In February 2013 my research assistant, Ms. Handri Walters stumbled across a cardboard box buried in a cupboard at Stellenbosch University’s Sasol Museum. The box contained a skull and two instruments for classifying eye and hair colour. The skull was originally from the university’s Anatomy Department. The hair colour chart was in a shiny, silver container with the name Professor Dr. Eugen Fischer engraved on it. I was stunned by the timing of this find. Only two days earlier, while going through the Eugen Fischer collection at the Max Planck Society Archives in the Free University campus in Dahlem-Berlin, I had stumbled across an identical instrument with twenty gradations of hair colour from blonde to black. I had also come across hundreds of photographs that Fischer had taken of mixed race Rehoboth Basters in 1908 in German South West Africa. These photographs were typical anthropometric photographs consisting of frontal and profile portraits taken for racial classification purposes.

Before I left for Berlin I had asked Handri Walters to look around the campus for eye and hair colour charts that the anthropologist Professor Robert Gordon had recalled seeing when he studied at Stellenbosch University in the late 1960s. Finding these objects at the Sasol Museum raised a number of questions for me and my anthropology colleagues at Stellenbosch University: what was the prevailing scientific paradigm that required the use of such classifying objects, what scientific objectives did Eugen Fischer have in mind with his Rehoboth study and, finally, how did these objects end up in the Arts and Social Sciences Faculty at Stellenbosch University?

We realised that such questions had important implications for understanding the wider history of the human sciences at the University of Stellenbosch. In particular, we decided that it would be important to investigate whether the legacies of racial science and scientific racism had been adequately addressed given the current imperatives of transformation. So where would we begin in order to understand the significance of finding Fischer’s imprint at Stellenbosch University and why is this important? Let me begin with a brief history of Fischer.

In 1908 Fischer began his study of Rehoboth Basters. Fischer, an anatomist and physical anthropologist who had studied medicine at the University of Freiburg, focused his study on 310 Rehoboth Basters of mixed Boer, German and “Coloured” ancestry. He used genealogical sources, photographs, eye and hair colour charts, and head and body measurements to investigate whether the “interbreeding” of peoples of different races would result in a new type of mixed race.

Fischer also wanted to know which racial characteristics were dominant and whether, and how, new environments affected emigrant races. Finally, he was interested in whether the fertility of mixed race people (Mischinlinge) was impaired. Fischer’s findings, which were published in 1913 in a book entitled The Bastards of Rehoboth and the Problem of Miscegenation in Man, concluded with wide ranging recommendations for colonial policy.

Fischer viewed the Rehoboth Basters as useful intermediaries for the purposes of German colonialism and suggested that they could become the low level officials and policeman. Based on his findings he also called for a strict prohibition on mixed marriages in the colonies. It was this recommendation that was later to influence Nazi policies to promote “the protection of German blood and honour.” This was done through the 1935 Blood Protection Law that prohibited marriage as well as non-marital relationships between Jews, and other people of “alien blood,” and Aryan Germans. This Nazi Marriage Act of 1935, which drew on the 1927 “Immorality Act” of the South African Union, came to be known as the Nuremburg Laws.

