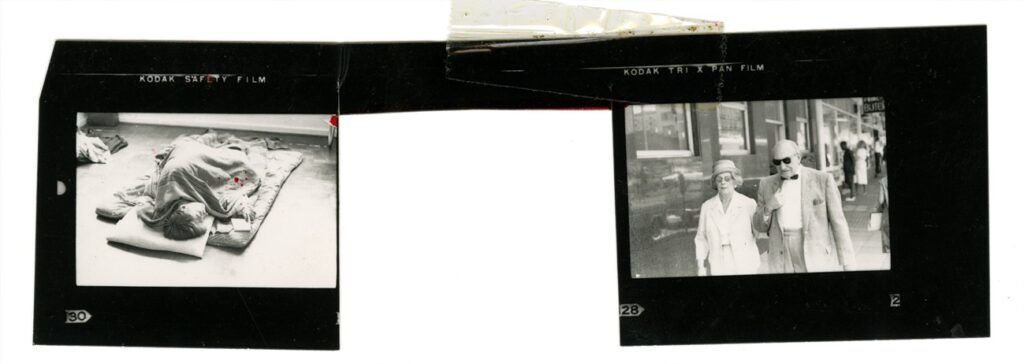

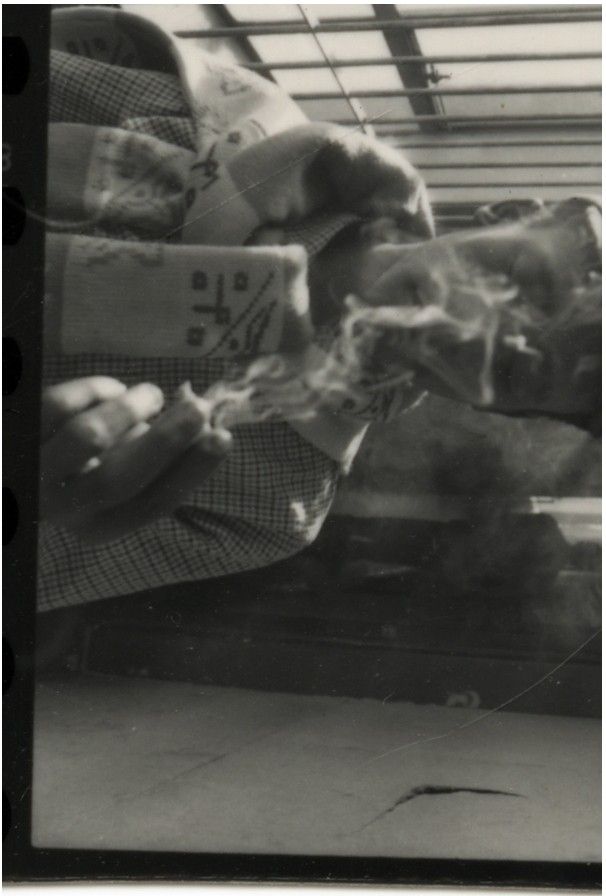

Figure 39. Fragment 04 (approximately 8cm x 3cm).

Basil Breakey: Jazz Contacts, Jazz Culture

Basil Breakey was born in Johannesburg on 3rd November 1938 and shortly thereafter moved with his parents to Port Elizabeth where he went to high school. As a teenager, he had a great admiration for Elvis Presley, even once attending a rock concert dressed up as the King of Rock. Jazz music did not play a role in his formative years. After school he began training as a bank clerk, but quite soon found himself transferred to Johannesburg due to his romantic relationship with the bank director’s daughter. Beyond this point, biographical information is scarce and contradictory.

From the interview I did with him only a few years before his passing,[1]Basil Breakey interviewed by Niklas Zimmer (Cat no. Avi6.06), 25.02.2011. Centre for Popular Memory Archive, UCT. I gleaned quite clearly that apart from not being able to recall certain things in his life, Breakey also did not wish to recall them – at least not for any official record. The more direct my questions were the more evasive his answers became. Breakey did pick up a camera around 1962 and started to learn the ropes of photojournalism in the darkrooms at DRUM. On the question of his chosen subject matter, ‘jazz’, he referred to an important conversation with his mentor and friend, the photographer John Brett-Cohen, who advised him to find and focus on his “own, special subject”. For a number of years, Breakey worked as a freelance photojournalist for a variety of newspapers, and then appears to have dropped out of any formal employment or paid work altogether, at least until the early 1970s, when he did some work for the Cape Times newspaper.

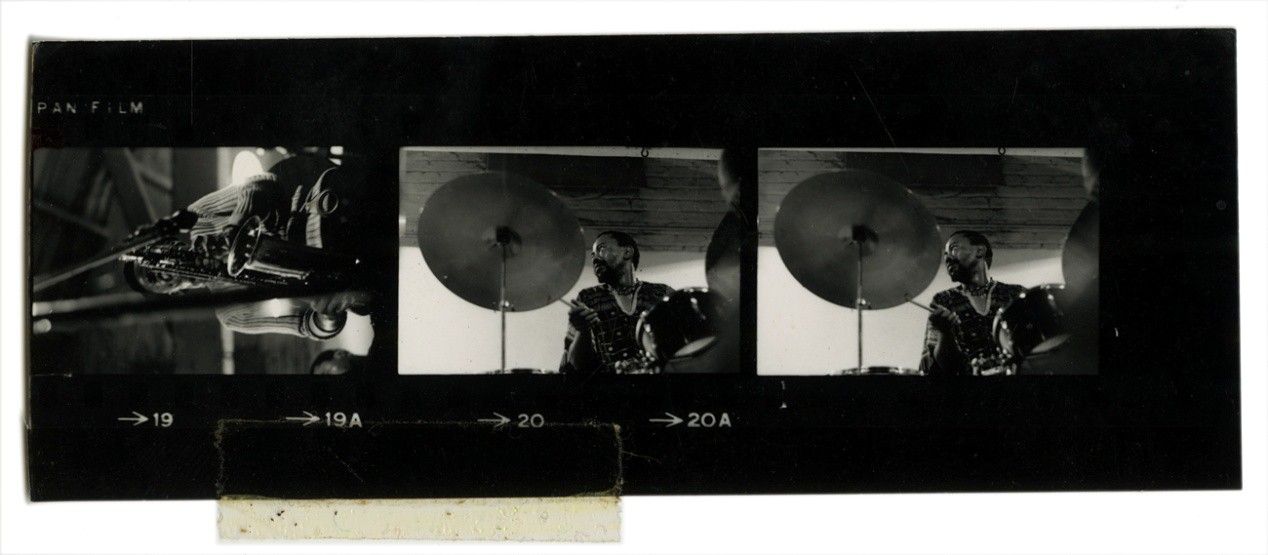

In the early 1960s Breakey met and made friends with a circle of jazz musicians whom he proceeded to photograph on a number of occasions, while they were performing or practising or just ‘hanging out’ together. Some of his stage rehearsal shots of the Castle Lager Big Band were used for a 1963 LP record, which is now one of the rarest collector’s items of South African jazz. The core group of this circle would soon, in 1964, go into exile as the Blue Notes – undoubtedly one of the most significant jazz combos in South Africa’s musical history. From that point onwards, Breakey had less to photograph, and only sporadically picked up the camera.

After a short period spent in Swaziland (1966–1968), Breakey moved to Cape Town, and started a family with a local woman, with whom he had four children. When I interviewed him in 2011, he remembered meeting his future wife at Greenmarket square, where she was selling tie-dye T-shirts, but he does not remember in which year. He also did not remember when or in what order his children were born, and when he got divorced. He would, often after a searching pause, answer most direct questions with, “You must ask Steve [Gordon] that.”[2] Basil Breakey interviewed by Niklas Zimmer (Cat no. Avi6.06); 25.02.2011. Centre for Popular Memory Archive, UCT. Steve Gordon was in written correspondence with them and acting as a kind of custodian or guardian, passing on to Basil the cash that they sent by post.

The ‘70s and ‘80s are only sketchily accounted for, but it seems that after years of intermittently finding shelter at friends’ homes, Breakey eventually ended up completely homeless. In the eighties, two retrospective exhibitions of his work were held, one in Cape Town (1988, The Jazz Den at The Bass), and one in Johannesburg (1989, Market Theatre). In this last decade of political struggle and the first decade of democracy, he found ad hoc employment and access to food and photographic materials through friends and benevolent colleagues, such as the well-known ‘struggle photographer’ and director of South African History Online (SAHO), Omar Badsha. In a conversation I had with him in June 2011, Badsha reminisced about the experience of employing Breakey as a darkroom assistant for about a year. Breakey proved not to be sustainably employable, because he would do unpredictable things, such as forgetting to close the front door of the house, which then lead to an opportunistic theft. Nevertheless, Badsha, like many others who know Breakey personally, speaks of him with a kind of forgiving fondness: “He was a hustler, but I was also a hustler, for years! In those days we would all help each other out. We would make soup, and whoever didn’t have food would come over to eat.”[3] Unrecorded conversation with Omar Badsha at his home in Woodstock, June 2011.

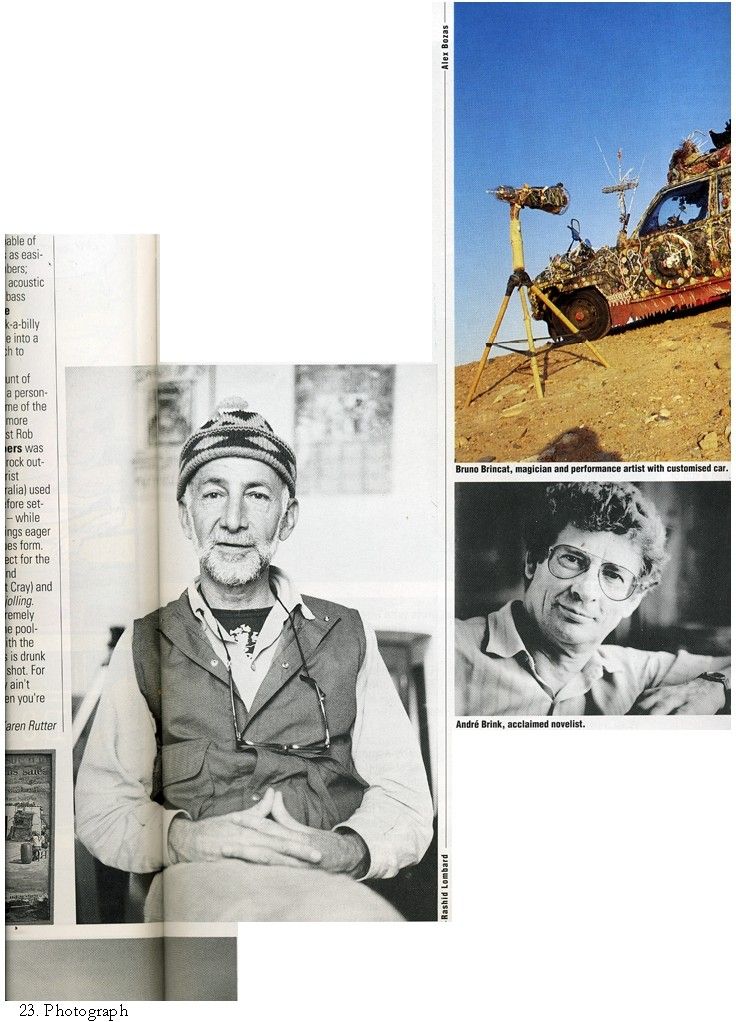

In a 1993 copy of ADA magazine, I found a short write up on Breakey, accompanied by a portrait photograph taken by Rashid Lombard, who would a few years later inaugurate the Cape Town International Jazz Festival, which he proceeded to direct for many years. In 1997, Beyond the Blues was finally published – four years after its announcement in ADA – and launched in conjunction with an exhibition at the Michaelis Gallery on Greenmarket Square, Cape Town.

In his last few years he was a softly spoken, gentle old man, spending his days at a local pub, without a home, and without clear memories of what would be cornerstone dates and events in the biographies of many. He could be spotted at local book launches, carefully paging through art books, which still held his interest. Sometimes, if he had been given some film and his old Pentax was not at the pawnshop, he would walk along the railway by the sea, snapping pictures of water-reflections, sea gulls or passers-by. These he sometimes had developed and printed on good grace in town. He always carried a few envelopes with these prints in plastic packets that contained his clothes and, if asked, would respectfully offer them for sale (ten Rand per signed Jumbo print). Among all these prints were always also some of his old jazz photographs. The estrangement felt at seeing a black and white print of a jazz saxophonist performing in the 1960s laid down by the photographer for a quick buck on a sticky, daylit bar counter in Kalk Bay in the 2010s is difficult to put into words.

Breakey’s jazz photographs

Basil Breakey produced some of the most directly aesthetic photographs that I know of a ‘lost’ generation of South Africa’s jazz. Beyond that, his photographs also present rare visual documents of live jazz in small venues in downtown Johannesburg in the early ‘60s, at a festival in Swaziland in the late ‘60s, and stadiums and small bars in Cape Town in the early ‘70s. He was one of very few photographers, sometimes the only one, present at these events. With the few frames he would shoot on such occasions he contributed not only to an historical record relevant to musicologists and a marginal public interested in local jazz legends, but also to the local, total archive of aesthetic and conceptual repertoires of the genre of jazz photography. Although jazz in South Africa was by then also no longer in its ‘roaring’ (1920s) or ‘golden’ (1950s) days as in the USA, it was also not yet indulging in a retrospective aesthetic, with a sentimentalist sound and ‘look,’ as was still to come with a rising commercialism.

I have considered the personal reasons for Breakey’s interrupted and discontinued oeuvre. While most of his individual photographs do not appear to necessitate a biographical reading, their particular constitution as an archival collection in fact does. Considering the very particular scene of which Breakey was part, and what the activities of that fringe stood for in the repressive socio-political context of South Africa, a close look at his images has the potential to stimulate a deeper understanding for the period he lived in. Breakey is one of the few visual chroniclers of this historical period who – however inadvertently, reluctantly or unsuccessfully so – engaged in documenting jazz culture “in that post-Sharpeville silence” (CTIJF workshop 2011), while many important players were going into exile.

From a contemporary perspective, it is interesting to note that at the time that Breakey was taking some of the images of jazz musicians rehearsing at Dorkay House in Johannesburg the now internationally-acclaimed, South African photographer David Goldblatt was also there, on his very first professional assignment, in September 1963. While photographing some of the same subjects in the same location at the same time, the young Goldblatt looked up to the young Breakey, not only because the latter had an insider status as an intimate friend of many musicians there, but also because “Basil had this unrestrained use of the camera, he was much less uptight than I was” (Goldblatt 2011).

Breakey’s photography tends rather to open up questions than provide a conclusive, historical narrative. In that sense, it is ‘unprofessional’. It is largely marked by gaps, absences and elisions. It runs out of time with its subjects – the Blue Notes go into exile, out of money – photography is expensive and Breakey was neither a wealthy enthusiast nor a full-time professional, out of motivation – Breakey makes jazz ‘his’ subject for about a decade, but later does not even go to listen to it much. Breakey’s work presents a relatively small collection of frames from that historical period and place: images that show how Breakey and his peers defied the massive socio-political complications at the fringe. ‘Representations of the past in jazz might benefit…by introducing the notion of a usable past or living history – a way of thinking about jazz performance that characterizes a new African diasporic sensibility in jazz performance’ (Muller 2006: 70).

The first, overall impression Breakey’s photographs leave on the viewer in relation to Breakey’s subjectivity is that of intimacy with his subjects. Despite his working with a reporter’s camera in the Bressonian tradition of capturing ‘decisive moments’, it is Breakey’s particular subjectivity that makes him as much part of his surviving photographic documents as whoever was in front of his lens at the time of exposure. Two aspects contribute to enabling in the viewer a sensation of bearing witness to a plausibly truthful record of a milieu, of personalities, of a life on and off stages. Firstly, there is Breakey’s ‘naïve’ honesty in relation to this very personal subjectivity, in which he was present while photographing. Secondly, there is a consistently non-invasive, essentially non-voyeuristic positioning of his point-of-view. Rather too incompletely encompassed in his own term ‘naïve’, this approach unselfconsciously subverts hackneyed notions put forward by other documentary photographers as a methodological programme: either enabling the subject to ignore the photographer (as if that were possible), or engaging the subject in the staging of ‘their’ (own) camera-image (again, highly unlikely).

In contrast to such complicated complicities, Breakey managed ‘artlessly’ to avoid two typical pitfalls of ‘people photography’: (1) de-personalisation and exploitation of the subject, and (2) the objectification of an observer-self (photographer and viewer alike) as voyeur. While every viewer is, in the strict linguistic sense, nothing but a ‘voyeur’, this term has developed to differentiate between two very different types of viewing: overt and covert, permitted and not permitted, harmless and harmful, acceptable and unacceptable, ‘normal’ and perverse.