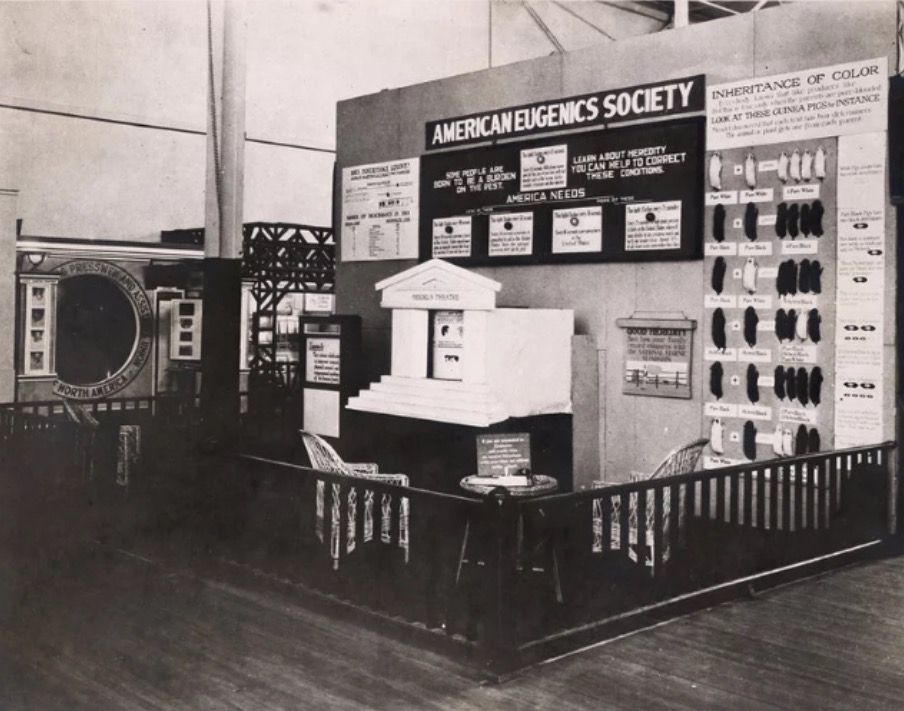

Fischer’s Rehoboth findings on what he claimed were the dangers of ‘racial mixing’ were also later used to justify classifying and targeting “foreign races” – Roma, Sinti and Jews – in Nazi Germany. While doing research for my 2016 book Letters of Stone: From Nazi Germany to South Africa,[1] Steven Robins, Letters of Stone: From Nazi Germany to South Africa (Cape Town: Penguin Random House Publishers South Africa 2016) I discovered that the hundred racial laws that had slowly and systematically stripped-down Jews like my father’s family in Berlin of their property, professions, livelihoods, citizenship, freedom of movement, and dignity in the 1930s, had their roots in Eugen Fischer’s racial science developed in German South West Africa two decades earlier. Fischer’s eugenics was also part of an international eugenics movement that successfully lobbied for the 1924 Immigration Restriction Act in the United States, making it virtually impossible for German Jews to flee to the United States. Similarly, my father was not able to rescue his family trapped in Berlin due to the eugenics-inspired 1937 Aliens Act that effectively shut South Africa’s doors to Jewish immigration.

All of this was done in the name of the new international science of eugenics and claims of evidence that the heredity of human racial characteristics could be explained through Mendelian rules of genetics. These scientists claimed to have solid scientific evidence that recessive genes of racially mixed populations ultimately contributed to physiological, psychological and intellectual degeneration. It was this frighteningly inhumane version of racial science that was later to find its ultimate expression in the Final Solution.