Breakey operated with permission from his subjects. Had he chosen to fully exploit this situation, he may have produced fewer immediately ‘accessible’ images – in the conventions of photo-documentaries. This would have required a more self-consciously engaged, (self-) critical viewing. Therefore it is very difficult to resurrect his overall body of work as an oeuvre of artworks – incidental, naïve, brut, outsider or not. On the contrary, his continually obvious attempts at creating ‘jazz photographs’ in the particular iconic tradition of the modernist 1960s preclude such a reading.

Breakey’s work, neither ‘straight’ documentary, nor ‘high’ art photography, falls between the cracks of two possible modes of resurrection or reappraisal. Breakey cannot be rediscovered in the way in which, for instance, Billy Monk has been in recent years (e.g. by the Stevenson Gallery). Neither have the attempts been particularly successful to resurrect Breakey as an important contributor to the hidden history of South African jazz culture: Beyond the Blues has been out of print for a number of years, and, former chief curator at UCT’s Centre for Curating the Archive, Paul Weinberg’s exhibition Underexposed, of which a few of Breakey’s prints formed part, has not found any noteworthy public or critical resonance. In his 1997 review of Beyond the Blues, arts journalist Peter Honey writes:

‘…the whole is ultimately an incomplete and narrow portrayal. The photographer mostly fails to penetrate beyond the idealistic, clichéd depiction of jazz performers as doomed denizens of smoke filled, dingy session rooms and grimy passageways.’

According to such a logic Breakey was neither unselfconscious enough to take photographs without evidently worrying about their formal qualities as ‘Art,’ nor was he self-critical enough to develop his art/craft as far as it takes to receive noteworthy public or critical acclaim.

Breakey’s overall output appears at first quite homogenous, however small the variations in approach to and choice of subject matter appear to be. The fragments, re-envisaged as traces of unique instances of an engagement over time, become emblematic of an overall struggle, a motivational condition, on behalf of his black subjects. The visibility of the self and the definition of one’s identity through conflicting media, modalities and motivations has been the subject of much debate, specifically in post-colonial studies. It appears at first remarkable that Breakey, as a white South African during this particular period in South African history, engendered and maintained enough trust in his black musician ‘friends’ (as he always asserts) to allow him to photograph them repeatedly in a number of different contexts. Nevertheless, as one engages further with his archive, the question arises why Breakey did not manage to develop these relationships and situations into anything like a coherent reportage or narrative.

Breakey appears to have been continually aiming at getting individual, good performance shots – an approach that may lend itself to nothing less and, indeed, no more than a coffee table book on jazz in a very generic sense. Beyond that, the individual images do not enable the viewer to navigate through a significant, i.e. ‘telling’ narrative. At best, they allude to circumstances occurring beyond the frame. Breakey – trained (however cursorily) in the context of print media – must have understood well that to press the shutter release is only one of a plethora of decisions that a photographer makes in the development of a body of work. Yet his photographs present no more than glances and glimpses of scattered, ‘underground’ realities. They do not offer interconnected views, which would describe a context in full.

Again, it is worth pausing to consider that in the 1960s in South Africa, there were more limitations to be overcome for a jazz photographer than low lighting:

‘The unfettered power of the police in what was essentially a police state gave rise to a security culture where torture, bribery and intimidation were the order of the day. As a democrat or activist, you simply could not trust anybody, and in such a climate both journalism in general and documentary photography in particular came to be pursued essentially as guerrilla activities’ (O’Toole 2011).

This was a period marked by political oppression through a variety of terror mechanisms, such as, amongst many others, the system of ‘separate development’.

‘In 1955 [Sophiatown] was destroyed by the white racist government, an event that led to the radicalization of South African jazz music’ (Scaruffi 2002-3).

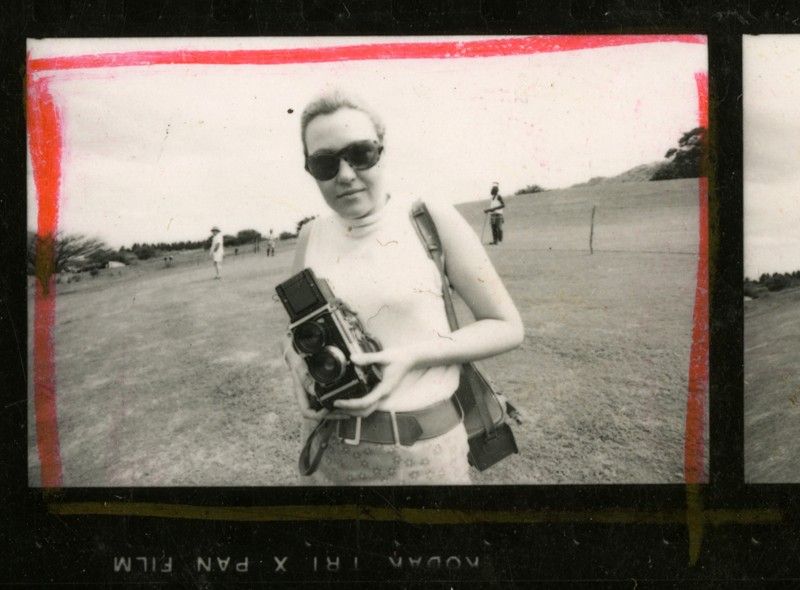

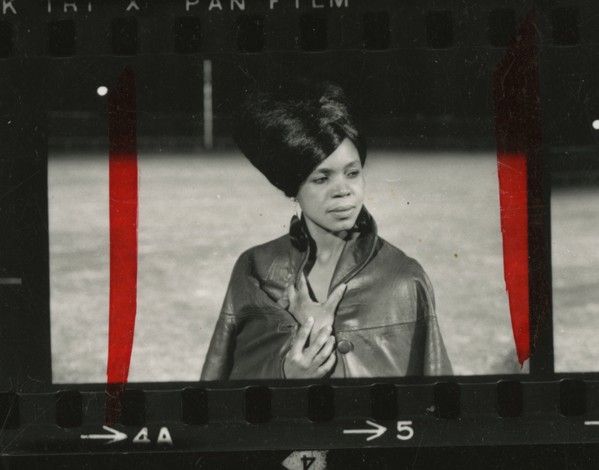

Particularly for artists and musicians, it was a time of extreme financial hardship – resulting in many Jazz musicians choosing to go into exile rather than to severely compromise, or altogether give up on, their careers. Breakey captured some of the hardships they underwent during this ‘jazz in exile’ period in photographs that clearly (and arguably self-consciously) break with the by then well-established visual idioms of the relatively young photographic genre of jazz photography. Breakey’s images show musicians resting on a mat on the floor of his flat, practising in the run-down rooms of Dorkay house, socialising backstage at miniscule, short-lived venues, or playing on stage to small or non-existent audiences. They appear as figures drifting through an entirely insular world.

Figure 45. Fragment 04 (approximately 8cm x 3cm).

While they do project a sense of ‘cool’ in their dress and demeanour – for instance Dudu Pukwana choosing to wear big sunglasses at night – Breakey’s images of them are close-up, direct and alive with empathy. What comes across is that they are isolated, downbeat, up against an environment far too hostile for making it through, even somehow. This impression is reinforced by contrasting nuances with how some of his compatriots lived and saw things:

‘We have all these great documentary photographers, but we don’t have a culture of photography. What we do captures history. Music played an important role in the struggle. When we were banned during the state of emergency, how did we get things going? We had a jol, we had a gumba – that was our rally’ (Lombard 2011).

In essence, one could say that Breakey’s photographs are both anti-typological and anti-topographical: they resist offering up general meanings. Much like their subjects, in their living and dying, in their ebbing and flowing into and out of the archive, they embody resistance and reluctance, defiance and denial. The fact that most of the musicians Breakey photographed passed away relatively young, and that Breakey himself had hardly any memory left towards the end of his life, underscores this.

Beyond the Blues

The book Beyond the Blues can be viewed as an attempt to present Breakey’s photographs stably as iconic or classic[4]In common usage, the terms ‘iconic’ and ‘classic’ are used synonymously to describe photographs that depict or themselves come to embody a symbolic significance – a representation of something of great significance to larger groups of people: subcultures, nations, even mankind. ‘Jazz Photos’, in direct relationship to the aesthetic forms, traditionalist formalities and technical formalisms involved in the practices of an identifiable, universal genre of ‘Jazz Photography.’ While the history of Jazz is always, in the first instance, an American story of socio-political resistance and liberation on behalf of repressed and dispossessed African-Americans, the history of jazz photography tends to be less discontinuous, less visibly contentious. Most jazz photography has, perhaps inadvertently, been at some point or other co-opted into the marketing schemes of the music industry, feeding into public and popular perceptions and prejudices around what ‘jazz’ was, is, and should be. For many musicians, the idea of a ‘golden age’ of jazz (1959 being its official, final peak) to be continued indefinitely by faithful classicists of the genre is seen as a shamelessly manipulative marketing ploy by the music industry. The contemporary ‘post-jazz’ trumpeter Nicholas Payton puts it this way:

‘Jazz is a marketing ploy that serves an elite few. The elite make all the money while they tell the true artists it’s cool to be broke’ (Payton 2011).

The title of Breakey’s book, taken from a poster fragment visible in the background of one of the photographs[5]Beyond the Blues pg. 15 (as Basil wistfully pointed out during our interview), becomes ever more strangely ambiguous when one peruses the book. While the title would seem to suggest a cathartic overcoming of sorts, a rising from the ashes and a hopeful horizon of change, something quite easily contextualised by the date of publication, 1997, the ‘rainbow nation’ years, the pictures themselves certainly do not carry any such message – neither individually, nor in their arrangement over three biographically chronological chapters (Pretoria, Swaziland, Cape Town). In a brief online text on this history aimed at directing the reader towards Beyond the Blues, Steve Gordon writes:

‘As Breakey explains, there was not yet an audience for the music. The guys were struggling, and recognition was only to come later – first abroad, and later still, in South Africa. Breakey therefore, was not a photographer on a brief to cover a “happening” jazz scene, bounded by the constraints of news deadlines or the directive of picture editors. He documented a world which he shared, and which he captured in what he describes as an “almost naive” style. (Gordon 2003).

Breakey, who never wrote a single by-line, referred to his approach as ‘naïve’. This might have been a personal response he developed in relation to general formal and technical questions directed at him as somebody without any formal (academic) training in the visual arts. He may have more-or-less actively incorporated such formal and technical naïveté in his personal modus operandi, or quite simply have adopted the label in quasi ‘self defense’ against the kind of interrogation that photographers are often faced with.

Steve Gordon’s archive

At the time of this research being done (2010-2012), Basil Breakey’s photographs resided in a small house in Carstens street, Cape Town – Steve Gordon’s office at Musicpics cc. Steve Gordon (born 1961), a writer, sound engineer, road manager and photographer of South African popular music with a degree in social anthropology from UCT was acting as the custodian of Breakey’s practical and financial affairs. Gordon, initially approached by the publisher David Philip to write the commentary for Beyond the Blues as a writer and researcher, moved on from there into the role of archivist: he now not only held Breakey’s negatives, saleable hand prints and ephemerae, but also his financial and personal records, and kept up correspondence around legal and financial matters with Breakey’s family.

Practically, the ‘archive’ consists of a standard office folder with all of Breakey’s negatives[6]This batch of loosely accessioned negative strips may be approximated to have come from about one hundred rolls of film – a less-than-average amount of material even for a hobby photographer, let alone photo enthusiast from this time., the scans thereof stored on a computer hard drive in the same office, and a box of ephemera: invitation cards and letters, the mock-up of the book Gordon and Breakey produced and published with David Philips, and a small number of contact sheets in a large old envelope. There are also a few hand printed enlargements (signed, but not editioned) in a folder by the shelf.

The old envelope, in particular, presents visual and textual fragments that do not stick together as coherently as the texts and contexts around the lives of the photographs mentioned above. The contact sheets inside it are not ordered or accessioned in any way. According to Steve Gordon, they are leftovers from an unspecified, but reportedly drawn-out, period of successive attempts by Breakey to order, select and present his work to potential publishers, editors and buyers. Most retired or deceased professional photographers from the pre-digital age typically leave behind tens or even hundreds of thousands of negatives (depending on their respective specialisations) and hundreds or even thousands of contact sheets (this even more relative to their particular way of working).

In stark contrast to such archival excess, Breakey’s leftover objects communicate a sense of fracture and confusion and, in so doing, they seem to express the snapping and hacking away that is both at the heart of the universal business of professional photography, but also the heart of the contemporary, post-colonial South African business of cultural reappraisal, reconstitution and indeed reconstruction, at times characterised as a ‘heritage craze.’[7]Notes from Professor Daniel Herwitz’ presentation at Archives and Public Culture conference March 2011. History is written, rewritten and unwritten by interested parties. For many photographers and musicians who were active during South Africa’s 1960s, it appears that the historical present is marked by “a deep sense that it didn’t happen for the guys, whatever the dream was. All we have is history, but no future” (Gordon 2011).

Gordon called Musicpics cc an ‘archive,’ but it is worth noting that, as a private business defined by an interest in generating revenue for Breakey through the licensing of image rights, it could perhaps have been more appropriately termed an agency. It also did not strictly meet any international standards for photographic archives in terms of accessioning, preservation or access, nor did it include in its mission to address any programmatic concerns around visuality in archives or the role of archives in contemporary society. Archival images can become iconicised by historical developments, if they are accessible to the public. Effectively, it would seem that Musicpics cc did not attempt to engage with ‘the question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow’ (Derrida 1996: 12). Rather, it seems that Gordon was following the root conception of ‘archive’ as relating to ruling and governance in a gate-keeping role. Put differently, if archival objects are sequestered or obscured with interest, they are being handled as capital, which ‘can be generally defined as assets invested with the expectation that their value will increase’ (Matich 2007).

A subjectivity for Breakey

In any local jazz environment there are active ‘jazz personalities’ who are not musicians themselves. Most audience members on any given night may just be fans of the music, but some regulars take what they experience in response to the music into their life and work[8]Michael Titlestad (2004) has theorised on the creative and journalistic writing that happened in response to jazz in the apartheid era., and vice versa. They may be historians, journalists, artists – or photographers.

Basil Breakey was one of those jazz personalities: a regular and an insider. Everyone I interviewed confirmed that Breakey was indeed friends with the musicians he photographed, a fact which was verified by Louis Moholo-Moholo, the drummer and last surviving member of the ‘Blue Notes’ in my interview with him. Moholo-Moholo spoke of Breakey as being “very quiet, very cool… you see in those days it was hip to be quiet” (Moholo-Moholo 2011). The nature of Breakey’s friendships, however, is left unclear in such an account, and even more so in the photographs. Nothing can enable us to fully grasp what the exchange, the air, the language, the gesture was like in retrospect. Breakey’s photographs allow glimpses, invite empathetic guesswork: his subjects appear to be aware of him, but tolerantly, comfortably so. In fact, they often appear quite disengaged. This could be owing to Breakey having asked them to pretend he wasn’t there – a common directive, given by many photographers – but it could also indicate more generally that his presence was quiet; maybe he simply didn’t ask for much.

Many music or events photographers are attracted by proximity to fame and glamour. Being part of a presently famous in-group, a fashionable, hip collection of brilliant individuals is something exhilarating – it can feel like being part of history being made. In the segregated world of 1960s South Africa, jazz history was indeed being made by these young stars in front of Breakey’s lens, shining brightly in the hidden-away havens of smaller, more illicit venues and private functions. There is a phenomenon of ‘deferred genius’ at work, an at times symbiotic, at times parasitic relationship between photographer and musician. The photographer may believe that by participating in the musician’s lifestyle, they also become a bit of a genius. In the terminology of professional journalism, often in relation to war photography, this is called ‘getting too close’. Famously in music reportage, it happened to American celebrity photographer Annie Leibovitz on tour with the Rolling Stones in 1975:

‘I did everything you’re supposed to do when you go on tour with the Rolling Stones. It was the first time in my life that something took me over… Mick and Keith had tremendous power both on and offstage. They would walk into a room like young gods. I found that my proximity to them lent me power also. A new kind of status. It didn’t have anything to do with my work. It was power by association’ (Leibovitz 2008).

What remains of Breakey’s photography are almost exclusively ‘work’ images, which leaves the viewer in a paradoxical position as to how to assess them, what weight to assign to them. With regard to their near-exclusivity vis-à-vis their subject matter, they speak of passionate, focussed dedication, yet with regard to their small number, they speak of a haphazard, unfocussed lack of commitment towards just that subject matter. Every family album engages the imagination, even in the case of its absence. It seems that in Breakey’s life, taking jazz photographs took precedence over, or stood in for, taking conventional family photographs. The question arises as to whose family album this is? It is not that of Breakey’s (bloodline) family, but rather that of his brotherhood.