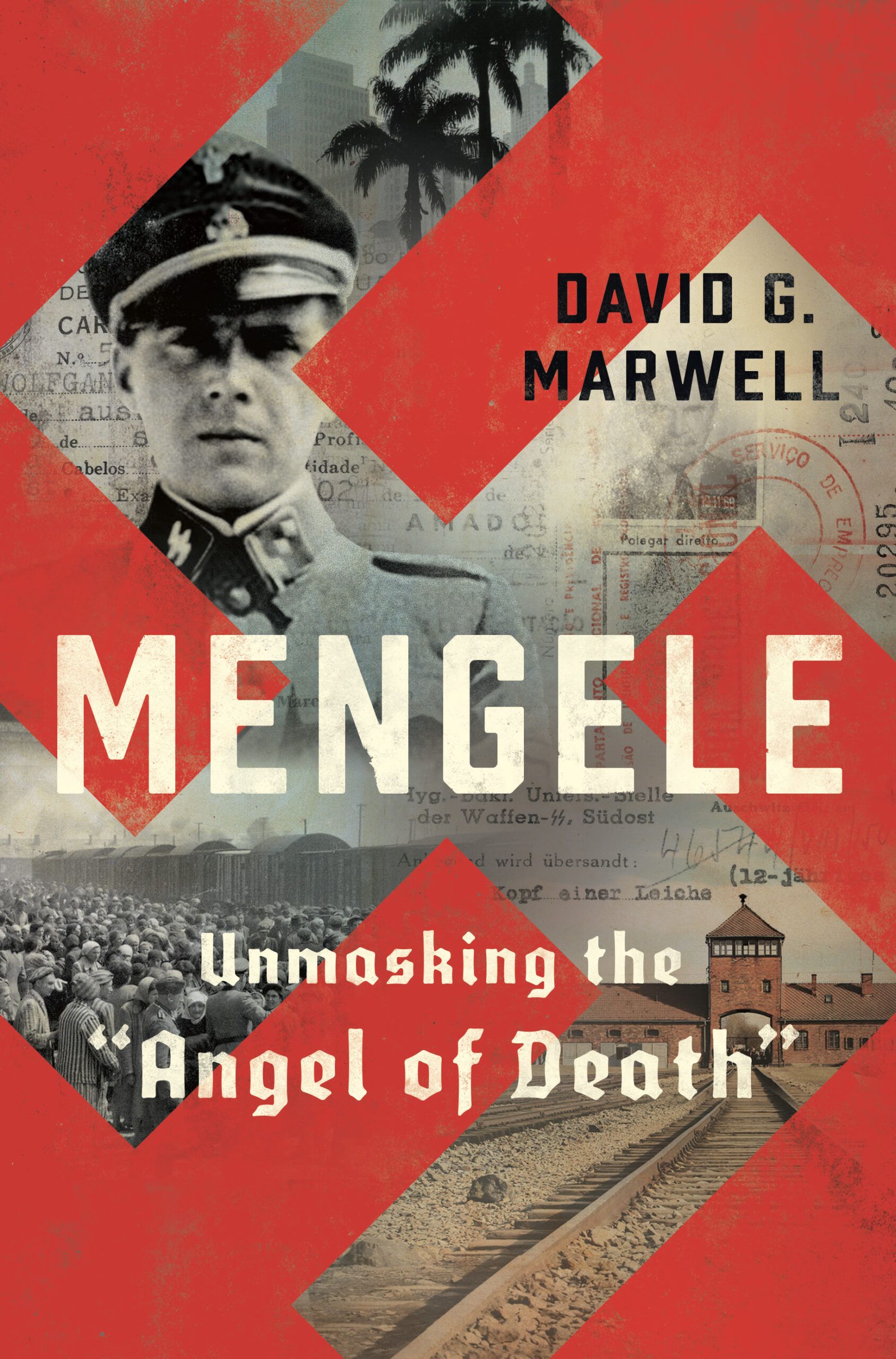

The Rehoboth study launched Fischer’s successful scientific career in Germany. Even Hitler read his work when he was in prison in Munich in 1923 and he cited him favourably in Mein Kampf. By the late-1920s, Fischer had become a leading figure in an international racial hygiene and eugenics movement. From 1927 to 1942 he was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics (KWI-A) in Berlin. From 1933 onwards, Fischer’s Institute became increasingly involved in Nazi policies ranging from euthanasia, to the racial classification of Jews and Roma and Sinti (Gypsies), to enforced sterilization of the mixed race “Rhineland Bastards,”[2]Rhineland Bastard (German: Rheinlandbastard) was a derogatory and racist term used in Nazi Germany to describe Afro-Germans, believed fathered by French Army personnel of African descent who were stationed in the Rhineland during its occupation by France after World War I. There is evidence that other Afro-Germans, born from unions between German men and African women in former German colonies in Africa, were also referred to as Rheinlandbastarde. and medical experiments with concentration camp inmates. By the time the Second World War began, Dr. Joseph Mengele was sending Fischer’s Institute blood samples and eye specimens of Roma victims of Auschwitz’s gas chambers.

Fischer was an ambitious man who believed that scientific expertise should dictate state policies. After struggling to influence policy during the democratic Weimar Republic era, the rise to power of the Nazis provided him with unprecedented opportunities. He entered into what the German scholar Hans-Walter Schmuhl has described as a “Faustian Pact,” whereby his Institute provided scientific legitimacy to Nazi policy and in return attained unlimited power and access to the highest echelons of the Nazi State. Medical scientists and doctors were virtual demigods during the Third Reich. Their expertise was seen to hold the key to creating the modern eugenicist state desired by Hitler and the Nazi Party. Throughout his career, Fischer drew on his Rehoboth Baster research to boost his status as the leading scientist on eugenics and racially mixed populations (Mischlinge). The same ideas about racial mixing and “bad blood” that were derived from Fischer’s Rehoboth study later came to haunt Jews in Nazi Europe. Both marginalized and liminal groups – the Basters and the Jews – became victims of scientific ideas that were incubated in the colonies.

The German Jewish political theorist Hannah Arendt once used the metaphor of the boomerang to account for how colonial violence bounced back to the heart of Europe. Arendt was referring here to cases such as the Herero and Nama genocide in German South West Africa from 1904 to 1908, which boomeranged back to the heart of Europe with devastating effect only a few decades later. But what Arendt didn’t look at was the way in which the colonies became laboratories for racial science that later came to haunt Europe.