Rather than construing a grand ‘Family of Man’[9]Edward Steichen’s monumental ‘Family of Man’ exhibition opened at MoMA in New York in 1955, and – while never out of print as a book and universally hailed as one of the most important collections of photographs of the century – has also been criticised for its generalising claims of universality, and abrogation of responsibilities inherent in the gathering and exhibiting of images of deep inequalities in the world under the given title. narrative, Breakey’s pictures inhabit the homes of those immediately, that is familiarly, connected with those depicted. Envisaging their process work, the contact sheets, on the walls of the cities that are home to those who come after does not construe ‘us’ as one metaphorical family unit in the sense of an integer community of like-minded or similarly interested individuals in a nation, a societal stratum or the like. On the contrary, it visualises the work of construction that is the self of infinite observers. It is rather an imagined album, an imaginary home in the mind of those who attain their sense of citizenship to a particular home-place and mother-tongue through looking at a wider frame; an album that allows breaches and discontinuities, contradictions, pauses and silences to become visible and, metaphorically, at least in relation to jazz, audible.

This does not necessarily point to a professionally contained subjectivity as chronicler. By contrast, there are many examples of more stably inscribed ‘chroniclers’ of jazz culture in present day South Africa. They are easily found, too – just follow the hashtags on social media.

Yet, even if they might have been out photographing jazz for many nights for years, actively sharing their images together on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, a website, etc, they may well choose to avoid placing themselves on a shared historical trajectory with “the likes of” Breakey.

While every process of representation is en-cultured and, therefore, historically bound up in contingencies and contestations, some of the more ‘artless’ or ‘naïve’ representations appear to create a more interpretative, ruminative space than others. The latter typically adhere more clearly to a brief, and are thus professionally successful in terms of communicating a clear, specific message. Perhaps such ‘on task’ and advertorial photography is what becomes embalmed in the historical embrace of a particular ‘cultural’ discourse[10]See for instance: Clifford, J. & Marcus, G. E. (Eds.). 1986. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (A School of American Research Advanced Seminar). City: University of California Press. while, conversely the less easily co-opted, ‘free’ photography of someone like Breakey then lies in wait in the archive to complicate, even contradict contemporary prejudices of a given period of history.

Jazz in South Africa

‘Jazz,’ it must be noted, is a contentious term. It can be used in a derogatory sense, invoking associations with shebeens[11]Once illegal drinking houses, almost exclusively located in townships. and noise and, of course, blackness in a time where that denoted inferiority towards whiteness. To say ‘South African jazz’ in that sense not only means to invoke an inherent racism, but also other problematic connotations: such a term potentially denies the originality, indigeneity and unique cultural heritage of the South African music that is herewith being associated under one, foreign umbrella term. It can be seen to suggest a lack of originality, since jazz, as is often generally assumed, is American music and any other nationality that plays jazz is thereby building on the foundations of American culture. I wish to clearly distance myself from such views. Without any value judgments attached, it can be said that the history of South African jazz is marked by adaptations and (re-)appropriations. Michael Nixon clarifies this here:

It is from the ranks of the dance ensembles that the jazz musicians emerged. As young people they revolted against the music they were required to play in the dance bands, which they came to perceive as old-fashioned and even crude. They were interested in playing American music’ (Nixon 1995: 19).

Adaptation means change, emancipation, affirmation of new structures and societies.[12] see for instance: Kuper, L. & Duster, T. 2005. Race, class, & power: ideology and revolutionary change in plural societies. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. This adaptation is structured around the unique local, historical context. As we are merely dealing with an African-American re-import of those musical figures which once forcibly left African shores on slave ships, the changes endured during the century-long exile become relevant for its perceived originality.

Considering the rich intertext, the socio-political conditions of non-American Jazz culture, past and present, desire and require a different reading. The wealth of parallels between the politically charged histories of Jazz in the USA and in South Africa tempts reductionist comparisons: the self-conscious referencing of the respective other – Americans searching for their roots in African cultures, Africans searching for a contemporary identity in American culture – goes back at least as far as the 1920s. Peretti writes:

‘Since the 1920s, fans, critics, and other members of the self-styled jazz community have promoted the music as America’s home grown art form’ (Peretti 2001: 588).

Furthermore, Coplan stresses how local Jazz styles did by no means develop merely in slavish imitation of North-American influences:

‘Since the urbanization of African music in the late 1920s… black South African jazz musicians have identified with the international popular musical community, often performing entirely within the black American musical idiom for fully urbanised, Western-educated concert audiences. The same musicians, however, could readily adapt American arrangements to indigenous rhythms, phrase structure and harmony, thus creating unique forms of African jazz including marabi in the 1920S and 30s, tsaba- tsaba in the 1940S and kwela and mbaganga in the 1950S and 60s. They did so primarily for working-class Africans who sought to express an urban self-identification and to achieve urban status through music that reworked American materials within the familiar, culturally resonant framework of African principles of composition and performance’ (1982: 114)

Importantly, what emerges here in terms of a discussion of ‘culture’ beyond ‘music’ is that the lines of connection between the politically charged race-histories of jazz in the USA and in South Africa constitute a new discursive formation. Titlestadt has written extensively on this, as the following section encapsulates well:

‘Jazz discourse travelled across the Atlantic and provided a repertoire for the improvisation of urban black culture in South African townships. Through constructing relational pathways of meaning (often by weaving together the narrative ‘‘licks’’ of African American jazz narrative and the contingencies of apartheid experience), South Africans assembled identities that, in certain respects at least, eluded both the definitions and the panoptical technologies of the apartheid ideologues… jazz was, in a variety of ways, a subversive alternative to the machinery of the apartheid state, a notion commonly expressed in terms of its carnivalesque or ludic musical production in the face of colonial oppression’ (Titlestad 2008: 211- 212).

Locally, jazz is a cultural practice through which at least four generations of South Africans have reflected on and also fought for their place here and in the world. It is an American echo to the African colonial Diaspora – all the aspects beyond its multitudes of musical permutations – dress, dance, language, life style, and so on – is about re-shaping identity, anti-authoritarianism, individual and collective creativity, and a certain bitter-sweet joie de vivre, the indomitability of the individual human spirit in the face of oppression and hardship. The parallels between American and South African Jazz culture are abundant and striking, but at times also misleading. The photographers of the 20th centuries on both sides of the Atlantic captured stories of segregation and identity politics. In a widely quoted article from 1966, jazz journalist Lewis Nkosi writes:

‘Jazz is a music which has its roots in a life of insecurity, in which a single moment of self-realisation, of love, light and movement, is extraordinarily more important than a whole lifetime. From a situation in which violence is endemic, where a man escapes a police bullet only to be cut down by a knife-happy African thug, has come an ebullient sound more intuitive than any outside the US of what jazz is supposed to celebrate – the moment of love, lust, bravery, incense, fruition, and all those vivid dancing good times of the body when the now is maybe all there is’ (Nkosi 1966: 34).

Various studies have traced the arrival of jazz and its precursors in South Africa, the politics of their adoption, particularly by urbanized black communities, and the emergence of a rich hybrid performance tradition (see, among others, Ballantine 1993, 1999; Coplan 1985; and Erlmann 1991). What has remained largely unexamined, though, is the textual scaffolding of these musical transactions. Not only did jazz itself journey across the Atlantic (embodied by performers, printed on scores, and impressed on records played on imported gramophones) but it also arrived embedded in a discourse of identity, history, and politics. Mahlaba informs us that:

‘Musicians living in coastal towns were the first to have contact with visiting black American sailors who played jazz or sold them jazz records. These towns were therefore a hub of inspiration for the resident jazz communities’ (Mahlaba 2008: 18)

Jazz culture in South African cities began to comprise stages, birthplaces and melting pots for – at least temporary – de-separation and un-division of citizens across the colour bar. From the 1950s onwards, some jazz clubs began to present ‘grey areas, not so dominated by coloured culture’ (Nixon 1995: 23). Mason, in writing about a key figure in this context, Vincent Kolbe, describes:

‘During the 1950s and into the ’60s, [Vincent Kolbe] was a vital part of Cape Town’s multi-racial jazz scene, which flourished brightly and briefly, bringing together musicians and fans who happily ignored South Africa’s culture of segregation and white supremacy’ (Mason 2010).

Various indigenous musical forms, some of which were themselves imported not too long ago historically, mixed with American idioms, themselves evolving, never far away from or free of political life. Online, in Roddy Bray’s Guide to Cape Town, we read:

‘During the 1950s and ’60s two traditions of jazz developed from the popular dance-bands of Cape Town. One was influenced by American musical styles; others practised what was to become known as ‘Cape Jazz’. The latter maintained that local jazz should be based in working class dance music, whether it was ‘African’ marabi and kwela, or it was ‘coloured’ vastrap and klopse’ (ANON 2008).

A turnaround time was of course the 1960s. Pianist and composer Merton Barrow remembers in an interview with Colin Miller:

“…in that period, that very bad period. I think when I really had an opportunity of listening to Winston play saxophone from deep inside of him. And he would play to the limits of his abilities to… it was an enormous experience just to listen to him play. To experience the pain he was obviously feeling that time because there was very little freedom that time. And it must have affected a lot of people around about that time. Certainly with their music. I’m talking about people that improvised, that were able to speak with their music” (Barrow 1998).

Jazz culture has a particular sociological makeup, which has been of great significance in the underground, resistance and other ‘alternative’ movements in South Africa throughout the Apartheid years. Perhaps as its highest achievement, Jazz music provides an artistic medium for the musicians and their audiences with which to build their identities – give thoughts to their minds, feelings to their hearts and dance to their bodies. Furthermore, the venues in which this culture thrived – often in the side-alleys, on the outskirts, the docks, the ‘locations’ – offered release and escape from the oppressive abnormality of daily life in those times. These were places where races did actually mix (a bit), where difference and togetherness could be celebrated rather than having to be fought for. While Jazz culture has always been about black resistance and identity, it has also always been open to cultural confluences far richer than stereotypical black/white or east/west dichotomies. In South Africa, as in black America, popular music, of which Jazz is the most complex, has provided an incommensurable field of expression for the values and meanings on which new community structures are based.

The audiences for live performances of South African jazz music are as heterogeneous as its broad range of stylistic influences and, therefore, highly representative of the demographic realities independent of Apartheid ideology: many so-called ‘African’ (or ‘black’) players and members of audience, some so-called ‘coloured’ players and members of audience, and a few so- called ‘white’ players and members of audience. Variations obviously depended on the location of the venue, but as long as one is looking at audiences listening to what can still within reason be called ‘jazz music’[13]As opposed to more specifically ‘black’, ‘coloured’ or ‘white’ popular musics with their more exclusively grouped audiences, for instance (in that order again): Marabi, Klopse and Boeremusiek., this melange remains stubbornly ever-present across the historical periods and urban spaces of South Africa. Nixon describes this in the following:

‘In the clubs there was mixing to the point of contravening the Immorality Act! Not only was mixed clubbing a problem for the apartheid government, but individuals’ relationships were targeted for legal harassment… Had it been left to itself, the jazz scene could have developed into something remarkable… It was an apartheid casualty’ (Nixon 1995: 23).

The fact that the early 1960s are the beginning of a drawn-out period of cultural stagnation and decline in South African cultural life has been the topic of many investigations, academic and popular. The post-Sharpeville (1960), pre-Soweto Uprising (1976) ‘emptiness’ can be read as the dark backdrop to the elegiac work of visual artists, poets, dramatists and musicians of that time. It remains difficult to appropriately trace all of this work historically, not only because it has not yet been exhaustively researched and documented, but because so much of it was never locally exhibited, published or performed (let alone recorded), and literally never became part of popular memory. Jazz culture, however, has always provided a sense of possibility and agency in this regard. Peretti clarifies this in reference to an emerging culture of popular memory work:

‘Well before the 1960s, jazz interviewers held a populist and racially progressive desire to “let the musicians tell their own stories.” Like oral historians, jazz interviewers sought to question aging subjects while they were still able to share their memories’ (Peretti 2001: 590).

Many texts in the arts and humanities tend to either focus on the pre-1960s or the post-1976 periods, although in the years 1960 – 1976 twenty thousand activists were arrested[14]For these statistical figures, see:[last accessed: 2011/06/02], political parties were banned and resisters began to form armed units. Nkosi sets this scene as follows:

‘[T]he attitude of the South African government has been stiffening toward racially mixed audiences and bands. This hostility toward jazz should surprise no one conversant with the history of the music since jazz has always been the music of the outlaw, the anarchic and the subversive. Since the early fifties jazz in South Africa has been threatening to burst the very seams of apartheid. In the affluent white Johannesburg suburbs of Park Town and Houghton daughters of wealthy Jewish families hosted African musicians, often providing a relaxed friendly atmosphere in which integrated groups could ‘jam’ together. In this milieu of social ambiguity and underground revolt even interracial love affairs were not unheard of despite the fact that under strict South Africa’s sex laws stiff penalties are laid down against all black and white shenanigans’ (Nkosi 1966).

Contextualising ‘Jazz photography’ as a genre

‘Happily jazz exists. Everyone hates ‘jazz’ but it’s the only word to describe a musician who wants to say something fresh and react to what others are doing around him’ (Bruford 2011).

The oldest, most extensive and well-developed archives of Jazz photography in the world today exist in the USA. They aid not only in documenting the history of a vast musical evolution, but also that of urban (sub-)cultures, who share a set of characteristics that seem closely linked to what jazz music means and aids for its performers and audiences: a deep desire for gaining freedom from oppressive rule, and for expressing one’s individual voice in the context of a meaningful community of human beings. South Africa does not have such institutions. Instead, there is a rather barren landscape of scattered, only partly institutionalised silos of jazz-related materials, of which photographs form the smallest quantity. For a variety of reasons, there is a firmly entrenched gate-keeping mentality in place, particularly around photographs. There is no doubt that ‘jazz photographs’ hold great potential for sparking socio-historical discovery and debate, but to find them in this landscape is currently very difficult. A character in Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet speaks of the acute rarity of those positioned to renegotiate images in context:

‘The only people who see the whole picture,’ he murmured, ‘are the ones who step out of the frame’ (Rushdie 2000: 146).

General observations have already been made on the uses of ‘documentary’ and ‘art’ photography as established genres, however inherently contested. I have done this to highlight the importance of asking contextual questions over and above technical questions about photographic production. With this in mind, the most relevant aspects of ‘jazz photography’ towards a definition of it as a hybrid of several sub-genres from within the separate categories ‘documentary’ and ‘art’ respectively are elaborated. I will ask firstly who produces photographs of jazz or ‘jazz photographs’ and for what purpose and then secondly, how and where these images are encountered, experienced and in fact used by others.

First of all it is worth mentioning that strangely enough there is no dictionary or encyclopaedia definition of ‘jazz photography,’ in spite of innumerable publications and exhibitions of jazz photographs to date, and even more, the worldwide mass of photographers known as ‘jazz photographers’ who mention ‘jazz photography’ as one of their main subjects. This already indicates that photographs of jazz emanate from several different contexts, where they are created with very different motivations and projected usages in mind. Deduced from this, four different types of photographer make images of jazz appear:

Firstly, there is the photojournalist, commissioned to take either editorial pictures of jazz musicians or of jazz related news, mostly events. Depending on their brief, the publication for which they are working and his personal background, this type of photographer will aim to do their job well by illustrating or augmenting the written feature or news story with a visual account of a concert or a good personality portrait. They are generally quite unconscious of any conceptual tradition of picturing jazz. Usually, they have one or two pictures to file for printing, and perhaps ten to twenty for the database. Then they move on to their next assignment: a car crash, a robbery or a court case. This does not make them a ‘jazz photographer’, nor what they do ‘jazz photography.’ Typically, their photographs of jazz events or musicians disappear in the newspaper’s ‘archive’, which in South Africa is more often than not a storeroom full of unaccessioned prints and negatives, or a badly managed filing system.[15] I speak not only from the perspective of a disgruntled researcher, but also from a month of experience working as an intern/freelancer at a well-known newspaper in Cape Town. These isolated images might regain relevance years later: not for their possible visual qualities, but due to factors outside of them: they happen to depict Mrs X, who has now died, and a writer needs images of her for a monograph.

Secondly, there is the commercial photographer, who makes most of their income in the advertising industry, but typically takes on editorial work as well. Nowadays, professionals from the music industry (musicians, record producers, events managers) will commission them to create a range of different types of promotional images for them (online portfolios, CD covers, posters). These images are generally classified into different categories (portrait, action shot, abstract) before being tagged with the keyword ‘jazz.’ Importantly, the specific brief for the photographer will ask for a particular ‘jazz look’. This is the moment at which ‘jazz photography’ as a primary category emerges. The jazz aesthetic is largely constituted by a set of visual references from post-war American popular culture, roughly up until the late 1960s. Important here is that the contemporary commercial photographer will be given ‘tear sheets’ or other references in order to recreate that recognisable look from elements of a bygone popular visual culture. In other words: they are briefed to work within the genre of jazz photography. The term ‘jazz,’ conjures up a fairly defined visual style. Even contemporary stylistic influences for layout, graphic design and typography in the case of jazz are executed in an aesthetic convention that is well over half a century old. The conditions for the production of jazz photographs in the first half of the last century were so totally different from now, that it is surprising that the style or ‘look’ of jazz photographs has not changed much since. The music industry was less professionalized, and many of the now ‘classic’ jazz photographs were created without a brief. Lastly, it is important to mention that due to the fact that commercial photographs are treated and paid like marketed goods, they are however distributed, stored and retrieved very differently from newspaper photographs. They become more visible through a number of different channels, they last longer in the public imagination – contributing to defining the public image of a band, musician, location or even a city.