In the winter of February 2013, the filmmaker Mark Kaplan and I did an interview in Berlin with Hans-Walter Schmuhl, the leading German scholar on science in the Third Reich era. On a bitterly cold winter’s morning we met at the Institute, which is now the Department of Political Science of Berlin’s Free University. Schmuhl’s many years of research into Fischer’s directorship of the Institute from 1927 to 1942 had sensitised him to the dangerous conceits of the scientific enterprise. He had tracked how scientific ethics in Nazi Germany were violated from the start. In the beginning the research was done without consent of subjects in mental asylums and prisons where inmates were compelled to participate. By the time the war started research was taking place in more extreme settings, including prisoner of war camps, culminating in Mengele’s studies in the twin laboratories of Auschwitz. In the name of social improvement, an international eugenics movement had unleashed a scientific monstrosity that underwrote Nazi ideology and policy.

During the early decades of the twentieth century, eugenics science was embraced by political groupings from across the entire political spectrum. It was an internationally respectable scientific programme that sought to improve the health of national populations. Eugenics activists in the United States were particularly effective in lobbying and influencing US sterilization and immigration policies.

US scientists were leaders in eugenics and the Germans found themselves playing catch up. During the late 1920s, Fischer’s Institute received generous funding from prestigious institutions such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Institute. Fischer’s Institute was discredited after the Second World War, but Fischer and most of his researchers came out relatively unscathed by the de-Nazification process. In fact, their studies were cited well into the 1960s.

Finding Fischer’s imprint at the museum at Stellenbosch University raised a number of questions for my colleagues in the anthropology section of our Department. What were these objects used for and what scientific paradigms existed at the time they were used? It is widely known that Verwoerd and Eiselen, the two chief architects of Apartheid, taught at Stellenbosch University. But it is widely believed that they were more interested in cultural and ethnic difference than racial science or eugenics. At the time my colleagues and I wanted to know what a skull and these hair and eye colour charts were doing in the Volkekunde Department, and what did this tell us about history of the human sciences at the university? These questions also convinced my colleague, and student assistant at the time, Dr. Handri Walters, to begin her doctoral research on the historical intersections of race, science and politics at Stellenbosch University.

These questions also served as a catalyst for a research project in my Department that sought to investigate what kind of social science was taught at Stellenbosch at different historical periods of the past century as well as broader contemporary questions relating to science and ethics. The history of transgressions of ethics perpetrated by German scientists during the Nazi era should also make us wary of current developments in scientific fields such as genomics and race-based medicine. It would seem that scientists everywhere prefer to push the boundaries of their disciplines rather than engage in abstract philosophical debates about ethics. Finding Fischer’s imprint at Stellenbosch University suggested that his brand of racial science was global and, at the time, represented international “best practice.” Given what we now know, we need to ensure that we rigorously engage with the ethical challenges posed by cutting edge contemporary science such as genomics.

In April 2019, a controversy exploded at Stellenbosch University following media reporting of a social science study that claimed to have found that ‘Coloured’ women had an increased risk for low cognitive functioning due to low education levels and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours. The study, entitled “Age and education effects on cognitive functioning in coloured South African women,” was done by researchers from the university’s Department of Sport Science. It involved a group of 60 women (18-64 years) and, on the basis of this small sample, made generalisations about the cognitive ability of ‘Coloured women.’ In the midst of the controversy surrounding the study, Stellenbosch University’s Professor Aslam Fataar made a statement on behalf of a group of academics in which he declared:

“We decry the continuation of colonial and apartheid research thinking that makes essentialist connections between race and ethnicity and particular attributes or aptitudes of a group of people. Such use implicates the institutional culture, policies and strategies of our university.”[3]VOCFM

Clearly, the legacies of the devastating histories of racial science and eugenics during colonialism, the Holocaust and apartheid are not yet over.

| 1. | ↑ | Steven Robins, Letters of Stone: From Nazi Germany to South Africa (Cape Town: Penguin Random House Publishers South Africa 2016) |

| 2. | ↑ | Rhineland Bastard (German: Rheinlandbastard) was a derogatory and racist term used in Nazi Germany to describe Afro-Germans, believed fathered by French Army personnel of African descent who were stationed in the Rhineland during its occupation by France after World War I. There is evidence that other Afro-Germans, born from unions between German men and African women in former German colonies in Africa, were also referred to as Rheinlandbastarde. |

| 3. | ↑ | VOCFM |