Thirdly, there is the professional photographer working ‘on their own steam’: shooting jazz would not be their bread-and-butter. In fact, it is usually costing them to take these pictures, but they do it anyway. This type of photographer is present in the scene – in journo-speak ‘embedded’ – for the sake of their own enjoyment and their own project, however consciously they may be driving it. They might be hanging out with the musicians before and after the concert, taking pictures according to their own agenda, typically with a social documentary aspect to it. Perhaps they are also just snapping pictures for the sake of remembering. This visual chronicler typically loves jazz music, or is fascinated by an aspect of jazz culture, and is usually quite conscious of the visual history of the jazz aesthetic. Their independent project may be in view of an exhibition of fine art prints, a book publication, or simply to expand his portfolio. The project is typically conceived of as a visual document of times and places, significant events and people gathering there, around jazz music. They want more than one picture in a newspaper, or five to ten in a magazine. They want to tell a more personal story perhaps, to grow a new branch to a known aesthetic, to be as free as possible to be expressive with their photography. Beyond all this, such projects are also always driven by a personal, philosophical engagement with the temporal paradox of photography: a look through the viewfinder becomes a look into the past, and last night’s shots already contribute to the conceptual archive, and may in fact one day become publicly accessible within an actual archival collection, perhaps even a curated retrospective. The American jazz photographer Herman Leonard, who made a huge contribution to the photographic ‘look’ of jazz, points out the conditions enabling his approach:

‘You can’t do today what I did then. You can go to a studio, you can go to a club, you can go to a concert, but what do you end up with? A guy standing in front of a microphone with a spotlight, and no matter what kind of photographer you are, you’re going to get the same shot…You see, the things I got were shot in little clubs with great audiences, with moody atmosphere, or in recording sessions with everybody together being inspired…That to me is the tragedy of the electronic age: You lose that cohesiveness, you lose that inspiration’ (ya Salaam & Leonard 1995: 2).

Last in the list of types of photographers who take jazz-related pictures is the amateur, who is motivated mainly by the desire to record a pleasurable or significant moment. They normally are not aiming to sell or ‘do anything’ with the photographs they take. They take snaps to remember a special occasion, driven by their own personal interest. The prints or digital files rarely go beyond the confines of the proverbial suitcase under the bed, or their personal social media page. At most, they are a photo-enthusiast, in which case their jazz photographs may find discussion at a camera club, or be posted on a jazz- or photography-related discussion forum online. Incidentally, their photographs float deliberately on the traditional aesthetic platform of old classics. In their sort of visual “Karaoke” typically their pictures stick out by the absence of innovative, explorative realisation. The amateur’s personal collection of photographs of jazz culture may indeed much later become published or exhibited if incidentally they constitute the only record of a specific event. However, due to the fact that the images may in fact not be very well crafted and that their primary motivation did not engage aesthetic considerations, this is quite rare. The amateur’s photographs rarely achieve more – and often in fact less – than a deictic account of who was where when – the ‘how’ and ‘why’ are typically well beyond this.

None of the typologies presented above are complete, exclusive or exhaustive. They rather serve as generalised subject-positions from which to work further. Basil Breakey, for instance, falls quite squarely between the classic jazz photographer and the amateur. He produced very few other photographs than those negatives which are now in the Musicpics cc archive and most of which we can see spread across the contact sheets. On this basis, he cannot be considered to have been a full-time, working professional. Corroborating this is that he gave up freelancing for newspapers after two or three years, and Juergen Schadeberg’s Tropix photo agency, for which he worked afterwards, was itself ‘short-lived’ (Department of Arts, Culture and Heritage 2011). Indeed, how Breakey sustained himself I could never fully ascertain.

Breakey had a good technical foundation, and an awareness and admiration of other photographers’ work. He had his own SLR camera, and access to film stock and a darkroom. He was also good friends with the musicians he photographed, and met them wherever possible to photograph them performing, rehearsing and relaxing – something that was not easy in the racially segregated apartheid period. Beyond that, many of his photographs have a playfulness that suggests an amateurish desire to just take ‘family’ snaps, without further ambitions, just for memory’s sake. This in-between-ness of Breakey’s oeuvre makes it at once confounding and compelling. His body of work resists classification, since the individual photographs range from technically accomplished, yet artlessly banal ‘snaps’ to highly expressive photographs, which communicate an intense engagement with their subject. Breakey documented musicians whom he admired and took snapshots of them as his friends. This is the mix of photographic genres and types of photographer in Breakey’s images and subject-position: for himself, he recorded the musicians as his friends, and to his audience he presented them as noteworthy professional artists: in short, his images were produced, in both senses of the term, between the roles of amateur and aesthetic chronicler respectively.

The kind of photography that warrants distinction within/as a discrete category called ‘jazz photography’ is an aesthetically self-reflexive social documentary photography with jazz culture as its central subject. As an exclusive professional pursuit it is exceedingly rare, since it bears a number of risks and obstacles: firstly, because there is little money to be earned with it and, secondly, because it almost inevitably involves contestations around ethics and rights (who is imaging whom, and in what capacity?), relevance (why should we care to look?) and platform (where and how do we get to see the work?). Its production requires visual and musical fringes to meet as a sufficiently connected and unified social fringe in rehearsal rooms and jazz bars. In effect, jazz photographers – as visually artful social documenters – share many life skills and aesthetic approaches with the jazz musicians they are photographing: survival skills, shrewdness, and the ability to adapt to different contexts on the one hand and, on the other, a well-trained, creative alertness to shared moments, where listening and seeing become active response-abilities of one’s’ trade. In jazz photography, the relationship between the two kinds of artist – photographer and musician – ideally transcends the distanced sensationalism of hard news journalism, the superficial artifice of commercial photography, and the artless subjectivity of amateurism. The relationship is, at least symbolically, an equal one. In this moment, jazz photography can become a genre of its own: where art is created and amalgamated with the other art, music.

‘At our best and most fortunate we make pictures because of what stands in front of the camera, to honour what is greater and more interesting than we are. We never accomplish this perfectly, though in return we are given something perfect – a sense of inclusion. Our subject thus redefines us, and is part of the biography by which we want to be known’ (Adams 1996: 179).

The term ‘Jazz Photography’, as any other photographic genre (for example: ‘Landscape Photography’, or: ‘Still Life Photography’), conjures up a few prominent figures that have contributed to its standard feature set. For two main reasons, these are predominantly from the USA: firstly, jazz is originally a US-American art form, and secondly, after its internationalisation, it has continued to be popularised as an American thing. Therefore, the first ‘Jazz Photographers’ from before World War II are Americans, simply due to the fact that they were present at the time, making this aspect of their indigenous culture one of their subjects. The next generation of – now more professionalised – ‘Jazz photographers’ are also American, due to the fact that they were commissioned to contribute visually to the international popularisation of Jazz, emanating from the USA outwards via the mass media.

In an essay examining Roy DeCarava’s collection of jazz photographs The Sound I Saw – improvisation on a jazz theme, Richard Ings explores the complicated relationships that link African-American visual art to the practices, patterns, and aesthetics of jazz and blues music and claims that DeCarava’s images ‘add a new dimension to the intertextuality of art and music…[they] not only focus attention on a different visual medium, but also reveal how African-American music and visual art alike emerged from a complex social world where different forms of dance, display, style, and speech served as sites of struggle and self-affirmation, as repositories of collective memory, and as ways of calling communities into being through performance’ (2010: 20).

Over the course of the 1950s, jazz culture in the broader, commercial sense, became internationalised, and began to merge with other indigenous popular cultures all over the world, which profoundly affected its visual representation. While Jazz was now being performed outside the USA by non-Americans to non-American audiences in a large variety of cultural contexts, the very notion of it as something specifically recognisable, unified (and unifying) began to change. Its ‘golden age’ was over, and ‘Jazz’, theoretically and ideally at least, became whatever musicians and listeners would make of it. This is in line with other aesthetic developments in modernism. It is important, however, to keep in mind that there is a crucial difference in reception between a local, live audience, and the ‘market’ that buys commercially available recording-products, such as online mp3s and CDs in stores, or ‘requires’ certain types of (jazz) music to be played on radio.

Similarly, the role played by the necessarily different aesthetic intentionalities in creating ‘jazz’ for a local (live) listenership, or an international one (via publications of recordings) cannot be underestimated. Clearly, Jazz music and the image of Jazz, are subject to an immense amount of re-interpretations and re-presentations once all those records have been shipped and flown out into the world from the United States. It is notable, however, how stable this quintessentially hybrid musical complex of forms has remained. It can be observed in countless instances to the present day, how conservative – perhaps ‘conservationist’ would be the better term here – musicians and audiences have remained with regard to certain stylistic characteristics of ‘Jazz’ – its music as well as its visuality. Melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, an ‘authenticity’ of tone, sound, phrasing … can all be used to refer to music as well as to images.

Some of the American photographers that essentially created the genre of ‘Jazz Photography’ are Herman Leonard, Rico D’Rozaro, Roy DeCarava and William Ellis, as well as all those that photographed for the Blue Note record covers: Francis Wolff, Bill Hughes, Buck Hoeffler, Charles Keddie, Herb Snitzer and Reid Miles. The photographic ‘look’ of Jazz was imported to South Africa by sailors[16]see: ANON. 2004. South African Jazz: Political History. All About Jazz. [Online]. Available: [last accessed: 01/12/2010]. in the form of record disc covers (labels such as Blue Note, Impulse!, Verve, Prestige and others), dedicated Jazz magazines (Down Beat, Metronome), as well as lifestyle and news magazines (Life, Time). Alan outlines the formalisation of this image-culture in the following breakdown:

‘In the early years the choices were three – a formal band pose, a formal portrait, or the “jazzed-up” picture in which the musicians are stiffly posed in attitudes of not-so-wild abandon with half the band sitting on the piano. Somehow, it took the photographer a long, long time to understand what jazz is, and it was not really until the early 1940s that there began to be caught something of that relaxed, disordered, and very special world of the jazz musician. The “artistic” side of jazz photography did not appear until after World War II, and it has only been in the past few years indeed that a jazz photographer has tried to indicate moods or thoughts or concepts in a picture.’ (Alan 1956: 429).

Presently, we witness the look rather than the approach mentioned here, being perpetually recreated by the music industry as broadly accessible, i.e. literally ‘smooth’ or ‘classic’ ‘Jazz’ commodities. A visual exemplification of this locally is the self-published Cape Town International Jazz Festival 1998-2008 coffee-table book, a volume entirely devoid of accompanying text, as if the images could speak for themselves. In this context, the medium is the media, reifying nothing more than itself/themselves. The musicians are turned into beautiful/exotic props, engulfed by swathes of artificial lighting, staged between a large, paying crowd on the one side and the large banner-logos of the sponsors on the other. This popular image of jazz was not always as stably registered in genre conventions as it now appears. Some of its forms were through-and-through avant-garde, and barely survived even on the fringes of urban cultures. Those artists actively involved in the classical modernist peak of 1960s jazz culture are now either dead or very old. In South Africa, one of the last living photographers from that time was Basil Breakey.

In relation to music, there is an inherent tragedy in the documenter’s progress through life and work. Similarly to the sound engineer and other non-musician, music-industry workers, the documentary photographer or music journalist has to, in order to do their work properly, ‘get close’. They have to love what they do from the outset, otherwise the hardships on the long and arduous way to making a meagre living out of what they do would evidently not feel worth it. The photographer has to really love his subject. This is where the tragedy comes in: their subject does not love them. Musicians conventionally, eventually grow to distrust most who work for the music industry, who might potentially want some of their hard-earned money. Historically, countless jazz musicians have played night after night for little to no money, while the takings at the bar go to the owners of the establishment, while a hired sound person is paid their full price (and a hired photographer theirs), while the photojournalist might take some ugly shots, and write badly about the show. That is to say: the rare bird of a photographer who works for the musicians is often busy working through some of their own motivational psychology: a deep admiration for and attraction to the musicians. Through capturing and re-presenting something of the spirit animating the musicians, the photographer vicariously lives that spirit for a moment. It can be a quasi-ritualistic (and of course deeply neurotic) practice of adulation and theft.

Jazz photography, as we have seen, operates at the limits: the limits of socio-political hardship, of available light, of mental and emotional states. It also operates at the conceptual limits of the medium of photography itself. There is a creative dynamic at work in taking photographs of things that are particularly difficult to photograph well, which seems to hold the much-mentioned futility of the photographic endeavour somewhat at bay. To actually succeed in taking a reasonably sharp picture of moving musicians in extreme low-light conditions, such as a badly/dramatically lit, crowded stage in a venue or rehearsal space at night is a skilful achievement in itself. To commit to doing it without money and in a repressive political environment takes dedication and belief. To commit to sustain jazz photography as a personal project takes a certain kind of stubbornness around what photographs can be expected to do. David Goldblatt made this point in our interview when we were talking about Dorkay House:

“You know, the problem with music from the point of view of photography is that while you’re there, and the beat is there, it’s enormously exciting and inspiring but when you look at it cold afterwards, there’s no music… and the beat is gone. And whether you’re dealing with a philharmonic orchestra or a jazz musician it’s the same. So the photograph has to carry some kind of weight or spirit or resonance that… can’t any longer be felt in the ears. And then – this is, if you like, the problem for the photography of music or a musician – and, I mean I’ve experienced that many times, I’ve been present in Dorkay House, I heard Kippie talking to his instrument on the stage and it was inspiring. But afterwards, it was just cold. I don’t know how you can transcend some of the basic facts of what’s in the photographs. I don’t know”. (Goldblatt 2011).

Goldblatt, a professional art photographer, had for the previous five decades developed a particular positionality towards the South African people (buildings and landscapes) which he documented within the framework of a large number of ambitious and methodical projects. Breakey by comparison did no such thing, which marks by contrast the purpose of my review of his archival material: his in-between position as both-and-neither amateur n/or professional photographer has left us with intriguing and informative object-surfaces that are open to multiple readings. There remains much mystery and pleasure in pouring over the surfaces and depths, the details and textures, the embalmed moments unfolding, the still sound shimmering up at us in the contact sheet fragments left behind by Basil Breakey.

This text is an edited version of chapter three of my Master’s thesis: Zimmer, N. (2012). Jazz contacts : envisaging Basil Breakey’s photographic remains beyond the archive. (Thesis). University of Cape Town, Faculty of Humanities, Michaelis School of Fine Art. Retrieved from.

| 1. | ↑ | Basil Breakey interviewed by Niklas Zimmer (Cat no. Avi6.06), 25.02.2011. Centre for Popular Memory Archive, UCT. |

| 2. | ↑ | Basil Breakey interviewed by Niklas Zimmer (Cat no. Avi6.06); 25.02.2011. Centre for Popular Memory Archive, UCT. |

| 3. | ↑ | Unrecorded conversation with Omar Badsha at his home in Woodstock, June 2011. |

| 4. | ↑ | In common usage, the terms ‘iconic’ and ‘classic’ are used synonymously to describe photographs that depict or themselves come to embody a symbolic significance – a representation of something of great significance to larger groups of people: subcultures, nations, even mankind. |

| 5. | ↑ | Beyond the Blues pg. 15 |

| 6. | ↑ | This batch of loosely accessioned negative strips may be approximated to have come from about one hundred rolls of film – a less-than-average amount of material even for a hobby photographer, let alone photo enthusiast from this time. |

| 7. | ↑ | Notes from Professor Daniel Herwitz’ presentation at Archives and Public Culture conference March 2011. |

| 8. | ↑ | Michael Titlestad (2004) has theorised on the creative and journalistic writing that happened in response to jazz in the apartheid era. |

| 9. | ↑ | Edward Steichen’s monumental ‘Family of Man’ exhibition opened at MoMA in New York in 1955, and – while never out of print as a book and universally hailed as one of the most important collections of photographs of the century – has also been criticised for its generalising claims of universality, and abrogation of responsibilities inherent in the gathering and exhibiting of images of deep inequalities in the world under the given title. |

| 10. | ↑ | See for instance: Clifford, J. & Marcus, G. E. (Eds.). 1986. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (A School of American Research Advanced Seminar). City: University of California Press. |

| 11. | ↑ | Once illegal drinking houses, almost exclusively located in townships. |

| 12. | ↑ | see for instance: Kuper, L. & Duster, T. 2005. Race, class, & power: ideology and revolutionary change in plural societies. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. |

| 13. | ↑ | As opposed to more specifically ‘black’, ‘coloured’ or ‘white’ popular musics with their more exclusively grouped audiences, for instance (in that order again): Marabi, Klopse and Boeremusiek. |

| 14. | ↑ | For these statistical figures, see:[last accessed: 2011/06/02] |

| 15. | ↑ | I speak not only from the perspective of a disgruntled researcher, but also from a month of experience working as an intern/freelancer at a well-known newspaper in Cape Town. |

| 16. | ↑ | see: ANON. 2004. South African Jazz: Political History. All About Jazz. [Online]. Available: [last accessed: 01/12/2010]. |